Here is an essay on the ‘Strategic Development of a Firm’ for class 11 and 12. Find paragraphs, long and short essays on the ‘Strategic Development of a Firm’ especially written for college and management students.

Essay Contents:

- Essay on the Principles of Business of a Firm

- Essay on Competitive Advantage of a Firm

- Essay on Strategic Intent of a Firm

- Essay on Core Competence of a Firm

- Essay on Strategy as Stretch and Leverage of a Firm

- Essay on Taking Charge of the Future of a Firm

- Essay on Dominant Logic and Paradigm of a Firm

- Essay on Competing through Collaboration of a Firm

- Essay on The 7-S Framework of a Firm

Essay # 1. Principles of Business of a Firm:

In his article “The Theory of Business”, Prof. Peter Drucker proposed that organisations-particularly those that have experienced success over several years in the past-need new assumptions or principles to rebuild themselves and survive the future competitive battles. The assumptions which shape a firm’s organisational and managerial behaviour, influence its decisions on what to do and what not to do, set targets that are considered meaningful, and evaluate and select alternatives from the many possible choices in such areas as the segments to be served, competitors to be targeted or technologies to be developed, are termed by Drucker as a company’s ‘theory of the business’. For long-term success, a firm needs the right theory of business, a theory which is clear, consistent and forward-looking.

The key characteristics of such a theory are:

(a) The reality must fit the assumptions made with regard to:

(i) environmental characteristics,

(ii) corporate mission, and core competencies;

(b) The assumptions in all of these three areas must be in balance with each other;

(c) The theory of business must be communicated widely across the organisation;

(d) It needs to be tested on a continuous basis.

It must be remembered that against the background of a fast changing environment, a theory of business, once developed, rarely lasts for a long time. As a matter of fact, every theory of business becomes obsolete and invalid after some time. Unfortunately, most organisations and their managers tend to discount any sign of obsolescence and may even develop a defensive attitude towards the whole matter.

Incremental changes may be made at the margins to show the world at large that the firm is conscious about the reorientation needed; but such actions normally do not produce the desired result if the theory itself has become obsolete. Rather, it is better to start thinking about a new theory and develop a fresh set of assumptions on environment, corporate mission and core competencies.

It is useful to examine the business theory of a firm every few years, and during such an introspection the managers must challenge their assumptions on product, market, competition, technology, distribution and organisation (including policies and procedures) and check if these are relevant to their future requirements.

A dispassionate analysis of past performance against the assumptions made in all these areas will throw fresh light on what went wrong and why the ‘right’ assumptions made a few years ago did not work. Early diagnosis, objectivity in collecting and analysing data, and finally, the commitment and the forward outlook of the leadership to effect a change-all carried out in a period of comparative calm rather than under a crisis-can facilitate the transition to the new theory of business.

Essay # 2. Competitive Advantage of a Firm:

Many firms have one or the other distinctive competencies in such areas as cost control, quality, customer service, new product launch, etc. However, these distinctive competencies need not necessarily lead to competitive advantages. To put it differently, the areas where a firm has competitive advantages are the areas of distinctive competencies, but all distinctive competencies are not sources of competitive advantages.

(a) A competitive advantage is characterised by the following.

(b) It favourably distinguishes a firm or its products from those of its competitors.

(c) It resides in the minds of the customers and not in the mind of the organisation.

(d) There can be multiple potential bases for competitive advantages, typically a combination of bases.

It changes over time due to:

(a) Actions of the firm,

(b) Actions of competitors, and

(c) Changes in customers’ needs.

It must be remembered that a competitive advantage lasts as long as the competitors allow! This being so, the strategy of a firm is and should be ultimately concerned with the development and maintenance of competitive advantage(s).

A firm can have competitive advantages along one or more of the following dimensions:

(a) Cost (across the value chain),

(b) Quality (across the value chain) Customer service,

(c) Speed,

(d) Variety,

(e) New product introduction,

(f) Skills,

(g) Brand,

(h) Distribution network,

(i) Business systems and processes that add value to customers network of relationships that exists among suppliers, distributors and customers as well as with employees, and

(j) Reputation and responsiveness.

Even though a competitive advantage is extremely difficult to develop and very easy to lose, it can be sustained if the following conditions are satisfied:

i. Customers perceive as well as experience a consistent difference in the important attributes and functionalities (in product and service areas) between the firm and its competitors.

ii. The difference is due to a gap in competencies of the firm and its competitors.

iii. The difference in attributes and competencies is expected to be lasting.

The essence of competitive advantage is to ensure the highest possible value addition to the customers at the lowest delivered cost. To achieve this, the various departments and functions of the firm should not only excel vis-a-vis the competitors in their respective areas of responsibilities, but they should also collaborate and coordinate their activities in a manner that could help in creating and upgrading the organisation’s competitive advantages on an ongoing basis.

Essay # 3. Strategic Intent of a Firm:

The companies that have achieved global leadership over the past three decades invariably began with an ambition that was out of line with their resources and capabilities. But this created a desire to win and they sustained the same over a long period of time. This desire is termed by Hamel and Prahalad as ‘Strategic Intent’. Strategic intent is really an energising dream that can provide the emotional and intellectual energies to drive towards the future.

It specifies the desired leadership position of the organisation and indicates the nature and range of competencies that have to be developed or sustained to achieve the same. Pursuing such a strategic intent implies a significant leap beyond the current capabilities and resource base since the latter are insufficient for the task of achieving future leadership. It requires an organisation to be actively concerned in making the most of its limited resources.

Strategic intent is more than just a dramatic ambition.

The concept also helps in achieving the following, according to Hamel and Prahalad:

1. Drawing the organisation’s attention to the essence of winning; encouraging employees to perform better by communicating the value of stretched targets;

2. Providing scope for individual and team contributions;

3. Using the concept of strategic intent to guide resource allocation decisions within the organisation.

To achieve the strategic intent, the top management will need to:

(a) Create a sense of urgency;

(b) Inculcate a competitive spirit at every level through an extensive use of competitive intelligence;

(c) Train employees to develop the skills they need to work effectively;

(d) Give the organisation time to execute one challenge before launching another;

(e) Set clear milestones and install review mechanisms.

For the effective implementation of strategic intent, both senior management and lower level employees must accept a reciprocal responsibility for competitiveness. Reciprocal responsibility-ac- cording to Hamel and Prahalad-is critical because future competitiveness will depend ultimately on the pace at which a company acquires new advantages deep within the organisation.

Hamel and Prahalad have suggested the following approaches to achieve strategic intent:

(a) Create layers of advantages;

(b) Search for weaknesses in the competitors’ strategies and build positions in undefended territories;

(c) Change the terms for business transactions;

(d) Compete through collaboration and strategic alliances.

Strategic intent, if developed appropriately, encourages managers to commit themselves to ambitious targets. It also helps in developing faith in an organisation’s ability to achieve such ambitious goals. Once such a challenge has been taken, senior managers gain confidence to commit themselves and their companies to industry leadership.

Essay # 4. Core Competence of a Firm:

The concept of core competence was developed by Prahalad and Hamel. According to them, a company’s competitiveness in the short run is derived from price/performance attributes of its current products. But as a fallout of global competition, all competitors are converging on similar and formidable standards for cost and quality and the same have become less and less important as sources of differential advantage.

In view of this development, competitiveness in the long run can be derived from an ability termed as “core competence”, to build at a lower cost and more speedily than the competitors. Core competence is defined by Prahalad and Hamel as collective learning in an organisation, especially on how to co-ordinate diverse production skills and integrate multiple streams of technologies. To facilitate co-ordination and harmonisation, there must be communication, involvement, and a deep commitment to working across organisational boundaries.

Core competencies do not diminish with use. Rather they are enhanced through application and sharing. The underlying core competencies bind existing businesses and also act as drivers for new business development.

According to Prahalad and Hamel, successful companies do not describe themselves as consisting of different businesses. Rather they define their business as a portfolio of competencies. These successful companies are aware that building core competencies does not mean outspending rivals on R&D, nor does it mean any sharing of costs or a common component across SBUs. It is also different from integrating vertically.

Core competencies are normally characterised by the following:

(a) It enables access to a wide variety of markets, both existing and potential.

(b) It enhances the perceived consumer benefits of the end products.

(c) It makes it difficult for the competitors to imitate, and thus, act as an entry barrier.

(d) It cannot be traded or purchased, and its learning cannot be speeded up in the short run just by making an investment.

Companies that judge the competitiveness of their firms as well as that of their competitors primarily in terms of price/performance of end products tend to lose sight of the importance of core competence, and, as a result, make hardly any effort to build or enhance the same. The skills that help in developing future products cannot be learnt by outsourcing or entering into an original equipment manufacturer (OEM) supply relationship.

Even where it has been decided to outsource product or technology development, companies must first take into account whether they want to build competence in-house and use the alliance being entered into for learning new competencies at a rapid rate. Setting clear goals for competence building help in facilitating this learning process.

Prahalad and Hamel introduced the concept of core products while discussing core competencies and stated that the latter are linked to the end use items through such core products. These core products are designed and developed through a combination of one or more core competencies. Seen from this angle, core products are components or subassemblies that actually add value to the end use items.

Since core products are different from end use items, it is necessary to distinguish between the brand share the company achieves in the end product application and the manufacturing share it achieves in any particular core product. Prahalad and Hamel suggested that this distinction should be made between core competencies, core products and end products since global competition is different at each level.

To build or defend leadership in the long run, a company should aim to be a winner at each of these three levels. In general, to continue as leader in their chosen core competence areas, companies should maximise their world manufacturing share in core products. This would be desirable strategically not just because of the revenue potential and access to market feedback, but also in order to take away investment initiatives from existing and potential competitors. Another benefit of a dominant position in core products is that it would allow a company to share the evolution of applications in the end product markets.

Companies that try short-cuts to build a market share by relying on the competencies of external organisations rather than investing in the in-house development of core competencies and world core product leadership, may be taking too much of a risk. Keeping this in view, it is preferable for companies to have a core competence agenda. What is needed is to build a ‘strategic architecture’ that can establish objectives for competence building. A strategic architecture is nothing but a ‘Road Map’ for the future that identifies core competencies to build and their constituent technologies.

To develop such a strategic architecture, a company must answer some fundamental questions:

(a) How long will it be possible for us to preserve our competitiveness if we do not control the required core competence?

(b) How important is a particular core competence to produce the perceived consumer benefits?

(c) What future opportunity will not be available to us if we were to lose a particular competence?

The architecture according to Prahalad and Hamel, provides a logic for product and market development. It also helps in making the resource allocation processes transparent to the entire organisation. It ensures that lower level managers understand the logic of allocation priorities, and also disciplines the top management so that it maintains consistency in decision making. It creates an appropriate management culture that promotes collaborative working, encourages acceptance of change and a willingness to share resources, protects proprietary skills, and enables the organisation to think on a long-term basis.

For the proper development of core competence, the internal organisation and administrative systems will need to be designed and implemented properly. This shall help direct the attention of managers towards the need to develop and strengthen the core competencies, and also towards sharing resources, knowledge and people across the SBUs to achieve the said purposes.

During the 80s and 90s, many firms in the developed world divested their non-core activities, which they had entered in the late 70s and 80s in order to strengthen their competitive position and improve shareholder value. However, in the context of a developing country, managers confront some special problems, such as lack of world -class competencies that can enable domestic firms to compete globally and build a strong global position in order to sustain continuous growth.

At the same time, quite a few new opportunities may open up as a developing country makes rapid progress in new areas (such as the infrastructure sector) which may be exploited by cash rich and well managed local firms, even though these new areas may be outside their areas of competencies. Many of these new and unrelated areas of opportunity may not face global competition in the near future for a variety of reasons (such as the activity may be a local business, or the size of the opportunity may be such that no global firm would find the same attractive).

Academicians as well as practitioners differ on the relevance of the concept of core competence in the Indian context, particularly with regard to developing a future diversification strategy.

Two distinct perspectives can be observed from various publications that appeared in the Indian business press and other writings during the last few years’:

A. Pro-Core Competence:

(a) A company should diversify for leveraging the collective learning in the organisation, a significant part of which is core competence.

(b) Competitive strength is best ensured in terms of core competencies, and hence diversification should be limited to only those fields where existing competencies can be used.

(c) Diversification to new fields, having synergy with existing core competencies, helps in creating value for customers and also in gaining competitive advantages by way of reputation, brand extensions, new product development, etc.

(d) A company is unlikely to build world leadership in more than a few fundamental competencies and diversification to areas outside the same is not desirable.

B. Anti-Core Competence:

(a) The accumulated skills of an organisation may not mean anything today given the fast changing market scenario.

(b) Since the market decides success and failure, the focus must be on products and services that will be demanded by the customers and not on the underlying core competencies.

(c) The core competencies required to move into new business areas can be acquired by entering into strategic alliances or through an outright purchase of the know-how.

(d) A business group can have a highly diversified portfolio, and the core competencies underlying each portfolio can be very different from each other. This is needed to exploit the opportunities that may open up from time to time in unrelated areas.

(e) In many fields, investments in manufacturing may not even be necessary for leadership, and hence, core competence is not a critical issue to be considered.

There is a growing debate among academicians and practising managers regarding the relevance of the concept of core competence and its usefulness in determining the strategic posture of a firm. It seems that a certain level of polarisation has already taken place in this regard. This author believes that both the pro-core and anti-core schools of thought have their relevance and utility depending on the context in which the strategic options are being examined.

What is needed are specific research initiatives that will develop a framework describing the conditions under which a firm in a developing country may consider entry into non-core areas. The framework will also specify the kind of administrative structures (including legal structure) and systems that are needed to facilitate the effective implementation of the new strategy, including the rapid development of core competencies in the new field.

It is also pertinent to mention that for the successful exploitation of any new business opportunity, a firm needs to go beyond the core competencies in such areas as product development, process efficiency and application know-how. It must focus on developing total capabilities across its entire value chain so that it can create and deliver value to customers in a cost effective, unique and sustainable way. To develop such total capabilities, the firm needs to design a network of relationships with suppliers and customers as well as with its own employees.

This win help the firm acquire a reputation of being a reliable organisation in all aspects of its business, and build firm wide competencies for innovating across its value creating processes on an ongoing basis. Without such embedded total capabilities it is not be possible to build and sustain competitive advantage in the newly chosen field, even if there may be scope to exploit the existing core competencies.

Essay # 5. Strategy as Stretch and Leverage of a Firm:

The essence of the strategic initiatives undertaken by the firms that have had a continually good performance over the last 20 to 30 years is stretch and leverage. The concept of stretch is based on the principle that an organisation’s competitiveness is created by the gap between its resources and the goals of its managers.

Some of the benefits of stretch are:

(a) Rapid development of product

(b) Well-Coordinated cross-functional teams

(c) Thrust on a select number of core competencies

(d) Strategic alliances with suppliers so that the desired output can be produced with less resources

(e) Organisation wide programmes for employee involvement and consensus.

According to Hamel and Prahalad, companies that adopt the principle of stretch as the means to attaining industry leadership are characterised by the unreasonableness of their ambition and their creativity in getting the most out of the least. For these companies, creating a stretch between the resources and aspirations is the most important task of the senior management.

Successful companies pursue the policy of stretch since they are aware that having more resources does not necessarily ensure industry leadership. Rather, the ability to manage these resources through right deployment and leveraging is the key to gaining competitive advantage. The leveraging of what a company already has is a creative activity. To such companies leveraging resources is as important as allocating them.

There are five different routes to resource leveraging:

a. Concentrating’ resources on key strategic goals.

b. Accumulating’ resources to achieve higher efficiency.

c. Complementing’ one kind of resource with another to ensure higher value addition.

d. Conserving’ resources through the minimisation of waste.

e. Recovering’ resources from the marketplace in the shortest possible time.

Conceptualising strategy as stretch and leverage is essential for gaining industry leadership. A very different kind of managerial mindset is necessary to give impetus to this concept. Managers need to be encouraged to commit themselves to ambitious goals even if the resources available are apparently lower than necessary. And when such gaps are created between aspirations and resource availability, organisations tend to achieve competitiveness by pursuing the policy of stretch and leverage.

Essay # 6. Taking Charge of the Future of a Firm:

The quest for competitiveness, with a view to competing for the future, consists of three main categories of actions, viz:

(a) Restructuring the portfolio and downsizing the headcount

(b) Re-Engineering the business processes and effecting continuous improvement

(c) Reinventing industries and regeneration of strategies

While the first two actions can help an organisation become smaller and better, and thus help it protect today’s business, the third action, viz. the ability to reinvent industry boundaries and pursue breakthrough strategies, will ultimately determine which firm of an industry will reach the future first and also dominate the same.

The starting points for reinventing the industry will be to understand the following three aspects, viz:

(a) The three phases of competition that need to be responded to for intercepting and influencing the future:

(i) Competition for intellectual leadership to develop new products/market ideas;

(ii) Competition for conversion of such ideas into tangible, higher quality products/services with minimum resources and time; and

(iii) Competition for gaining market share once the products/services conceived and developed, as above are launched.

(b) Unarticulated and unserved needs of the customers, which are likely to be the sources of demand for future products/services, and hence, should be identified well in advance.

(c) The profile of future customers and competition, and changes that are likely to take place in products and services, distribution channels, sources of competitive advantages and margins and also firm’s core competencies and skills.

Unfortunately, managers of most firms do not have the answers to the three issues outlined above and as a result are not in a position to envision the future and then create the same. They tend to follow the familiar path by looking at past trends. However, firms that are desirous of dominating the future and obtaining a favourable share of the future market pursue the path of great opportunities.

They do not take the route of fast followers and adopters since they know that the path cannot ensure extraordinary growth. Rather, their emphasis is on creating new industries or changing the rules of existing industries with a view to occupying the number one position.

To achieve all these, they take two distinct steps:

i. Establish a ‘core competence agenda’ that clearly spells out how the existing competencies can be strengthened and leveraged to protect the current market positions as well as to exploit new opportunities both in existing and new markets.

ii. Create a ‘strategic architecture’ that indicates a point of view about what attributes or benefits will be provided to the customers over the next 5 to 10 years, and also what new competencies will be needed to create the same.

Strategic architecture, is nothing but a blueprint for developing new competencies as well as re-conceiving the existing ones, This spells out clearly what capabilities are to be built in the short and medium terms in order to drive successfully to the future, Needless to say, the future is now, and the long-term starts today and not 5 or 10 years later.

It is clear from the above that a firm needs a new strategy paradigm for creating and dominating emerging opportunities, the objective being to get a major share in the new competitive space, The new paradigm will require foresight in order to transform future industry through pursuing a path breaking strategy; there will be the need for stressing the critical requirement of stretch and leverage and taking all the actions necessary for getting to the future first, including shaping the future and building leadership in core competencies, The task involved is daunting but challenging and can be achieved by encouraging employees to pursue ambitious aspirations, and also by giving everybody an opportunity to make a major contribution so that the firm’s desire to control the future is realised.

Essay # 7. Dominant Logic and Paradigm of a Firm:

A dominant logic, as defined by Prahalad and Bettis, is “the way in which managers conceptualise the business and make critical resource allocation decisions-be it in technology, product development, distribution, advertising, or in human resource management. These tasks are performed by managing the infrastructure of administrative tools like choice of key individuals, process of planning, budgeting, control, career management and organisation structure.” For a particular business, there is normally one specific dominant logic, but for a firm that has a diversified portfolio and involves extensive strategic varieties (in such areas as competition, technology and customer-mix), there will be multiple dominant logics. Dominant logic, specific to each line of business, is a combination of both the knowledge and the processes by which such knowledge is applied.

The above implies that the ability of a company to manage a diversified firm is directly dependent on the dominant logic that the top management of the firm is used to. In most cases, the dominant logic of the top management of a diversified company tends to be influenced by the core activities in which the firm has been involved over a long period of time.

As a result, the characteristics of a core business and the experience thereof influence to a great extent the approaches that are followed to define problems and the decisions regarding diversified activities. This is so, as dominant logic is nothing but a mindset or a view about how a business should be managed by designing the structures, systems, processes, and the deployment of resources.

This mindset is greatly influenced by past experience in core businesses. Normally, it is difficult to change the dominant logic which has been formed over the years, or to add a new dominant logic to a company’s repertoire, even when in these days of fast-changing environment, it is necessary to change the dominant logic, specially if a firm wishes to sustain and improve its performance. This change in logic is possible only if the firm and its dominant coalition are able to learn at a rapid rate.

Dominant logic, as explained above, is really the paradigm of an organisation as conceptualized by Kuhn. The paradigm of any organisation consists of three layers, viz. values, beliefs and assumptions. Of these three, assumptions are key since these are ‘taken for granted’ and employees find it difficult to identify and explain them. Such ‘taken for granted’ assumptions do not surface unless challenged consciously and relentlessly. Failure to do so is likely to override all logical and explicit analyses pertaining to various strategic tasks.

The paradigm, thus defined, gets encapsulated in a ‘cultural web’ that consists of stories, symbols, rituals and routines a power structure, control system and organisation structure. It influences the way the external environment is analysed and internal strengths and weaknesses are assessed.

As a result, a firm’s understanding of its own strengths and weaknesses and of the opportunities and threats tends to be more internally constructed rather than objectively assessed. A direct fallout of this is that the choice made about the strategies to be pursued or the administrative systems to be implemented may not turn out to be the most optimum.

The paradigm also prevents an organisation from recognising the need to reposition itself in the face of the changes taking place, leading to a ‘Strategic Drift’. Such strategic drifts-defined in terms of the gap between the extent of change needed and the extent of change actually effected-take place when the paradigm as well as the constraints of the cultural web reduce the firm’s ability to initiate unconventional and innovative moves.

To come out of these clutches, the members of the firm will need to question and change substantially the three components of the paradigm (viz., values, beliefs and assumptions). This, as evidence suggests, does not occur easily and as a result managers tend to adopt familiar strategies and responses, and the path conditioned by the existing paradigm. Organisations, attempting to improve the quality of their strategy processes, need to appreciate such adverse influences of their own culture.

Essay # 8. Competing through Collaboration of a Firm:

With the rising intensity of competition and the ever-changing requirements of customers, the future will belong to those firms that will be able to cooperate with their customers as well as competitors. Cooperation with customers will include providing active inputs (information, know- how and physical inputs) to them and also co-managing their facilities, wherever possible.

The objective of such cooperation will be to make customers’ businesses more competitive which will in turn make the firm’s business competitive. A particular area of emphasis is the co-management of customers’ processes enabling the latter to achieve a higher value addition and cost-effectiveness than what they would have achieved had they managed on their own.

Cooperation with competitors will be necessary to enter into strategic alliances and joint ventures In the days to come, in most of the fast-changing, high-growth industries, the competition is going to be between alliances and not between one firm and another. A particular firm may have multiple alliances for this purpose. Competition through collaboration will also include the efforts made by the competing firms to network with their various suppliers to improve their own products and processes, add more value, and reduce input costs. There will be a need for two-way communication to facilitate collective learning.

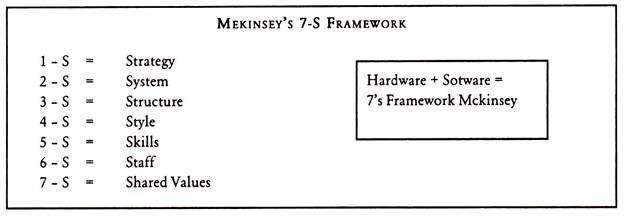

Essay # 9. The 7-S Framework of a Firm:

The 7-S framework, developed by McKinsey Inc. of the USA, is a very useful model that provides a comprehensive view on organising a firm. According to this framework, it is not sufficient to concentrate on 2-S alone, viz. strategy and structure (called ‘hardware’) to understand and manage the processes of strategy formulation and implementation effectively; there is a need to pay similar attention to ‘software’, such as style, systems, staff, skills and shared values (i.e. 5-S).

These seven variables interact with each other and influence the overall outcome. In case any change is needed in one or more of the seven variables as response, to the shifts or turbulences in the environment, the remaining variables will need to be reviewed afresh to check their relevance and suitability vis-a-vis the changes proposed in the select variable(s).

Successful and innovative companies are especially good at reviewing the combination of these seven variables on an ongoing basis in order to respond continually to changes and to maintain their excellence. The emphasis on ‘soft’ issues, such as style, systems, staff, skills and shared values facilitates the development of the right strategy as well as its implementation.

Putting it conversely, the organisations that fail to take a comprehensive look at all of these seven variables run the risk of sub-optimisation and falling out of line with the needs of the time. The framework brings out the fact clearly that any piecemeal and static approach in dealing with strategy, structure, systems, etc., separately is not conducive towards continuing growth and sustainable excellence.

The 7-S model has important implications for strategy implementation.