Here is a compilation of essays on ‘Internet and Business’ for class 11 and 12. Find paragraphs, long and short essays on ‘Internet and Business’ especially written for college and management students.

Essay on Internet and Business

Essay Contents:

- Essay on the Introduction to Internet and Business

- Essay on the Distorted Market Signals

- Essay on Return to Fundamentals

- Essay on the Internet and Industry Structure

- Essay on Dot-Coms and Established Companies

- Essay on the Internet and Competitive Advantage

- Essay on the Absence of Strategy

- Essay on the Internet as Complement

- Essay on the End of New Economy

- Essay on the Words for the Unwise on the Internet

- Essay on the Internet and Value Chain

- Essay on the Prominent Applications of Internet in the Value Chain

- Essay on the Future of Internet Competition among Industries

Essay # 1. Introduction to Internet and Business:

Many of the Pioneers of Internet business, both dot-coms are established companies, have completed in way that violated nearly every precept of good strategy, Rather than focus on profits, they have chased customers indiscriminately through discounting, channel incentives, and advertising. Rather than concentrate on delivering value that ears on attracting price from customers, they have rushed to offer every conceivable product or service.

It did not have to be this way- and it does not have to be in the future. When it reinforcing a distinctive strategy, Michael Platform, than previous generation of IT. Gaining competitive advantage does not require a radically new approach to business, it requires building on the proven principles of effective strategy.

Porter argues that, contrary to recent thought, the Internet is not disruptive to most existing industries and established companies. It rarely nullifies important sources of competitive advantage in an industry. If often makes them even more valuable. And as all companies embrace Internet technology, the Internet itself will be neutralized as a source of advantage. Robust competitive advantages will arise instead from traditional strengths such as unique products, proprietary content, and distinctive physic activities. Internet technology may be able to fortify those advantages, but it is unlikely to supplant them.

Porter debunks such Internet myths as first-mover advantage, the power of virtual companies, and the multiplying rewards on network effects. He disentangles the distorted signals from the marketplace, explains why the Internet complements rather than cannibalized existing way of doing business, and outlines strategic imperatives for dot-coms and traditional companies.

The Internet is an extremely important new technology, and it is no surprise that it has received so much attention from entrepreneurs, executives, investors, and business observers. Caught up in the general fervor may have assumed that the Internet charges everything, rendering ail the old rules about companies and competition obsolete. That may be a natural reaction, but it is a dangerous one. It has led many companies, dot-coms and incumbents alike, to make bad decisions – decision that have eroded the attractiveness of their industries and undermined their own competitive advantage.

Some companies, for example, have used Internet technology’ to shift the basis of competition away from quality, features, and service and toward price, making it harder for anyone in their industries to turn a profit. Other has forfeited important proprietary advantage by rushing into misguided partnership and outsourcing relationships. Until recently, the negative effects of these actions have been obscured by distorted signals from the marketplace. Now, however, the consequences are becoming evident.

The time has come to take a clearer view of the Internet. We need to move any from the rhetoric about “Internet industries,” “e-business strategies” and a “new economic” and see the Internet for what it is an enabling technology- a powerful set of tools that can be used, wisely or unwisely, in almost any industry and as part of almost any strategy. We need to ask fundamental questions: Who will capture the economic benefits that the Internet creates? Will all the value ends up going to customer, or will companies be able to reap a share of it? What will be the Internet’s impact on industry structure? Will it expand or shrink the pool of profits? And what will be its impact on strategy? Will the Internet bolster or erode the ability of companies to gain sustainable advantages over their competitors?

In addressing these questions, much of what we find is unsettling. I believe that the experiences companies have had with the Internet thus for much be largely discounted and the many of the lessons learned must be forgotten. When seem with fresh eyes, it becomes clear that the Internet is not necessary a blessing. It tends to alter industry structures in ways that dampen overall profitability, and it has a leveling effect on business practices, reducing the ability of any company to establish an operational advantage that can be sustained.

The key question is not whether to deploy Internet technology- companies have any choice if they want to stay competitive- but how to deploy it. Here, there is reason for optimism. Internet technology provides better opportunities for companies to establish distinctive strategic positionings than did previous generations of information technology. Gaining such a competitive advantage does not require a radically new approach to business. It requires building on the proven principles of effective strategy. The Internet per se will rarely be a competitive advantage.

Many of the companies that succeed will be ones that use of Internet as a complement to traditions ways of competing, not those that set their Internet initiatives apart from their established operations. That is particularly good news for established companies, which are often in the best position to meld Internet and traditional approaches in way that buttress existing advantages.

But dot-coms can also be winners – if any understand the trade -offs between Internet and traditional approaches and can fashion truly distinctive strategies. Far from making strategy less important, as some have argued, the Internet actually makes strategy more essential than ever.

Essay # 2. Distorted Market Signals:

Companies that have deployed Internet technology have been confused by distorted market signals, often of their own creation. It is understandable, when confronted with a new business phenomenon, to look to market place outcomes for guidance. But in the early stages of the rollout of any important new technology, market signals can be unreliable. New technologies trigger rampant experimentation, “both companies and customers, and the experimentation is often economically unsustainable. As a result, market behavior is distorted and must be interpreted with caution.

That is certainly the case with the Internet. Consider the revenue side of the profit equation in industries in which Internet technology is widely used. Sales figures have been unreliable for three reasons. First, many companies have subsidized the purchase of their products and services in hopes of staking out a position on the Internet and attracting a base of customers. (Government have also subsidized on -line shopping by exempting it from sales taxes.) Buyers have been able to purchase goods at heavy discounts, or even obtain them for free, rather than pay prices that reflect true costs. When prices are artificially low, unit demand becomes artificially high.

Second, many buyers have been drawn to the Internet out of curiosity; they have been willing to conduct transactions on-line even when the benefits have been uncertain or limited. If Amazon(dot)com offers an equal or lower price than a conventional bookstore and free or subsidized shipping, why not try it as an experiment? Sooner or later, through, some customers can be expected to return to more traditional modes of commerce, especially if subsidies end, making any assessment of customer loyalty based on conditions so far suspect.

Finally, some “revenues” from on-line commerce have been received in the form of stock rather than cash. Much of the estimated $450 million in revenues that Amazon has recognized from its corporate partners, for example, has come as stock. The sustainability of such revenue is questionable, and its true value hinges on fluctuations in stock prices.

If revenue is an elusive concept on the Internet, cost is equally fuzzy. Many companies doing business on-line have enjoyed subsidized inputs. Their suppliers, eager to affiliated themselves with and learn from dot-com leaders, have provided products, services, and heavily discounted prices. Many content providers, for example, rushed to provide their information to Yahoo! For next to nothing in hopes of establishing a beachhead on one of Internet’s most visited sites.

Some providers have even paid popular portals to distribute their content. Further masking true costs, many suppliers not to mention employees- have agreed to accept equity, warrants, or stock options from Internet-related companies and ventures in payment for their services or products. Payment in equity does not appear on the income statement, but it is a real cost to shareholders.

Such supplier practices have artificially depressed the costs of doing business on the Internet, making it appear more attractive than it really is. Finally, costs have been distorted by the systematic understatement of the need for capital. Company after company touted the low assets intensity of doing business on-line, only to find that inventory, warehouses, and other investments were necessary to provided value to customers.

Signals from the stock market have been even more unreliable. Responding to investor enthusiasm over the Internet’s explosive growth, stock valuations become decoupled from business fundamentals. They no longer provided an accurate guide as to whether real economic value was being created. Any company that has made competitive decisions based on influencing near-term share price or responding to investor sentiments has put itself at risk.

Distorted revenues, costs and share prices have been matched by the unreliability of the financial metrics that companies have adopted. The executives of companies conducting business over the Internet have, conveniently, downplayed traditional measures to profitability and economic value. Instead, they have emphasize expansive definitions of revenue, numbers of customers, or, even more suspect, measures that might someday correlate with revenue, such as numbers of unique users (“reach”), numbers of site visitors, or click-through rates.

Creative accounting approaches have also multiplied. Indeed, the Internet has given rise to an array of new performance metrics that have only a loose relationship to economic value, such as pro forma measures of income that remove “nonrecurring” costs like acquisitions. The dubious connection between reported metrics and actual profitability has served only to amplify the confusing signals about what has been working in the market place. The fact that those metrics have been taken seriously by the stock market has muddied the waters even further. For all these reasons, the true financial performance of many Internet-related businesses is even worse than been stated.

One might argue that the simple proliferation of dot-coms is a sign of the economic value of the Internet. Such a conclusion is premature at best. Dot-coms multiplied so rapidly for one major reason: they were able to raise capital without having to demonstrate viability. Rather than signaling a healthy business environment, the sheer number of dot-coms in many industries often revealed nothing more than the existence of low barriers to entry, always a danger sign.

Essay # 3. A Return to Fundamentals:

It is hard to come to any firm understanding of the impact of the Internet on business by looking at the results to date. But two broad conclusions can be drawn. First, many businesses active on the Internet are artificial businesses competing by artificial means and propped up by capital that until recently had been readily available. Second, in periods of transition such as the one we have been going through, it often appears as if there are new rules of competition. But as market forces pay out, as they are now, the old rules regain their currency. The creation of true economic value once again becomes the final arbiter of business success.

Economic value for a company is nothing more than the gap between price and cost, and it is reliable measured only by sustained profitability. To generate revenues, reduce expenses, or simply do something useful by deploying Internet technology is not sufficient evidence that value has been created. Not is a company’s current stock price necessarily an indicator of economics value. Shareholder value is a reliable measure of economic value only over the long run.

In thinking about economic value, it is useful to draw a distinction between the uses of the Internet (such as operating digital marketplaces, selling toys, or trading securities) and Internet technologies (such as site customization tools or real-time communication services), which can be deployed across many uses. Many have pointed to the success of technology providers as evidence of the Internet’s economics value. But this thinking is fault. It is the use of the Internet that ultimately creates economic value.

Technology providers can prosper for a time irrespective of whether the uses of the Internet are profitable. In periods of heavy experimentation, even selling of flawed technologies can thrive. But unless the use generate sustainable revenues or savings in excess of their cost of deployment, the opportunity for technology provides will shrivel as companies realize that further investment is economically unsound.

So how can the Internet are used to create economic value? To find the answer, we need to look beyond the immediate market signals to the two fundamental factors that determine profitability:

a) Industry structure, which determines the profitability of the average competitor; and

b) Sustainable competitive advantage, which allows a company to outperform the average competitor.

These two underlying drivers of profitability are universal; they transcend and technology or type of business. As the same time, they vary widely by industry and company. The broad, supra- industry classifications so common in Internet parlance, such as business-to-customer (or “B2C”) and business-to-business (or “B2B”) prove meaningless with respect to profitability. Potential profitability can be understood only by looking at individual industries and individual companies.

Essay # 4. The Internet and Industry Structure:

The Internet has created some new industries, such as on-line actions and digital marketplaces. However, its greatest impact has been to enable the reconfiguration of existing industries that had been constrained by high costs for communicating, gathering information, or accomplishing transactions. Distance learning, for example, has existed for decades, with about one million students enrolling in correspondence sources every year.

The Internet has the potential to greatly expand distance learning, but it did not create the industry. Similarly, the Internet provides an efficient means to order products, but catalog retailers with toll-free numbers and automated fulfillment centers have been around for decades.

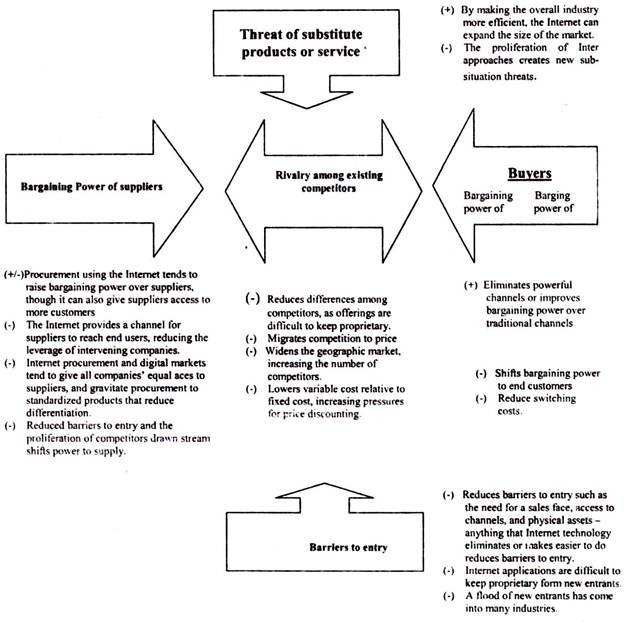

Whether an industry is new or old, its structural attractiveness is determined by five underlying forces of competition: the intensity of rivalry among existing competitors, the barriers to entry for new competitors, the threat of substitute products of services, the bargaining power of suppliers, and the bargaining power of buyers.

In combination, these forces determine how the economic value created by any product, service, technology, or way of competing is divided between, on the other, customers, suppliers, distributors, substitutes, and potential new entrants. Although some have argued that today’s rapid pace of technological change makes industry analysis less valuable, the opposite is true.

Analyzing the force illuminates an industry’s fundamental attractiveness, exposes the underlying drivers of average industry profitability, and provides insight into how profitability will evolve in the future. The five competitive forces still determines, profitability even if suppliers, channels, substitutes, or competitors change.

Because the strength of each of the five forces varies considerable from industry to industry, it would be a mistake to draw general conclusions about the impact of the Internet on long-term industry profitability; each industry is affected in different ways. Nevertheless, an examination of a wide range of industries in which the Internet is playing a role reveals some clear trends, as summarized in the exhibit “How the Internet Influences Industry Structure.”

Some of the trends are positive. For example, the Internet tends to dampen the bargaining power of channels by providing companies with new, more direct avenues to customers. The Internet can also boost an industry’s efficiency in various ways, expanding the overall size of the market by improving its position relative to traditional substitutes.

But most of the trends are negative. Internet technology provides buyers with easier access to information about products and suppliers, thus bolstering buyer bargaining power. The Internet mitigates the need for such things as an established sales force or access to exiting channels, reducing barriers to entry. By enabling new approaches to meeting needs and performing functions, it creates new substitutes.

Because it is an open system, companies have more difficulty maintaining proprietary offerings, thus intensifying the rivalry among competitors. The use of the Internet also tends to expand the geographical market, brining many more companies into competition with one another. And Internet technological tend to reduce variable costs and tilt cost structures towards fixed cost, creating significantly greater pressure for companies to engage in destructive price competition.

While deploying the Internet can expand the market, then, doing so often comes at the expense of average profitability. The great paradox of the Internet is that it’s very benefits-making information widely available; reducing the difficult of purchasing, marketing, and distribution; allowing buyers and sellers to find and transact business with one another more easily- also make it more difficult for companies to capture those benefits as profits.

We can see the dynamic at work in automobile retailing. The Internet allows customers to gather extensive information about products easily, from detailed specification and repair records to wholesale prices for new cars and average values for used cars Customers can also choose among many more options from which to buy, not just local dealers but also various types of Internet referral network (such as Auto web and Auto Vantage) and on-line direct dealers (such as Auto-bytel(dot)com, AutoNation, and CarsDiiect(dot)com).

Because the Internet reduces the importance of location, at least for the initial sale, it widens the geographic market from local to regional or national. Virtually every dealer or dealer group becomes a potential competitor in the market. It is more difficult, moreover, for on-line dealers to differentiate themselves, as they lack potential points of distinction such as showrooms, personal selling, and service departments. With more competitors selling largely undifferentiated products, the basis for competition shifts ever more toward price. Clearly, the net effect on the industry’s structure is negative.

Influence of Internet on Industry Structure:

That does not mean that every industry in which Internet technology is being applied will be unattractive. For a contrasting example, look at Inter auctions. Here, customers and suppliers are fragmented and thus have little power. Substitutes, such as classified ads and flea markets, have less reach and are less convenient to use. And through the barriers to entry are relatively modest, companies can build economics of scale, both in infrastructure and, even more important, in the aggregation of many buyers and sellers, they deter new competitors or place them at a disadvantage.

Finally, rivalry in this industry has been defined, largely by eBay, the dominant competitor, in terms of providing an easy-to use marketplace in which revenue comes from listing sale fees, while customers pay the cost of shipping. When Amazon and other rivals entered the business offering free auction, eBay maintained its prices and pursued other ways to attract and retain customers As a result, the destructive price competition characteristic of other on-line businesses has been avoided.

EBay’s role in the auction business provides an important lesson:

Industry structure is not fixed but rather is shaped to a considerable degree by the choices made by competitors; EBay has acted in ways that strengthen the profitability of its industry. In stark contrast, Buy(dot)com, a prominent Internet retailer, acted in ways that under mined its industry, not to mention its own potential for competitive advantage.

Buy(dot)com achieved $100 million in sales faster than any company in history, but it did so by defining competition solely on price. It sold products not only below full cost but at or below cost of good sole, with the vain hope that tit would make money in other ways. The company had no plan for being the low-cost provider; instead, it invested heavily in brand advertising and eschewed potential sources of differentiation by outsourcing all fulfillments and offering the bare minimum of customer service.

It also gave up the opportunity to set itself apart from competitors by choosing not to focus on selling particular goods: it moved quickly beyond electronics, its initial category, into numerous other product categories in which it had no unique offering. Although the company has been trying desperately to reposition itself, its early moves have proven extremely difficult to reverse.

Essay # 5. Dot-Coms and Established Companies:

At this critical juncture in the evolution of Internet technology, dot-coms and establishment companies face different strategic imperatives. Dot-coms must develop real strategies that create economic value. They must recognize that current ways of competing area destructive and futile and benefit neither themselves nor, in the end customers. Established companies, in turn, must stop deploying the Internet on a stand-alone basis and instead use if to enhance the distinctiveness of their strategies.

The most successful dot-coms will focus on creating benefits that customers will pay for, rather than pursuing advertising and click-through revenues from third parties. To be competitive, they will often need to widen their value chains to encompass other activities besides those conducted over the Internet and to develop other assets, including physical ones. Many are already doing so.

Some online retailers, for example, distributed paper catalogs for the 2000 holidays season as on added convenience to their shoppers. Others are introducing proprietary products under their own brand name, which not only boosts margins but also provides real differentiation. It is such new activities in the value chain, not minor differences in Web sites that hold the key to whether dot-coms gain competitive advantages.

AOL, the Inter pioneer, recognized these principles. It charged for its services even in the face of free competitors. And not resting on initial advantages gained from its Web site and Internet technologies (such as instant messaging), it moved early to develop or acquire proprietary content.

Yet dot-coms must not fall into the trap of imitating established companies. Simply adding conventional activities is a me-too strategy that will not provide a competitive advantage. Instead, dotcoms need to create strategies that involve new, hybrid value chains, bringing together virtual and physical activities in unique configurations. For example, E* trade is planning to install stand-alone kiosks, which will not require full time staffs, on the sites of some corporate customers. Virtual Bank, allows customers to deposit checks at Mail Box Etc. locations. While none of these approaches is certain to be successful, the strategic thinking behind them is sound.

Another strategy for dot-coms is to seek out tradeoffs, concentrating exclusively on segments where on Internet-only model offers real advantages, Instead of attempting to force the Internet model on the entire market, dot-coms can pursue customers that do not have a strong need for functions delivered outside the Internet -even if such customer represent only a modest portion of the overall industry. In such segment, the challenge will be to find a value proposition for the company that will distinguish it from other Internet rivals and address low entry barriers.

Successful dot-coms will have the following characteristics in common:

1. Strong capabilities in Internet technology.

2. A distinctive strategy vis-a-vis established companies and other dot-coms, resting on a clear focus and meaningful advantages.

3. Emphasis on creating customer value and charging for it directly, rather than relying on ancillary forms of revenue.

4. Distinctive ways of performing physical functions and assembling non-Internet assets that complement their strategic positions.

5. Deep industry knowledge to allow proprietary skills, information, and relationships to be established.

Established companies, for the most part need not be afraid of the Internet- the predictions of their demise at the hands and dot-coms were greatly exaggerated. Established companies possess traditional competitive advantages that will often continue to prevail; they also have inherent strengths in deploying Internet technology.

The greatest threat to an established company lies in either failing to deploy the Internet or failing to deploy if strategically. Every company needs an aggressive program to deploy the Internet throughout its value chain, using the technology to reinforce traditional competitive advantages and complement existing ways of competing.

The key is not to imitate rivals but to tailor Internet applications to a company’s overall strategy in ways that extend its competitive advantages and make them more sustainable. Schwab’s expansion of its brick-and-mortar branches by one-third since it started on-line trading, for example, is extending its advantages over Internet only competitors. The Internet, when used properly, can support greater strategic focus and a more tightly integrated activity system.

Edward Jones, a leading brokerage firm, is a good example of tailoring the Internet to strategy. Its strategy is to provide conservative, personalized advice to investors who value asset preservation and seek trusted, individualized guidance in investing. Target customers include retirees and small- business owners.

Edward Jones does not offer commodities, futures, options, or other risky forms of investment. Instead, the company stresses a buy-bonds, a blue-chip equities. Edward Jones operates a network of about 7,000 small offices, which are located conveniently to customers and are designed to encourage personal relationships with brokers.

Edward Jones has embraced the Internet for internal management functions, recruiting (25% of all job inquiries come via the Internet), and for providing account statement and other information to customers. However, it has no plan to offer on-line trading, as its competitors do. Self-directed, online trading does not fit Jones’s strategy not the value it aims to deliver to its customers. Jones, then has tailored the use of the Internet to its strategy rather than imitated rivals, The Company is thriving, outperforming rivals whose me-too Internet deployment have reduced their distinctiveness.

The established companies that will be most successful will be those that use Internet technology to make traditional activities better and those that find and implement new combinations of virtual and physical activities that were not previously possible.

Essay # 6. The Internet and Competitive Advantage:

If average profitability is under pressure in many industries influenced by the Internet, it becomes all the more important for individual companies to set themselves apart from the pack-to be more profitable than the average performer. The only way to do so is by achieving a sustainable competitive advantage- by operating at a lower cost, by commanding a premium price, or by doing both. Cost and price advantages can be achieved in two ways. One is operational effectiveness-doing the same things your competitors do but doing them better.

Operational effectiveness advantages can take myriad forms, including better technologies, superior inputs, better-trained people, or a more effective management structure. The other way to achieve advantage is strategic positioning-doing things differently from competitors, in a way that delivers a unique type of value to customers.

This can means offering a different set of features, a different array of services, or different logistical arrangements. The Internet affects operational effectiveness and strategic positioning in very different ways. It makes it harder for companies to sustain operational advantages, but it opens new opportunities for achieving or strengthening a distinctive strategic positioning.

Operational Effectiveness:

The Internet is arguable the most powerful tool available today for enhancing operational effectiveness. By easing and speeding the exchange of real-time information, it enables improvements throughout the entire value chain, across almost every company and industry. And because it is an open platform with common standards, companies can often tap into its benefits with much less investment than was required to capitalize on past generations of information technology.

But simply improving operational effectiveness does not provide a competitive advantage. Companies only gain advantages if they are able to achieve and sustain higher levels of operational effectiveness than competitors. That is an exceedingly difficult proposition even in the best of circumstances. Once a company establishes a new best practice, its rivals tend to copy it quickly. Best practice competition eventually leads to competitive convergence, with many companies doing the same things in the same way. Customers end up making decision based on price, undermining industry profitability.

The nature of Internet applications makes it more difficult to sustain operational advantages than ever. In previous generations of information technology, application development was often complex, arduous, time consuming, and hugely expensive. These traits made it harder to gain an IT advantage, but they also made it difficult for competitors to imitate information systems.

The openness of the Internet, combined with advances in software architecture, development tools, and modularity, makes it much easier for companies to design and implement applications. The drugstore chain CVS, for example, was able to roll out a complex Internet-based procurement application in just 60 days. As the fixed costs of developing systems decline, the barriers to imitation fall as well.

Today, nearly every company is developing similar types of Internet applications, often drawing on generic packages offered by third-party developers. The resulting improvements in operational effectiveness will be broadly shared, as companies converge on the same applications with the same benefits. Very rarely will individual companies be able to gain durable advantage from the deployment of “best-of breed” applications.

Strategic Positioning:

As it becomes harder to sustain operational advantages, strategic positioning becomes all the more important. If a company cannot be more operationally effective than its rivals, the only way to generate higher levels of economic value is to gain a cost advantage or price premium by competing in a distinctive way. Ironically, companies today define competition involving the Internet almost entirely in terms of operational effectiveness.

Believing that no sustainable advantages exist, they seek speed and agility, hoping to stay one step ahead of the competition. Of course, such as approach to competition becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy. Without a distinctive strategic direction, speeds a flexibility lead nowhere. Either no unique competitive advantages are created, or improvements are generic and cannot be sustained.

Having a strategy is a matter of discipline. It requires a strong focus on profitability rather than just growth, an ability to define a unique value proposition, and a willingness to make tough tradeoffs in choosing what not to do. A company must stay the course, even during times of upheaval, while constantly improving and extending its distinctive positioning. Strategy goes far beyond the pursuit of best practices.

It involves the configuration of a tailored value chain- the series of activities required to produce and deliver a product or service – that enables a company to offer unique value. To be defensible, moreover, the value chain must be highly integrated. When a company’s activities fit together as a self-reinforcing system, any competitor wishing to imitate a strategy must replicate the whole system rather than copy just one or two discrete product features or ways of performing particular activities.

Essay # 7. The Absence of Strategy:

Many of the pioneers of Internet business, both dot-com and established companies, have competed in ways that violate nearly every precept of good strategy. Rather than focus on profits, they have sought to maximize revenue and market share at all costs, pursuing customers indiscriminately through discounting, giveaways, promotions, channel incentives, and heavy advertising. Rather than concentrate on delivering real value that earns an attractive price from customers, they have pursued indirect revenue from sources such as advertising and click-through fees from Internet commerce partners. Rather than make trade-offs, they have rushed to offer every conceivable product, service, or type of information.

Rather than tailor the value chain in a unique way, they have aped the activities of rivals, Rather than build and maintain control over proprietary assets and marketing channels, they have entered into a rash of partnership and outsourcing relationships, further eroding their own distinctiveness. While it is true that some companies have avoided these mistakes, they are exceptions to the rule.

By ignoring strategy, may companies have under mined the structure of their industries, hastened competitive convergence, and reduced the likelihood that they or anyone else will gain a competitive advantage. A destructive, zero-sum form of competition has been set in motion that confuses the acquisition of customers with the building of profitability. Worse yet, price has been defined as the primary if not the sole competitive variable.

Instead of emphasizing the Internet’s ability to support convenience, service, specialization, customization, and other forms of value that justify attractive prices, companies have turned competition into a race to the bottom. Once competition is defined this way, it is very difficult to run back. (See “Words for the Unwise: The Internet’s Destructive Lexicon” at the end of this article.).

Even well established, well -run companies have been thrown off track by the Internet. Forgetting what they standard for or what makes them unique, they have rushed to implement hot Internet applications and copy the offerings of dot-coms. Industry leaders have compromised their existing competitive advantage by entering market segments to which they bring little that is distinctive.

Merrill Lynch’s move to imitate the low-cost on-line offerings of its trading rivals, from example, risks undermining its most precious advantage- its skilled brokers. And many established companies, reacting to misguided investor enthusiasm, have hastily cobbled together Internet units in a mostly futile effort to boost their value in the stock market.

It did not have to this way-and it does not have to be in the future. When it comes to reinforcing a distinctive strategy, tailoring activities, and enhancing fit, the Internet actually provides a better technological platform than previous generations of IT. Indeed, IT worked against strategy in the past.

Packaged software applications were hard to customize, and companies were often forced to change the way they conducted activities in order to conform to the “best practices” embedded in the software. It was also extremely difficult to connect discrete applications to one another. Enterprise resource planning (ERP) systems linked activities, but again companies were forced to adapt their ways of force for standardizing activities and speeding competitive convergence.

Internet architecture, together with other improvements in software architecture and development tools, has turned IT into a far more powerful tool for strategy. It is much easier to customize packaged Internet applications to a company’s unique strategic positioning. By providing a common. It delivery platform across the value chain, Internet architecture and standards also make it possible to build truly integrated and customized systems that reinforce the fit among activities. (See “The Internet and the Value chain” at the end of this article.”).

To gain these advantages, however, companies need to stop their rush to adopt generic; “out of the box” packaged applications and instead tailors their deployment of Internet technology to their particular strategies. Although it remains more difficult to customize packaged applications, the very difficult of the task contributes to the sustainability of the resulting competitive advantage.

Essay # 8. The Internet as Complement:

To capitalize on the Internet’s strategic potential, executives and entrepreneurs alike will need to change their point of view. It has been widely assumed that the Internet is cannibalistic, that it will replace all conventional ways of doing business and overturn all traditional advantages. That is a vast exaggeration. There is no doubt that real trade-offs can exist between Internet and traditional activities in the record industry, for example, on-line music distribution may reduce the need for CD- manufacturing assets.

Overall, however, the Internet will replace certain elements of industry value chains, the complete cannibalization of the value chain will be exceedingly rare. Even in the music business, may traditional activities- such as finding and promoting talented new artists, producing and recording music, and securing airplay – will continue to be highly important.

The risk of channel conflict also appears to have been overstated. As on line sales have become more common, traditional channels that were initially skeptical of the Internet have embraced it. Far from always cannibalizing those channels, Internet technology can expand opportunities for many them. The threat of disinter-mediation of channels appears considerably lower than initially predicted.

Frequently, in fact Internet applications address activities that, while necessary, are not decisive in competition, such as informing customers, processing transactions, and procuring inputs. Critical corporate assets – skilled personnel, proprietary product technology, and efficient logistical systems- remain intact, and they are often strong enough to preserve existing competitive advantages.

In many cases, the Internet complements, rather than cannibalizes, companies’ traditional activities and ways of competing. Consider Walgreens, the most successful pharmacy chain in the United States. Walgreens introduced a Web site that provides customers with extensive information and allows them to order prescriptions on-line. Far from cannibalizing the company’s stores, the web site has underscored their value. Fully 90% of customers who place orders over the web prefer to pick up their prescriptions at a nearby store rather than have them shipped to their homes. Walgreens has found that its extensive network of stores remains a potent advantage, even as some order shifts to the Internet.

Another good example is W.W. Grainger, a distributor of maintenance products and spare parts of companies. A middleman with stocking locations all over the United States, grainer would seem to be a textbook case of an old-economy company set to be made obsolete by the Internet. But Grainger rejected the assumption that the Internet would undermine its strategy. Instead, it tightly coordinated its aggressive on-line efforts with its traditional business.

The results so far are revealing. Customers who purchase on-line also continue to purchase through other means Grainger estimates a 9% increment growth in sales for customers who use the on-line channel above the normalized sales of customers who use only traditional means. Grainger, like Walgreens, has also found that Web ordering increases the value of its physical locations. Like the buyers of prescription drugs, the buyers of industrial supplies often need their orders immediately. It is faster and cheaper for them to pick up supplies at a local Gariner outlet than to wait for delivery.

Tightly integrating the site and stocking locations not only increases the overall value to customers, it reduces Grainer’s costs as well. It is inherently more efficient took take and process order over the Web than to use traditional methods, but more efficient to make bulk deliveries to a local stocking location than to ship individual orders from a central warehouse.

Grainger has also found that its printed catalog bolsters its on-line operation. Many companies’ first instinct is to eliminate printed catalogs once their content is replicated on-line. But Grainger continues to publish its catalog, and it has found that each time a new one is distributed, one-line order surge. The catalog has proven to be a good tool for promoting the Web site while continuing to be a convenient way of packaging information for buyers.

In some industries, the use of the Internet represents only a modest shift from well-established practices. For catalog retailers like Lands’ End, providers of electronic data interchange services like General electric, direct marketers like Geico and Vanguard, and many other kinds of companies, Internet business looks much the same as traditional business. In these industries, established companies enjoy particularly important synergies between their on-line and traditional operations, which make it especially difficult for dot-coms to complete.

Examining segments of industries with characteristics similar to those supporting on-line businesses – in which customers are willing to forgo personal service and immediate delivery in order to gain convenience or lower prices, for instance- can also provide an important reality check in estimating the size of the Internet opportunity. In the prescription drug business, for example, mail orders represented only about 13% of all purchases in the late 1990s. Even though on-line drugstores may drawn more customers than the mail-order channel, it is unlikely that they will supplant their physical counterparts.

Virtual activities do not eliminate the need for physical activities, but often amplify their importance. The complementarily between Internet activities and traditional activities arises for a number of reasons. First, into ducting Internet applications in one activity often place greater demands on physical activities elsewhere in the value chain. Direct ordering, for example, makes warehousing and shipping more important.

Second, using the Internet in one activity can have systemic consequences, requiring new or enhanced physical activities that are often unanticipated. Internet-based job-positing services, for example, have greatly reduced the cost of reaching potential job applicants, but they have also flooded employers with electronic resumes. By making it easier for job seekers to distribute resumes, the Internet forces employers to sort through many more unsuitable candidates.

The added back -end costs, often for physical activities, can end up outweighing the up-front savings. A similar dynamic often plays out in digital marketplaces. Suppliers are able to reduce the transactional cost of taking order s when they move on-line, but they often have to respond to many additional requests for information and quotes, which, again, places new strains on traditional activities. Such systemic effects underscore the fact that Internet applications are not stand-alone technologies; they must be integrated into the overall value chain.

Third, most Internet applications have some short-comings in comparison with conventional methods, while Internet technology can do many useful things today and will surely improve in the future, it cannot do everything.

Its limits include the following:

1. Customers cannot physically examine, touch, and test products or get hands-on help in using or repair in them.

2. Knowledge transfer in restricted to codified knowledge, sacrificing the spontaneity and judgment that can result from interaction with skilled personnel.

3. The ability to learn about suppliers and customers (beyond their mere purchasing habits) is limited by the lack of fact-to face contract.)

4. The lack of human contract with the customer eliminates a powerful tool for encouraging purchases, trading off terms and conditions, providing advice and reassurance, and closing deals.

5. Delays are involved in navigating sites and finding information and are introduced by the requirement for direct shipment.

6. Extra logistical costs are required to assemble, pack and move small shipments.

7. Companies are unable to take advantage of low-cost, non-transactional functions performed by sales forces, distribution channels, and purchasing departments (such as performing limited services and maintenance functions at customers site.)

8. The absence of physical facilities circumscribes some functions and reduces a means to reinforce image and establish performance.

9. Attracting new customers is difficult given the sheer magnitude of the available information and buying options.

Traditional activities, often modified is some way, can compensate for these limits, just as the shortcomings of traditional methods- such as lack of real-time information, high cost of fact-to fact interaction, and high cost of producing physical versions of information- can be offset by Internet methods. Frequently, in fact, an Internet application and a traditional method benefit each other.

For example, many companies have found that Web sites that supply product information and supply direct ordering make traditional sales forces more, not less, productive and valuable. The sales force can compensate for the limits of the site by providing personalized advice and after sales service, for instance. On the site can make the sales force more productive by automating the exchange of routine information and serving as an efficient new conduit for leads. The fit between company activities, a cornerstone of strategic positioning, is in this way strengthened by the deployment of Internet technology.

Once managers begin to see the potential of the Internet as a complement rather than cannibal, they will take a very different approach to organizing their on-line efforts. Many established companies, believing that the new economy operated under new rules, set up their Internet operations in stand-alone units. Fear of cannibalization, it was argued, would better the mainstream organization from deploying the Internet aggressively. A separate unit was also helpful for investor relations, and it facilitated IPOs, tracking stocks, and spin-offs, enabling companies to tap into the market’s appetite for Internet ventures and provide special incentives to attract Internet talent.

But organizational separation, while understandable, has often undermined companies’ ability to gain competitive advantages. By creating separate Internet strategies instead of integrating the Internet into an overall strategy, companies filed to capitalize on their traditional assets, reinforced me-too competition, and accelerated competitive convergence. Barnes & Noble’s decision to establish Barnesandnoble(dot)com as a separate organization is a vivid example. It deterred the on-line store from capitalizing on the many advantages provided by the network of physical stores, thus playing into the hand of Amazon.

Rather than being isolated, Internet technology should be the responsibility of mainstream units in all parts of a company. With support from IT staff and outside consultants, companies should use the technology strategically to enhance service, increase efficiency, and leverage existing strengths. While separate units may be appropriate in some circumstances, everyone in the organization must have an incentive to share in the success of Internet deployment.

Essay # 9. The End of New Economy:

The Internet, then, is often not disruptive to existing industries or established companies. It rarely nullifies the most important sources of competitive advantage in an industry; in many cases it actually makes those sources even more important. As all companies come to embrace Internet technology, moreover, the Internet itself will be neutralized as a source of advantage.

Basic Inter applications will become table stakes- companies will not be able to survive without them, but they will not gain any advantage from them. The more robust competitive advantages will arise instead from traditional strengths such as unique products, proprietary content, distinctive physical activities, superior product knowledge, and strong personal service and relationships. Internet technology may be able to fortify those advantages, by tying a company’s activities together in a more distinctive system, but it is unlikely to supplant them.

Ultimately, strategies that integrate the Internet and traditional competitive advantages and ways of competing should win in many industries. On the demand side, most buyers will value a combination of on-line services, personal services, and physical locations over stand-alone Web distribution. They will want a choice of channels, delivery options, and way of dealing with companies.

On the supply side, production and procurement will be more effective if they involve a combination of Internet and traditional methods, tailored to strategy. For example, customized, engineered inputs will be brought directly, facilitated by Internet tools. Commodity items may be purchased via digital markets, but purchasing experts, supplier sales forces, and stocking locations will often also provide useful, value-added services.

The value of integrating traditional and Internet methods creates potential advantage for established companies. It will be easier for them to adopt and integrate traditional once. It is not enough, however, just to graft the Internet onto historical ways of competing in simplistic “clicks -and – mortar” configurations. Established companies will be most successful when they deploy Internet technology to reconfigure traditional activities or when they find new combinations of Internet and traditional approaches.

Dot-coms, first and foremost, must pursue their own distinctive strategies, rather than emulate one another or the positioning of established companies. They will have to break away from competing solely on price and instead focus on product selection, product design, service, image, and other area in which they can differentiate themselves. Dot-coms can also drive the combination of Internet and traditional methods.

Some will succeed by creating their own distinctive way of doing so. Others will succeed by concentrating on market segments that exhibit real trade-offs between Internet and traditional methods- either those in which a pure Internet approach best meets the needs of a particular set of customers or those in which a particular product or service can be best delivered without the need for physical assets. These principles are already manifesting themselves in many industries, as traditional leaders reassert their strengths and dot-com adopt more focused strategies. In the brokerage industry, Charles Schwab has gained a large share (18% at the end of 1999) of on-line trading than E-Trade (15%). In commercial banking, established institutions like Wells Fargo, Citibank, and fleet have many more on-line accounts than Internet banks do. Established companies are also gaining dominance over internet activities in such areas as retailing financial information, and digital marketplaces.

The most promising dot-coms are leveraging their distinctive skills to provide real value to their customers. E- college, for example, is a full-service provider that works with universities to required delivery network for a free. It is vastly more successful that competitors offering free sites to universities under their own brand names, hoping to collect advertising fee and other ancillary revenue.

When seen in this light, the “new economy” appears less like a new economy than like an old economy that has access to a new technology. Even the phrases “new economy” and “old economy” are rapidly losing their relevance, if they ever had any. The old economy of established companies and the new economy of dot-coms are merging, and it will soon be difficult to distinguish them. Retiring these phrases can only be healthy because it will reduce the confusion and muddy thinking that have been so destructive of economic value during the Internet’s adolescent years.

In our quest to see how the Internet is different, we have failed to see how the Internet is the same. While a new means of conducting business has become available, the fundamentals of competition remain unchanged. The next stage of the Internet’s evolution will involve a shift in thinking from e-business to business, from e-strategy to strategy. Only by integrating the Internet into overall strategy will this powerful net technology become an equally powerful force for competitive advantage.

Essay # 10. Words for the Unwise on the Internet:

Destructive Lexicon:

The misguided approach to competition that characterizes business on the Internet has even been embedded in the language used to discuss it. Instead of talking in terms of strategy and competitive advantage, dot-com and other Internet players talk about “business models” This seemingly innocuous shift in terminology speaks volumes. The definition of a business mode is murky at best.

Most often, it seems to refer to a loose conception of how a company does business and generates revenue. Yet simply having a business model is an exceedingly low bar to set for building a company. Generating revenue is a far cry from creating economic value, and no business model can be evaluated independently of industry structure. The business model approach to management becomes an invitation for thinking and self -delusion.

Other words in the Internet lexicon also have unfortunate consequences. The terms “e-business” and “e-strategy” have been particularly problematic. By encouraging managers to view their Internet operations in isolation from the rest of the business, they can lead to simplistic approaches to competing using the Internet and increase the pressure for competitive imitation. Established strategies and thus never harness their most important advantages.

Essay # 11. The Internet and the Value Chain:

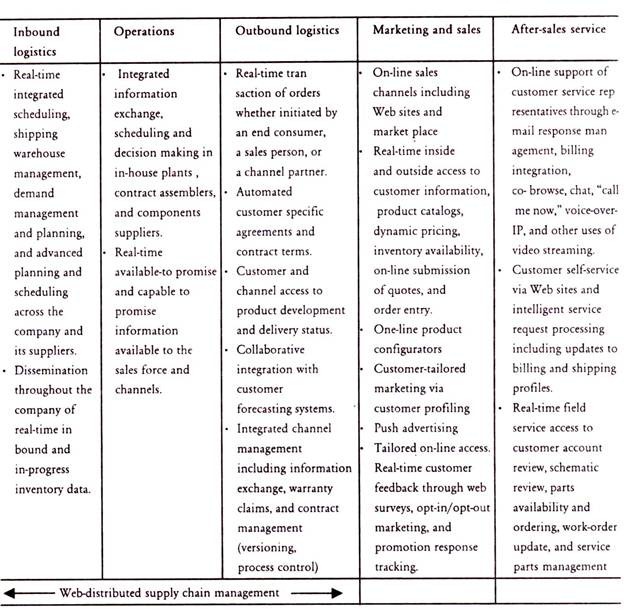

The basic tools for understanding the influence of information technology on companies is the value chain-the set of activities through which a product or service is created and delivered to customers. When a company competes in any industry, it performs a number of discrete but interconnected value-creating activities, such as operating a sales force, fabricating a component, or delivering products, and these activities have points of connection with the activities of suppliers, channels and customers. The value chain is a framework for identifying all these activities and analyzing how they affect both a company’s costs and the value delivered to buyers.

Because every activity involves the creation, processing, and communication of information, information technology has a pervasive influence on the value chain. The special advantage of the Internet is the ability to link one activity with others and make real-time data created in one activity widely available, both within the company and with outside suppliers, channels, and customers. By incorporating a common, open set of communication protocols, Internet technology provides a standardized infrastructure, an intuitive browse interface from information access and delivery, bidirectional communication, and ease of connectivity – al at much lower cost than private networks and electronic data interchange, or EDI.

Many of the most prominent applications of the Internet in the value chain are shown in the figure of that little. Some involve moving physical activities on-line, while others involve making physical activities more cost effective.

But for all its power, the Internet does not represent a break from the past; rather, it is the latest stage in the ongoing evolution of information technology. Indeed, the technological possibilities available today derive not just from the Internet architecture but also from complementary technological advances such as scanning, object-oriented programming, relational databases, and wireless communications.

To see how these technological improvements will ultimately affect the value chain, some historical perspective is illuminating. The evolution of information technology in business can be through of in terms of five overlapping stages, each of which evolved out of constraints presented by the previous generation.

The earliest IT systems automated discrete transactions such as order entry and accounting, the next stage involved the fuller automation and functional enhancement of individual activities such as human resource management, sales force operations, and product design, the third stage, which is being accelerated by the Internet, involves cross-activity integration, such as linking sales activities with order processing.

Multiple activities are being linked together through such tools as customer relationship management (CRM), supply chain management (SCM), and enterprises resource planning (ERP) systems, the fourth stage, which is just beginning, enables the integration of the value chain and entire value system, that is, the set of value chains in an entire industry, encompassing those of tiers of suppliers, channels and customers.

SCM and CRM are starting to merge, as end-to-end applications involving customers, channels, and supplier link orders to, for example, manufacturing, procurement, and service delivery. Soon to be integrated is product development, which has been largely separate. Complex product models will be exchanged among parties, and Internet procurement will move from standard commodities to engineered items.

In the upcoming fifth stage, information technology will be used not only to connect the various activities and players in the value system but to optimize it’s working in real time. Choices will be made based on information from multiple activities and corporate entities. Production decisions, for example, will automatically factor in the capacity available at multiple suppliers.

While early fifth-stage applications will involve relatively simple optimization of sourcing, production, logistical, and servicing transactions, the deeper levels of optimization will involve the product design itself. For example, product design will be optimized and customized based on input not only from factories and suppliers but also from customers.

Essay # 12. Prominent Applications of the Internet in the Value Chain:

A. Firm Infrastructure:

1. Web-Based, distributed financial and ERP systems.

2. One line investor relations (e.g., information dissemination, broadcast conference calls) Human resources,

1. Self-Service personnel and benefits administration,

2. Web-Based training,

3. Internet-Based sharing and dissemination of company information,

4. Electronic time and expenses reporting.

B. Human Resource:

1.Self-service personnel and benefits administration,

2.Web-based training,

3.Internet-based sharing and dissemination of company information,

4.Electronic time and expenses reporting.

C. Technology Development:

1. Collaborative product design across locations and among multiple value-system participants,

2. Knowledge directories accessible from all parts of the organization,

3. Real -time access by R&D to on-line sales and service information.

D. Procurement:

1. Internet-enabled demand planning; real-time available to promise/ capable-to promise and fulfillment,

2. Other linkage of purchase, inventory, and forecasting systems with suppliers,

3. Automated “requisition to pay”,

4. Direct and indirect procurement via market places, exchanges, quotations, and buyer-seller matching.

The power of the Internet in the value chain, however, must be kept in perspective. While Internet applications have an important influence on the cost and quality of activities, they are neither the only nor the dominant influence. Conventional factors such as scale, the skills of personnel, product and process technology, and investment in physical assets also play prominent roles. The Internet is transformational in some respects, but many traditional sources of competitive advantage remain intact.

Essay # 13. The Future of Internet Competition among Industries:

While each industry will evolve in unique ways, an examination of the force influencing industry structure indicates that the deployment of Internet technology will likely continue to put pressure on the profitability of many industries, consider the intensity of competition, for example.

Many dot-coms are going out of business, which would seem to indicate that consolidation will take place and rivalry will be reduced. But while some consolidation among new players is inevitable, many established companies are now more familiar with Internet technology and are rapidly deploying on-line applications.

With a combination of new and old companies and generally lower entry barriers, most industries will likely end up with a net increase in the number of competitors and fiercer rivalry than before the advent of the Internet.

The power of customers will also tend to rise. As buyers’ initial curiosity with the Web wanes and subsidies end, companies offering products or services on-line will be forced to demonstrate that they provide real benefits. Already, customers appear to be losing interest in services like Priceline, com’s reverse auctions because the savings they provide are often outweighed by the hassles involved. As customers become more familiar with the technology, their loyalty to their initial suppliers will also decline; they will realize that the cost of switching is low.

A similar shift will affect advertising – based strategies. Even now, advertisers are becoming more discriminating, and the rate of growth of Web advertising is slowing. Advertisers can be expected to continue to exercise their bargaining power to push down rates significantly, aided and abetted by new brokers of Internet advertising.

Not all the news is bad. Some technological advances will provide opportunities to enhance profitability. Improvements in streaming video and greater availability of low-cost bandwidth, for example, will make it easier for customer service representative, or other company personnel, to speak directly to customers through their computers, Internet sellers will be able to better differentiate themselves and shift buyers’ focus away from price. And services such as automatic bill paying by banks may modestly boost switching costs. In general however, new Internet technologies will continue to erode profitability by shifting power to customers.

To understand the importance of thinking through the longer-term structural consequence of the Internet, consider the business of digital market places. Such market places automate corporate procurement by linking many buyers and suppliers electronically.

The benefits to buyers include lower transaction costs, easier access to price and product information, convenient purchase of associated services, and, sometimes include lower selling costs, lower transaction costs, access to wider markets, and the avoidance of powerful channels.

From an industry structure standpoint, the attractiveness of digital marketplaces varies depending on the products involved. The most important determinant of a marketplace’s profit potential is the intrinsic power of the buyers and sellers in the particular product are. If either side is concentrated or processes differentiated products, it will gain bargaining power over the market place and capture most of the value generated.

If buyers and seller are fragmented, however, their bargaining power will be weak, and the marketplace will have a much better chance of being profitable, another important determinant of industry structure is the threat of substitution. If it is relatively easy for buyers and sellers to transact business directly with one another, or to set up their own dedicate markets, independent market places will be unlikely to sustain high levels of profit. Finally, the ability to create barriers to entry is critical.

Today, with dozens of marketplaces competing in some industries and with buyers and sellers dividing their purchase or operating their own markets to prevent any one marketplace from gaining power, it is clear that modest entry barriers are a real challenge to profitability.

Competition among digital marketplace is in transition, and industry structure is evolving. Much of the economic value crated by marketplace derives from the standards they establish, both in the underlying technology platform and in the protocols for connecting and exchanging information. But once these standards are put in place, the added value of the marketplace may be limited.

Anything buyers or suppliers provide to a marketplace, such as information on order specifications or inventory availability, can be readily provided on their own proprietary sites. Suppliers and customers can begin to deal directly on-line without the need for an intermediary. And new technologies will undoubtedly make it easier for parties to search for and exchange goods and information with one another.

In some product areas, marketplaces should enjoy ongoing advantages and attractive profitability. In fragmented industries such as real estate and furniture, for example, they could prosper. And new kinds of value added services may arise that only an independent marketplace could provide.

But in many product areas, marketplaces may be super cede by direct dealing or by the unbundling of purchasing, information, financing, and logistical services; in other areas, they may be taken over by participants or industry association as cost centers.

In such cases, marketplaces will provide a valuable “public good” to participants but will not themselves be likely to reap any enduring benefits. Over the long haul, moreover, we may well see many buyers back away from open market places. They may once again focus on building close, proprietary relationship with fewer suppliers, using Internet technologies to gain efficiency improvements in various aspects of those relationships.