Here is an essay on the three main steps necessary to manage liquidity risk in banks especially written for school and banking students.

Essay # 1. Developing a Structure for Managing Liquidity Risk:

Sound liquidity risk management involves setting a strategy for the bank ensuring effective board and senior management oversight as well as operating under a sound process for measuring, monitoring and controlling liquidity risk.

Virtually every financial transactions or commitment has implications for a bank’s liquidity. Moreover, the transformation of illiquid into more liquid ones is a key activity of banks. Thus, a bank’s liquidity policies and liquidity management approach should form key elements of a bank’s general business strategy.

Understanding the context of liquidity management involves examining a bank’s managerial approach to funding and liquidity operations and its liquidity planning under alternative scenarios:

i. The liquidity strategy should set out the general approach the bank will have to liquidity including various quantitative and qualitative targets.

ii. The strategy should also address the bank’s goal of protecting financial strategy and the ability to withstand stressful events in the market place.

iii. It should enunciate specific policies on particular aspects of liquidity management like composition of assets and liabilities maintain cumulative gaps over certain period and approach to managing liquidity in different currencies and from one country to another.

iv. The strategy of managing liquidity risk should be communicated through-out the organisation. All business units within the bank that conduct activities having an impact on liquidity should be fully aware of the liquidity strategy and operate under the approved policies and procedures.

v. The Board should monitor the performance and liquidity risk profile of the bank and periodically review information that is timely and sufficiently detailed to allow them to understand and assess the liquidity risk facing the bank’s key portfolios and the bank as a whole.

vi. Bank should have a liquidity management structure in place to execute effectively the liquidity strategy, policies and procedures. The responsibility of managing the overall liquidity of the bank should be placed with a specific identified group within the bank. This might be in the form of an Asset Liability Committee comprised of senior management, the treasury function or a risk management department.

Treatment of Foreign Currencies:

For banks with an international presence, the treatment of assets and liabilities in multiple currencies adds a layer of complexity to liquidity management for two reasons.

First, banks are often less well- known to liability holders in foreign currency markets. In the event of market concerns, especially if they relate to a bank’s domestic operating environment, these liability holders may not be able to distinguish rumours from fact as well or as quickly as domestic currency customers.

Second, in the event of a disturbance, a bank may not always be able to mobilise domestic liquidity to meet foreign currency funding requirements.

Hence, when a bank conducts its business in multiple currencies, its management must make two key decisions.

a. First decision:

The first decision concerns management structure.

A Bank with funding requirements in foreign currencies will generally use one of three approaches:

i. It may completely centralise liquidity management (the head office managing liquidity for the whole bank in every currency).

ii. Alternatively, it may decentralise by assigning operating division’s responsibility for their own liquidity, but subject to limits imposed by the head office or frequent, routine reporting to the head office. For example, a non-European bank might assign its London office responsibility for the liquidity management for its European operations in all currencies.

iii. As a third approach, a bank may assign responsibility for liquidity in the home currency and for overall coordination to the home office, and responsibility for the bank’s global liquidity in each major foreign currency to the management of the foreign office in the country issuing that currency. For example, the treasurer in the Tokyo office of a non-Japanese bank could be responsible for the bank’s global liquidity needs in yen. All of these approaches, however, provide head office management with the opportunity to monitor and control worldwide liquidity.

b. Second decision:

The second decision concerns the liquidity strategy in each currency. In the ordinary course of business, a bank must decide how foreign currency funding needs will be met. To what extent, for example, will a bank fund foreign currency needs in domestic currency and convert the proceeds to foreign currency through the foreign exchange market or currency swaps?

How will a bank manage the associated risk if exchange markets cease to be available? A bank’s assessment will depend on the size of its funding needs, its access to foreign currency funding market, and its capacity to rely on off-balance-sheet instruments (e.g., standby lines of credit, swap facilities, etc.).

A bank must also develop a back-up liquidity strategy for circumstances in which its normal approach to funding foreign currency operations is disrupted. Such a strategy will call for drawing either on home currency sources and converting them to foreign currency through the exchange markets or drawing on back-up sources in particular foreign currencies.

For example, back-up liquidity for all currencies may be provided by the head office using the home currency, based on an assessment of the bank’s access to the foreign exchange market and the derivative markets under the conditions in which the original liquidity disturbance is likely to occur.

Alternatively, a bank’s management may decide that certain foreign currencies make up a sufficient part of its liquidity needs to warrant separate liquidity back-up. In that case, either the home office or the regional treasurer for each specific currency would develop a contingency strategy and negotiate liquidity back-up facilities for those currencies.

Essay # 2. Setting Tolerance Level and Limit for Liquidity Risk:

Bank’s management should set limits to ensure liquidity and these limits should be reviewed by supervisors.

Alternatively supervisors may set the limits. Limits could be set on the following:

1. The cumulative cash flow mismatches (i.e., the cumulative net funding requirement as a percentage of total liabilities) over particular periods – next day, next week, next fortnight, next month, next year. These mismatches should be calculated by taking a conservative view of marketability of liquid assets, with a discount to cover price volatility and any drop in price in the event of a forced sale, and should include likely outflows as a result of draw-down of commitments, etc.

2. Liquid assets as a percentage of short-term liabilities. The assets included in this category should be those which are highly liquid, i.e., only those which are judged to be having a ready market even in periods of stress.

3. A limit on loan to deposit ratio.

4. A limit on loan to capital ratio.

5. A general limit on the relationship between anticipated funding needs and available sources for meeting those needs.

6. Primary sources for meeting funding needs should be quantified.

7. Flexible limits on the percentage reliance on a particular liability category, (e.g., certificates of deposits should not account for more than certain per cent of total liabilities).

8. Limits on the dependence on individual customers or market segments for funds in liquidity position calculations.

9. Flexible limits on the minimum/maximum average maturity of different categories of liabilities.

10. Minimum liquidity provision to be maintained to sustain operations.

An example of setting tolerance level for a bank:

1. To manage the mismatch levels so as to avert wide liquidity gaps – The residual maturity profile of assets and liabilities will be such that mismatch level for time bucket of 1-14 days and 15-88 days remains around 80% of cash outflows in each time bucket.

2. To manage liquidity and remain solvent by maintaining short-term cumulative gap up to one year (short-term liabilities – short-term assets) at 15% of total out flow of funds.

Banks should analyse the likely impact of different stress scenarios on their liquidity position and set their limits accordingly. Limits should be appropriate to the size complexity and financial condition of the bank. Management should define the specific procedures and approval necessary for exceptions to policies and limits.

Essay # 3. Measuring and Managing Liquidity Risk:

Measuring and managing funding requirement can be done through two approaches:

(A) Stock approach, and

(B) Flow approach.

(A) Stock Approach (To Measuring and Managing Liquidity):

Stock approach is based on the level of assets and liabilities as well as off-balance sheet exposures on a particular date.

The following ratios are calculated to assess the liquidity position of a bank:

(a) Ratio of Core Deposit to Total Assets – Core Deposit/Total Assets:

More the ratio, better it is because core deposits are treated to be the stable source of liquidity. Core deposit will constitute deposits from the public in the normal course of business.

(b) Net Loans to Totals Deposits Ratio – Net Loans/Total Deposits:

It reflects the ratio of loans to public deposits or core deposits. Total loans in this ratio represent net advances after deduction of provision for loan losses and interest suspense account. Loan is treated to be less liquid asset and therefore lower the ratio, better it is.

(c) Ratio of Time Deposits to Total Deposits – Time Deposits/Total Deposits:

Time deposits provide stable level of liquidity and negligible volatility. Therefore, higher the ratio better it is.

(d) Ratio of Volatile Liabilities to Total Assets – Volatile Liabilities/Total Assets:

Volatile liabilities like market borrowings are to be assessed and compared with the total assets. Higher portion of volatile assets will pause higher problems of liquidity. Therefore, lower the ratio better it is.

(e) Ratio of Short-Term Liabilities to Liquid Assets – Short-Term Liabilities/Liquid Assets:

Short-term liabilities are required to be redeemed at the earliest. Therefore, they will require ready liquid assets to meet the liability. It is expected to be lower in the interest of liquidity.

(f) Ratio of Liquid Assets to Total Assets – Liquid Assets/Total Assets:

Higher level of liquid assets in total assets will ensure better liquidity. Therefore, higher the ratio, better it is. Liquid assets may include bank balances, money at call and short notice, inter-bank placements due within one month, securities held for trading and available for sale having ready market.

(g) Ratio of Short-Term Liabilities to Total Assets — Short-term Liabilities/Total Assets:

Short-term liabilities may include balances in current account, volatile portion of savings accounts leaving behind core portion of saving which is constantly maintained. Maturing deposits within a short period of one month. A lower ratio is desirable.

(h) Ratio of Prime Asset to Total Asset – Prime Asset/Total Assets:

Prime assets may include cash balances with the bank and balances with banks including central bank which can be withdrawn at any time without any notice. More or higher the, ratio better it is.

(i) Ratio of Market Liabilities to Total Assets – Market Liabilities/Total Assets:

Market liabilities may include money market borrowings, inter-bank liabilities repayable within a short period. Lower the ratio, better it is.

(B) Flow Approach (to Measuring and Managing Liquidity):

The framework for assessing and managing bank liquidity through flow approach has three major dimensions:

(a) Measuring and managing net funding requirements

(b) Managing market access

(c) Contingency planning.

(a) Measuring and Managing Net Funding Requirements:

Flow approach is the basic approach being followed by Indian banks. It is called gap method of measuring and managing liquidity. It requires the preparation of structural liquidity gap report. In this method, net funding requirement is calculated on the basis of residual maturities of assets and liabilities. These residual maturities will represent the net cash flow, i.e., difference of outflow and inflow of cash in the future time buckets.

These calculations are based on the past behaviour pattern of assets and liabilities as well as off-balance sheet exposures. Cumulative gap is calculated at various time buckets. It shows that at a particular time after week/fortnight/month/quarter/half year/year cash outflow and inflow difference will be represented by gap. In case the gap is negative, the bank will have to manage the shortfall through various sources according to the liquidity policy and strategy of the bank.

The analysis of net funding requirements involves the construction of a maturity ladder and the calculation of a cumulative net excess or deficit of funds at selected maturity dates. A bank’s net funding requirements are determined by analysing its future cash flows, based on assumptions of the future behaviour or assets, liabilities and off-balance-sheet items, and then calculating the cumulative net excess over the time frame for the liquidity assessment.

These aspects will be elaborated under the following heads:

(i) The Maturity Ladder

(ii) Alternative Scenarios

(iii) Measuring Liquidity Over the Chosen Time-frame

(iv) Assumptions Used in Determining Cash Flows.

(i) The Maturity Ladder:

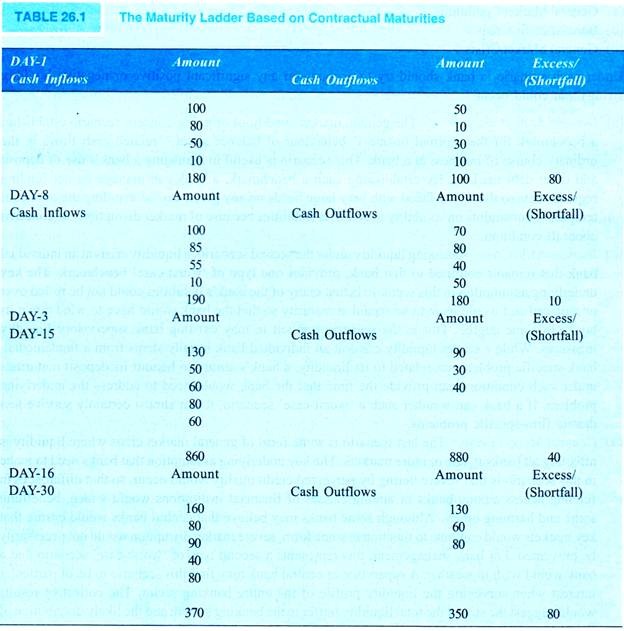

A maturity ladder should be used to compare a bank’s future cash inflows to its future cash outflows over a series of specified time periods. Cash inflows arise from maturing assets, saleable non-maturing assets and established credit lines that can be trapped. Cash outflows include liabilities falling due and contingent liabilities, especially committed lines of credit that can be drawn down. In Table 26.1, the maturity ladder is represented by placing sources and amounts of cash inflows on one side of the page and sources and amounts of outflows on the other.

In constructing the maturity ladder, a bank has to allocate each cash inflow or outflow to a given calendar date from a starting point, usually the next day. As a preliminary step to constructing the maturity ladder, cash inflows can be ranked by the date on which assets mature or a conservative estimate of when credit lines can be drawn down.

Similarly, cash outflows can be ranked by the date on which liabilities fall due, the earliest date a liability holder could exercise an early repayment option, or the earliest date contingencies can be called. Significant interest and other cash flows should also be included. The difference between cash inflows and cash outflows in each period, the excess or deficit of funds, becomes a starting-point for a measure of a bank’s future liquidity excess or shortfall at a series of points in time.

It is this net funding requirement that requires management. Typically, a bank may find substantial funding gaps in distant periods and will endeavor to fill these gaps by influencing the maturity of transactions so as to offset the gap. For example, if there is a significant funding requirement 30 days hence, a bank may choose to acquire an asset maturing on that day, or seek to renew or roll over the liability.

The closer a large gap gets, the more difficult it is to offset. Thus, banks will typically collect data on relatively distant period so as to maximise the opportunities to close the gap before it gets too close. Most bank would regard it important that any remaining borrowing requirement should be limited to an amount which experience suggests is comfortably within the bank’s capacity to fund in the market.

(ii) Alternative Scenarios:

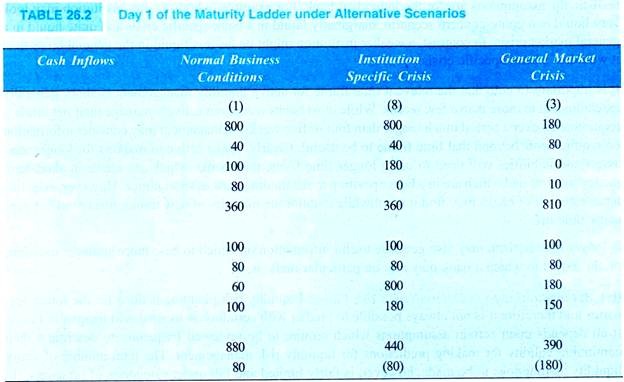

This involves evaluating whether a bank has sufficient liquidity depends in large measure on the behaviour of cash flows under the different conditions. Analysing liquidity thus entails laying out ‘what if’ scenarios.

There may be three scenarios for a bank in connection with management of liquidity which provide useful benchmarks:

a. General Market Conditions,

b. Bank-Specific Crisis, and

c. General Market Crisis.

Under each scenario, a bank should try to account for any significant positive or negative liquidity swings that could occur.

a. General Market Conditions:

The general market conditions or going-concern scenario establishes a benchmark for the ‘normal business’ behaviour of balance sheet – related cash flows in the ordinary course of business at a bank. This scenario is useful in managing a bank’s use of deposit and other debt markets.

By establishing such a benchmark, a bank can manage its net funding requirements so that is not faced with very large needs on any given day, so avoiding the impact of temporary constraints on its ability to roll over liabilities because of market disruptions or concerns about its condition.

b. Bank-Specific Crisis:

Assessing liquidity under the second scenario, a liquidity crisis at an individual bank that remains confined to that bank, provides one type of ‘worst-case’ benchmark. The key underlying assumption in this scenario is that many of the bank’s liabilities could not be rolled over or replaced and would have to be repaid at maturity so that the bank would have to wind down its books to some degree.

This is the scenario implicit in May existing bank supervisory liquidity measures. While a severe liquidity crisis at an individual bank usually stems from a fundamental, bank-specific problem not related to its liquidity, a bank’s ability to honour its deposit maturities under such conditions can provide the time that the bank would need to address the underlying problem. If a bank can weather such a ‘worst-case’ scenario, it can almost certainly survive less drastic firm-specific problems.

c. General Market Crisis:

The last scenario is some form of general market crisis where liquidity is affecting all banks in one or more markets. The key underlying assumption that banks need to make in this scenario is that severe tiering by perceived credit quality would occur, so that differences in funding access among banks or among classes of financial institutions would widen, benefiting some and harming others.

Although some banks may believe that central banks would ensure that key markets would continue to function in some form, severe market disruption would not necessarily be prevented. For bank management, this represents a second type of ‘worst-case’ scenario that a bank would wish to weather.

A supervisor or central bank may find this scenario to be of particular interest when surveying the liquidity profile of the entire banking sector. The collective results would suggest the size of the total liquidity buffer in the banking system and the likely distribution of liquidity problems among large institutions if the banking systems as a whole experience a shortage of liquidity.

The bank’s historical experience of the pattern of flows and a knowledge of market conventions could guide a bank’s decisions, but judgement often plays a large role, especially in crisis scenarios. Uncertainty is an inevitable element in choosing between possible behaviour pattern, and that dictates a conservation approach that would bias a bank toward assigning later dates to cash inflows and earlier dates to cash outflows.

Hence, the timing of cash inflows and outflows on the maturity ladder can differ between the normal business approach and the two crisis scenarios, as shown in Table 26.2. In constructing the going concern maturity ladder, conservative assumptions need to be made about the behaviour of cash flows that can replace the contractual cash flows. For example, many maturing loans would be rolled over in the normal course of business and some proportion of transactions and savings deposit would also be rolled over or could be easily replaced.

In a bank-specific crisis scenario it is assumed that a bank will be unable to roll over or replaced many or most of its liabilities, and that it may have to wind down its books to some degree. The assumptions under the third scenario, a general market crisis, may differ quite sharply from the assumptions made for a bank-specific crisis.

For example, a bank may believe, based upon its historical experience, that its ability to control the level and timing of future cash flows from a stock of saleable assets in a bank specific funding crisis would deteriorate little from normal conditions. However, in a general market crisis, this capacity may fall off sharply if few institutions are willing or able to make cash purchase of less liquidity assets.

On the other hand, a bank that has a high reputation in the market may actually benefit from a flight to quality as potential depositors seek out the safest home for their funds. Banks may also anticipate the central banks would ensure that key markets continue to function but not necessarily without significant disruption.

(iii) Measuring Liquidity Over the Chosen Time frame:

The evolution of a bank’s liquidity profile under one or more scenarios can be tabulated or portrayed graphically, by cumulating the balance of expected cash inflows and cash outflows at several time points. A stylised liquidity graph can be constructed, enabling the evolution of the cumulative net excess or deficit of funds to be compared under the three scenarios in order to provide further insights into a bank’s liquidity and to check how consistent and realistic the assumptions are for the individual bank.

For example, a high-quality institution may look very liquid in a going-concern scenario, marginally liquid in a bank-specific crisis and quite liquid in a general market crisis. In contrast, a weaker institution might be far less liquid in the general crisis than it would in a bank-specific crisis.

It is important to note that the relevant time frame for active liquidity management is short, generally extending out to more than a few weeks. While most banks would not actively manage their net funding requirements over a period much longer than four or five weeks, management may consider information on requirements beyond that time frame to be useful.

Clearly, banks active in markets for longer term assets and liabilities will need to use a longer time frame than banks which are active in short-term money markets and which are in a better position to fill funding gaps as short notice. However, even this latter category of banks may find it worthwhile to tailor the maturity of new transactions to offset gaps some time off.

A longer time horizon may also generate useful information on which to base more strategic decisions on the extent to which a bank may rely on particular markets.

(iv) Assumptions Used in Determining Cash Flows:

Liquidity risk planning is done for the future scenarios and therefore it is not always possible to predict with certainty as to what will happen in future. It all depends upon certain assumptions which require to be reviewed frequently to determine their continuing validity for making predictions for liquidity risk management.

The total number of major liquidity assumptions to be made, however, is fairly limited and fall under categories of:

a. Assets,

b. Liabilities,

c. Off-Balance-Sheet Activities, and

d. Others.

a. Assumptions Regarding Assets:

Assumptions about a bank’s future stock of assets include their potential marketability and use as collateral of existing assets which could increase cash inflows, and the extent to which maturing assets will be renewed, and new assets acquired, thus reducing contractual cash inflows.

Determining the level of a bank’s potential assets involves answering three questions:

i. What proportion of maturing assets will a bank be able and willing to roll over or renew?

ii. What is the expected level of new loan requests that will be accepted?

iii. What is the expected level of drawdowns of commitments to lend that a banks will need to fund?

In estimating its normal funding needs, some banks use historical patterns of roll-overs, drawdowns and new requests for loans; others conduct a statistical analysis taking account of seasonal and other effects believed to determine loan demand (e.g. for consumer loans). Alternatively, a bank may make judgemental business projections, or undertake a customer-by-customer assessment for its larger customer and apply historical relationship to the remainder.

Roll-overs, drawdowns and new loan requests all represent potential cash drains for a bank. Nevertheless, a bank has some leeway to control many of these items depending on the assumed scenario. In a crisis situation, for example, a bank might decide to risk damaging some business relationships by refusing to roll-over loans that it would make under normal conditions, or it might refuse to honour lending commitments that are not binding.

In determining the marketability of assets, the approach segregates the assets into three categories by their degree of relative liquidity:

i. The most liquid category includes components such as cash, securities, and interbank loans. Some of these assets may be immediate convertible into cash at prevailing market values under almost any scenario (either by outright sale, or for sale and repurchase, or as collateral for secured financing), while others, such as interbank loans or some securities, may lose liquidity in a general crisis

ii. A less liquid category comprises a bank’s saleable loan portfolio. The task here is to develop assumptions about a reasonable schedule for the disposal of a bank’s assets. Some assets, while marketable, may be viewed as unsaleable within the time frame of liquidity analysis

iii. The least liquid category includes essentially unmarketable assets such as loans not capable of being readily sold, bank premises and investments in subsidiaries, as well as, possibly, severely trouble credits

iv. Assets pledged to third parties are deducted from each category

The view underlying the classification process is that different banks could assign the same asset to different categories on the maturing ladder because of differences in their internal asset-liability management. For example, a loan categorised by one bank as a moderately liquid asset saleable only late in the liquidity analysis time frame may be considered a candidate for fairly quick and certain liquidation at a bank that operates in a market where loans are frequently transferred, that routinely include loan – sale clauses in all loan documentation and that has developed a network of customers with whom it has concluded loan-purchase agreement.

In categorising assets, a bank would also have to decide how an asset’s liquidity would be affected under different scenarios. Some assets that may be very liquid during times of normal business conditions may be less so during a time of crisis. Consequently, a bank may place an asset in different categories depending on the type of scenario it is forecasting.

b. Assumptions Regarding Liabilities:

To evaluate the cash flows arising from a bank’s liabilities, a bank would first examine the behaviour of its liabilities under the normal business conditions.

This would include establishing:

i. The normal level of roll-overs of deposits and other liabilities,

ii. The effective maturity of deposits with non-contractual maturities, such as demand deposits and many types of saving accounts, and

iii. The normal growth in new deposit accounts.

As in assessing roll-overs and new requests for loans, a bank could use several possible techniques to establish the effective maturities of its liabilities, such as using historical patterns of deposit behaviour. For sight deposits, whether of individuals or business, many banks conduct a statistical analysis that takes account of seasonal factors, interest rate sensitivities, and other macroeconomic factors. For some large wholesale depositors, a bank may undertake a customer-by-customer assessment of the probability of roll-over.

In examining the cash flows arising from a bank’s liabilities in the two crisis scenarios, a bank would examine the following basic questions:

i. Which sources of funding are likely to stay with a bank under any circumstances, and can these be increased?

ii. Which sources of funding can be expected to run off gradually if problems arise and at what rate? Is deposit pricing a means of controlling the rate of run off?

iii. Which maturing liabilities or liabilities with non-contractual maturities can be expected to run off immediately at the first sign of trouble? Are these liabilities with early withdrawal options that are likely to be exercised?

iv. Does the bank have back-up facilities that it can drawdown?

First two categories:

The first two categories represent cash-flows developments that tend to reduce the cash outflows project directly from contractual maturities. In addition to the liabilities identified above, a bank’s capital and term liabilities not maturing within the horizon of the liquidity analysis provide a liquidity buffer.

The liabilities that make up the first category may be thought to stay with a bank, even under a ‘worse- case’ projection. Some core deposits generally stay with a bank because retail and small business depositors may rely on the public sector safety net to shield them from loss, or because the cost of switching banks, especially for some business services such as transactions accounts, is prohibitive in the very short run.

Second category:

The second category liabilities that are likely to stay with a bank during periods of mild difficulties and to run off relatively slowly in a crisis include core deposits that are not already included in the first category. In addition to core deposits, in some countries. Some level of particular types of interbank and government funding may remain with a bank during such periods, although interbank and government’s deposits are often viewed as volatile. A bank’s own liability roll-over experience as well as the experiences of other troubled institutions should help in developing a timetable for these cash flows.

Third category:

The third category comprises the remainder of the maturing liabilities, including some without contractual maturities, such as wholesale deposits. Under each scenario, this approach adopts a conservative stance and assumes that these remaining liabilities are repaid at the earliest possible maturity, especially in crisis scenario, because such money may flow to government securities and other safe havens.

Factors such as diversification and relationship building are seen as especially important in evaluating the extent of liability run-off and a bank’s capacity to replace funds. Nevertheless, in a general market crisis, some high quality institution may find that they receive larger-than-usual wholesale deposit inflows, even as funding inflows dry up for other market participations.

Some banks, for example, smaller banks in regional markets, may also have credit lines that they can drawdown to offset cash outflows. While these sorts of facility are somewhat rare among larger banks, the possible use of such lines could be addressed with a bank’s liability assumptions. Where such facilities are subject to material adverse change clause, of course they may be of limited value, especially in a bank specific crisis.

c. Off-Balance Sheet Activities:

A bank should also examine the potential for substantial cash flows from its off-balance sheet activities (other than the loan commitments already considered), even if such cash flows are not always a part of bank’s current liquidity analysis.

Contingent liabilities, such as letters of credit and financial guarantees, represent potentially significant cash drains for a bank, but are usually not dependent on a bank’s condition. A bank may be able to ascertain a ‘normal’ level of cash outflows on an ongoing concern basis, and then estimate the scope for an increase in these flows during periods of stress. However, a general market crisis may trigger a substantial increase in the amount of draw-downs of letters of credit because of an increase in defaults and bankruptcies in the market.

Other potential sources of cash outflows include swaps, written over-the-counter (OTC) options, and other interest rate and forward foreign rate contracts. If a bank has a large swap book, for example, then it would want to consider the circumstances under which the bank could become a net payer, and whether or not the potential net pay out is significant.

For example, if a bank is a swap market-maker, the possibility exists that in a bank-specific or general market crisis, customers with in-the-money swaps (or a net in-the-money swap position) would seek to reduce their credit exposure to the bank by asking the bank to buy outstanding warrants, together with any hedges against these positions, since certain types of crisis may simulate an increase in early exercise (for American style options) or requests that the bank repurchase options. These exercise and repurchase requests could result in an unforeseen cash drain, if hedges either be quickly liquidated to generate cash or provide insufficient cash.

d. Other Assumptions:

The discussion has centered so far on assumptions concerning the behaviour of specific instrument under various scenarios. Looking solely at instruments, however, may ignore some factors that may have significant impact a bank’s cash flows.

Besides the liquidity needs arising from business activities, banks also require excess funds to support other operations. For example, many large banks provide clearing services to correspondent banks and financial institutions that generate significant and not always easily predictable cash inflows and outflows, the amounts of which depend on the clearing column, of the correspondent banks. Unforeseen fluctuations in these volumes can deplete a bank of needed funds.

Net overhead expenses, such as rent and salary, although generally not significant enough to be considered in bank’s liquidity analyses, can in some cases also be sources of cash outflows.

(b) Managing Market Access:

Some liquidity management techniques are viewed not only for their influence on the assumptions used in constructing maturity ladders, but also for their direct contribution to enhancing a bank’s liquidity. Thus, it is important for a bank to review periodically its efforts to maintain the diversification of liabilities, to establish relationships with liability holders and to develop asset-sales markets.

As a check for adequate diversification of liabilities, a bank needs to examine the level of reliance on individual funding sources, by instrument type, nature of the provider of funds, and geographic market. In addition, a bank should strive to understand and evaluate the use of inter-company financing for its individual business officers.

Building strong relationships with some providers of funding can provide line of defence in a liquidity problem and form an integral part of a bank’s liquidity management. The frequency of contract and the frequency of use of funding source are two possible indicators of the strength of a funding relationship.

Developing markets for asset sales or exploring arrangements under which a bank can borrow against assets is the third element of managing market access. The inclusion of loan-sale clauses in loan documentation and the frequency of use of some asset-sales markets are two possible indicators of a bank’s ability to execute asset sales under adverse scenarios.

(c) Contingency Planning:

A bank’s ability to withstand a net funding requirement in a bank-specific or general market liquidity crisis can also depend on the caliber of its formal contingency plans.

Effective contingency plans should address two major questions:

i. Does management have a strategy for handling a crisis?

ii. Does management have procedures in place for accessing cash in emergency?

The degree, to which a bank has addressed these questions realistically, provides management with additional insight as to how a bank may fare in a crisis.

Strategy for Handling a Crisis:

A game plan for dealing with a crisis should consist several components. Most important are those that involve managerial coordination. A contingency plan needs to spell out procedures to ensure that information flows remain timely and uninterrupted, and that the information flows provide senior management with the precise information it needs in order to make quick decisions. A clear division of responsibility must be set out so that all personnels understand what is expected of them during a crisis. Confusion in this area can waste resources on certain issues and omit coverage on others.

Another major element in the plan should be a strategy for taking certain actions to alter asset and liability behaviours. While assumptions can be made as to how an asset or liability will behave under certain conditions (as discussed above), a bank may have the ability to change these characteristics. For example, a bank may conclude that it will suffer a liquidity deficit in a crisis, based on its assumptions regarding the amount of future cash inflows from saleable assets and outflows from deposit run-offs.

During such a crisis, however, a bank may be able to market assets more aggressively, or sell assets that it would not have sold under normal conditions and thus augment its cash inflows from asset sales. Alternatively, it may try to reduce cash outflows by raising its deposit rates to retain deposits that might otherwise have moved elsewhere.

Other components of the game plan involve maintaining customer relationships with borrowers, trading and off-balance-sheet counter parties, and liability holders. As the intensity of a crisis increases, banks must often trade off relationships with some customer for liquidity in order to survive. By classifying borrowers and trading customers according to their importance to the bank, a bank can determine which relationship it may need to forgo at different points in a crisis.

At the same time, relationship with lenders becomes more important in a crisis. If a bank’s strategy requires liability managers to maintain strong ongoing links with lenders and large liability holders during periods of relative calm, the bank will be better positioned to secure sources of funds during emergencies.

An additional pragmatic element that may be important is how a bank deals with the press and broadcast media. Astute public relations management can help a bank avoid the spread of public rumours that can result in significant run-offs by retail depositors and institutional investors.

Back up Liquidity for Emergency Situations:

Contingency plans should also include procedures for making up cash flow shortfalls in emergency situations. Banks have available to them several sources of such funds, including previously unused credit facilities and the domestic central bank. Depending on the severity of a crisis, a bank may choose – or be forced – to use one or more of these sources. The plan should spell out as clearly as possible the amount of funds a bank has available from these sources, and under what scenarios a bank could use them.

Reserve Bank of India Guidelines for Maturity Buckets:

Reserve Bank of India has given a framework for bucket-wise classification of assets and liabilities to be followed by Indian banks. These are the guiding factors for the banks.

All the assets and liabilities are classified into ten time buckets as given below:

i. Tomorrow

ii. 2-7 days

iii. 8-14 days

iv. 15-28 days

v. 29 days and up to 3 months

vi. Over 3 months and up to 6 months

vii. Over 6 months and up to 1 year

viii. Over 1 year and up to 3 year

ix. Over 3 years and up to 5 years

x. Over 5 years.