This article throws light upon the top nine examples on successful advertising strategy. The examples are: 1. VDIS-97 Black into White 2. Hcl Copiers 3. Kinetic Honda 4. Bagpiper Whisky 5. Gold Riband Whisky 6. Thirty Plus 7. Gold Flake 8. Hero Honda 9. Captain Cook Atta.

Example # 1. VDIS-97 Black into White:

The Government played the role of the marketer and whipped up Rs. 10,050 crores as tax through VDIS-97. With some fine strategy and creative behind the job, the six month extensive advertising was effective and provoking and yielded immediate result and advertising created an exciting new brand with tremendous success.

The use of communication to live people out of the closet with their income shows how potent advertising can be to address a host of public concerns. The success of VDIS-97 indicated to the government the ways of gaining popular awareness and acceptance for its reform strategy.

Before VDIS many such schemes were floated by many Governments time to time but they failed because the successive Governments failed to articulate clearly how the economic reforms with benefit the common man.

For advertising about VDIS-97, finance ministry hired Hindustan Thompson Associates (HTA) and Ogilvy and Mather (O & M). For selecting the advertising agency, finance ministry invited nine ad agencies for strategy presentation within 15 minute time with the objective of “Getting people declare their incomes under the scheme”.

Both HTA & O & M happened to made presentations along similar lines then the finance ministry enquired that whether can they work together as the account. Both HTA & O & M accepted the offer jointly and it was first time in the world that the two advertising agencies were working on an account jointly. The core team was constituted of ten executives- five from each agency.

The broad objective of the campaign was “to propagate the culture of tax compliance,” and the subsidiary objectives were:

Objectives:

1. Asking people to file their returns even if they don’t come under the taxable income bracket

2. To relate paying tax with pride as being an ideal citizen

3. To encourage the people to declare their black money and making it white by paying 30% tax.

The advertising budget for promoting this scheme was set as 30 crores by central Board of direct taxes (CBDT).

While the CBDT brief was that communications should address the people who did not but ought to pay taxes, the agencies wondered if reach beyond urban areas would translate into disclosure. It was hard to sharply define the target audience since the disclosure. It was hard to sharply define the target audience since the number of people evading taxes is large and come in many occupation and sizes.

As neither CBDT nor the advertising agencies hired were having the experience of promoting such type of scheme, everything was started as fresh and a lot of brainstorming was done. It was decided that branding must be done and name VDIS should be popularized by saying as “VDIS stands not just for another amnesty scheme but a whole lot of other things besides”.

The agencies suggested to the government cannot and stick approach. First wooving the person to declare their upto undeclared incomes and in the later stages with the fear appeal to pay taxes.

Strategy:

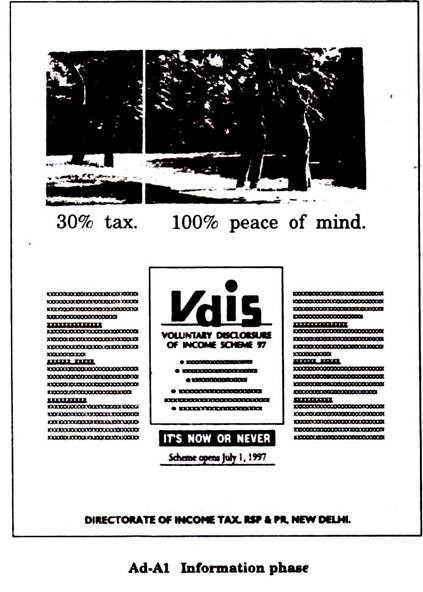

The campaign proceeded in four phases in six months:

Phase-I — Information phases-45 days

Phase-II — Breaking barriers phase-60 days

Phase-Ill — Consolidation phase-45 days

Phase-IV — Count down phase-31 days

Phase-I—Information Phase:

The scheme was launched on July 1, 1997 with the multimedia campaign and the ads were kept simple. Mainly they highlighted the VDIS scheme as such and the basic facts about the amnesty scheme and the other things for example ‘Did you know that VDIS-97 is also open to those covered under section 139’ (Ad-A1, A2, A3, A4).

Phase-II—Breaking Barriers Phase:

The finance ministry was not clear about the number of people in different categories who were either paying or evading tax in this stage six segments were identified as traders, small businessmen, property developers, jewelers, brokers and self-employed, executives. This phase dealt with tax compliance barrier and conveyed the point of view of tax evader and knocking down the argument as excuses.

TV was used as the major media for this phase with the objective of creating family pressure on the evader. (Ad B). There were also some print ads with the theme “Why should I give the government my hard earned?” I am not sure that my tax money will be used for. So why should I pay it?”

Phase-III—Consolidation Phase:

This phase started with the simple persuasive argument that if one pay 30% tax. The rest of the money can be used productively. It state also what the government will do with the VDIS 97 tax money (Ad CI).

The communication stressed that paying up would allow a tax payer to Haunt his wealth with pride, without fear of the tax man and negative appeal was used. (Ad C2, C3, C4) One head line was ‘The more homes I buy, the less sleep I get’.’

Towards the close of the campaign celebrities are Kapil Dev, Mithun Chakravorty, Amjad Ali Khan and Kamal Hassan were used as celebrity endorsement.

The message was a show that earning money didn’t imply that evasion had to follow with little fear appeal. (Ad C5) (Mithun . . don’t you dare tell me black money is necessary to do business … I used to sleep on pavements . . . today I’m the country’s highest income tax payer . . .”)

Phase-IV—Count Down Phase:

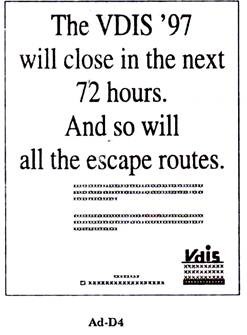

This phase started from Dec 1, 1997. A total fear he was created with the slogan “It is now … or never”. Last 31 days to choose between 30% tax and 300% penalty.”30 days to make money more productive and so on (Ad D1, D2, D3, D4).

Every day the days left were written to highlight the importance and to increase the fear appeal. Mean while raids were carried out on some brokers in Bombay and traders who handle hundi transactions and bullion. As the menace heightened, the tickle of people heading towards income tax offices turned into flood.

Outcome:

In comparison with the earlier schemes, VDIS 97 proved for more effective. In the past well to do Indians were reluctant to come clean because the tax rates were high. The slashing of individual income tax rate to maximum of 30% and corporate tax 35% made declaration more attractive than ever. For many, tax evasion was no larger worthwhile: for concealing income has its cost too.

The dropping of tax levels—the carrot had been accompanied the stick—to file the return who fulfills any two of these criteria as owned either a house or a car, had a telephone connection or had travelled abroad. The ground had been prepared before VDIS was formally launched. VDIS was different in that it decimalized the process of tax evaders emerging into the open.

In the past people were having inhibitions about coming forward and declaring their incomes because they were looked down upon. For the success of VDIS 97 scheme, the public relation ground was prepared. The main thing was to remove the adverbial relationship between assesse and income tax officer.

For this scheme the people at the counter were trained to deal, the people politely as soon as the declarant lands the counter. It was made sure that to build. The greater confidence among the people, the certificates of declaration are to be issued without any delay.

On the marketing (of scheme) side, the advertising efforts were supplemented with a high degree of interaction with professional groups, business chambers and others. A direct contact programme to reach out to the influencers—Chartered Accountants was carried out. Besides that all the top revenue officials toured extensively convincing. These influencers to cooperate.

The Lesson:

The success of VDIS 97 set an example of synergy between the Government and the private agencies and it worked wonderfully. The other message was that professional advertising can work wonders in the most unexpected situations. It might persuade Governments to use advertising more in public interest.

The success of VDIS 97 have done extensively good for the reputation of Indian advertising. With the success of the scheme, ‘ADVERTISING WORKS’ would be written in larger point size and in-front of a larger audience than perhaps even before.

Example # 2. Hcl Copiers:

The story began in 1984 when Hindustan Reprographics Limited (HRL) a sister concern of HCL launched the plain photocopier with the brand name ‘Finesse’, the company had a tie up with Toshiba. Though several brands were available to the consumer, HRL quickly emerged as the leader in the business, primarily on account of its superior direct selling capabilities.

In the year 1986-87, the production suffered in the process of indigenisation and this made its impact on the penetration of the brand. HRL merged and became the division of HCL.

As HCL objective for computers was set on the higher side, the resources where diverted to that division and Finesse thus received the set back. Modi Xerox seized the opportunity and soon became the market leader. HCL made small gains by adding two more models.

In 1988, in the course of a customer care programme launched by HCL. The programme, among other things, made it attractive for consumer to buy more than one product from HCL range— say PC-AT and EPABX system.

An analysis of results revealed that awareness of HCL copiers even among the company customer base was abysmally low. Prospects responded and considered every other HCL product but when it came to copiers only Modi Xerox was considered.

In Oct., 1988, the company decided to come back with the expanded product range, strengthened and revamped sales infrastructure. ‘Finesse 121’ was launched with the price Rs. 45,000 lower than the modi Xerox. The machine was ideal for those who sought a reliable copier but found current prices unaffordable.

After sometime, Finesse 1025 was launched. To this product mix was added Risograph, a product designed for high volume heavy duty applications. It was the latest machine international incorporating sophisticated electronics. It could copy on the cheapest of paper at speed of copy every half second.

With the new product in place and the sales team ready, the problem was that of advertising. Since product, management had designed the product mix to address each market segment specifically, the biggest temptation was to follow suit with advertising.

The considerations were as follows:

1. Pre-October, the average monthly sale was around 75 machine. Though HCL was a statistical No 2, the gulf between it and modi Xerox was huge. Modi Xerox held an estimated 45 per cent of the market.

2. Specific models came into the picture only when the consumer is evaluating his options. One problem was that HCL was not even on the consideration list.

3. Advertising does not sell office automation products. Salesmen do. Advertising’s main task in this product market is to open a dialogue between the advertiser and the prospect.

4. When a manager buys office automation products, the process is different from his buying durables at home.

In the case of office automation, he is in effect making a business deal. He not only has to evaluate brands rationally but also has to be seen to be doing so. In this product market, therefore, it is the price performance ratio that determines brand choice.

The strategy was as follows:

After receiving these considerations, the outline for a campaign to re-launch the brand emerged. Firstly, the brand had to be established before tackling each model’s specific market segment. Although Finesse was the brand name, it was popularly known as the HCL copier as the HCL was having a brand equity.

The most compelling argument in favour of modi Xerox positioning was superior price performance story. This was a consistent advantage across the entire range of HCL copiers and could be demonstrated, because of HCL image “cheaper than Modi Xerox” would not mean the inferior product in the consumer mind. That’s why HCL photocopier was positioned the brand as better copiers because they offer better price performance.

The objective of advertising was not to over take modi xerox. The task was set to quickly ensure that whenever prospects invited modi xerox, they also call HCL in. Until the campaign, in the consumer mind, it was a care of modi xerox and the rest. The advertising had to convert that of Modi Xerox, HCL and the rest. A comparative advertising was used.

Subsequently the question of why Modi Xerox was named in the advertising often came up. The reason was that failure to name the prime competitor while making comparative price performance statements would have diluted the impact of the claim as also taken away from its credibility. It would have made the claim much more diffident and tentative.

At the same time to deal with the response of comparative advertising a second layer of less skilled sales personnel was created. This force was expected to contact the potential buyer within 48 hours of the first inquiry being made. After assessing the situation, they were than expected to get a more senior sales person in on the job.

The result of the campaign at the end of financial year 1989 was:

(a) HCL sold several fold more copiers in 1988-89 than the preceding year.

(b) The copier slot in the consumer mind is no longer filled by Modi Xerox alone.

Example # 3. Kinetic Honda:

Kinetic Honda Motors Ltd was incorporated in February 1984 as a joint venture between the Pune based kinetic engineering ltd. and Honda Motor Company of Japan. In April 1986, the first batch of 100 cc Kinetic Honda scooters rolled out from its factory at Pirmpura in Madhya Pradesh on to Indian Roads.

In the first year, Kinetic Honda sold 11,000 pieces against the country wide scooter sales of 5.25 lakh, a market share of 2.1 per cent. In ‘1986’, Bajaj Auto Ltd. and its subsidiary , Maharashtra Scooters Ltd, employed the lion’s share of the Indian scooter market selling around 3.8 lakh scooters or 73 per cent of the market.

Their nearest competitor, Lohia Machines Ltd. (LML) 21 per cent, with sales of 1.09 lakh scooters. Other scooter manufacturers had minimal presence and almost all models were similar in characteristics and design.

The Kinetic Honda, however, was a unique scooter in many respects with certain advanced features that made it some what ahead of its times. It had an electronic start facility, which meant it could be started with the flick of button, with no kick required.

It also had variomatic transmission and automatic gear shifting, an automatic chocke, built in indicators (In 1986, not all Indian scooters came with indicators) and a new wind tested streamlined design. The body was of reinforced plastic in bright colours. The company expected the features to sweep Indian consumers off their feet, and give a serious run for their money to Bajaj and LML. But this was not to be.

Soon after the launch, Kinetic Honda started facing a severe problem of acceptance. Post introduction market research brought to light the fact that the Indian psyche was not geared towards technical advancement (at least at that time). People preferred to stick to familiar models, even if they were out dated and comparison with the market leader was inevitable.

Ironically, the advanced features were working against it. Its use of reinforced plastic and its sleek compactness led to the misconception that it was light and flimsy, as compared to the solid, weighty look of the other scooters. Also since it was a 100 cc scooter, people thought it was not as powerful as the 150 cc Bajaj scooter.

The Electronic start also worked against the product. The kick start, it was discovered, had deep psychologically pleasurable associations, and the electronic start was not considered to be an improvement. This feature, along with the variomatic transmission in fact branded the product as a “ladies scooter”.

The bright colours detracted from the seriousness of the product in the perception of people and on the whole it was not viewed as tough or rugged enough for Indian roads.

The only solution was to first educate the customer about the various features of the Kinetic Honda Advertising repeatedly addressed the various consumer misperceptions. The marketing team held a number of live demonstrations at public places to remove misconceptions. For example, magnets were used to demonstrate that the scooter actually had a steel chassis beneath the plastic body.

IN 1988 came a stroke of luck which the company capitalized on heavily for promotion. Alpha Motor Co, a Bombay automobile testing firm, conducted a test of scooters called the Alpha Lap of India. It was the toughest test of scooter ever carried out in the country.

In a closely monitored route of over 20,000 km of extremely hostile terrain a Kinetic Honda was pitted against two 150 cc scooters; a Bajaj and an LML Vespa NV. The Kinetic Honda was judged the best scooter over all, and the company carried out a massive advertising blitz highlighting this fact all across the country.

The Alpha Lap victory was the best thing that could have happened to the scooter. It was conveniently compressed the time frame necessary for a new scooter to prove its durability by putting the machine, in a few days, through Massine stress comparable to what it might under go normally over years. Soon after, Kinetic Honda sales jumped appreciably.

Subsequently, the scooter was entered in a series of monsoon rallies organised by a Bombay racing organisation, sports crafters (every year during the rains). Kinetic Honda emerged victorious thrice in these rallies carried out on sand, morsh and slippery flats.

In 1989 a series of ads were run with the head line “did you know”? The customer was told that Kinetic Honda offered more power per cc than any other scooter, it was much tougher and heavier than it appeared; it had cleared the specifications of the Motor Vehicle, Act1988 with flying colours and it was the only scooter to offer an unlimited mileage guarantee. Mean-while the company continued its efforts to establish the product as the most rugged scooter on Indian roads.

In October 1989, a young couple from Mysore, Mr and Mrs. Yoganand, under took an expedition to the Khardungla Pass, the highest motorable road in the world, on a Kinetic Honda .It was the first time that a scooter had ever achieved such a feat and it was entered in the Guinness book of records. The company built on this the following year by sponsoring a serial on the Guinness records on Doordarshan’s national network.

The scooter made it to the Guinness book a second time in 1990, when it organised an event of 1 001 hours of continuous riding at the sarasbaug Traffic Park in Pune. The rationale behind this even was to establish the scooter as a reliable one in the north Indian market.

The product has hardly made a dert in the very large two wheeler market of the north Research showed that reliability was the principal consumer concern in this market as distance covered were large and the small local mechanics were equipped to handle a sophisticated scooter like Kinetic Honda.

Kinetic Honda spare parts also came at much higher prices than the Bajaj ones. However, the low rate of break downs and replacements of parts, the company hoped, would compensate in a large way for this perceived disadvantage.

Thus three drivers from Delhi were selected to shatter the earlier world record (held by a 500 cc motorcycle in Italy for 560 hours of continuous driving) on May 17, 1990 and set a new record of 1.001 hours. The riders undertook a heavily publicized victory tour on the record breaking scooter starting from Delhi and ending at Pune.

The company also started two clubs. The idea was to tap a powerful channel of advertising the word of mouth of satisfied users. One was the founder’s club, where any owner of a Kinetic Honda could become a member and avail of the use of another Kinetic Honda in any Indian city where he travelled.

The other was called the mountain adventure club which offered Kinetic Honda on hire at hill resorts. The performance of the scooter on these steep climbs, the marketing team figured out would convince even the biggest sceptics.

As sales have increased, a typical kinetic Honda customer has emerged. The company describes him as “one who is or is on the path to being a social some body”. Though initially a majority of the customers were in the age group of 25 to 35, today the range has broadened to 18-60 years. Most Kinetic Honda customers fall in the Rs. 2,500 + monthly house hold income category.

The company would like to believe that its customers “are different from those of Bajaj and LML in that they are upwardly mobile, quality conscious and not willing to settle for less than the best”. The company slots it scooter today as a product which is not just value for money, but premium value for money.

In 1991-92, Kinetic Honda was the only scooter company to have registered a sales growth of around 14 per cent, while all others have registered negative growth due to the industry wide recession.

The product has increased its market share to 11 per cent and wiped out the looses accumulated over the initial years. Export volumes have jumped over 100 per cent with countries like Cyprus, Mauritius, Macau, Dubai and Greece among its foreign markets. In a recent drive to gain international recognition, the company sponsored operation Sahara attack where six Indians crossed the Sahara desert on Kinetic Hondas in 18 days. It was first time that a scooter had crossed the Sahara.

Today, Kinetic Honda ads carry a base line which says:

The future belongs to us. The product now seems much more in tune with the times than when it started off.

Example # 4. Bagpiper Whisky:

The Bagpiper liquor the UB group brand was launched in 1976. Liguor category have a tremendous restriction on advertising and distribution. Advertising is not allowed and only licensed shops could sell liquor. Black Knight, one of the leading whisky brands from Mohan Meakin, used to work on a shortage situation and rationed itself. On the other hand, new comers had a tough time.

Marketers relied on push because pull for a brand could not be created through advertising. To get a distributor to stock a new brand was a major task. He had to be cajoled and convinced with discounts. If one refused to stock a new brand, others followed suit and the brand didn’t stand a chance.

The entire marketing exercise concentrated on getting the product on to the distributor shelves. Most companies just went along with the prevailing state of affairs rather than break new ground through innovative strategies.

They paid lip service to promotion in terms of POPs, depicting women en dishabille, or badly produced playing cards, ashtrays, glasses, trays,’ decanters, ice pails to be given away as gifts, follow ups at retail level, creating consumer awareness for the brand, building its equity were all alien concepts.

Bagpiper entered the fray with the intention of becoming a brand rather than being just another whisky. To date, the company defines its market as the evening entertainment segment.

The leading companies at this point were Mohan Meakin (Black Knight), shaw Wallace (Old Tavern) Jagjit industries (Aristrocrat), khoday (Peter Scot, Democrat) and MC Dowell (NO. 1 Diplomat). Herbertsons, edge was a better market on orientation. It had been in the market since 1913, selling consumer product.

In the 80s, Bagpiper used a number of marketing tactics, did a lot to change the rules of the liquor market. The brand had to create consumer pull to reduce dependence on the distributor, but was not allowed to advertise. Herbertsons found the solution in sports.

In the early ’80’ one day cricket was rapidly growing in popularity. By sponsoring several one day matches, with the bagpiper man of the match award, man of the series award, the Bagpiper trophy and so on, the brand had its first taste of mass exposure. Without knowing it, Bagpiper had set the ball rolling for the currently massive business of event marketing.

The cricket sponsorships boosted brand sales considerably. Bagpiper began sponsoring major hockey and football matches, horse races and other sporting events. Even today, Herbetsons sponsor some football tournaments in Calcutta.

In 1985-86, Doordarshan decreed that if the sponsor was a liquor company, its name could not be flashed on the TV screen. Besides, the camera was not to focus on hoarding of liquor products inside the stadium. It was back to square one for Bagpiper. It had been able to build a certain amount of brand equity, and now had to find other ways to take it further.

Herbertsons found the perfect solution. In 1981, the company had launched playing cards, dacanters and other items with the same brand name as their liquor brands. It now decided to launch a club soda and extend the Bagpiper brand equity to this product.

Advertising whisky, was banned but not advertising a product of the same name as that of the whisky. Every time the club soda was advertised, it had a rub-off effect on the whisky. This has since then become the staple of every liquor communication exercise in India.

To give the brand a contemporary but lasting personality, it chose film stars with an enduring appeal to endorse Bagpiper Club Soda. In the early 80s, it was Ashok Kumar, followed by Sanjeev Kumar and Pran. In 1987, Shatrughan Sinha and Jackie Shroff were added to the list and lately, Dharmendra.

The campaign continues with no change in layout and execution, except for the incorporation of new film stars to maintain consistency yet prevent the brand personality from getting jaded. The line “the makings of a great evening” was born. The base line “A legend comes alive” has been retained from the very beginning.

As a follow up, audio cassettes of songs in different moods-romantic, sad, fun – picturised on the endorsing stars were given as gifts. In 1988-89, the Bagpiper silver screen contest was launched. The centerfold in movie magazine was sponsored and the star featured every month was called the movie Bagpiper discovery of the month.

This strategy of identifying Bagpiper with stars has remained consistent over the decade. And it is common to all the elements of Bagpiper’s marketing and its biggest edge over its competitors in having consistent communication.

Diplomat, faced with falling sales, changed its colour from clear to green and then again to clear. Other brands have also changed their base line labels and other aspects of their communication from to time. Bagpiper’s communication and brand offering have remained consistent over the years.

Another area of brand promotion in liquor is that of consumer gifts which carry the brand name. But by and large, most of the gifts were shoddily produced, with graphics, colours and shapes which had no connection with the image or look of the brand.

In another first, Herbertsons saw to it that the gifts it gave to consumers were in black and gold with the Bagpiper name on them, and were of excellent quality, the whole idea being to align the gift with the brand image.

Example # 5. Gold Riband Whisky:

The 114 year old PNCL has a balanced portfolio of products. Its presence was strongest in white spirit segment, which is made up primarily of gin, vodka and white rum. Although PNCL’S Blue Riband dominated this segment with as estimated 63 per cent share of the premium gin market, the white spirit segment made up only 4 per cent of the Rs. 722 crore (in 1989-90) IMFL (Indian made foreign Liquor) market.

While the company was growing quickly, it was becoming evident that to enter the big league, it would have to enter the whisky market, which makes up 63 per cent of total IMFL sales by volume. More specifically, PNCL was keen to enter the “regular” or “popular” segment which makes up 40 percent of the whisky market.

In 1990, for instance, the regular whisky segment, defined broadly as brands whose 750 ml. bottle was priced at between Rs.80 and Rs. 95 (at retail level) was worth 80 lakh cases (12 bottles to case).

PNCL knew from it experience with Royal Reserve, a brand that was performing indifferently, that the regular whisky segment was among the hardest to crack.

All the big boys have a presence in this segment with some really strong brands: Bagpiper, the largest of them from Herbertsons; Diplomat from MC Dowell; Aristocrat from Jagatjit; Directors special from Shaw Wallace; and the largest entrant, Officer’s Choice from Cruick Shank. All these brands sell around one million cases or more per year.

There are only 16,000 odd liquor out lets across the country. And it is these retailers who decide the fate of any brand. The business therefore is more sales and distribution oriented rather than marketing oriented. In any other product category, a marketer could get around this problem by creating a strong consumer pull for his brand.

That isn’t easily possible in liquor because of the restrictions ,on advertising. Worse still, for the new entrant, it is difficult to place his bets on product difference since the technology involved isn’t particularly high. Lastly, consumers generally show evidence of cluster loyalty—if one brand is unavailable, the buyer will probably settle for another brand with in a cluster of name acceptable to him.

The PNCL management felt that most Indian drinkers, while apparently satisfied with existing brands, were nevertheless apprehensive about a hangover.

Could a new brand offer a benefit which consumers wanted but which was not being offered by existing brands? (In fact, advertising for hard liquor is imaged based, and offering a consumer benefit is virtually unheard of). A market research agency was assigned the task of checking out whether.

1. There was a need felt for a whisky brand with a low hang over;

2. This need was being met by any of the existing brands in the regular segment;

3. There was credibility in the claim of low hang over for a brand selling at only Rs. 90 (750 ml.).

The target segment was identified as: male, 25-46 years, with a house hold income of Rs. 2,5000-3,5000—middle to lower level executives plus self-employed businessmen.

What PNCL needed was a name and packaging that would can note premiumness, arrest attention, and existing liquor communication showed that nearly all of it had some common elements; Party/group situations; women in various states of undress; a glass containing liquor; Trays containing snacks like cashew and chicken; lastly, the situation depicted was in variably indoor, and normally captured an evening. The big idea was to change the rules of liquor communication by shifting the venue from indoor to outdoor, from evening to morning, and from darkness to light (freshness).

The next issue that needed settling was the route to be adopted for the creative execution. The options were:

1. Aspirational route:

A young couple jogging early in the morning in a park, along with their dog.

2. Problem solving route:

Slice of life visual showing the Gold Riband man getting into his maruti the morning after, on his way to work while his wife happily waves to him. The feeling was that the typical consumer of Gold Riband, a middle to lower level executive, might find it difficult to emphasize with the aspiration route.

On the other hand, while the problem—solution approach would be easily understood, could capture the consumer’s imagination.

Faced with this dilemma, PNCL decided to test the two communication options with matched samples of regular whisky drinkers. It helped in deciding in favour of the first option because it clearly conveyed a single key benefit—freshness the morning after. On the other hand, the problem solution communication conveyed a bunch of benefits.

Gold Riband was launched on September 17-1991 and a number of unusual promotional efforts followed. It was introduced in a faced manner and within just the first consumer resistance to a new brand and encourage trial.

An obvious name presented itself: the ‘Riband’ of blue Ribonds. On the minus side, the argument was that if the new whisky brand failed, It could have back lash on blue blue Riband. More specifically, the feeling was that the word ‘Riband’ was associated with white spirit and might not be easily acceptable to the whisky drink. But research was reassuring: Ribond was associated more with quality rather than white spirit.

On the plus side, ‘Riband’ was readymade property which had both consumer and trade acceptance. Experience proved that in the Indian Made Foreign Liquor (IMFL) business, where failure rates are exceptionally high, nearly all recent successes had been cases of line extention. What word should precede Riband?

Royal, premium or Gold?

1. Royal Ribond was rejected since PNCL already had Royal Reserve in the same whisky segment.

2. Premium Riband got the thumbs down because the word ‘premium’ in India represents a whisky category which includes Peter Scot, Vintage and Royal Challenge. It would have raised consumer’s expectations far too much.

3. Gold Riband got the nod because it was easily pronounceable and while promising a superior blend, would raise expectations only to the point to which they could be fulfilled.

PNCL briefed its advertising agency (Oglivy and Mather). The communication objective:

Gold Ribond is a premium whisky which offers freshness in a memorable manner. The task was to convert the negative—low hang over – into a positive statement of benefit. This was done very well by coining the head line. “Good mornings after great evenings”.

As for the visual, an evaluation of five moths of its launch in various states, It notched up sales of over 1,00,000 cases. By the end of the first 12 months more than 3,00,000 cases are expected to have been sold. This must undoubtedly be some kind of a record of performance of a new whisky brand.

Example # 6. Thirty Plus:

Ajanta Pharma was set up originally as a small packaging unit in Aurangabad. In 1973, it started manufacturing and marketing its own products.

By the late 80’s it had build up a strong presence in rural markets of Gujarat and Maharashtra with brands like Pinkoo gripe water, Apttol antiseptic, Apcose-D glucose power and Trimol analgesic. In 1989, company decided to go national in the over the country (OTC) pharmaceutical segment with the Ginseng based product.

Creative unit was asked to develop the product concept from brand name to packaging, including suggesting of a launch strategy. The agency carried out an in-depth study of the properties and pharmacological effects of the properties and Ginseng.

It was found that it could be used as an aid or curative agent for an enormous variety of maladies like liver damage, diabetes, blood pressure, stress; it also reduced fatigue, prevented premature aging, and helped the digestive and circulatory systems. However, as OTC product, only the general energizing qualities could be activity stressed.

The study also gave an indication of who the consumer was likely to be; mainly people above 40 years. It is at this age that an individual feels the maximum stress-physical, psychological, social and even economic-due to the product should address itself to these problems – offering relief from stress and fatigue and thus helping the user to live a successful life.

Although women too are subject to stress, it was felt that segmenting career oriented males would help give the product a sharp focus.

Consumer research was initiated to help define the general perception of middle age and its related problems. Men in their 30s, 40s, and 50s were interviewed. It was found that mid – life crisis was experienced only after the age of 40. It was only after a hectic period of career consolidation and settling down in terms of family and social life, that a man felt that the best part of his life was over.

All the other ginseng brands promoted ethically, were well accepted by the medical profession and enjoyed good market shares. For Ajanta Pharma’s product to succeed in the OTC market, it was felt just generic awareness of ginseng was not enough. A product plus was needed.

Ashwagandha, a well – known Indian herb used as a restorative and tonic, was added to the formula lotion. It was felt that its presence would immediately convey energising power to the Indian consumer. The combination decided upon was 500 mg. of Korean ginseng and 500 mg. of Ashwagandha.

The next step was to give the product a name that would personify the product promise. The fact that it would be viewed as a health supplement, was taken into consideration. Competition could be expected from a wide variety of brands, many of them not related to ginseng at all like Tonos 7, (Seven) Chyawan Prash, Vita ex, Shilajit Surbex T, and even Horlicks and Complan.

The brand name had to identify the product as number of products already. The person was to instead build up a certain atmosphere of confidence and success.

Names like Dhirubhai Ambani, Kabir Bedi, Jahangir Khan, Sunil Gavaskar and Jeetendra were considered. They had all reached the peak of their carriers and were looking forward to even greater heights. Jeetendra, the ‘every-green Hero’, was high on the list. His fit and youthful appearance was a visible statement of the advertising message.

Rs. 1.8 crore was spent on advertising in the first year. The brand was launched nationally in January 1990. The capsules came in blister packs of 10, put in a box, to be slipped into one’s pocket or briefcase conveniently. The red and gold packaging sought to convey exclusively and richness. The plus symbol in the logo reaffirmed the pharmaceutical image as well as the positive product benefits.

Thirty Plus made available in about 30,000 A-Class chemist outlets all over India. Down the line availability was also ensured among smaller chemists. Recognising the influence of the chemist in the purchase decision the company carried out product detailing exercises for the vendors.

Success came quickly. Tracking studies a year after the launch showed a 70 per cent awareness level. However, the high pricing restricted penetration of the brand to cost – conscious buyers. Consumer research, a year after its launch, showed it as energiser without confusing it with existing product, and generic brands.

It also had to have top – of – the – mind recall. Several alternatives were tested for acceptance among consumers juvenal, elix, invigora, Augmentin and thirty plus oriental sounding names, like Yuvan and Yangan, were also tested.

Thirty plus aroused maximum interest among respondents, who admitted that they felt good asking for a product that measured them they were only over 30. No one would have reacted to forty plus or fifty plus positively. Pre-launch research revealed that a majority of the respondents were reasonably satisfied with their home life and carriers. Few took any tonic regularly. A common reaction was “I don’t need a tonic”.

A totally new creative strategy had to built up to create the need for an energy restorer. Direct appeals to feelings of tiredness and weakness would quite possibly evoke a defensive reaction or outright rejection. It was thus decided to focus on the more positive aspects of middle age, emphasising a settled and optimistic future ahead.

Advertising was aimed at reinforcing feelings of confidence and optimism. Thus the line “the best has just begun” developed and thirty plus was offered to individuals over 30 with ‘the power to go’. Quite early in the planning stage the question whether a celebrity could be used to promote the product was discussed.

Direct endorsement by the celebrity, it was felt, might reduce credibility as there were umpteen film stars and cricket players pushing the product. Research showed the existence of a segment of ‘aware non-users’ who shied away from the product simply because of its price. This finding led to a line extension in August this year in the form of Thirty Plus blue.

The costly ginseng component was reduced to 250 mg, while the ashwagandha content remained the same, and the new product was priced at Rs. 39.90 as against the price of Rs. 69.90 for the red variety. The market for Ginseng products is estimated at Rs. 14 crore. Sales figures for thirty plus red crossed Rs. 5 crore, a market share of 37.3 per cent-by the end of 1990. Thirty plus Blue is expected to raise the market share further.

Example # 7. Gold Flake:

India’s per capita consumption of cigarettes is 101 sticks per year and 8 billion sticks per month and it is 10% of world’s consumption. In India one interesting feature of smoking is that youth between the age of 15-35 smoke much heavily than the older persons. Gold Flake, the ITC brand is most popular and perceived very stylish and give status symbol.

Gold Flake was launched in 1915 by the then Imperial Tobacco company (which became Indian Tobacco Co. later and then ITC) was a filter less cigarette and it was premium priced and most expensive cigarette brand at that time. By 1950’s the brand was promoted as creating exclusivity of the brand by creating image of the heritage consciously smoker who believed in the promise of quality with the ad-line ‘where ever you go, there’re good’.

By 1960’s the filter tipped cigarettes gained acceptance among masses and ITC gave another brand wills navy cut to this segment in 1963. In 1970 ITC lunched gold flake filter Kings in yellow and red pack with the logo ‘Honey dew’ Written on the underside of the oval. Though the company said that it is a blend (tobacco sweetened with molasses), many believed that it is a brilliant subliminal message, if read fast, ‘I need you’.

Gold Flake Plain cigarettes was repositioned as the best plain cigarette you can buy as the advertising emphasized on quality. But after sometime the sale of Gold Flake plain started declining and ITC reduced its pack price from Rs.1.25 to Rs.1 for 10.

As the previously positioning Gold Flake, the brand was promoted and for those customers who value exclusivity, heritage and product quality. The new attribute now was added as length with the slogan worth its length in gold and gold flake brand was portrayed as the brand to smoke for people mooring in the right social circles. The ad thus began showing two couples in a social setting, which continues as the brand’s integral slice of the life theme. The campaign broke in August 1970.

The late 70 and early 80’s witnessed some key changes into the consumer’s attitude as being exposed to the more carefree and westernized life style and the gold flake’s traditional positioning as Indian life style palling. At the same time Godfrey Phillips Four Square Kings was positioned on westernized life style with bright out door visuals of adventure sports urging the consumers to live life king size.

Four Square King size was cheaper than Gold Flake but at the same time Gold Flake Filter Kings maintained its customers as the Four Square have upgraded smokers who found Gold Flake Filter Kings too light and expensive.

In 1984, the first in the series of the ‘Gracious People’ campaign was released. The research studies showed that Gold Flake Kings Filter smokers fell in the age group of 33-40 years, over 60% were graduates and had a personal monthly income of Rs.3,000.

In 1986, because of the government policy announced, the cigarettes were taxed and the excise duty was made progressive, payable depending upon size as compared to flat percentage of retail price before.

After there years of running of gracious people campaign in 1987, consumer feed-back suggested that the life style and personality of the Gold Flake Filter King consumer wasn’t getting through.

And in 1987, the advertisement was reviewed again and the ad agency clarion developed for the gracious people campaign, the movie hall version of which had an elegantly dressed host couple showing off an exquisite couple showing off an exquisite telescope to a guest couple (in a formal Indian attire) in a elaborately done up bungalow.

In January 1988, ITC changed Gold Flake Filter Kings packaging with a new red and gold pack and reemphasized the gold association in the process. In the subsequent successive union budgets, the government raised the excise levy on king sized smokers and in this process the Four Square Kings a value for money brand found itself priced out of the reach of many.

As Gold Flake was not positioned towards price, it did not loose the customer segment. By 1991-92 Gold Flake King was selling about 300 million sticks per month, as the excise rose, sales dipped to a monthly 280 million sticks a month in 1992-93.

Meanwhile several other brands started using gold as a predominant colour for visual appeal. Gold Flake King size existing campaign was reportedly acquiring consumer fatigue. It was now staid and overly formal. A weakness was that it cued inherited wealth, and passed down privileges were beginning to lose their place of pride.

Also the entire graciousness theme was beginning to 100k rather affected in a society that was taking rapidly to spontaneity. So the brand went in for a near total image change. ITC targeted the energetic young achiever rather than the older, status groomed smoker.

‘Celebrate the feeling’ replaced the ‘gracious people’, and the couples moves out door – to the beach, on a trendy dune- buggy, and dressed in T-shirts and shorts. But, as ITC quickly discovered, it had gone over the top. In trying to endear itself to the new generation consumer, the brand distanced the more conservative smoker. The young, sporty imagery was just too divergent from the regal sophistication of the gracious years.

Though the campaign did not have any negative impact on brand’s sales, ITC withdrew it and replaced it with something in between. The two couples are young but not collegian, indoor but out in the verandah, fairly relaxed but not frivolous, modernly clad but not too casual. The present campaign is targeted at the sociable, ambitious and westernized consumer.

In the past few years, ITC has been concentrating on building signage. The red and gold logo is to found on thousands of glow sign kiosks in the metros. These not only act as ads, but also give the approaching consumer an experience of the brand’s character at the point of purchase.

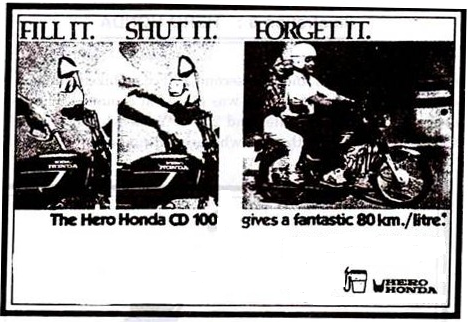

Example # 8. Hero Honda:

Hero Honda was launched in 1985 and was second 100 cc mo-bike launched after IND-Suzuki in 1984. In 1984, the market for motorcycles was placed at around 1.9 lakhs per unit per year and 175 cc Rajdoot, 350 cc Enfield Bullet and 250 cc Yezdi which appealed to the consumer looking for power, thrill or both, to the one who needed plain conveyance, a scooter was the best option.

Hero Honda when it was launched it positioned the brand Hero Honda CD 100 on fuel economy of 80 km a litre almost twice what a scooter was known to give. The selling preposition worked and Hero Honda became the market leader defeating Ind. Suzuki. In 1986. Ulka, the advertising agency came with the catchy slogan ‘fill it shut it forget it’.

The product was sold through exclusive dealers who got the right to do so only after promising to adhere to HHML’S guide lines on display space and merchandising. Though it was available in four regions of the country by the end of the first year, it took another year for CD 100 to go national. By this time, it had two other 100-cc competitors—Yamaha RX 100 from Escorts and Kawasaki Bajaj RTZ from Bajaj auto. Both these had two stroke engines, which meant that they took more petrol, but performed better on speed acceleration and were better driven to rough handling.

Hero Honda CD felt a minor tug where Yamaha Rx-100 struck on aggressive ‘power’ stance and decided to show up the down side of a four stroke engine by repositioning CD 100 as a delicate mobile. “When they talk about how long the fuel will last’, ‘said on RX 100 ad, think about how long the bike will last’.

The idea range home to young collegiate buyers from relatively wealthy homes. And thankfully for Hero Honda, there were more people concerned about the rising cost of petrol than the bike’s ability to do ‘wheelies ‘or win a motor cross. The product held firm with the unflashy family man and young career starter. In 1987-88 (July-June), sales grew by an impressive 96 per cent to about 84,700 units.

As Hero Honda did not want to dilute its rational appeal, so through its ad agency HTA, created a campaign featuring ordinary youngsters testifying to CD 100’s.

Secondary Benefits:

Low pollution and relatively less maintenance costs, among others. The ad line: ‘You’ve got a good thing going’. The effort paid off and CD 100 retained its no 1 slot in 1988-89, recording sales of over 74,000 units in the last three quarters of the financial year (this was when the company adjusted itself to the April-March accounting period). But that wasn’t enough.

The style segment was growing rapidly, the market was evolving to a higher level of sophistication and the company needed to widen its range of offerings. Finally, in 1989, the company unveiled Hero Honda Sleek, priced at Rs.22,553 (on road) a Rs.3,000 premium on CD 100.

A reskinned version of the original, sleek was designed to stand by its name. It was advertised on life style and attempted to talk in the language of youth. ‘What’s life without a little passion?’ asked the print ads, while TV commercial showed a young man impressing a girl with his wonder machine. Of the 26,000 initial bookings received for sleek, claims HHML, over 24,000 came from people of the targeted profile.

Initially the company faced some problems in switching its production lines. But within a few months after they were sorted out, sleek accounted for one in every fourth bike. Simultaneously, efforts were made to get closer to the consumer in terms of after sales service. HHML initiated the concept of mobile service vans in 1990.

These were complete work shops by themselves, and could be spotted on routs which lacked a service centre for miles on end. Beginning with one such in the north, the company now runs six of these in different parts of the country. They also accumulate data on high vehicular regions to assess where it is worth setting up permanent service points.

Sleek helped the brand attain sales of over 1.2 lakh units in 1990-91 growth of 83 per cent from the sleek less year before. Next on HHML’S agenda was an attack on the small town and rural markets, which were still ruled by the hardy Rajdoot. So HHML took on Rajdoot’s territory in 1991 with Hero Honda CD 100 cc.

Priced at almost Rs.30,000 (slightly higher than CD 100), the claimedly more powerful version of the original had some fundamental design changes. It had larger tyres (for better ground clearance), stranger suspension and an ‘engine guard’. While it was designed for the rural buyer, the ads, in vernacular, was the hearts of the small town dweller too.

But the long suffering TVS Suzuki was reviving up for a mighty come back. It was on a launch spree, having unveiled its ‘no problem bike’ Suzuki Samurai in October 1992, followed by the powerful 110 cc Suzuki Shogun. Urban India was taken by storm by these high performance two stroke bikes.

The former rode on beauty, the latter on power. As TVS Suzuki revived, it started threatening Sleek. At one point, it even looked as though sleek would be forced to give in roll over and play dead before the superiority of Samurai.

HHML Surveyed the scenario for the possibility of marketing superior 100 cc four – stroke mobike. If it was to be the bike of the future, it though, the value offering would have to be right. No just fuel efficiency, which had all but worn out as a puller for young urban buyers by 1994, but something more. HHML needed a better avatar of sleek.

Thus, came Hero Honda Splendor in 1994, to take the place of sleek (currently on the company’s export list). Splendor, which HHML refers to as ‘tomorrow’s technology today’, was launched as a brand with its own identity. The company has tried hard to distance splendor from its relatively unclassy cousin – CD 100 in consumer perception.

At around Rs. 39,000, splendor is Rs. 3,500 more expensive than CD 100 and boasts an ergonomically superior double cradle tabular frame. Among other design pluses the mobike’s air feed inlet is higher- just below the seat rather than close to the ground – which keeps dust particles from getting in and playing havoc.

While CD 100 continues selling to the price conscious, splendor spares no effort in show casing it self as premium. The ad-line: ‘designed to excel’. The fuel economy benefit isn’t read aloud, it is implicit.

In consonance with splender’s glittering image, the company set up automated repair work shops that operate with high-tech pneumatic tools. A consumer here gets to relax and observe, through a glass partition, the work being carried out on his mobike.

Today, HHML oversees the operations of 109 such workshops in the country, and intends raising their number to 200 by 1996 end. Similar efforts are being under taken by 338 exclusive sales and service dealers in 305 towns and cities. Also 86, centres service Hero Honda bikes and stock spare parts in areas with heavy vehicular population.

To avoid being caught in a mono – product fix again, HHML says that it is keeping its ear to the ground to detect new needs. Umbrella brand equity building campaigns, in the meantime, will serve the purpose of holding the consumer’s attention.

Its Rs. 2 crore ‘we care’ eco-friendly campaign, handled by Maadhyam, an example of this. ‘Come April 1996’, says one ad, ‘some bikes may go into hiding. Just a warning to those who haven’t been following global standards in fuel emission’.

Example # 9. Captain Cook Atta:

DCW Home Products Ltd was born in 1989 as a subsidiary of Mumbai based DCW (formerly Dhram gadhra chemical works ltd) and its first offering was captain cook salt in 1991 which was a grand success. For the Captain Cook Atta penetrative pricing Rs. 21 for 2 kg. pack was chosen to get the most trials.

Innovative packaging, clean looking plastic as contrasted with rough gunny bags was the differentiating point to avoid falling into the usual low margin, low differentiation commodity trap.

The major problem with atta marketing is that being the homogenous product, it lacks strong differentiating points and on the other side there was no national flour brand with which it had to compete. Though NEPC Agro Trupthi came close to being one but it is still testing the waters. And the regional brands like Shakti Bhog were fighting on price.

As the over whelming majority of consumers preferred neighbour hood chakkis with the reason: hygiene, strengthened by the assurance of involving oneself in the act of selecting the wheat grain and then having it ground in one’s presence without any inconvenience.

The above stated scenario, the company faced the problem of positioning of brand. As the company thought that the convenience appeal has no meaning to position the atta, the captain cook atta was positioned with the adline lachhedar Paranthon Ke liya (for layered paranthas) in the Pune launch. This was having least impact with the housewives who were more concerned with quality.

So the advertising agency Ulka positioned the brand with the line Sone jaise gehun se bana (made from gold like wheat grains) and the effect was high lightened in the launch spot by bathing it in a golden glow.

This ad showed a fairly up market farmer coming home to dinner while grumbling about the fellows from a company called captain cook who is so fussy about selecting the right size and quality of grain. Unknown to him the chapattis he is chewing on are made up of captain cook atta.

He comes to know of that only after he has had more than the usual number. Expressing awe, he nevertheless grudgingly asks for another one. This film was broadcast intensively and supported by hoardings and print ads. Doing by recall and the brand’s awareness, the spot can easily be called a success.

Six months after the captain cook atta launch, a bigger 5 kg. pack was introduced and by the August 95 the company had sold nearly Rs. 11 crore. The figure was by no means an indicator of the brand’s national presence.

As the company discovered, captain cook atta’s sales were greater in the south and west even though wheat flour formed part of the North’s staple diet. Precisely, it was a question of conversion. Habits in the north were well in grained while a south Indian family could always try out a new 2 kg pack.

It was felt that the earlier ad campaigns had consumers pre disposed positively towards the brand but not many were actually buying it. In the meantime, a sales promotion scheme, promising a 3m scrub pad (worth Rs. 8) with every 4 kg of captain cook atta, was run in 1995.

It flopped. On hindsight, the company feels it happened because of the novelty of both the products. A Rs. 7.50 price off announced last year on every 5 kg. pack and it succeeded.

The atta price was moved up to Rs. 14 a kg. Though still competitive, it wasn’t enough to ‘ ensure profits. Earnings would come from a loyal consumer base which valued the brand so much as to pay a premium for it. The company had to speed up conversions to gather that loyal base.

Yet, the housewife had to be swayed towards the standardised captain cook atta. The obvious move: create dissonance on the prevalent buying behaviour.

According to the company, sales are picking up strongly, more so in the north. That, in spite of competition from Hindustan Lever’s Annapoorna. Monthly sales are averaging 3,000 tonnes, claims DCW HPL and rising, as against some 1,000 tonnes sold each month.

However, the hygience appeal, as DCW HPL now reorganizes, has its limits. The housewife who visits the chakki today does so out of her caring attitude, believing that to be the right thing. Interestingly, milcent domestic flour mill, which pitched itself on the hygience platform came a cropper.