The following article will guide you about how to build a super-efficient company.

Tearing Down Walls of a Company:

To get a clearer view of the prodigious costs of uncoordinated intercompany processes- and the great rewards of integrating them-look at the recent experiences of Geon, a chemical company based in Ohio. Geon spun off from BFGoodrich in 1993. Through organic growth and a series of acquisitions and joint ventures, it established itself as the world’s largest producer of polyvinyl compound (PVC), garnering revenues of $1.3 billion in 1999. (Last year, Geon merged with another chemical company, M.A. Hanna, to form PolyOne.).

Through most of the 1990s, Geon was vertically integrated business. It brought chlorine and ethylene and combined them to create the basic raw material for PVC, vinyl chloride monomer (VCM). It then transformed VCM into resins and, through a series of additional steps, into various compounds used in products ranging from computer housings to home appliances.

Like many industrial companies, Geon focused its energies in the mid-1990s on breaking down the walls between its units in order to reduce costs and create greater value for customers. The company followed a program that is by now familiar- integrating and simplifying core business processes and installing ERP systems to support them.

By allowing information and transactions to flow more easily among different parts of the company, Geon profited handsomely. The percentage of orders shipped on time soared, customer complaints almost vanished, the need to pay premium freight rates to make up for scheduling foul-ups evaporated, inventory levels fess sharply, and overall productivity got a strong boost.

Geon’s costs dropped by tens of millions of dollars, and its working capital fess from more than 16% of sales to less than 14% shift; Recognizing that it did not have the sales volumes necessary to produce VCM and resins at a competitive cost, the company decided to focus entirely on the compounding side of the business. Producing compounds was ha higher -value- adding activity, and it was less dependent on scale and more reliant on clever engineering to meet specific customer needs.

This new focus would give Geon the opportunity to gain a true competitive advantage and to widen its margins. In support of the new strategy, Geon divested its VCM and resins operations to a joint venture with Occidental Chemical called OxyVinyls, which become its primary supplier of materials.

While Geon’s actions were strategically sound, they were operationally disastrous, In effect; Geon erected a high (intercompany) wall where it had just demolished a low (intercompany) one. VCM and resin production had only recently being integrated with compounding and now they were again integrated with compounding, and now they were again torn asunder, this time becoming parts of separate companies.

The results were all too predictable; Work was no longer coordinated, information was no longer shared, and overhead and duplication were reintroduced. Expediters, schedulers, and a host of clerical personnel had to be hired to manage the interface between Geon and OxyVinyls. Data had to be entered twice, resulting in an 8% error rate on orders that Geon placed with OxyVinyls – wrong purchase- order numbers, product numbers, prices, and so on, The time needed to process orders also jumped as communications become more formal and interfaces more complex.

On the production side, as Geon and OxyVinyls become less aware of each other’s inventories, shipments, and levels of demand, their manufacturing processes become more irregular, requiring many stops and starts, delays, and unexpected changeovers. Geon’s horizon for production planning was dramatically foreshortened, from about seven weeks to about three.

Its inventories increased 15%, its working capital went up 12% and its order-fulfillment cycle time tripled. Not only had Geon lost the earlier benefits it had gained by painstakingly integrating its businesses processes, but also in many ways the situation become even worse than it had been before Geon’s internal wall bashing.

Geon’s problems may appear particularly dire, but they were actually no worse than those faced by most companies. There was, however, one crucial difference- Geon saw them. Its rapidly decaying performance underscored to management the huge penalties of disjointed intercompany processes. Rather than ignoring the inefficiency of dismissing it as the inevitable consequence of working with other companies. Geon took action. It worked closely with OxyVinyls to connect both companies’ processes and the computer systems that supported them.

The two companies tightly integrated their forecasting process; now, as soon as Geon uses information from its customers to predict demand for compounds, that forecast is transmitted, over the Internet, to OxyVinyls, which is incorporates it into its own forecast for resins and monomers. Ordering and fulfillment processes are also tightly knit. Within 24 hours of receiving an order from one of its customers, Geon translates the order into the materials it will need from OxyVinyls and automatically dispatches an order directly into OxyVinyls’ fulfillment process and system. In turn, order acknowledgments and confirmations, advance shipment notifications, and invoices automatically go from OxyVinyls back to Geon.

The jobs and behavior of employees involved in the processes have changed significantly as a result. Production planners in one company, for example, no longer have to waste time trying to find out what’s going on in another company. Instead, they can concentrate on solving problems in ways that benefit both companies.

When there are tight markets for raw materials, for instance, planners from Geon and OxyVinyls work hand-in-hand to reschedule production runs and shipments to ensure that plant capacity is used as efficiently as possible. Geon’s people also better appreciate that small orders increase OxyVinyls’ shipping costs, and they now look for opportunities to consolidate purchases. They know that when OxyVinyls’ costs go down, so do the prices of the products it sells to Geon.

Performance measures have also changed. Geon’s purchasing agents used to be evaluated primarily on the prices they negotiated for materials. Even though the availability of materials is critical to manufacturing productivity, that factor was not taken into account in assessing the agents because it was assumed they had little knowledge of or control over the supplier’s shipments. Now that the agents have accurate information about OxyVinyls’ production and shipping schedules, they are held accountable for the availability as well as the price of the materials they buy.

Geon has recently gone a step further, integrating its processes with those of its customers. It has put sensors into some of its major buyers’ warehouses so that it always knows how much of its compounds a customer has in stock. When inventories decline to an agreed upon level, Geon automatically sends replenishments, cutting out many traditional stock checking and ordering activities.

Through Geon’s efforts, the processes of three different companies- the customer’s procurement processes, Geon’s order-fulfillment and procurement processes, and OxyVinyls’ order fulfillment process- have been integrated. They are now all managed as a single process, without regard to corporate boundaries and with much less friction, overhead and error. The payoffs have been dramatic, Geon’s 8% error rate in placing orders has gone to 0%, its order fulfillment cycle time has fallen back to its earlier level, and its inventories have declined 15%.

Its labor costs have also fallen, because non-value-adding work has been eliminated. More important, the company has been able to reassign many of its people to jobs in which they enable Geon to better fulfill its new strategy of focusing on high-value-added activities.

Relocating Work of a Company:

It may be tempting to look at Geon’s story simply as an illustration of the power of using the Internet to connect disparate information systems. But while that’s an accurate technological description, it misses the bigger point- Separate processes in separate companies have been connected and combined and now work as one. New technologies may be the glue, but the more important innovation is the change in the way people think and work. Rather than seeing business processes as ending at the edges of their companies, Geon and its partners now see them – and manage them-as they truly are- chains of activities that are performed by different organizations.

Although the concept of supply chain integration has been around for some time now, companies have had trouble making it a reality. It most cases, that’s because they’ve viewed it as merely a technological challenge rater than as what it really is- a process and management challenge. Once you adopt this broader view, you can quickly cut a lot of costs and waste from your existing operations. But you can do much more as well – you can discover new and better ways to work. You can begin to shift activities across corporate boundaries. If your company, for instance, happens to be in a better position today to do some work that my company has traditionally done, then you should do it- even if that work is “officially” my responsibility. The increased costs you incur doing the work will be more than offset by the benefits of improving the processes as a whole, benefits that will accrue to both of us.

IBM is now using this approach to manage customers’ order, In 1998, IBM estimated that it spent $233 to handle each order it received, much of which went to “order management” – getting the order in, making sure that it was at the appropriate price, answering customers’ questions about payment status, and so on. The overhead could be traced in large part to the wall that separated IBM from its customers. The company had long required that all customer interactions be mediated by an IBM employee- usually, a sales rep.

By removing this requirement, IBM has been able to integrate its fulfillment process with its customer’s procurement processes and redesign the unified process to work much more efficiently and flexibly. Now customers can do for themselves much of the work that IBM had previously done for them, with greater convenience and lower costs. With the new process and systems, customers can enter their own orders into IBM’s computer system and can check the status of their orders. IBM wins because its costs are lower; the customer win because they get the work done correctly at a time of their choosing with IBM’s gatekeepers. There are other benefits as well.

On important set of customers-value-adding resellers-has been able to reduce its inventories of IBM equipment by more than 30%. Since the resellers can get orders into IBM’s process more quickly and can find out when the orders will actually be filed, they get by with less stock on hand. That makes them happier customers, which IBM knows makes them more loyal customers. It also reduces channel inventor, tempering the risk that IBM will be harmed by sudden shifts in demand.

At the same time, IBM is now doing some work that customers used to have to do for themselves. The large corporations that buy from IBM typically standardize the computers they use, requiring all employees to order the same configuration. But in practice, many people get the specifications wrong or make other mistakes in ordering; it was not uncommon for IBM to see an error rate of more than 50% in orders from corporate customers. In effect, the customer’s ordering process was defective (in not screening out inappropriate orders), and IBM had to compensate for the failure.

Now, IBM has taken over the work of vetting customer orders. The customer provides IBM with a complete description of the approved configuration. IBM then limits the customer’s employees to ordering only that configuration. Both IBM and the customer benefit because they have to spend less time cleaning up the mess that results from inaccurate orders.

Simplifying Supply Chains of a Company:

Another high-tech company, Hewlett-Packard, has taken an even more aggressive approach to restructuring work in cross-company processes-in a way that is reshaping the economics of its supply chain for computer monitors. A typical purchaser of an HP monitor probably has no idea how many companies are involved in production it. Like most computer makers, HP has outsourced much of it’ manufacturing to contract producers, such as Solectron and Celestica.

The contract manufacturer buys the case for the monitor from an injection molder, which the case for the monitor from an injection molder, which acquires the material used to make the case from a plastic compounded (Geon is an example), which in turn buys the material for the compound from a resin maker. This supply chain is fairly easy to describe, but, until recently, it was almost impossible to manage.

For one thing, the suppliers at the opposite end of the chain from HP had no idea how many monitors HP would actually need; they often didn’t even know that HP was the ultimate destination for their resin or compound. Consequently, each had to carry a lot of inventory in case an HP order came barreling down the chain.

In many cases, the inventory that they did carry ended up not being what HP needed at the moment. When that happened. HP was sometimes unable to deliver an order when the customer needed it, forcing the customer to go elsewhere. Disputes between upstream suppliers could also lead to unexpected delivery delays that might disrupt HP’s ability to fulfill orders. Such situations meant lost revenue for everyone in the supply chain.

Another complexity was the volatility in order specifications. In theory, once HP placed an order, its suppliers should have been ready to roll. But the reality of the computer business is that nothing stays fixed for long. On average, an order for a batch of computer monitor changes four times before it is completely filled, usually in response to shift in marketplace demand. Quantity, delivery date, and color are just a few of the variables that are routinely altered.

The disparity in scale between the participants in this supply chain complicated matters further.

HP and its resin supplier are giant companies, and the contract manufacturers are fairly substantial as well. But most injection molders are relatively small outfits, as are most compounders. So every HP order for monitor cases was usually split among many compounders, each of which bought resin in relatively small volumes-and, consequently, at relatively high prices- from the resin maker.

HP’s potential purchasing clout, in other words, dissipate at each step in the chain that separated it from its ultimate supplier. Because it was shielded from the suppliers of compounds and resins, HP also lacked the ability to track their quality and delivery performance and their prices and terms, and it rarely heard their ideas for enhancing products and processes.

An army of people, dispersed among the different companies and using a host of unrelated information systems, was required to hold this cumbersome set of processes together at great cost. Recognizing the problem, HP in 1999 resolved to integrate the entire supply chain and coordinate the unified process. The company assumed responsibility for ensuring that all parties work together, share information, and operate in a way that guarantees the lowest costs and the highest levels of availability throughout the chain.

The hub of the newly integrated process is computer system that HP set up to share information among all the participants. HP posts its demand forecasts and revisions for its partners to use in their own forecasting. The partners post their plans and schedules and used the system to communicate with their own suppliers and customers, exchanging electronic orders, acknowledgments, and invoices, HP’s procurement staff manages the entire process, monitoring the performance of the upstream suppliers, helping to resolving disputes relating to payments, and keeping supply and demand in balance. The company’s purchasing agents, once narrowly focused on terms and conditions, have seen their jobs broaden considerably.

The integrated process has dramatically enhanced the performance of the supply chain. Today, any kind of change to an HP order ripples through the chain instantaneously, allowing everyone to react quickly. And if any problem crops up that threatens HP’s ability to meet its forecasts, HP learns of it early enough to make other plans. Because it coordinates the entire process, HP can also order all its required resin directly from the resin supplier. It provides the resin maker with an aggregate order, and it receives a single bill at a uniform, considerable lower contract price. The resin maker benefits from this new relationship as well; it gets the simplicity and security of dealing with one large customer rather than a host of small ones.

Streamlining the supply process has helped every participant, but HP has perhaps profited most. In the first implementation of this process, the price HP pays for its resins has gone down as much as 5%, the number of people it requires to manage the supply chain has cut in half, and the time it takes to fill an order for a computer monitor has dropped 25%. Best of all, HP estimates that it is increasing sales in the area in which it has implemented this newly integrated process by 2%. These are sales that the company had previously lost because it could not deliver the right product at the right time. HP no longer has to commit the mortal sin of turning customers away.

Coordination and Collaboration in a Company:

The examples I’ve described so far center on the management of supply chains. That shouldn’t be a surprise. Supply chain problems are highly disruptive- and costly- to companies, and fixing them delivers a big, immediate payoff. So companies have tended to focus their initial efforts in streamlining cross-company processes on the supply chain. But tantalizing opportunities in other area are now starting to appear. The next major wave is likely to be the integration of product-development processes.

A company, its suppliers, and even its customers will be to share information and activities to speed the design of a product and raise the odds of its success in the market. Suppliers, for example, will be able to being developing components before an overall product design is complete, and they will also be able to provide early feedback as to whether components can be produced within specified cost and time constraints.

Customers, for their part, will be able to review the product as it evolves and provide input on how it meets their needs. In a very real sense, this kind of collaborative product development will be the multi company analogue of concurrent engineering, which has transformed internal product development over the past 15 years.

On a more profound level, we’re beginning to see examples of an entirely new kind of process collaboration, which promises to change the way we think and even talk about business. The traditional vocabulary of corporate relationships is meager- If you sell me something, I am your customer, and you are my supplier; if another company tries to sell me the same thing, it is your competitor. And that’s about it, because those were the only relationships the made any difference to us.

But what if you and I are both buying the same product or service from the same supplier? In the past, it was unlikely that either of us would discover that we had such a relationship, and even if we did, the information would have been of little, if any, value. Consequently, we had no term to describe it. Similarly, what if you and I sell different products, but to the same customer? We are not competitors, but what are we? In the past, we didn’t care. Now, we should.

Consider the recent experience of General Mills, a giant in the business of customer package goods, with brands ranging from cheerios to Yoplait. From years, margins have been falling for customer packaged goods as distributions channels have consolidate and consumers have become more selective. Through the 1990s, General Mills led the industry is squeezing costs out of its supply chain.

Through increased purchasing effectiveness, manufacturing productivity, and distribution efficiencies, General Mills’ cost per case of product declined by a remarkable 10% during the decade. But as a new decade dawned, the company’s leaders realized they would have to move beyond the confines to their linear supply chain in order to find new cost-savings opportunities. Among their first ideas was a radical new approach to the distribution of their refrigerated products, like yogurt.

As businesses, refrigerated goods and dry goods have very different characteristics. The top seven dry-gods manufacturers together account for nearly 40% of total supermarket sales in that category.

Each of the manufacturers has enough sales to efficiently operate its own distribution network, including warehouses and trucks. In the refrigerated category, however, the top seven players represent less than 15% of total supermarket sales, and near all lack the sale needed for a highly efficient, dedicated distribution network, Nonetheless, each company maintains one, and, unsurprisingly, each suffers from sub-optimal productivity as a result.

When a refrigerated truck laden with Yoplait, for example, leaves a General Mills warehouse headed for local supermarkets, it is often carrying less than a full load. Even more often, it is carrying orders for several supermarkets, requiring it to make many stops, if the truck is delayed in traffic or encounters a snafu at one of its early stops, it may not make it to the final supermarket on its route that day. If that supermarket has just run an ad promoting a special on Yoplait, it will have to deal with angry customers, and General Mills will face a frustrated supermarket in addition to lost sales.

General Mills realized that it could address the problem by integrating its distribution process with another company’s. It found the perfect partner in Land O’Lakes, a large produce of butter and margarine. Land O’ lakes products do not compete with those of General Mills, but they have the some customers. The two companies agreed to combine their distribution networks, giving them the scale necessary for high efficiency. Today, General Mills’s yogurt and Land O’ lakes butter ride in the same trucks on their way to the same supermarkets.

When land O’Lakes receives an order, it ships the goods to a General Mills facility, where they are immediately loaded onto a truck containing General Mills yogurt headed for the same customer. Or, if the customer chooses to pick up the goods itself, the orders are stored together in a special section of a General Mills warehouse.

With the combined process, General Mills’ trucks go out much fuller than before, and since they’re delivering more products to each supermarket, they make fewer stops and suffer fewer delays. The arrangement has been so successful, in terms of both lower costs and higher customer satisfaction that the two manufacturers are now planning to integrate their order taking and billing processes as well. They are also working together to create incentives for customers to order larger combined amounts from the tow companies, which will result in even greater transport savings.

General Mills and Land O’Lakes are noncompetitive suppliers – what I’ve come to call co supplier- to the same customers, and it is to their mutual advantage to find ways to work to work together. The potential for such relationships has always existed, but in the past it was difficult, if not impossible, to make them work.

There was simply no efficient means of sharing information quickly and accurately enough. Manually coordinating two companies’ deliveries through a shared distribution network would quickly have turned into a logistical nightmare. But with the Internet and associated communication technologies, these kinds of business relationships suddenly become feasible, opening up new opportunities for creative companies.

Indeed, anywhere that different companies use similar resources, there are opportunities for reducing costs through sharing, For instance, a recent study by a group of manufacturers showed that they collectively owned about 30 million squire feet of warehouse facilities in the greater Chicago area, but only 82 % of the space was being used. By sharing warehouse space with one another, these companies envision eliminating the waste and sharing the benefits. The U.S. trucking fleet is plagued by similar inefficiencies. Because shippers plan their deliveries independently, they often have to pay for derivers to move empty trucks from the end point of one trip to the start of the next one. At any given time, 20% of the nation’s trucks are traveling empty, raising costs for both shippers and truckers. Some companies, however, are now starting to merge their logistics processes. By planning shipments and contracting for trucks together, they’re saving money for themselves and their carriers.

Structuring the Project of a Company:

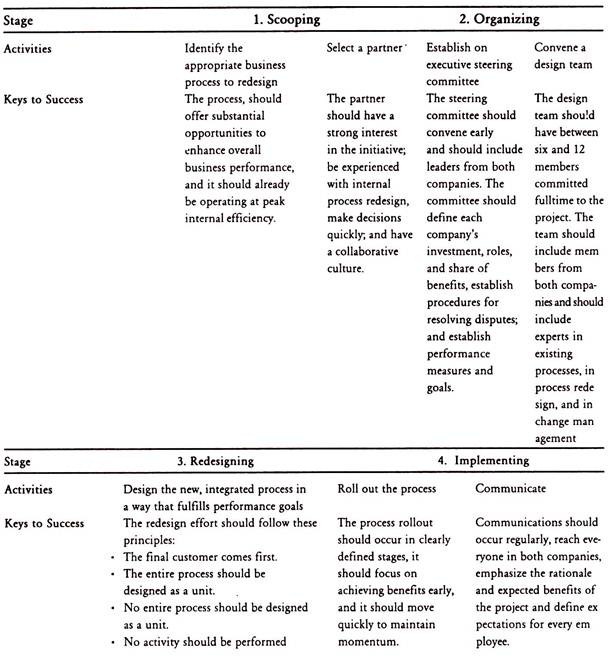

Companies that have redesigned their internal processes know that success requires a rigorous, structured approach. The same is true for streamlining cross-company processes, but here the challenges are even greater. No matter how tough it is to get different departments to work together, getting different companies to collaborate is even harder.

I have found that it’s best to structure the project into four major stages:

1. Scoping,

2. Organizing,

3. Redesigning, and

4. Implementing.

1. Scoping:

First, you have to set your sights on the right targets. Start by identifying the intercompany process that offers the greatest opportunity for improving your overall business performance, whether it’s a supply chain, product development, distribution, or other process. Typically you’ll want to select a process that you’ve already brought to peak internal efficiency; it makes little sense to merge processes that still harbor inefficiencies.

The choice of the partner you’ll work with may be the most important decision you’ll make. Obviously, the partner needs to be a company that is likely to have an interest in working with you to streamline to process, but that is not nearly enough. You need to evaluate the other company’s technical competence and cultural fit for doing intercompany process redesign.

Does it have significant experience with transforming its internal processes? It should, since a cross-company process is a risky place to learn the basics. Can the company make decisions quickly? If not, the effort will never yield fruit. Does it have a collaborative style A focus on the short term rather than trust, a search for one-sided advantage rather than mutual benefit- any of these will doom the initiative.

Steps to super efficiency:

Streamlining cross- company business processes is the next great frontier for reducing costs, enhancing quality, and speeding operations. But the leap to super efficiency requires a rigorous, structure approach such as the one described here.

2. Organizing:

The operating and cultural consequences of intercompany process redesign are so far-reaching that strong executive leadership is needed from the outset. An executive steering committee, comprising leaders from both companies, should be convened very early. One of its first responsibilities should be to define the rules of engagement. What will each party invest in this effort? How will benefits be shared? How will conflicts and disputes be resolved? Collaboration on processes is fairly unfamiliar territory for most organizations, and setting ground rules at the start will avoid a lot of misunderstanding later. The steering committee also needs to decide which performance measures (such as cycle times, transaction costs, or inventory levels) will be targeted for improvement and to establish specific, quantified goals.

While the steering committee sponsors the process redesign, it does not actually do it. That is the role of the design team. The design team should include people from both companies, and its core me members should be experts in the existing process, people skilled in process redesign, and specialists in technology and change management. Too large a team is unwieldy, and too small a group lacks the critical mass to get anything done; typically, six to 12 people is the right size. As a rule, all members should be assigned full time to the project. Speed is of the essence here, and part- timers tend to be so distracted by other responsibilities that they move glacially, if at all.

3. Redesigning:

During the redesign stage, the team members roll up their sleeves, take the existing process apart, and reassemble it to achieve the performance goals.

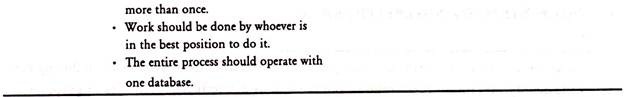

Here are some principles that the team should follow in coming up with the new design:

i. The final customer comes first:

Both companies need to submerge their narrower goals in service to a higher one- meeting the needs of the customer whom they work together to serve. Participants must that a company they have always considered a customer may, in fact, be merely a collaborator in serving the ultimate customer.

ii. The entire process should be designed as a unit:

That many sound obvious, but it’s an easy point to lose sight of. Make sure all members stay focused on the big picture; otherwise, they may begin to address the processing in pieces rather than as a whole.

iii. Work should be done by whoever is in the best position to do it:

IBM enforces its customers’ computer standards; HP buys resin for its suppliers’ suppliers’ suppliers. It defeats the purpose of a collaborative to attempt to be self-sufficient. Do what you do best, and let others do the same.

iv. The entire process should operate with one database:

When everyone shares the same version of all the information, reconciliation tasks can be eliminated and assets can be deployed precisely and efficiently.

Working on an interdisciplinary process design team is an unfamiliar experience for almost everyone; when one’s teammates come from another company and not just another department, the unfamiliarity increases dramatically. Frequently, people from one company will lack even the most basic understanding of the operations and concerns of the other. Team members therefore need to develop an appreciation for the challenges facing the other company. They must also learn that they are not representing their company’s interests but those of the process as a whole.

4. Implementing:

Once the process has been redesigned, it must be rolled out. Two principles are critical to success in this stage. The first is “think big, start small, move fast.” Trying to implement a radically new process in one step is almost always a recipe for disaster. Any intercompany working relationship will be tenuous until real results are achieved, and the longer it takes to reach that milestone, the greater the risk that the whole thing will unravel. Consequently, the entire effort must be conducted with an eye on the clock. The redesign team should develop its vision for the process being revamped in weeks, not months, and it should organize the implementation so as to deliver tangible results quickly.

The second principle is “communicate relentlessly.” Redesigning an intercompany process not only changes people’s job, it also changes how they think about and relate to other companies. Information sharing, openness, and trust need to replace information hoarding, suspicion, and downright hostility. Without constant reminders of the rationale for the redesign, the benefits that will accrue to each company, and the expectations for every employee, the needed cultural change simply will not occur.

It’s natural for a company to get nervous about tearing down the walls that enclose its organization. The act goes against many long-held notions of corporate identity and strategy. But most companies were nervous about breaking down the walls between their internal departments and business units, too. Some even delayed the effort- and they have spent the last decade playing catch-up with their competitors. Streamlining intercompany processes isn’t just an interesting idea; it’s the next frontier of efficiency. Right now, it’s the best way to develop a performance advantage over your competitors or to prevent them from developing one over you.