This article throws light upon the six important approaches to organisation and departmentation. The approaches are: 1. Functional Departmentation 2. Product Departmentation 3. Territorial (or Location) Departmentation 4. Customer Departmentation 5. Process (or Equipment) Departmentation 6. Project Departmentation.

Approach # 1. Functional Departmentation:

Probably the most common approach to organising is functional departmentation. An organisation that exhibits functional departmentation has chosen to group together those jobs wherein employees perform the same or similar activities.

It groups together common functions or similar activities under the major headings that nearly every business has in common — finance, production, marketing and personnel—to form an organisational unit.

The word ‘function’ here is used to mean organisational functions such as finance and production rather than basic managerial functions such as planning or decision-making. These are the basic functions of the business, and the entire organisation would be divided into these major areas.

Thus all individuals performing similar functions are grouped together, such as all sales personnel, all accounting personnel, all secretarial personnel, all computer programmers and so on.

In general functional departmentation is used at the top management level in dividing the four major business functions — production, marketing (sales), personnel and finance. However, functional departmentalisation may occur at any level of the organisation and is generally found very near the top.

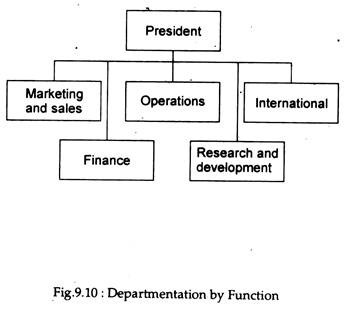

Fig. 9.10 shows how these four major functional areas could be organized. Each of the four major functions is subdivided into three major parts.

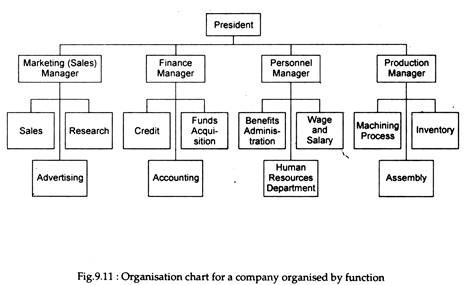

Another, and a more simple, example of a firm that is departmentalised by function appears in Fig. 9.11. This company. Beauty Products manufacture and markets various types of cosmetics, toiletries and fragrances. One set of activities for this kind of organisation involves the actual manufacturing of the products.

When grouped together these activities are called operations. For example, the activities associated with advertising, promotion and selling are grouped together as marketing and sales. Finance involves the management of the firm’s financial resources, and new product development fits into the research and development (R&D) department.

Finally, activities concerned with overseas business opportunities are grouped together in the international division.

Relevance:

Functional departmentalisation is most common in smaller organisations, because it is very compatible with a relatively high level of work specialisation. A functional form of organisation emerges in response to increased levels of specialisation.

Advantages:

The functional approach is a logical way to organize for most businesses. What each employee or unit does or will be becomes the basis of organisation. Thus this approach minimizes costly duplications of manpower and equipment and/or helps to avoid overlap in the execution of basic business activities.

For instance, having all computers and computer personnel in one department is less expensive than allowing several departments to have and supervise their own computer equipment and personnel.

Secondly, under this approach lines are clearly drawn between the functional areas. The functional organisation simplifies training because it provides for occupational specialization. For example, production or marketing can concentrate on training people in their speciality areas. Thus this approach creates efficiency through the principles of specialization.

Thirdly, the functional approach centralizes the organisation’s expertise, and permits tighter top-management control of the functions.

Three other advantages are the following:

(1) each department can be staffed by experts in that functional area,

(2) supervisor is facilitated because an individual manager needs to be familiar with only a relatively narrow set of skills, and

(3) it is, therefore, easier to coordinate various activities within each department.

Disadvantages:

However, as an organisation grows in size, several disadvantages of functional departmentation may emerge:

1. Firstly, responsibility for total performance rests only at the top, and, since each manager oversees only a narrow function, the training of managers to take over the top position is limited. This problem is sought to be tackled by transferring managers so that they became ’rounded’, with experience in several functional areas.

2. Secondly, because personnel are separated from one another, it is difficult to achieve their understanding and concern for the speciality areas outside their own. This narrowness of viewpoint may create communication problems and lack of co-operation among the functional areas which can escalate to hostility.

There could emerge a ‘production position’ and a ‘marketing position’ quite separated from each other. If carried to the extreme, this narrow view can result in a speciality area placing its own welfare before that of the organisation as a whole.

3. Thirdly, it fails to develop generalists in the management area. The narrow view-point and specialised training develop staff members who are experts in their own functional areas. But there is lack of understanding of the interrelationship and dependency of all functions. The lack of generalism and potential internal rivalry that threatens a functional approach to organisation makes growth of the organisation as a system difficult.

4. Fourthly, co-ordination between and among functions becomes complex and more difficult as the organisation grows in size and scope.

Other disadvantages are the following:

5. Decision making tends to become slower and more bureaucratic.

6. Employees may begin to concentrate too narrowly on their own units and lose sight of the total organisation system.

7. Accountability and performance become increasingly difficult to monitor (for example, it may be virtually impossible to determine whether a new product’s failure is due to production deficiencies or to a poor marketing campaign).

8. Finally, individuals identify themselves with their narrow functional responsibilities, causing subgroup loyalties, identification and ‘tunnel vision’ thinking.

To sum up, functional departmentation is common and generally logical for small organisations. With the growth of the organisation, however, the problem that functional departmentation can engender begin to offset the advantages it offers. An alternative type of departmentation — which is most common in large organisations and especially in those with a large number of products or product line — is product departmentation.

Approach # 2. Product Departmentation:

At some stage of organisational development, the problems of co-ordination under a functional approach becomes really complex and extremely cumbersome, especially when rapid, timely decisions must be made. Since the functional approach is slow and cumbersome, some products that are supposed to have the most potential may fail to receive the attention they deserve.

And no single individual can be make accountable for the performance of a given product line. To resolve the dilemma many organisations shift to smaller, more semi-autonomous mini-organisations built around specific products, each with its own functional capabilities. This is the essence of product departmentation.

In short, product departmentation is the grouping and arranging of activities around products or product groups. The rationale for such an approach is that, when the number of products or product groups are beginning to get larger, the products are also likely to become more diverse.

A single firm, for example, may be manufacturing a wide range of products — from bus chassis to instant coffee (as is true of the Tata group). The marketing, financial, production, human resources and R&D activities associated with bus chassis are likely to be much different from those associated with consumer goods.

Thus, it is more logical and more feasible to group the specialised activities for each product line than to insist, say, that one functional department market with bus chassis and without coffee.

This type of organisation pattern has to be considered when attention, energy and efforts need to be focused on an organisation’s particular products. The product line approach is called for when each product requires a unique strategy or production process or distribution system or capital sources.

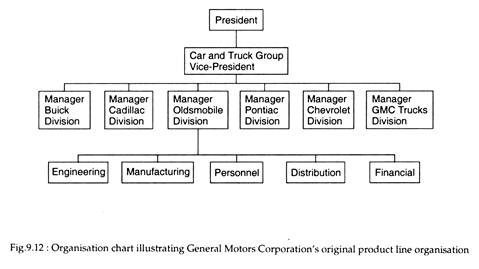

Or product departmentation could result if top management tries to focus the strategy and talents of individuals or areas of expertise. The most glaring example of this is the departmentation to General Motors Corporation (U.S.A.) Fig. 9.12 illustrates the product line approach in the context General Motors.

A Case Example: Organisation Chart of General Motors:

From the very beginning General Motors has been organised by product line. Fig.9.12 shows the original position of the company. Originally the company was organized under the separate product line divisions of Chevrolet, Buick, Oldsmobile, Cadillac, Pontiac, G.M.C. Truck, and so on.

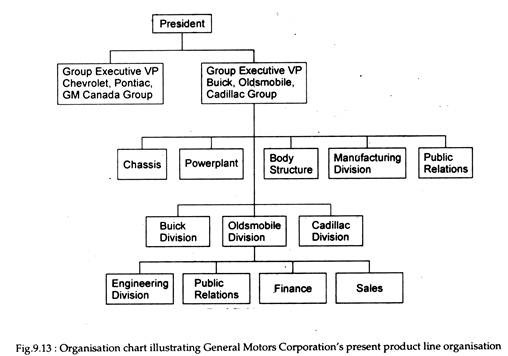

Each product line division had three functional divisions: manufacturing, finance and distribution. In an effort to specialize on the small car field, G.M. re-organised its structure. While maintaining the product departmentation, it now has two operating divisions: the Chevrole-Pontiac division for small cars and the Buick-Oldsmobile-Cadillac division for larger models (Fig. 9.13).

A related point may also be noted here. The strategic business unit (SBU) approach to strategy revolves around a product view of departmentation. This means that each SBU can be viewed as a department responsible for a particular product or product group.

In this context, one may cite the example of Oki Electric Industry Company of Japan which adopted a SBU structure. In 1978, the company created 15 departments or SBUs centering on such high-profit products as computer terminal peripherals and integrated circuits. Within three years, the company’s sales had increased by 12% and its profits by 28% as a result of product departmentation.

Advantages:

Product departmentalisation works well in the exploration and generation of petroleum products, in the production of textbooks or in the manufacture of electronics, because it allows a company to concentrate its research speciality on specific and related projects and problems.

Such departmentation confers six major advantages:

1. Attention can be directed toward specific product lines or services.

2. Co-ordination of functions at the product division level is improved. Activities associated with one product or product group can be easily integrated and coordinated.

3. The speed and effectiveness of decision-making are enhanced.

4. Performance of individual products or product groups can be assessed more easily and objectively, thereby improving the accountability of departments for the results of their activities.

5. Profit responsibility can be better placed. Since each department is a separate profit center, each department head is responsible for its profit performance.

6. It becomes easier for the organisation to develop several executives who have broad managerial experience in running a total entity.

7. It allows a scale force to sell complementary products to a consistent group of buyers or purchasing agents.

8. Competition occurs within the organisation between product managers, sales managers, and others to out perform one another and to get a large share of the assets and resources of the organisation.

Disadvantages:

1. The major disadvantage of product departmentation is that it requires more personnel and material resources.

2. If carried to its extreme, this type of competition can be destructive.

3. Unnecessary duplication of resources and equipment or duplication of business functions within each product line may result. This is both time-consuming and cost-raising. Administration costs rise, because each department must have it own functional specialists such as, marketing researchers and financial analysts.

4. Each product needs marketing, finance, personnel and production operations, which may be so specialised that they are unable to serve more than one product line or division.

5. Managers in each department tend to focus on their own product or product group to the exclusion of the rest of the organisation.

6. Top management shares a greater responsibility (burden) of establishing effective co-ordination and control. It is desirable for top management to utilise staff support to create and oversee policies that guide and limit the range of actions taken by its divisions.

Approach # 3. Territorial (or Location) Departmentation:

Territorial departmentation is grouping activities according to the places where operations are located and makes sense in various marketing, financial, and production companies. A marketing organisation may group its sales activities into Eastern, Western, Northern and Southern regions of India.

Commercial banks often group their lending and other activities in a similar fashion. This type of departmentalisation is used frequently in the function or product departmentation.

The advantages and disadvantages of territorial departmentation are similar to those of product departmentation. This approach furnishes a training ground to develop general management abilities. Managers are responsible for the activities in that geographical area. There is also better co-ordination of activities in a specific area.

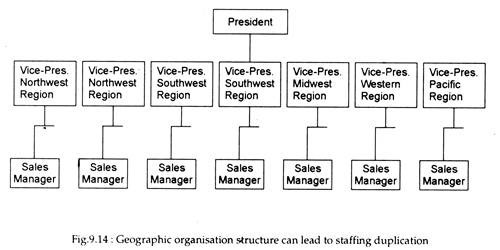

The cost of personnel and facilities of this type of departmentation is high. When a company decides to expand geographically, it automatically incurs cost through duplication of personnel positions and additional building sites. To be more specific, the functional structure requires one sales manager.

The territorial approach using 7 separate geographical sales regions staffed by management personnel may require seven sales managers. This organisational dilemma is illustrated in Fig. 9.14.

In short, such a grouping enables a division to focus on the unique needs of its area, but it requires top management co-ordination and control of each region.

Advantages and Disadvantages:

The most important advantage to be secured from this form of departmentation is that it enables the organisation to respond easily to unique customer and environmental characteristics in the various regions. On the other hand, a large administrative staff may be required, if the organisation is to keep track of units in scattered locations.

Approach # 4. Customer Departmentation:

Customer departmentation is grouping in such a way that they focus on a given use of the product or service. This type of departmentation is used primarily in grouping sales or service activities.

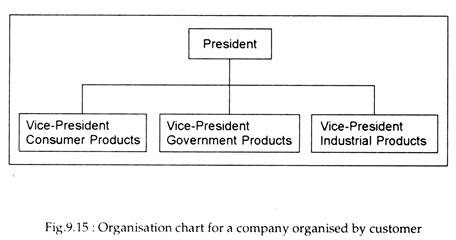

Under customer departmentalisation, the organisation structures its activities so as to respond to and interact with specific customers or customer groups.

Organisation around groups of customers makes sense when the customers are distinct enough in their demands, preferences, and needs to justify it. Fig.9.15 shows a customer structure. Just how far an organisation should carry out its customer approach depends on its internal decisions about how to serve itself and its customers.

Customers may simply be grouped as government and others, or as wholesale and retail. This approach may be chosen for some but not all the customers.

Advantages and Disadvantages:

The major advantage of this approach is adaptability to a particular clientele. Customer departmentalisation allows the organisation to use skilled specialists to deal with unique customers or customer groups. The disadvantages are difficulty of co-ordination, under utilisation of resources, and competition among managers for special concessions for their own customers.

To be more specific, if the decision is made to use this approach with only some of a firm’s customers, there will be difficulty in coordinating the customer-based department with departments organized on other patterns. The managers of the customer-structured departments may constantly be in need of special treatment for their particular problems.

There is also the possibility of over specialisation: the facilities and personnel may become so specialised to solve the needs of their customers that they cannot be used for any other purpose — with the result of under utilisation. Finally, customer departmentation requires a fairly large administrative staff to integrate the activities of the various departments.

Approach # 5. Process (or Equipment) Departmentation:

Process departmentation is simply a grouping of activities that focuses on production processes or equipment. It is usually found in manufacturing.

A manufacturing plant’s activities may be grouped into drilling, grinding, welding, assembling and finishing departments. This approach is advantageous when the machines or equipment used require special operating skills or are of such large capacity that to be used economically (i.e., with the maximum possible efficiency) they must be used all the time (so that cost per unit is minimised).

The Hybrids: Project and Matrix Departmentation:

The project and matrix forms of organisation usually evolve from one or more of the other types of departmentation and are, therefore, hybrid in nature.

For a giant project such as the building of a prototype for a supersonic aircraft — the traditional approaches to organisation, discussed so far, do not easily provide the flexibility to handle such complex assignments, which involve expertise from numerous functional areas of the organisation.

The completion of such a project requires close, integrated work between and among numerous functional specialities. In truth, both project and matrix forms of departmentation involve ways to bring together organisational personnel from several specialities to complete finitely durable projects (i.e., limited-life tasks).

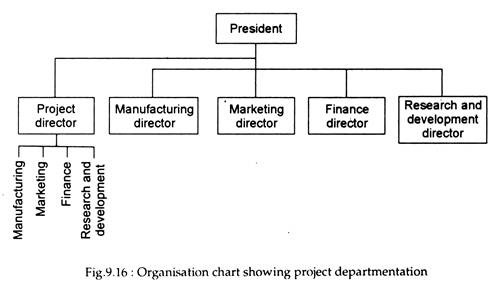

Approach # 6. Project Departmentation:

Project departmentation involves the formation of independent, finite life teams of specialists necessary to achieve a specific goal. As shown, a project director is given line authority over the team members during the life of the project.

For instance, in a manufacturing firm a production specialist, a mechanical engineer, and a chemist might be assigned to a project manager to complete a pollution control project team, with full authority over its members for the specific project activity.

A variation of this approach is for a project manager to have less than full authority over members who may be assigned only part time to the project. Thus, for instance, a design engineer may be involved in a certain special project for half the time, with the remaining half of his time devoted to normal work assignments within the design department.

This arrangement may create a number of problems. Prima facie, the project managers may have an ‘authority gap’ because they do not possess authority to reward or promote their personnel. Since their responsibility for results outweighs their authority, these managers must find ways of increasing their authority and minimizing (if not closing) this gap.

Once the project is completed, the team is dissolved, and team members go back to their original functional bases in the organisation, perhaps to be reassigned full or part time to another external project or to be assigned to more permanent work within their functional departments.

Matrix Design or Departmentalisation:

The matrix design is often used to handle the information- processing need of an organisation. But it goes far beyond simply establishing lateral relationship. Indeed, it involves creating a totally new kind of organisational structure.

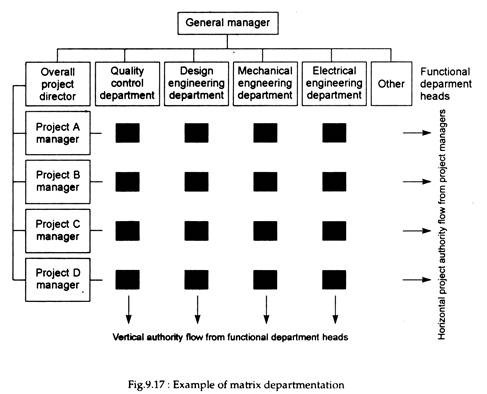

Matrix departmentation is similar to project departmentation with one major exception. Under this form the project manager does not have line authority over the project team members. Rather, the project manager organisation is superimposed on the various functional departments, giving the impression of a ‘matrix’.

Essentially a matrix design is based upon two types of departmentation, discussed earlier. First, it is based on departmentation by shared tasks or common expertise, in general, on functional department. Second, it is based on department by project or product. Employees in a matrix are simultaneously members of a function (e.g., engineering) and of a project team.

As such, they have two “bosses” — a functional boss and a project boss. The presence of two intersecting lines of authority is the hallmark of a matrix design.

A matrix organisation pattern is a design showing a wonderful (blend) of the functional organisation structure. Applications of the matrix approach are usually found in high-technology, project- based industries such as aerospace, government contracting, consulting, and research and development business.

The easiest way to visualise a matrix design is to imagine project-based department superimposed on an existing functional structure. Such an arrangement is shown in Fig.9.17.

Here the leader of Project A is responsible for completing the assigned project that may require the work of a quality control specialist, a testing and quality assurance specialist, a research and development expert and a design engineer.

Although only four functional departments are shown in this example the matrix approach is flexible enough to cover many more and the various projects — B, C, and D — could each have personnel from varying functional departments assigned to the project.

In other words, during the course of the project, the technical team specialists have access to and can use the resources of their functional departments. This ongoing relationship of function and project, along with the lines of authority (downward from functional manager to technical representative and across from project supervisor to technical representative) compose a grid, which is called a matrix.

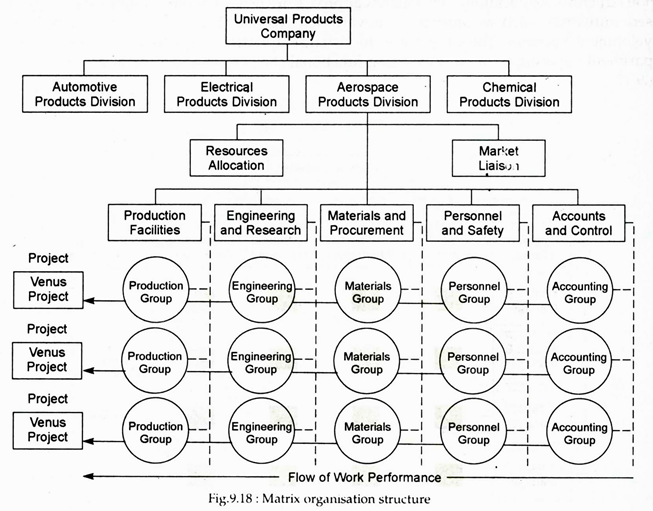

Fig. 9.18 presents another matrix organisation structure for an aerospace project. The project groups or teams are assigned to designate projects or programmes. The functional departments — production, materials, personnel, engineering and accounts — are permanent components of the organisation.

The various project teams — Venus, Mars, and Saturn — are created as and when the need arises and are dispensed with as soon as the project is completed.

Members of the Venus project team are selected from the functional departments and are supervised during the duration of the project by the Venus project manager.

An important point about the matrix organisation is that it provides a hierarchy that responds quickly to changes in technology. Hence it is typically found in technically-oriented organisations such as Boeing, General Electric, etc., in which scientists, engineers, or technical specialists work on sophisticated projects or programmes. It is also used by companies with complex construction projects.

Under the system, team members’ functional departments maintain personnel files, supervise administrative details, and assemble performance reports while their members are on different assignments. Many major U.S. organisations have adopted the matrix form of organisational design.

Advantages:

There are both advantages and disadvantages associated with the matrix form of organisational design. In an ideal situation, however, the advantages seem to outweigh the disadvantages.

The major advantages of the matrix organisation are the following:

1. Minimum organisational conflict:

The matrix approach utilises the technical resources of an organisation by efficiently allocating the expertise where and when it is needed. So it is supposed to produce a co-ordinated effort because if focuses the functional expertise on a project, thus minimizing conflict between and among speciality areas.

2. Improved communication and co-ordination:

Secondly, the temporary project and matrix approaches permit open communication and co-ordination of activities between the relevant functional specialists.

3. Flexibility:

Finally, the flexibility of the two forms of departmentation enables the organisation to respond rapidly to change. In fact, the two approaches are essential in technologically oriented industries.

As Griffin has put it:

“One of the truly significant advantages of a matrix is its flexibility. Teams can be created, redefined and dissolved almost continuously, allowing the organisation to cope readily with uncertainty, instability and change.”

4. Management planning:

The matrix design gives top management a useful vehicle for decentralisation. Once the day-to-day operations have been delegated, top management cap devote more attention to such areas as long-range planning.

5. Personnel development:

Employees in a matrix organisation have considerable opportunity to learn new skills. This becomes possible due to their involvement in a variety of projects and from their interaction in the teams with experts from other areas.

6. Improved motivation and commitment:

Because the teams in a matrix organisation consist of specialists from different functional areas, each member assumes a major role in decision making. As a consequence, team members are likely to be highly motivated and committed to the organisation.

7. Cooperation:

Team members retain membership in their functional unit, so they can serve as a bridge between the functional unit and the team — enhancing cooperation.

8. Human resource development:

The matrix design also provides an efficient way for the organisation to take full advantage of its human resources. Because the same expert can be assigned to several different teams, unnecessary duplication of personnel is reduced.

Disadvantages:

Although a matrix structure is both flexible and efficient, it has certain limitations. Even in the most ideal situation, however, eight major problems associated with the matrix form of design can still be significant and should not be ignored:

1. Power and authority confession:

Employees may be uncertain about whom they are supposed to report to, especially if they are simultaneously assigned to a functional manager and several project managers. The real problem crops up when several bosses make conflicting demands on them.

The matter becomes really complicated when some managers see the matrix as a form of anarchy in which they are free to do anything they want. It is, however, possible to minimise these problems by explicitly defining all authority relationships.

2. Conflicts:

Additionally, there is likely to be conflicts in terms of loyalty: Specialists do serve more than one master. They are asked to go in several directions. This implies loss of specialization. They work directly for the functional manager and the project manager. This is likely to create a strain on project members, the project manager, and the functional departments.

3. Lack of clarity and coordination:

Another disadvantage of project and matrix departmentation relates to the lack of clarity and co-ordination in the assigned roles. This, in its turn, requires ‘facilitators’ to intervene and resolve clashes resulting from conflicting priorities.

This usually happens when individuals may be assigned part time to two or more project teams or remain part time in the functional department, while at the same time they remain partly associated with another project. This is likely to place strong demands on team members in terms of the relative time devoted to each project.

In a matrix structure, the head of the functional department normally takes decision on the members’ advancement and promotion and assigns them to their next project. These decisions are partly based on reports received from project managers for whom the persons have worked.

But functional specialists are often ‘caught in the middle’ in disputes and torn between loyalties to project managers and to their functional department heads.

4. Constant drift:

There are also the disadvantages associated with the temporary nature of assignments under the two forms of departmentation.

As L.C. Megginson rightly argues- “Psychologically, one may never feel that one had ‘roots’ while drifting from one project to other — perhaps unrelated — projects.”

5. Loss of personal ties:

The close personal ties formed while working on a project team may be severed by the project’s completion, in which case an individual’s reassignment requires a new set of working relationships with strangers.

6. Group problems:

Another set of problem is associated with the dynamics of group behaviour. As a general rule, groups take longer to make decisions, maybe dominated by a strong individual, and may compromise unnecessarily. They may also got bogged down in discussion and not focus on their primary objectives.

7. Costs:

A matrix design is expensive because more managers and staff may be needed. More time may also be required for coordinating task-related activities.

Conclusion:

No doubt, there are various disadvantages of the matrix form of organisational design. However, these can probably be offset by the advantages. It appears that in the future, as environmental uncertainty continues to increase, more and more organisations will consider the matrix design because of its inherent flexibility.

Departmentalisation by Time:

Another basis of organising work and related activities could be time. For example, when employees perform shift work each shift is headed by a supervisor. When an organisation operates on three shifts, each one will have a superintendent who reports to the plant manager and each shift will have its own functional departments.

Final Considerations:

Two final points about departmentation may be noted in this context. Firstly, departments are also known by different names such as division, units, sections and bureaus. At higher levels of organisation, departments are referred to as divisions. The basic point to note is that all the different labels represent groups or jobs that have been lumped together according to some unifying principle.

Secondly, almost any organisation is likely to employ multiple basis of departmentation, depending on level. At the top level, departmentalisation might be by-product. Each product division may be further subdivided into functional departments such as finance, marketing and production.

The marketing department of a division may have special units for different customer groups, and each customer department may have regional sales territories built on location. Finally, a plant in one of the product departments might operate three shifts and be departmentalised by time.

Another possibility for combining many forms of departmentation is the matrix form of organisation, which combines functional and product departmentation at the same level.