Here is an essay on the ‘Rules for Succeeding in Business’ especially written for school and college students.

Rules for Succeeding in Business

Essay Contents:

- Essay on Zeroing in Key Processes in Business

- Essay on the three Approaches to Strategy in Business

- Essay on the Simple Rules for Unpredictable Markets in Business

- Essay on the Number of Rules Matters in Business

- Essay on the Creation of Rules in Business

- Essay on Knowing When to Change in Business

- Essay on the Exceptions to Simple Rules in Business

- Essay on Enron: Simple Rules and Opportunity Logic in Business

Essay # 1. Zeroing in Key Processes in Business :

Companies that rely on strategy as simple rules are often accused of lacking strategies altogether. Critics have derided AOL as “the cockroach of the Internet” for scurrying form one opportunity to the next. Some analysts accuse Enron of doing the same thing. From the outside, companies like these certainly appear to be following an “if it works, anything goes” approach.

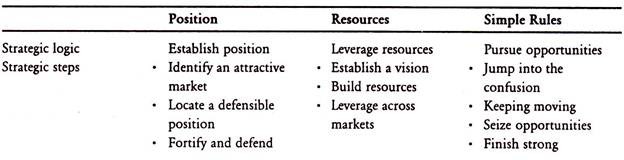

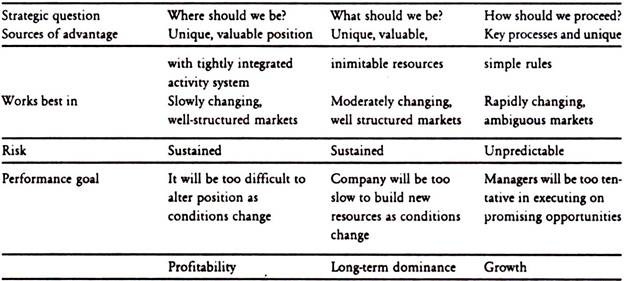

But that couldn’t be further from the truth. Each company follows a disciplined strategy-otherwise, it would be paralyzed by chaos. And, as with the effective strategies, the strategy is unique to the company. But a simple – rules strategy and its underlying logic of pursuing opportunities are harder to see than traditional approaches. (The exhibit “Three Approaches to Strategy” compares the strategies of position, resources, and simple rules.).

Managers using this strategy pick a small number of strategically significant processes and craft a few simple rules to guide them. The key strategic processes should place the company where the flow of opportunities is swiftest and deepest. The processes might include product innovation, partnering, spinout creation, or new market entry. For some companies, the choices are obvious-sum Microsystems focus on developing new products is a good example. For other companies, the selection of key processes might require some creativity – Akamai, for instance, has developed a focus on customer care. The simple rules provide the guidelines within which managers can pursue opportunities. Strategy, then, consists of the unique set of strategically significant processes and the handful of simple rules that guide them.

Essay # 2. Three Approaches to Strategy in Business :

Managers competing in business can choose among three distinct ways to fight. They can build a fortress and defend it; they can nature and leverage unique resources; or they can flexible pursue fleeting opportunities within simple rules. Each approach requires different skill sets and works best under different circumstances.

Autodesk, the global leader in software for design professional, illustrates strategy as simple rules. In the mid-1990s ,Autodesk’s markets were mature, and the company dominated all them. As a result, growth slowed to single-digit rates CEO Carol Bartz was sure that her most-promising opportunities lay in making use of those Autodesk technologies – in areas such as wireless communications, the Internet, imaging and global positioning -that hadn’t yet been exploited.

But she wasn’t sure which new technologies and related products would be big winners. So she refocused the strategy on the product innovation process and introduced a simple, radical rule: the new -product development schedule would be short ended from a leisurely 18 to 24 months to, in some cases, a hyper kinetic three months. That changed the pace, scale and strategic logic with which Autodesk tackled technology opportunities.

While a strategy of accelerating product innovation helped identify opportunities more quickly, Bartz lacked the cash to commercialize all the Autodesk’s promising technologies. So she added a significant net strategy: spinouts. The first spinout, Buzzsaw(dot)com, debuted in 1999. It allowed engineers to purchase contraction materials using B2B exchange technology. Buzzsaw(dot)com attracted significant venture capital and benefited from Autodesk’s powerful brand and its customer relationship. Autodesk has since created a second spinout, Red spark, and has developed simple rules for the new key process of spinning off companies.

A company’s particular combination of opportunities and constrains often dictates the processes it chooses. Cisco, Autodesk, Lego, and Yahoo! Began with strategies in which product innovation was dominant, but their emphases diverged. Cisco’s new opportunities lay in the many new networking technologies that were emerging but the company lacked the time of engineering talent to develop them all.

In contract to technology-rich and stock-price- poor Autodesk, which focused on spinouts Cisco-with high market capitalization- found that acquisitions was the way to go. Despite its stratospheric market cap, Yahoo! Went in yet another direction. The company wanted to exploit content and commerce opportunities but needed a lot of partners. Many were too big to acquire, so it created partnerships. Lego’s best opportunities were in extending its power brand and philosophy into markets. But since the company faced less competition and operated at a slower pace than Autodesk, Cisco, or Yahoo! Managers could grow organically into new product markets such as children’s robotics, clothing, theme parks, and software.

Essay # 3. Simple Rules for Unpredictable Markets in Business :

Most managers quickly grasp the concept of focusing on key strategic processes that will position their companies were the flow of opportunities is most promising. But because they equate processes with detailed routines, they often miss the notion of simple rules. Yet simple rules are essential. They poise the company on what’s termed in complexity theory “the edge of chaos,” providing just enough structure to allow it to capture the best opportunities. It may sound counterintuitive, but the complicated improvisational movements that companies like AOL and Enron make as they pursue fleeting opportunities arise from simple rules.

Yahoo’s managers initially focused their strategy on the branding and product innovation processed and lived by four product innovation rules know the priority rank of each product in development, ensure that every engineer can work on every project, maintain the Yahoo! Looking the user interface, and launch products quietly. As long as they followed the rules, developers could change products in any way they chose, come to work at any hour, were anything, and bring along their dogs and significant others.

One developer decided at midnight to build a new spots page covering the European soccer champion-ships. Within 48 hours, it become Yahoo’s most popular page, with one more than 100,000 hits per day. Since he knew which lines he had to stay within, he was free to run with a great idea when it occurred to him. A day later, he was back on his primary project. On a bigger scale, the simple rules, in particular the requirement that every engineer be able to work on every project, allowed Yahoo!’ to change 50% of the code for the enormously successful. My Yahoo Service launched four weeks before to adjust to the changing market.

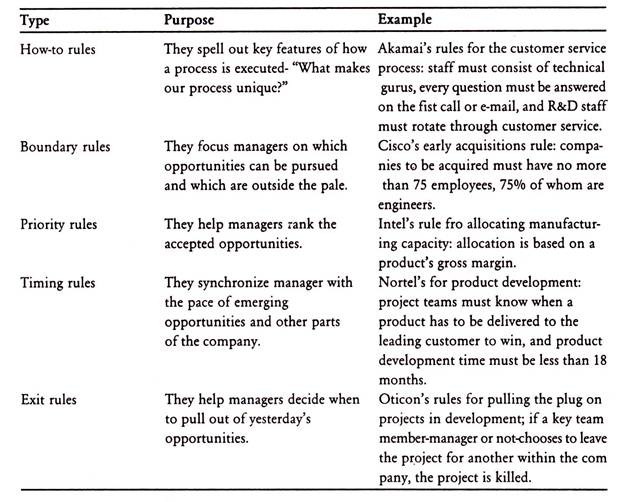

Over the course of studying dozens of companies in turbulent and unpredictable markets, we’ve discovered that the simple rules fall into five broad categories. (See the exhibit “Simple Rules, Summarized.”).

Simple Rules, Summarized:

In turbulent markets, managers should flexible seize opportunities- but flexibility must be disciplined. Smart companies focus on key processes and simple rules. Different types of rules help executives manage aspects of seizing opportunities.

i. How to Rule:

Yahoo’s how-to rules kept managers just organized enough to seize opportunities. Enron provides another how-to example. Its commodities -trading business focuses strategy on the risk management process with two rules: each trade must be offset by another trade that allow the company to hedge its risk, and every trader must complete a daily profit and loss statement. Computer giant Dell focuses on the process of repaid reorganization (or patching) around focused customer segments, a key how-to rue for this process is that a business must be split in two when its revenue hit $1 billion.

ii. Boundary Rules:

Sometimes simple rules delineate boundary conditions they help managers sort though many opportunities quickly. They rules might center on customers, geography, or technologies. For example, when Cisco first moved to an acquisitions -let strategy, its boundary rule was that it could acquire companies with at most 75 employees, 75% of whom were engineers.

At a major pharmaceutical company, strategy centers on the drug discovery process and several boundary rules: researchers can work on any often molecules (no more than four at once) specified by a senior research committee, and a research project must pass a few continuation hurdles related to progress in clinical trials. Within those boundaries, researchers are free to pursue whatever looks promising. The result has been drug pipeline that’s the envy of the industry.

Miramax- well known for artistically innovative movies such as; the crying game, Life is Beautiful, and Pulp fiction has boundary rules that guide the al important movie-picking process: first, ever movies must revolve around a central human condition, such as love (The crying game) or envy (The Talented Mr. Ripley).

Second, a movie’s main character must be appealing but deeply flawed – the hero of Shakespeare in Love is gifted and charming but steals ideas from friends and betrays his wife, third, movies must have a very clear story line with a beginning, middle, and end (although in Pulp Fiction the end comes first).

Finally, there is a firm cap on production costs. Within the rules, there is flexibility to move quickly when a writer or director shows up with a great script. The result is an enormously creative and even surprising flow of movies and enough discipline to produce superior, consistent financial results. The English Patient, for example, cost $27 million to make, grossed more than $200 million, and grabbed nine Oscars.

Lego provides another illustration of boundary rules. At Lego, the product market-entry process is a strategic focus because of the many opportunities to extend the Lego brand and philosophy. But while there is plenty of flexibility, not every market makes the cut. Lego has a checklist or rules.

Does the proposed product have the Lego look? Will children learn while having fun? Will parents approve? Does the product maintain high quality standards? Does it stimulate creativity? If an opportunity falls short on one hurdle, the business team can proceed, but ultimately the hurdle must be cleared, Lego children’s wear, for example, met all the criteria except one: it didn’t stimulate creativity. As a result, the members of the children’s were them team worked until they figured out the answer- a line of mix-and-match clothing items that encouraged children to create their own fashion statements.

iii. Priority Rules:

Simple rules can set priorities for resource allocation among competing opportunities. Intel realized a long time ago that it needed to allocate manufacturing capacity amount its products very carefully, given the enormous costs of fabrication facilities. As a time of extreme price volatility in the mid -1980s, when Asian chip manufacturers were disrupting world markets with severe price cuts and accelerated technological improvement Intel followed a simple rule: allocate manufacturing capacity based on a product’s gross margin. Without this rule, the company might have continued to allocate too much capacity to its traditional core memory business rather than seizing the opportunity to dominate the nascent and highly profitable microprocessor niche.

iv. Timing Rules:

Many companies have timing rules that set the rhythm of key strategic processes. In fact, pacing is one of the important element that set simple-rules strategies apart from traditional strategies. Timing rules can help synchronize a company with emerging opportunities and coordinate the company’s various parts to capture them. Nortel networks now relies on two timing rules for its strategically important product innovation process: project teams must always know when a product has to be delivered to the leading customer to win, and product development time must be less than 18 months.

The first rule keeps Nortel in sync with cutting-edge customers, who represent the best opportunities. The second forces Nortel to move quickly into new opportunities while synchronizing the various parts of the corporation to do so. Together, the rules helped the company shift focus from perfecting its current products to exploiting market openings to “go from perfection to hitting market windows,” as CEO John Roth puts it.

At an Internet based service company where we worked, globalization was the process that put the company squarely in the path of superior opportunities. Managers drove new-country expansion at the rate of one new country every two months, thus maintaining constant movement into new opportunities. Many top Silicon Valley companies set timing rules for the length of the product innovation process. When developers approach a deadline, they drop features to meet the schedule. Such rhythms maintain movement and ensure that the market and various groups within the origination – from manufacturing to marketing to engineering – are on the same beat.

v. Exit Rules:

Exit rules help managers pull out from yesterday’s opportunities. At the Danish hearing -and company Oticon, executives pull the plug on a product in development if a key team member leaves for another project. Similarly, at a major high-tech multinational where creating new businesses is a key strategic process, senior executives stop new initiatives that don’t meet certain sales and profit goals within two years.

Essay # 4. The Number of Rules Matters in Business :

Obviously, it’s crucial to write the right rules. But it’s also important to have the optimal number of rules. Thick manual of rules can be paralyzing. Then can keep managers from seeing opportunities and moving quickly enough to capture them. We worked with a computer marker, for example, whose minutely structured process for product innovation was highly efficient but left the company flexibility to respond to market changes. On the other hand, too few rules can also paralyze.

Managers chase too many opportunities or become confused about which to pursue and which to ignore. We worked with Biotech Company that lagged behind the competition in forming successful partnership, a key strategic process in that industry. Because the company lacked guidelines, development managers brought in deal after deal and key scientists were pulled from clinical trials over and over again to perform due diligence.

Senior management ended up rejecting most of the proposal, Executives may have had implicit rules, but nobody knew what they were. One business development manager lamented: “It would be so liberating if only I had a few guidelines about what I’m supposed to be looking for.” While creating the right number of rules – it’s usually somewhere between two and seven – is central, companies arrive at the optimal number from different directions.

On the one hand, young companies usually have too few rules, which prevents them from executing innovating ideas effectively. They need more structure, and they often have to build their simple rules from the ground up. On the other hand, older companies usually have too many rules, which keep them from competing effectively in turbulent markets. They need to throw out massively complex procedures and start over with a few easy-to -follow directives.

The optimal number of rules for a particular company can also shift over time, depending on the nature of the business opportunities. In a period of predictability and the opportunities more diffuse, it makes sense to have fewer rules in order to increase flexibility. When Cisco started to acquire aggressively, the “75 people, 75% engineers” rules worked extremely well – it ensured a match with Cisco’s entrepreneurial culture and left the company with lots of space to maneuver.

As the company developed more clarity and focus in its home market, Cisco recognized the need for a few more rules; a target must share Cisco’s vision of where the industry is headed, it must have potential for short-term wins with current products it must have potential for long-term wings with the following on product generation, it must have geographic proximity to Cisco, and its culture must be compatible with Cisco’s If a potential acquisition meets all five criteria, it gets a green light.

If it meets four, it gets a yellow light – further consideration is required. A candidate that meets fewer than four gets a red light. CEO John Chambers believes that observing these simple rules has helped Cisco resist the temptation to make inappropriate acquisitions. More recently, Cisco has relaxed its rules (especially on proximity) to accommodate new opportunities as the company moves further afield into new technologies and toward new customers.

Essay # 5. Creation of Rules in Business :

We’re often asked where simple rules come from. While it’s appealing to think that they arise from clever thinking, they rarely, do. More often, they grow out of experience, especially mistakes. Take Yahoo! And its partnership – certain rules. An exclusive joint venture with a major credit card company proved calamitous. The deal locked Yahoo! into a relationship with particular firm, thereby limiting e-commerce opportunities. After an expensive exit, Yahoo! Developed two simple rules for partnership creation: deals can’t be exclusive, and the basic service is always free.

At young companies, where there is no history to learn form, senior executive use experience gained at other companies. CEO George Conrades of Akamai, for example drew on his decades of marketing experience to focus his company on customer service – a surprising choice of strategy for a high-tech venture.

He then declared some simple rules: the company must staff the customer service group with technical gurus, every question must be answered on the first call or e-mail, and R&D people must rotate through customer care. These how-to rules shaped customer service at Akamai but left plenty of room for employees to innovate with individual customers.

Most often, a rough outline of simple rules already exists in some implicit form. It takes an observant manager to make them explicit and then extend them as business opportunities evolve by examining how its simple rules have been applied over time.) EBay, for example, started out with strong values: egalitarianism for the rest of us. “Over time, founder and chairman Pierre Omidyar and CEO Meg Whitman made those values explicit in simple rules that helped manager predict which opportunities would work for eBay.

Egalitarianism evolved into two simple how-to rules for running auctions: the number of buyers and sellers must be balanced, and transactions must be as transparent as possible. The first rule equalizes the power of buyers and sellers but does not restrict who can participate, so the eBay site is open to everyone, from individual collectors to corporations (indeed, several major retailers now use eBay as a quiet channel tor their merchandise). The second rule gives all participants equal access to as much information as possible. This rule guide eBay managers into a series of moves such as creating feedback ratings on sellers, on-line galleries for expensive items, and authentication services from Lloyd’s of London.

The business meaning of community was crystallized into a few simple rules, too; product ads aren’t allowed (they compete with the community), prices for basic services must not be raised (increases hurt small members) and eBay must uphold high safety standards (a community needs to feel safe). The rules further clarified which opportunities made sense. For instance, it was okay to launch the Power Sellers program, which offers extra service for community members who sell frequently.

It was also okay to allow advertising by financial services companies and to expand into Europe, because neither move broke the rules or threatened the community. On the other hand, it was not okay to have advertising deals with companies such as CD now whose merchandise completes with the community. Only later did the economic value of the rules become apparent: the strength of the eBay community posed a formidable entry barrier to competitors, while egalitarianism created a high level of trust and transparency among traders that effectively differentiated eBay form its competitors.

It’s entirely possible for two companies to focus on the same key process yet develop radically different simple rules to govern it. Consider Ispat International and Cisco, in the last decade, Ispat has gone from running a single steel mill in Indonesia to being the fourth-largest steel company in the world by using a new- economy strategy in an old-economy business. Founder Lakshmi Mittal’s strategy centers on the acquisition process. But Ispat’s rules for acquisitions look a whole lot different from Cisco’s for the same process.

Ispat’s rules include buying established, state-owned companies that have problems. Cisco’s rules limit its acquisitions to young, well-run, VC-backed companies. Ispat’s rules don’t include geographic restrictions, so managers search the globe- Mexico, Kazakhstan, and Ireland- for ailing companies. At least initially, Cisco’s rules required exactly the opposite focus- the company stayed close to home with lots of acquisitions in Silicon Valley. Ispat focuses narrowly on two-process technologies- DRI and electric are furnaces- to drive companywide consistency.

At Cisco, the whole point is to acquire new technologies. Ispat’s rules center on finding companies in which costs can be cut from current operations. Cisco’s rules gauge revenue gains from future products. The bottom line; some strategic process, same entrepreneurial emphasis on seizing fleeting opportunities, some superior wealth creation- but with totally different simple rules.

Essay # 6. Knowing When to Change in Business :

It’s important for companies with simple -rules strategies to follow the rules religiously – think Ten Commandment, not optional suggestions – to avoid the temptation to change them too frequently. A consistent strategy help managers rapidly sort through all kinds of opportunities and gain short-term advantage by exploiting the attractive ones. More subtly, it can lead to patterns that build long-term advantage, such as Lego’s powerful brand position and Cisco’s interrelated networking technologies.

Although it’s unwise to churn the rules, strategies do go stale. Shifting the rules can sometimes rejuvenate strategy, but if the problems are deep, switching strategic processes may be necessary. The ability to switch to new strategic processes has been a success secret of the best new-economy companies.

For example, Inktomi, a leader in Internet infrastructure software, augmented its original strategic focus on the product innovation process with a focus on the market entry process and a few boundary rules: the company must never produce a hardware product, never interface directly with end users, and always develop software for applications with many users and transactions (this exploits Inktom’s basic technology). Company managers did not restrict the business or revenue models. The result was successful new businesses in, for example, search engines, cashing, and e-commerce engines. In fact, the company’s second business, cashing, is now its key growth driver.

But CEO Dave Peterschmidt and his team have recently turned their attention to the sales process because corporations a much bigger customer set than was available in their original portal market- are buying Inktomi software to manage intranets, thus opening a massive stream of new opportunities, inktomi is turning to this new opportunity flow and crafting fresh simple rules. Inktomi is thus accelerating growth by adding new processes before old one falter. If managers wait until the opportunity flow dries up before shifting processes, it’s already too late. (For more details on the use of simple rules over time, see “Enron: Simple Rules and Opportunity Logic” at the end of this article.).

Essay # 7. Exceptions to Simple Rules in Business :

It is most difficult to dictate exactly what a company’s simple rules should be. It is possible, however, to say what they should not be:

i. Broad:

Managers often confuse a company’s guiding principles with simple rules. The celebrated “HP way, “for example, consists of principles like “we focus on a high level of achievement and contribution” and “we encourage flexibility and innovation”. The principles are designed to apply to every activity within the company, from purchasing to product innovation, They may create a productive culture, but they provide little concrete guidance for employees trying to evaluate a partner or decide whether to enter a new market. The most effective simple rules, in contrast, are tailored to a single process.

ii. Vague:

Some rules cover a single process but are too vague to provide real guidance. One Western bank operating in Russia, for example, provided the following guideline for screening investment proposals: all investments must be currently undervalued and have potential for long-term capital appreciation, Imagine the plight of a newly hired associate who turns to that rules for guidance!

A simple screen can held managers test whether their rules are too vague. Ask: could any reasonable person argue the exact opposite of the rule? In the case of the bank in Russia, it is hard to imagine anyone suggesting that the company target overvalued companies with no potential for long-term capital appreciation. If your rules flunk this test, they are not effective.

iii. Mindless:

Companies whose simple rules have remained implicit may find upon examining them that these rules destroy rather than create value. In one company, managers listed their recent partnership relationships and then tried to figure out what rules could have produced the list. To their chagrin, they found that one rules seemed to be: always form partnership with small, weak companies that we can control. Another was: always form partnerships with companies that are not as successful as they once were. Again, use a simple test- reverse-engineer your processes to determine your implicit simple rules. Throw out the one that are embarrassing.

iv. Stale:

In high-velocity markets, rules can linger beyond their sell by dates. Consider Banc One. The Columbus, Ohio-based bank grew to be the seventh largest bank in the United States by acquiring more than 100 regional banks. Banc One’s acquisitions followed a set of simple rules that were based on experience: Banc One must never pay so much that earnings are diluted, it must only buy successful banks with established management team, it must never acquire a bank with assets greater than one-third of Banc One’s, and it must allow acquired bank to run as autonomous affiliates. The rules worked well until others in the banking industry consolidated operations to lower their costs substantially. Then Banc One’s loose confederation of banks was burdened with redundant operations, and it got clobbered by efficient competitors.

How do you figure out if your rules are stale? Showing growth is a good indicator. Stock price is even better. Investors obsess about the future, while your own financials reports the past. So if your share price is dropping relative to your competitors’ share prices, or if your percentage of the industry’s market value is declining, or if growth is slipping, your rules may need a refresh.

Essay # 8. Enron: Simple Rules and Opportunity Logic in Business :

Simple Rules establish a strategic frame-not a step-by-step recipe-to help managers seize fleeting opportunities. Few companies have following the logic of opportunity or the discipline of simple rules as consistently as Enron. Fifteen years ago, the company’s main line of business was interstate gas transmission-hardly a market space teeming with opportunities.

Today, Enron makes markets in commodities ranging from pulp and paper to pollution-emission allowances. It also controls an expansive fiber-optic network, and runs an on-line exchange Enron Online-whose daily trading volume ranks it among the largest e-commerce sites.

Enron began its remarkable transformation by embracing uncertainty. While conventional wisdom dictates the managers avoid uncertainly, the logic of opportunity dictates that they seek it out, like the outlaw Willie Sutton, who robbed banks because that’s where the money was, Enron managers embraced uncertainty because that’s where the juicy opportunities lay.

Enron’s managers expanded from their traditional pipeline business into wholesale energy distribution, trading and global energy. At a time when other energy executives where doggedly defending their regulatory protection, Enron CEO Ken Lay aggressively lobbied to accelerate deregulation in order to create new opportunities for Enron to exploit.

Once they had plunged into the brave new world of deregulated energy, Enron managers faced a challenge common to new-economy companies but rare among utilities-how to navigate among the overabundance of opportunities. To shift among opportunities, Enron mostly relied on small moves, which are faster and safer then large ones. Often, the moves were made from the bottom – many of Enron’s new trading businesses began as one-person operations.

The company needed to provide some structure for all this movement among opportunities. Enter key processes and simple rules. In Enron’s commodities-trading businesses, for example, strategy centers on the risk management process and two simple rules: all trades must be balanced with an of process and two simple rules: all trades must be balanced with an offsetting trade to minimize unhinged risk, and each trader must report a daily profit and loss statement.

As long as they follow these how-to rules, Enron’s traders are free to pursue new opportunities, the strategy has led the company to pioneer markets for commodities that had never been traded before including fiber-optic band with, pollution-emission credits, and weather derivatives- contracts that allow companies to hedge their weather-related risk.

When it comes to strategic processes and simple rules, one size doesn’t fit all. When Enron pioneered out sourced energy -management services in 1996, every organization with a high-energy bill was a potential customer. To select from the overwhelming number of opportunities, Enron managers focused on the customer screening process and articulated a few boundary rules to identify attractive customers: a target customer must have outsourced before, energy must not be core of its business, and contacts with Enron must already exist somewhere within the company.

In additional, Enron sales people must deal directly with the CEO or CFO, because only the top executives can assess the potential for companywide savings and then commit. In four years, Enron Energy Services has grown from nothing to $15 billion in sales.

When pursuing novel opportunities such as trading weather derivate and providing outsourced energy management, it’s impossible for Enron managers to predict which initiatives will take off. Managers must be prepared, therefore, to reinforce successful moves that gain traction, even if those successes run counter to managers’ preconceived notions of what should work. Fiber optic cable, for example, had little to do with Enron’s care energy business, but managers quickly recognized its potential and backed a winner.

In uncertain markets, not every opportunity pans out Savvy managers respond not by making fewer moves but by cutting their losses quickly, after Enron’s acquisition of Portland General failed to work out according to plan, the company quickly put the utility back on the block. Manager at Enron also try to build on mistakes by salvaging what did work and recombining it with other resources to create new opportunities.

This recombination works particularly well for large companies like Enron that have an abundance of “genetic material” – technologies, products, and expertise- for creative combinations. So while the Portland general acquisition as a whole failed to pan out, Enron managers salvaged the utility’s fledgling broadband cable business and combined it with Enron’s expertise in trading to create a host of new opportunities in buying and selling broadband capacity and running a fiber-optic network.

The Enron story also illustrates the importance of “finishing strong” when managers discover a huge opportunity. In chaotic markets, the initial move, no matter how masterful, rarely yields unambiguous success. Rather, initial moves unearth subsequent opportunities that may prove huge, as e-commerce and broadband cable have for Enron.

The key risks in pursuing uncertain opportunities are that moves may become too tentative – too prone to quick retreat – and that managers might grow overly cautious in pursuing the big opportunities that promise outsized payoffs. Enron has succeeded, in large part, because its managers finish strong. In broadband, the company reinforced early successes through moves such as delivering movies on demand in partnership with Blockbuster. Similarly, after Enron’s initial foray into Internet trading took off, top executives rapidly redeployed resources from throughout the company to scale Enron Online.