Here is an essay on ‘Eurocurrency Market’ for class 9, 10, 11 and 12. Find paragraphs, long and short essays on ‘Eurocurrency Market’ especially written for school and college students.

Essay Contents:

- Essay on the Introduction to Eurocurrency Market

- Essay on Eurocurrency Deposits and Loans

- Essay on Eurocurrency Market Versus the Foreign Exchange Market

- Essay on the Growth of the Eurocurrency Market

- Essay on the Regulation of Eurocurrency Market

- Essay on the International Financial Centres of Eurocurrency Market

Essay # 1. Introduction to Eurocurrency Market:

The savings of households, companies and government are channelled through the economy’s financial system and lent to the borrowers. The financial system functions within the supervision of regulatory bodies, such as SEBI, RBI, IRDA, PFRDA and the Ministry of Finance in India. Similarly, other countries also have their regulators. One of the significant developments in International Finance has been the creation of the Eurocurrency market. It is a wholesale market in which Eurocurrencies are borrowed and lent in multiples of $10 million. This article describes the evolution of the Eurocurrency market.

Eurocurrency:

Eurocurrency is a deposit at a bank (or the branch of a bank) outside the country of the currency in which that deposit is denominated. US dollars held by savers outside the USA are called euro dollars. Similarly, yen held by savers outside Japan are called Euro-yen. Thus, any currency that is held outside the country, in which it is legal tender, is called Eurocurrency.

Eurocurrency Market:

The Eurocurrency market is defined by Dufey and Giddy as ‘a market in which funds are intermediated outside the country of the currency in which the funds are denominated’, and by Pilbeam as ‘banking markets which involve short-term borrowing and lending conducted outside of the legal jurisdiction of the authorities of the currency that is used’. The Eurocurrency market is an external banking system (located in any country) consisting of euro banks, which are so called because they accept deposits and grant loans in a currency that is not the currency of the country in which it is located.

Eurocurrency Versus the Euro:

Eurocurrency is not the same as the euro which is the currency of the countries in the European Union that have adopted it as their national currency. The euro replaced the French Franc and the Deutschemark as legal tender.

On the other hand, Eurocurrency is a deposit in currency which is not legal tender of that country but is used for banking purposes—that is to accept deposits and make loans. Hence, a deposit of British pounds in a German bank is called a Euro-deposit. But a deposit of euros in a German bank is not a Euro-deposit. It is a deposit denominated in a currency called euro (recall that the euro is legal tender in Germany).

Similarly, if a Singapore-based bank accepts a deposit of euros by a British company, it would be a Euro-deposit because the euro is not legal tender in Singapore. It has nothing to do with the fact that the deposit is of euros. Thus, one must make a clear distinction between Eurocurrency and the euro.

Essay # 2. Eurocurrency Deposits and Loans:

How do savers hold Eurocurrency? As a deposit in a bank, US dollars or Japanese yen deposited in a bank in Australia are Eurocurrency deposits. Naturally, the bank will lend the dollars (as US dollar loans) and the yen (as yen loans) to borrowers in Australia. A Eurocurrency loan is a loan of Eurocurrency. What is important is the location of the bank (or its branch) and not the ownership of the deposit. But the Australian monetary authority only controls Australian dollar deposits and Australian dollar loans. It has no control over Eurocurrency deposits and Eurocurrency loans. Therefore, Eurocurrencies are borrowed and lent in the Eurocurrency market.

A Euro-bank is defined as ‘a financial intermediary that simultaneously bids for time deposits and makes loans in a currency, or currencies other than that of the country in which it is located.’ The term ‘Euro-bank’ does not refer to an institution—it actually describes a specific set of activities performed by a commercial bank. Any commercial bank that accepts Eurocurrency deposits and gives Eurocurrency loans is a Euro-bank. But the commercial bank also accepts deposits and grants loans in the currency of the country in which it is located.

Therefore, a euro-bank’s balance sheet consists of:

i. Deposits and loans in the currency of the country in which the bank is located.

ii. Deposits and loans in other currencies.

Eurobank, Eurocurrency and Europe:

The term ‘Euro ‘ in Eurocurrency and euro bank does not refer to the bank’s location—it has nothing to do with being located in Europe. The above example of a Singapore-based bank with Eurocurrency deposits shows that the bank holds Eurocurrency deposits (or makes Eurocurrency loan as the case may be). Financial centres in Europe, such as Luxembourg, have a very large number of Euro-banks and Europe remains an important centre of Euro-banking activity.

A currency-wise break up of a bank’s balance sheet is shown below. The first three rows reflect its domestic banking operations. Foreign currency deposits are those permitted by the banking laws of the country. For instance, an Indian citizen can make dollar deposits in an Indian bank. The bank’s pound-denominated deposits and loans (row 4) are from the London-based branch of the bank. Rows 5 to 7 show the yen, dollar and euro-denominated deposits and loans of the London-based branch. Since the yen, dollar and euro are not legal tender in Britain, they are Eurocurrency deposits and Eurocurrency loans.

Balance Sheet of an Indian bank with a branch in Great Britain:

Liabilities:

1. Capital (in rupees)

2. Rupee demand deposits

3. Rupee time deposits

4. Pound sterling deposits

5. Yen deposits

6. Dollar deposits

7. Euro deposits

Assets:

1. Cash (in rupees)

2. Rupee loans

3. Rupee investments

4. Pound sterling loans

5. Yen loans

6. Dollar loans

7. Euro loans

Essay # 3. Eurocurrency Market Versus the Foreign Exchange Market:

There are some crucial differences between the two markets even though both deal in currencies:

i. Participants in the Eurocurrency market are international banks. Participants in a country’s foreign exchange market are domestic banks and branches of foreign banks.

ii. The Eurocurrency market has no regulatory authority in the country in which it is operating, with respect to its Eurocurrency-denominated deposits and loans. But domestic commercial banks, branches of foreign banks, and the local currency-denominated deposits and loans of international banks are regulated by the central bank of the country—all rupee-denominated deposits and loans are regulated by the RBI, and the US dollar-denominated deposits and loans by the Federal Reserve.

iii. The Euro-market does not have any geographical limits. Its activities from anywhere in the world. But domestic commercial banks, and b banks operating in a particular country, can operate only within the geographical boundaries of that country.

iv. Wholesale transactions take place in the Eurocurrency market. But domestic commercial banks, and branches of foreign banks operating in a particular country, undertake wholesale as well as retail transactions.

Essay # 4. Growth of the Eurocurrency Market:

The term ‘Eurocurrency’ has an interesting history. The US dollar was a reserve currency under the Bretton Woods Agreement and many countries preferred to receive US dollars (many countries still do). But dollar deposits had to be held by an American bank. In the 1950s at the height of the Cold War, the Moscow Narodny Bank in Soviet Russia, and several Soviet bloc countries held their US dollar deposits (that is Eurodollars) in European banks, to avoid the potential threat that the United States would freeze dollar deposits if they were in a bank located in the United States.

Such concerns were not misplaced—political considerations made the USA freeze Iranian dollar deposits in 1979, Libyan dollar deposits in 1981, and Iraqi dollar deposits in 2003. But these isolated incidents served to merely lay the foundations for the birth of the Eurocurrency market. What are the factors that led to its meteoric growth since the 1950s? The Eurodollar market was the first and biggest constituent of the Eurocurrency market. Since the growth of the latter in the 1960s paralleled the rise of US balance of payments (BOP) deficits, it is tempting to ascribe the rise of the Eurocurrency market to the Balance Of Payments problems of the USA.

(i) In the 1950s and 1960s, the central banks of Britain and the United States imposed ceilings on activities of commercial banks.

(ii) In 1957, ceilings were imposed on the maximum loans that British commercial banks could make in pound sterling. But no such ceiling was imposed on the loans that British commercial banks could make in other currencies. British banks began to accept dollar deposits and make dollar loans.

(iii) In the USA, the Federal Reserve used moral suasion to restrict overseas lending by US banks and on the financing of FDI by US banks in 1965. This was replaced by legislation to that effect in 1968. A ceiling was placed on the maximum amount of dollar loans that a US MNC could take to finance its overseas expansion. This was called the Foreign Credit Restraint Program. Banks in the USA began to see the advantages of holding Eurocurrency deposits, and making Eurocurrency loans.

(iv) In 1963, an interest equalization tax was imposed on US investors who purchased securities overseas. Investors then began looking at ways to hold dollar deposits outside the USA.

(v) Interest rate ceilings (known as Regulation Q) were imposed on dollar deposits in American banks. An American bank was not permitted to offer an interest rate higher than the ceiling specified by the Federal Reserve. But banks outside the United States did not face such a restriction on any dollars deposited with them. Thus, dollar deposits began moving out of banks located in the United States and into banks located outside United States, principally Europe.

Therefore, the actions of savers, financial intermediaries and lenders to overcome restrictions imposed by monetary authorities were a significant factor in propelling the growth of the Eurocurrency market.

Accumulation of Dollar Reserves:

Under the Bretton Woods exchange rate system, which was created in 1944, the US dollar was given the status of a reserve currency. As a result, in the 1950s and 1960s, countries began to build huge dollar reserves. This was also the time when the reconstruction of Europe devastated by World War II was in full swing. As American corporations increasingly became multinational, they needed funds to finance their factories and operations all over the world. But the US government, concerned that the rest of the world was holding more and more US dollars, brought in several pieces of legislation to prevent US dollars from leaving the country.

This had the unintended consequence of making US MNCs approach banks based outside the USA for the dollar loans they needed for outbound FDI. These banks made the Eurodollar loans at interest rates that were lower than those offered on dollar loans by American banks. Even though the interest rate ceilings and ceiling on dollar borrowings were subsequently removed, the Eurocurrency market had developed well fuelled by borrowers and lenders.

Eurocurrency deposits do not attract reserve requirements, so bank spread is higher and the bank can pay a higher interest rate on such deposits. This attracted depositors. The domestic banking system in a country is required to adhere to reserve requirements namely cash reserve ratio (CRR) and statutory liquidity ratio (SLR) requirements stipulated by the monetary authority. If the CRR and SLR put together are 30%, it means that of every Rs. 100 of deposits received by a commercial bank, only Rs. 70 can be lent out by the bank.

For Eurodollar deposits, the bank can lend the entire $100, and can therefore pay a higher interest rate of 6.50%. When investors Ire free to move their deposits from one currency to another, they would prefer to hold Eurodollar deposits. Absence of reserve requirements on Eurocurrency deposits increases the overall return on investment (ROI) of a bank.

The bank can charge a lower interest rate on Eurocurrency loans. In the above example, the bank can charge 7% as interest on its Eurocurrency loans, compared to 8% on its rupee loans. This attracts borrowers. Thus, borrowers may switch currencies because Eurocurrency loans are cheaper. Borrowers have a wider menu in terms of the currency in which they borrow. In practice, the spreads on Eurocurrency are lower than the spreads on domestic currency activities of a bank simply because regulatory restrictions on Euro-banks are lower.

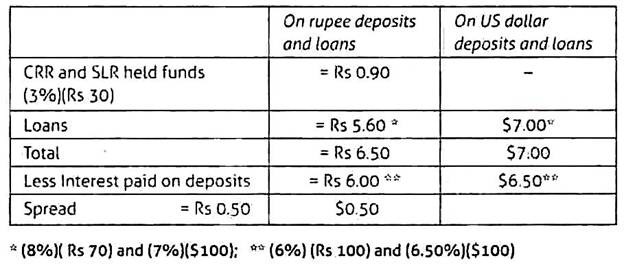

The Euro-bank can earn the same spread on its Eurocurrency deposits and loans, as it does on its domestic currency deposits and loans, in spite of charging a lower interest rate on Eurocurrency loans and paying a higher interest rate on Eurocurrency deposits. Suppose for every Rs. 100 of deposits, a bank earns 3% on its CRR- and SLR-held funds and 8% on its loans, while the bank pays 6% on deposits. The bank pays 6.50% on Eurodollar deposits and charges 7% on euro dollar loans.

Its spread is Rs. 0.50 and $0.50 as shown below:

The cumulative effect of these actions by borrowers and lenders caused a shift in financial intermediation from domestic financial institutions to external financial institutions. Instead of rupee deposits and rupee loans being made by a bank in India, if the rupee deposits are in a bank in Singapore, which then makes rupee-denominated loans, it implies a shift in intermediation from India to Singapore. When this happened to the US dollar, American banks began losing business to banks in Europe. European banks were prepared to earn lower spread on their Eurodollar business, as compared to the American banks.

There are no restrictions on the maximum interest rate payable or chargeable on Eurocurrency deposits and loans respectively. There are no regulations with respect to directed credit, or any ceiling on sector-wise credit. Eurocurrency deposits are not subject to deposit insurance. The Eurocurrency business of a bank does not fall within the regulatory purview of the central bank of the country in which the bank is located. The unrestricted nature of the Eurocurrency market has been credited for its rapid growth.

By the end of 1968, the euro dollar market alone had an estimated size of $25 billion (excluding inter-bank deposits), and was approximately equal in size to the total money supply in Italy, Japan and Britain. The market was extremely competitive as borrowers (corporations) switched between dollar loans and Eurodollar loans based on a comparison of interest rates. A majority of Eurocurrency loans have a floating rate of interest linked to one-month, three-month, or six-month LIBOR or EURIBOR.

The Bank for International Settlements (BIS) estimated the size of the Eurocurrency market in the 1960s on the basis of the external liabilities in foreign currencies of banks in eight European countries, namely Belgium, Luxembourg, France, Germany, Italy, Netherlands, Sweden and Britain. In the 1970s, the BIS began including data on the external liabilities in foreign currencies of Canadian, Japanese and American banks located in Japan, Singapore, Panama, Hong Kong, Bahamas and the Cayman Islands.

This is an indication of the explosive growth of the Eurocurrency market—$105 billion in 1972, $250 billion in 1975, $9.5 trillion in 1999 and $23 trillion in 2006. The bulk of Eurocurrency deposits and loans is transacted in banks located in international financial centres such as London. More than two-thirds of Eurocurrency consists of Eurodollars.

Essay # 5. Regulation of Eurocurrency Market:

The offshore activity of Euro-banks does not come under the regulatory purview of any central bank. Does that mean that offshore activities are totally unregulated, and no central bank is responsible? Not so. All banking activities (including the offshore activity of Euro-banks) are covered by the Basel Concordat (1974).

Under this agreement, the central banks of 31 countries agreed to be lender of last resort to their respective offshore banks. That is, the Federal Reserve would be the lender of last resort to the offshore activities of US banks; the Bank of England would be lender of last resort to the offshore activities of British banks and so on.

In 1980, the Bank for International Settlements (BIS) came out with a ruling that the commercial banks that had headquarters in the countries that were signatories to the agreement, had to prepare consolidated financial statements. This meant that the central bank of a country which was signatory to the BIS agreement, had a right to inspect the records of offshore banking activities of the commercial banks that came under its jurisdiction.

That is, the Bank of England could inspect the records of the offshore activities of a British bank, since the Bank of England regulated the latter. Thus, it is wrong to assume that Euro-banking is unregulated. But Euro-banking does not attract CRR and SLR, does not have deposit insurance, and does not need to meet directed credit stipulations that have to be adhered to by the domestic banking system.

Essay # 6. International Financial Centres of Eurocurrency Market:

A financial centre is ‘a city that has a high concentration of financial institutions and where the financial transactions of a country are centralised Mumbai is India’s financial centre. London, New York and Tokyo are the leading financial centres. Singapore and Hong Kong are replacing Switzerland as the global centres for private banking.

Switzerland is renowned for its banking secrecy. In 2007, the US Justice Department began an investigation of Union Bank of Switzerland (UBS), Switzerland’s largest private bank. The investigation ‘ stated that UBS and other Swiss banks made it possible for wealthy Americans to evade taxes in the USA. UBS settled out of court, and agreed to disclose the names of several US clients to the Internal Revenue Service (the US tax authorities).

Offshore Financial Centres:

Financial transactions can take place in any of the following combinations:

i. Domestic borrowers and domestic lenders (occur in the domestic financial market).

ii. Domestic borrowers and foreign lenders

iii. Foreign borrowers and domestic lenders

iv. Foreign borrowers and foreign lenders

When at least one of the parties is foreign, the transaction is said to take place in the international financial market. Financial transactions between foreign borrowers and foreign lenders are called Entrepot or offshore transactions. They occur in the offshore market. As the Eurocurrency market took off, the offshore market suddenly rose to prominence. It was no longer necessary to locate a bank’s branch in an important international financial centre such as London, New York or Tokyo. With the improvement in communication technology, it did not matter if the branch was located in a relatively small and unknown part of the world.

As a result, places such as the British Virgin Islands, Cayman Islands, Nassau, Bahamas, Bahrain, and Singapore soon emerged as international financial centres as rivals to London and New York. There are virtually no restrictions on the movement of Eurocurrency in and out of the offshore centre and banking secrecy is very high. These areas have very little governmental regulation/control of banking activity and offer the additional advantage of a favourable tax regime.

In 1929, Luxembourg exempted holding companies from taxation and therefore, with the growth of the Eurocurrency market, it emerged as an important international financial centre. From a mere 19 banks in 1964, it had 156 banks in 2008. Forty-six of these were branches of foreign banks. Luxembourg is Europe’s largest private banking centre and one of the world’s richest countries. More than one-fifth of its GDP is generated by the financial sector, comprising offshore and international banks (most of which are universal banks), hedge funds, and more than 250 re-insurance companies.

Similarly, in 1968 Singapore decided to encourage the channelling of US dollars into Singapore and lend them to borrowers in neighbouring Asian countries. The Monetary Authority of Singapore (MAS) gave a number of concessions to foreign banks to make them set up branches in the country. A lower rate of tax was levied on interest from offshore loans earned by the branch of a foreign bank located in Singapore and the requirement of 20% liquidity ratio was waived for all financial institutions authorized to deal in foreign exchange.

The Monetary Authority was aided by a strong government that ensured economic stability. The MAS divides commercial banks into three categories—full banks (which are universal banks), wholesale banks (which cannot conduct Singapore dollar-denominated retail activities), and offshore banks. Among the full banks, the MAS permits some banks greater freedom—seven of the 23 ‘full bank’ foreign banks located in Singapore, have ‘Qualifying Full Bank’ status. This enables them to operate from 25 locations in Singapore. Such flexibility, and the acceptance of the Eurocurrency market and international banks as drivers of economic activity, enabled Singapore to become a major international financial centre.

Hong Kong, on the other hand, embodied the free market spirit. It had no central bank (therefore no banking regulation), and minimum interference from the government. In 1973, exchange controls were removed. Along with a strong economy, this gave the necessary impetus for Hong Kong to transform itself as an international financial hub. In the Channel Islands, Nassau, Cayman Islands, and Panama, the extremely lenient tax laws, lack of exchange control restrictions, and minimal banking regulation were the reasons for banks clamoring to set up branches in these countries.

The two-day Economic Conference held in November 2006 noted that tax havens are used by investors to route their investments to India. Tax havens have come under increasing scrutiny of financial authorities, and several have reluctantly agreed to cooperate with investigators tracking the flow of money across borders.