Operations management is the process of managing the production of goods and services. Thus operations is a broad term that encompasses both hard-goods manufacturing management and service management.

Traditionally, the term ‘production’ brings to mind smokestacks, assembly lines and machine shops. However, the functional field of production and operations management (P/OM) refers to the broader idea of the producing activities of all kinds of organisations — manufacturing or service, public or private, large or small, profit or non-profit.

Operations management refers to the set of managerial activities that organisations engage in to create their products and services.

These activities were earlier called “production management”. In those days, “production” seemed to focus too narrowly on manufacturing. When managers began to expand their view of production to include services and other intangible products, the term “production and operations management” evolved. So “operations management” is rapidly becoming the generally accepted phrase.

Operations and Conversion Processes:

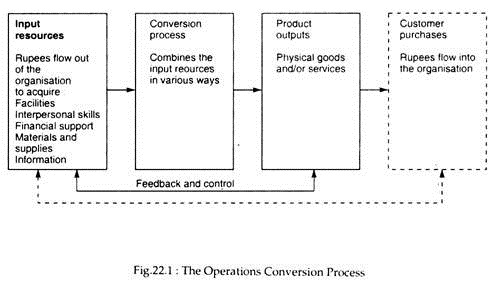

Operations, as a conversion process, can be visualised as consisting of the elements shown as solid lines in Fig. 22.1. Let us examine the inputs, conversion processes, outputs and feedback and control cycle depicted in the figure from an operations perspective.

Product Outputs:

The primary driving force of operations management is the desired end- product(s). Operations managers and operative employees must have a clear and precise definition of the product(s), including the key product attributes, the important quality characteristics, and quality standards for each attribute.

They also need to know how many of each product are needed and at what times to meet customer demand. In other words, operations employees need a clear picture of what they are trying to accomplish in their day-to-day activities.

Conversion Process:

Conversion processes may involve any of several different types of technologies, and technologies vary widely. Petroleum processing in a refinery operation utilises a continuous-process technology; automobile manufacturers employ primarily a mass-production technology; an aircraft manufacturer uses unit or small-batch technology.

Inputs:

Operations relies on receiving resources from other parts of the organisation and from the external environment of business. Operations cannot occur for very long without continuous supply of inputs. Some of these resources are more or less permanent, such as buildings and land devoted to production, whereas others are transient resources that are consumed fully on a day-to-day basis, such as raw materials and office supplies.

Feedback and Control:

Operations management systems are directed toward achieving goals. Once operations goals are established, controls help the system conform to standards of efficiency and effectiveness. Managers obtain information for evaluating system performance by monitoring various stages of the conversion process, the inputs and the product outputs.

The control system must provide timely information so that appropriate actions can be taken. Deviations from control standards are a prime basis for changing the inputs, the conversion process, or even the product or service design.

Operations as a Management Challenge:

The problems they face revolve around the acquisition and utilisation of resources for conversion. Some familiar operations activities and roles include purchasing, production forecasting, work flow and process analysis, job design, inventory control, production scheduling, quality control supervision, and manufacturing management.

These activities and roles seek to achieve balance and consistency among the three elements: inputs, the conversion process and outputs. These elements, in turn, must be in balance with and consistent with the other functions of the overall organisation. Therefore, each organisation has different expectations of its operations function, and the operations function in one organisation has different capabilities from that in another.

A set of product output specification that cannot be achieved in one conversion process may perhaps be easily met in another. The capability of the process, then, must match the output goals. A mismatch requires managers to decide whether to change the goals, product or conversion process. Similarly, input resources must be consistent with and supportive of the conversion process and its product output goals.

The proper outputs flowing from the conversion process indicate that the operations function is effective. Such success is usually not an accident, or at least sustained success is not. To maintain successful operations the production system must extend well beyond the operations activities.

In Fig. 22.1, for example, the dashed lines show the completion of the monetary resource cycle, emphasising that consumed outputs create the monetary resources that sustain operations and all other activities of the organisation.

In other words, products must be sold. Because the available monetary resources are limited, managers try to allocate them in a rational manner among all the organisation’s activities, including the operations function, by developing plans.