After reading this article you will learn about:- 1. Introduction to Careers in Management 2. Career Effectiveness 3. Career Stages 4. Career Patterns 5. Management as a Career 6. Characteristics of Effective Managers 7. How does one Plan a Management Career? 8. Career Planning Benefits.

Contents:

- Introduction to Careers in Management

- Career Effectiveness

- Career Stages

- Career Patterns

- Management as a Career

- Characteristics of Effective Managers

- How does one Plan a Management Career?

- Career Planning Benefits

1. Introduction to Careers in Management:

Individuals not trained as managers often find themselves in managerial positions. Many individuals presently being trained to be teachers, accountants, musicians, salespersons, artists, physicians, or lawyers will one day earn their livings as managers. They will manage schools, accounting firms, orchestras, sales organisations, museums, hospitals and government agencies. – James H. donnelly, Jr.

The term ‘career’ may be defined as “the individually perceived sequence of attitudes and behaviours associated with related experiences and activities over the span of a person’s life”. In this definition, the stress is on two things: attitudes and behaviours in an ongoing sequence of work-related activities. However, a person’s non-work life also plays an important role in his(her) career building and career management.

It is also necessary to bring into focus the implication of career from an individual’s point of view as also from the point of view of the organisation. While an individual’s career involves a series of choices from among different opportunities, from the organisation’s point of view, a career involves processes by which the organisation renews itself.

In the contemporary business world, the term ‘career’ has to be broad enough to include not only traditional work experiences, but also emerging work and lifestyles. This simply means that career development practices recognise the diversities of individual choices and career alternatives.

In recent years a number of companies have undertaken self- directed career development programmes. For instances, British Petroleum Exploration has placed responsibility for career development in the hands of employees.

2. Career Effectiveness:

There are four characteristics of career effectiveness which is judged not only by the individual, but also by the organisation itself — performance, attitude, adaptability and identity.

1. Performance:

Perhaps the two most important indicators of career performance are salary and position. To be more specific, the more rapidly one’s salary increases and advances up the hierarchy, the higher the level of career performance. As one advances (due to promotion), one’s responsibility also increases in terms of employees supervised, budget allocated and revenue earned.

However, what is of relevance to the organisation in career performance is its direct relation to organisational effectiveness. This simply means that the rate of salary and position advancement reflects, in most cases, the extent to which the individual has contributed to the achievement of organisational performance.

Two related points may be noted in this context. Firstly, individuals are unlikely to realise their career effectiveness when the organisation’s performance evaluation and reward processes do not fully recognise performance. This implies that individuals may not receive these rewards, the salary, and the promotions associated with career effectiveness because the organisation is unable or unwilling to provide them.

Secondly, individuals may perform to their potential and are satisfied with career performance. But organisations expect more and are thus dissatisfied because, on most occasions, the performances of individuals fall short of their potential (since individuals have other non-job interests). This mismatch occurs as a consequence of the individual’s attitude towards the career.

2. Attitudes:

In management literature, the term ‘career attitudes’ refers to the ways individuals perceive and evaluate their career. Individuals having positive attitude toward careers will also have positive perceptions and evaluations of their careers. Such attitudes are likely to have important implications for the organisation inasmuch as individuals with positive attitudes are more likely to be committed to the organisation and to be involved in their jobs.

The important point to note here is that positive career attitudes are likely to coincide with career demands and opportunities that are consistent with an individual’s interests, values, needs and abilities. Another point to note here is that specific career attitudes such as career commitment and job involvement are associated with behaviours that have direct relevance for organisations.

3. Adaptability:

Most contemporary professions are characterised by constant change and development. So, there is need to acquire new knowledge and skills to practice a profession. Individuals unable to adapt to various changes and adopt them in practice of their careers run the risk of early obsolescence and the loss of their jobs.

Other individuals complain of ‘burnout’ when they are unable to adapt to the constant demands of their job or career, more so when the sense of burnout occurs late in their careers.

In the past few years, management personnel have been particularly vulnerable to downsizing. As a general rule managers suffer proportionately greater job loss as organisations downsize. This lack of employment security is now causing managers to reconsider the wisdom of planning their careers within a particular organisation.

There is no denying the fact that an organisational benefits through the adaptiveness of its employees. The money spent by organisations for employee training and development indicates the mutual benefits derived from career adaptability. Thus, career adaptability means the application of the latest knowledge, skills and technology in the work of a career.

4. Identity:

There are two important components of career identity. The first one is the extent to which individuals have clear and consistent awareness of their interests, values and expectations for the future. The second one is the extent to which individuals view their lives as consistent through time, the extent to which they see themselves as extensions of their past.

In truth, effective careers in organisations are likely to occur for individuals with high levels of performance, positive attitudes, adaptiveness and identity resolution. Furthermore, effective careers are inseparably linked to organisational performance.

3. Career Stages:

As a general rule, individuals move through four distinct stages during the course of their careers, viz., establishment, advancement, maintenance and withdrawal.

1. Establishing a Career:

The establishment stage occurs at the start of one’s career. During establishment, individuals need support from their managers. Those managers who recognise this assume the role of mentor.

2. Advancing a Career:

This stage refers to the period of moving from one job to another, both inside and outside the organisation. During this phase, the managers have much less concern for security-need satisfaction and more concern for achievement, esteem and autonomy.

Two main characteristics of this stage are:

(i) Promotions and advancements to jobs with responsibility; and

(2) Opportunity to exercise independent judgment.

But it is not quite clear at this stage, as to what are the specific factors that explain why some individuals advance while others fail to do so.

3. Maintaining a Career:

This stage arrives when one has reached the limits of advancement and he(she) concentrates on the job he is doing. At this stage, people in organisations make efforts to stabilise past gains. At this stage, an individual gets opportunity to show creativity inasmuch as he has satisfied most of his psychological and financial needs associated with earlier phases. Esteem need seems to be the most important at this stage. And, many people experience some sort of mid-career crisis during this phase.

These people are not successfully achieving satisfaction from their work and may, consequently, experience physiological and psychological discomfort. And, as a consequence, they may also experience poor health and growing anxiety. Since they do not want to advance further they underperform. They then lose the support of their managers which intensify their health and job problems further.

Managers in the maintenance stage should act as members of those still in the earlier stages of their career development. They also tend to broaden their interests and deal with people outside the organisation in increasing numbers. Thus, at this stage the activities of manager, centre around training and interacting with others.

Since they assume responsibility for the work of firms, they are subject to considerable psychological stress. Those who cannot cope with this new and different requirement may decide to return to a previous stage. Others may just be satisfied seeing some of their peers move on to bigger and better jobs. They are quite comfortable to remain in the maintenance phase until their retirement.

In their role as mentor, managers can make important contributions to the career development of their proteges. The mentor counsels, guides, supports and protects the less experienced protege. As J.H. Donnelly has put it: The mentor can help the protege by sponsoring (recommending the protege for promotion), providing visibility (creating opportunities for the protege to demonstrate special skills and talents) coaching (suggesting ways to handle demanding and difficult tasks and situations) and protecting (steering the protege away from controversial situations).

Managers can mentor one or multiple proteges, and the mentor relationship can develop informally (initiated by the mentor or prospective protege) or formally. In formal mentor programmes, the organisation has to match mentors with proteges.

Successful mentor relationship is likely to advance a beginning in the manager’s career in the organisation. However, the mentor relationship has potential pitfalls. Proteges often resent their mentors and believe that they are overworked, too heavily scrutinised by the mentors, and too closely identified with them. Proteges are also frustrated when their mentors publicly reprimand them for poor performance or performance mistakes.

The mentors, in turn, believe that heavy Workloads and public criticism are necessary to avoid the criticism of doing favours to some at the expense of others. In short, mentor relationships, while potentially beneficial for both mentor and protege, can ones relationships to manage and maintain. Besides mentioning the maintenance stage manager can enhance his (her) career development by developing peer relationships.

In fact, in a typical organisation hierarchy there exist a continuum of peer relationships. The relationships may be classified as information peer (information sharing) collegial peer (job-related feedback, friendship) and special peer (emotional support, confirmation).

Those three types of peer relationship are perceived somewhat differently by individuals at different career stages. Individuals at the early stages of their career use information peers to learn the techniques of doing or accomplishing a task, they use collegial peers to help define their professional role, and they use special peers to acquire a sense of competence and to help manage the stresses and anxieties of work and developing familiarities. Men commonly mentor women who want to advance their managerial careers. But for people without a mentor, peers can be a valuable source of help, support and encouragement.

Withdrawing from a Career:

The withdrawal phase follows the maintenance phase. The individual has, in effect, completed one career and will try to experience self-actualisation through those activities (including social and voluntary services) which could not be pursued while working.

Studies indicate that high performers pass through each phase; they do not skip over them. Moreover, individuals who grow older without advancing to the appropriate phases are seemingly less valued than those who do.

4. Career Patterns:

Effective advancement through career stages involves moving along career paths. From the organisational point of view, career paths are important inputs into human resource (manpower) planning. An important aspect of manpower planning is assessment of a company’s future manpower needs, which depend on the projected passage of individuals through the ranks.

From the point of view of the individual, a career path is the sequence of jobs which he intends to undertake to achieve personal and career goals. It is very difficult, if not impossible, to completely integrate the needs of both the organisation and the individual in the design of career paths. Yet systematic career planning has the potential for closing the gap to the maximum extent possible.

As a general rule career paths emphasise upward mobility in a single occupation or functional area. Each job is reached when the individual has garnered the necessary work experience and ability over time and has demonstrated that he is ready for promotion. Implicit in such career paths are attitudes that an individual fails whenever he does not move upward after a specified time period.

In most organisations, career path refers to the idea of moving upward in the organisation along a single ‘path’, which is usually the managerial or line path. What about staff members? Staff people are often prevented from moving upward unless they give up their speciality and move into a live position. It is high time organisations began recognising the importance of multiple paths as well as career planning.

As one moves upward along a career path the number of job openings declines, and the number of candidates increases as one approaches the top of the organisation. Indeed the performance of all types of organisations — business and non-business (such as universities, hospitals, charitable trusts) depends on the effectiveness of managers. Their careers follow some general stages, although there is no single correct path to a successful management career.

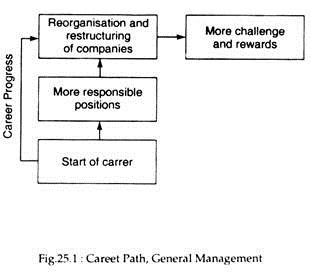

The essence of the concept of career path is that career progress occurs when one moves up the organisation hierarchy to positions with progressively more responsibility, challenge and rewards. In today’s complex business environment, it is becoming increasingly difficult for most employees, especially those in large organisations, to move upward.

This is more so in view of the fact that the merger wave and growing complexity of the environment led to major reorganisation of many companies. Due to those restructurings many a job has been eliminated and as a consequence, the number of levels in the organisational structure has been reduced. See Fig.25.1 which is self-explanatory.

These moves led to the emergence of leaner and more flexible organisations and have thus changed the nature of the traditional, upward career path. A recent theory of Fortune has indicated that today there are very few positions in the middle and upper levels of organisations for individuals who want to move upward, even if they are higher qualified and competent enough to do so. This tend is likely to continue in the 21st century, given plans in the many organisations to further restructure and reduce the size of their management workforces, i.e., downsizing.

Plateaus:

Due to the current trends towards downsizing, corporate restructuring through mergers and acquisitions (M&A) and emergence of leaner organisations and intensely competitive environments most employees are reaching a plateau in their career paths. The term ‘plateau’ refers to the point in a career where the likelihood of further movement up the hierarchy is very low.

Nowadays employees are reaching the plateau (the final point of ascent in one’s career) sooner than two decades ago. Industrial psychologists feel that a career plateau is a frustrating dilemma for most employees who think that their careers have reached a dead end. Many others suffer from a sense of frustration and personal failure.

Zigzag Career Paths:

All employees do not follow the same upward moving straight line career path. In order to avoid a career plateau some employees adopt a zigzag career path; they leave the organisation and try to move upward by changing companies or even industries. A zigzag career path (especially one across industries) involves risk because, with each job, the employee had to learn a new culture of doing business.

After all, managing is an art, based on human judgment and environmental adaptation. Studies indicate that such career paths are being more and- more popular over the years. This is so because managers are willing to take the risk for potentially greater professional growth and career rewards.

Plateaued employees who remain with a company may accept a lateral transfer not only to broaden their managerial skills but also to take up new challenges. In some work situations, a lateral transfer is likely to open a new path upward. There are also employers who get more and more involved in training young managers in their areas of expertise.

Others strive to improve their marketable skills by more investment in human capital as also by developing public relatives mainly by extending their outside activities, i.e., activities outside the job. At the same time, more and more companies are focussing on career development and training programmes and organising seminars that focus on improving a manager’s satisfaction with his present job in two ways: (i) by better matching aspects of the manager’s likes with his talents and (ii) by giving the manager added responsibility.

Dual Career Paths:

In the mid 1970s a new concept was introduced. This is known as the dual career path. The concept was designed to provide non-management professionals (e.g., scientists, engineers and various technically qualified people, R&D specialists), with the opportunities to move up a career ladder, receiving the same compensation while still working in their professional fields.

The dual career path was introduced to retain talented professionals who suffered from frustration due to the lack of advancement opportunities in the organisation unless they were assigned management tasks (which many did not want to do).

However, the dual career paths were largely unsuccessful in the early days, i.e., in the mid-1970s when they were created. The fact is that the management path to achievement is so ingrained in organisation cultures that the dual career paths lost touch with reality and thus were not treated with favour.

In fact, both managers and professionals did not treat them as legitimate. Studies indicate that, in most cases, the dual ladders were poorly maintained and the rewards even were not commensurate with those provided for employees on managerial career paths.

However, a recent survey made by Business Week indicates that in the late 1980s, more and more organisations started developing dual career paths for many types of professional employees (e.g., sales people, bank loan officers, service representatives) and are now taking sufficient care to communicate the path options to professional employees and to make sure that the path’s rewards correspond to those in managerial career ladders.

A report indicates that in some organisations plateaued managers with strong professional background are being given the opportunity to change to a dual career path. From that point, they resume their professional work and choose to remain managers; however, opportunities still exist for moving upward along the career ladder.

5. Management as a Career:

To make an overall assessment of management as a career it is necessary to have a broad idea of what managers do and are expected to achieve. Managers are supposed to manage three aspects of an organisation: work, people and operations. They plan, organise and control individuals, groups and organisations.

They are also called on to motive people and groups, to provide leadership and to sense, recognise and provide for change. Modern managers also use information to make decisions that either directly or indirectly affect efficient production and operations.

Managing Work and Organisation:

Today’s management practice is based on three points:

(i) the principles of work measurement and simplification,

(ii) principles of planning and organisation and

(iii) basic control techniques.

Managing People:

This is perhaps the most challenging and difficult aspect of the manager’s job. Since people are unique, managing them to achieve effective levels of individual and group performance demands knowledge of individual differences, motivation, leadership and group dynamics. And, since no theory of motivation is able to predict what any individual will do in a specific situation the art management lies in modifying theoretical predictions as and when necessary.

Managing Production and Operations:

All organisations whether producing goods or rendering services, exist to achieve results. And, the production and operations function refer to the process of acquiring and combining the physical and human resources to achieve the desired results. It is the task of managers to achieve effective and efficient performance of this key function.

Management is an applied discipline. It is more an art than a science. Science provides, a framework of analysis. But successful conduct of management functions requires human skill and judgment.

In fact, as Donnelly has commented: “Unlike medicine and engineering, there is no science of management per se. Instead, management takes theories and concepts from all relevant sciences. Thus, effective managerial performance results from choosing an appropriate theory and technique for a particular problem or situation that arises in the manager’s job”.

In order to answer some important and relevant questions about careers in management, it is necessary to clearly identify the job of a manager. We will be addressing ourselves to this issue now.

Who should pursue Management as a Career?

The trait theory of leadership fails to predict who will become a leader. It is also difficult to predict, on the basis of existing theory, who will be achieving a successful career in management because various factors play a role in an individuals’ management career.

Two important factors — which are within the control of a manager and may bring success, are effective career planning and a strong educational background. However, there are various other factors which are external to and beyond the control of an individual manager’s influence.

These environmental factors also determine who will achieve a successful career in management. For -example, a faltering organisation may undergo a reorganising that may just lead to the end of a manager’s job, thus depriving him from the opportunity of gaining further management experience that contributes to improved skills. Luck — which is beyond a person’s control — may also substantially influence an individual’s career.

Of course, the importance of these external forces do not disprove the fact that certain individual characteristics significantly enhance a manager’s chance of becoming ‘effective’.

6. Characteristics of Effective Managers:

No doubt, many characteristics contribute to management effectiveness. The list is almost endless.

However, two of them deserve special consideration in the context of management as a career:

1. The will to Change:

Managers achieve results through other people. This is the essence of management — its most fundamental characteristic. The desire or need to influence the performance of others and the satisfaction derived from doing so is called the will to change, which, in its turn, is related to various factors such as favourable attitude towards authority, desire to compete, assertiveness, drive to exercise power, desire to set oneself apart from others in the group, and sense of responsibility. However, the will to manage can be developed and strengthened through training.

2. Supervisory Ability:

It is supervisory ability that largely distinguishes effective from ineffective managers. As Donally has found, on the basis of his own empirical studies: “Effective management involves utilising the correct supervisory tactics required in a particular situation. The ability to use appropriate supervisory practices implies a contingency orientation towards management. Effective managers recognise and apply the relevant elements from each of the approaches of management, are responsive to changing social and economic conditions and can motivate people”.

And, since each approach to management contributes to the body of management thought and practice, effective careers in management are related to the ability to select the appropriate idea for the situation.

Ability to Assess Potential for Effective Management Career:

Individuals can use personal initiative to judge their managerial potential, i.e., to find out whether they really want and are suited for a career in management. No doubt, with the assistance of a counselling professional, individuals can reach some tentative understanding of their potential.

However, with our present state of incomplete knowledge, it is not possible to predict which variables conduce to management success. In such a situation, the stress should be on tentative understanding of whether one wants to manage and has, or can develop, the ability to manage. Controlling these two’ different but interrelated issues is the first step in career planning.

7. How does one Plan a Management Career?

Career planning is essentially matching an individual’s career aspirations with the opportunities available in an organisation. This is different from career pathing, i.e., the sequencing of specific jobs associated with those opportunities. These two processes are different, but interrelated.

While the former demands identification of the activities and experiences needed to accomplish career goals, the latter involves considerations relating to the sequence of jobs that results in reaching these career goals.

No doubt career planning as a practice is still in embryo. Still, various organisations are turning to career planning as a way to be proactive about — rather than reactive to — problems associated with ineffective management careers.

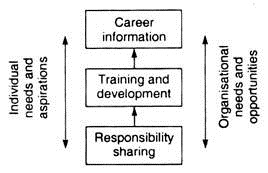

Fig. 25.2 describes a typical career planning and planning process. Successful practice is based on responsibility sharing. Most modern organisations place equal responsibility on the individual and the organisation. Career planning is typically based on striking a balance between individual needs and aspirations and organisational needs and opportunities.

Prima facie, individuals have to identify their aspirations and abilities and, through counselling, recognise the training and development required for a particular career path. At the same time, it is absolutely essential for organisations to identify their needs and opportunities and, through manpower planning, provide career information and training to their employees. For career planning to proceed smoothly, it is essential that employees have with them latest information about career paths, expected vacancies and position requirements.

Fig 25.2 : A Career Planning Process

Various techniques may be used for matching individual and operational needs. The most widely used practices in leading U.S. companies are informal counselling by the personnel staff and career counselling by supervisors. Some companies use less common but more formal practices such as workshops, seminars and self-assessment centres.

Informal Counselling:

The organisation’s personnel function may also include counselling services for employees desirous of assessing their abilities and interests. In most modern organisations supervisors include career counselling during their performance evaluation sessions with employees. A characteristic of effective performance evaluation (appraisal) is to clearly inform the employee not only how well he has done, but also what the future holds.

Thus, it is of paramount importance for supervisors to be able to counsel the employee in forms of organisational needs and opportunities not only within the specific department, but throughout the organisation. Since supervisors usually have incomplete information about the total organisation, they must adopt more formal and systematic counselling approaches to be able to value the performance of the employees properly.

Formal Counselling:

To serve the interests of some specific employee groups, organisations often use such formal practices as workshops, assessment centres and career development centres. The number of companies using these techniques is increasing. So far two groups have received most attention, viz., management trainees and ‘high-potential’ or ‘fast-track’ management candidates.

Most employees sooner or later reach the limit of their growth opportunities (progress) within the organisation. The number of jobs just falls behind the number of employees, more so in view of recent downsizing, which reduces the number of jobs per employee even further. But if most employees are to survive, they should never reach the limit of their progress in developing skills and abilities to perform their existing jobs in a much better way.

Other Human Resource Management Practices:

Modern organisations use various personnel practices to facilitate their employees’ career plans. Perhaps the oldest and, at the same time, the most widely used method is some form of the tuition aid of programme. Employees can enroll in nearby educational institutes and the organisation reimburses all, or part, of the course fee. Some companies provide in-house courses and seminars, plus tuition reimbursement for courses related to the individual’s jobs.

Another practice is job posting. The organisation publicises job openings to employees.

Such job posting should meet, at least, the following conditions:

(i) Posting should include promotions and transfers as well as permanent vacancies.

(ii) Available jobs should be posted a few weeks prior to external recruiting.

(iii) Eligibility rules should be clearly specified so that there is no ambiguity.

(iv) Selection standards should be stated in clear terms.

(v) Vacating employees should be given the opportunity to apply ahead of time.

(vi) Unsuccessful candidates — i.e., employees who apply but are rejected — should be notified in writing, and a reason of failure should be recorded in their personnel files.

No doubt different counselling approaches are used. However, the crucial element of success of each approach is the extent to which individual and organisational needs are satisfied.

8. Career Planning Benefits:

Career planning is becoming more widespread in most modern organisations. So, it logically follows that individuals who wish to make formal career plans should join those organisations that have demonstrated a commitment to career planning.

However, all people in a typical organisation do not gain from career planning. In fact, some individuals gain very little from the process. Studies have indicated that career planning is most effective for people who have relatively high needs for growth and achievement, the skill to carry out their career plans, and a past history of career successes.

However, this does mean that career planning is for the select few and some people gain at the expense of others. However, research findings indicate one thing clearly at least: organisations should try to identify people who are most likely to take advantage of career planning programmes.

For career planning an individual should not rely on company- sponsored programmes.

He(she) must have the initiative and use his own resources to join a programme on his own — either inside or outside the organisation so that he is able to answer the following three questions:

1. Do I really want to be a manager?

2. Do I have the ability to be a manager?

3. How do I go about having an effective career in management?