Here is a compilation of essays on ‘Wage Differentials in India’ for class 11 and 12. Find paragraphs, long and short essays on ‘Wage Differentials in India’ especially written for school and college students.

Essay on Wage Differentials in India

Essay Contents:

- Definition of Wage Differentials

- Degree of Wage Differential

- Wage Differential Based on Occupation

- Wage Differentials Based on Region

- Wage Differentials and Labour Market

- Factors Affecting Inter-Industry Wage Differentials

Essay # 1. Definition of Wage Differentials:

Wage differential allocates labour among different occupations, industries and regions in a manner so as to maximise national output. Wage differential is one of the important features of wage structure, wage and salary administration. It serves both economic and social functions. Wage differential also serves a useful social function by determining the social status of workers.

In analysing wage differentials, the following aspects are generally taken into account:

(1) Degree of wage differential:

(Wage differentials between the lowest and the highest paid employees in different organisations)

(2) Occupations/Skill wage differential:

(Wage differentials on the basis of occupation/skill)

(3) Regional wage differential:

(Wage differentials based on region)

Essay # 2. Degree of Wage Differential:

The degree of wage differential has been measured by taking the earnings of lowest and highest paid employees.

Wage differential has been calculated on the basis of:

(i) Basic pay

(ii) Basic pay and D.A. and

(iii) Total earnings.

On comparison of the degree of wage differentials in different undertakings in India, it appears that the wage differential in Rourkela Steel Plant is little higher than the all India average of 1: 9. But it is much higher than what the trade unions advocate.

The INTUC wants that the difference (based on basic pay) between the lowest and highest paid employees in Iron & Steel Industry should not exceed 1:8, while AITUC wants it 1 : 4. But the actual difference (on the basis of basic pay) is 1: 12.

The degree of wage differential in private sector undertakings is less than 1: 68. Risks and uncertainties being greater and managerial talent of the requisite calibre being still relatively scarce, the differential can be higher in the public sector.

The problem of degree of wage differentials in private sector undertakings was also examined by the Boothalingam Committee which has suggested that under existing circumstances a ceiling be fixed on the total earning of the highest paid employees.

Essay # 3. Wage Differential Based on Occupation:

Of the various types of differences that exist in wage structure the difference on the basis of skill is most common. An unskilled worker gets less pay than a semiskilled or skilled worker.

The skill differential serves three basic functions:

(i) It induces the worker to undertake more demanding or risky jobs.

(ii) It provided incentive to incur the cost of training and education, and encourages workers to develop skill in anticipation of higher earnings in future, and

(iii) It performs a social function by determining the social status of workers.

Wage differential on the basis of skill can be studied in two ways:

(a) Differentials based on occupation.

(b) Differentials based on skill.

The Fair Wage Committee was of the view that the differentials should be based on occupation and had suggested the adoption of a standard occupational nomenclature so that the work of classification and assessment may be undertaken on a uniform basis throughout the country.

Same wage boards, for example, wage boards for Sugar, Iron & Steel, Cement and Cotton textiles tried to standardize occupational nomenclatures, but failed. This is why the wage boards, instead of adopting a standard common occupational nomenclature, have divided the various occupations in different grades depending on the degree of skill involved.

In analysing wage differentials based on occupation, various difficulties may be faced, like standardisation of occupations, absence of job description and job specifications etc.; owing to which it is generally decided to take a few common occupations which may be considered as standard.

Essay # 4. Wage Differentials Based on Region:

Wage differentials have been examined also on the basis of regions. Regional wage differential refers to differences of workers earnings doing the same job in different units of an industry located in different regions. It is used also to denote the difference in average wages of all workers employed in an industry in different regions.

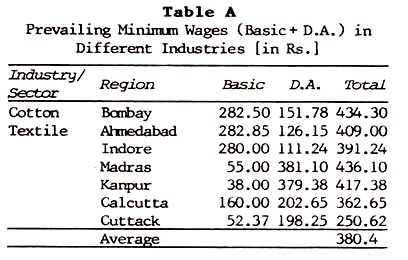

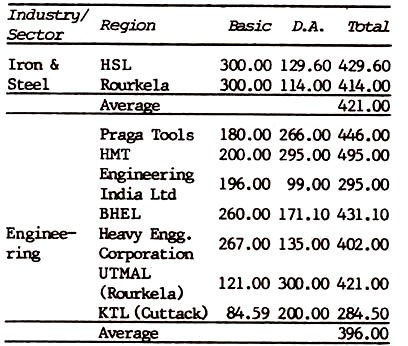

It appears from Table A that among the textile workers, workers of Madras are highest paid while that of Cuttack are the lowest paid. The wage differential between a textile worker of Madras and Cuttack is almost 74 per cent.

Similarly, in engineering industries, the wage differential of workers of HMT and KTL is almost 74 per cent. Various factors are responsible for these regional wage differentials like cost of living index, ability of the enterprise to pay, personnel policy and a public wage which the organisation wants to create.

Some degree of wage differential based on the size of the unit, degree of sophistications in technology or other factors is desirable to achieve certain economic and social objectives. Wage differentials become a source of irritation if anomalies and disparities exist in degree of wage differentials.

Unfortunately, no serious thinking has been given in India for evolving a proper wage structure including a national basis of wage differentials. The wage boards on which this responsibility devolved did not make any serious effort owing to one reason or another.

The Boothalingam Committee too could not perform this task. But this matter cannot be postponed further as it has become a big source of conflict between labour and management.

Sometimes these conflicts may put the entire nation to ransom. At the same time, evolving a national wage structure having a rational basis of wage differential is not an easy task. Management, government or workers and their representatives alone cannot perform this task.

Management or government as employer could evolve a wage structure including a rational base of wage differential. But that may not bring the desired result, unless accepted by workers and their representatives.

Hence co-operation and mutual understanding between labour and management and also government is one of the pre-requisites for implementation of a scientific wage structure including wage differential.

Determination of wage differentials in a manner that does not disturb the differential which has come to be regarded as fair and traditional, is the second important pre-requisite. If the system disturbs the pattern or degree of differential which has been accepted by workers as fair and traditional, it may fail.

Essay # 5. Wage Differentials and Labour Market:

The equalizing forces act in labour market, although less quickly and easily than in the other markets. In a given technological set up, however, while some movements are possible and easy others are not so, at least in the short-run.

The equalizing tendency would, therefore, be found among the jobs between which movements are possible and not among the jobs between which movements are not possible. Therefore, the analysis of the labour market should make this distinction, arid then try to evaluate its competitive efficacy in equalizing the wage-rates in the technologically limited areas.

The various types of differentials, inter-industry, inter-firm, inter-occupation and inter-area have varying implications for labour market analysis. Modern technology makes inter- occupation movement highly difficult, and therefore, the wage-differentials among occupations, at least in the short-run, do not reveal anything about the degree of competitiveness in the market.

In the long-run, however, if competition is effective, people may be expected to be more attracted towards, and therefore, get themselves or their children trained in, higher wage occupations, thus bringing down the extent of occupational differentials.

Inter-industry differentials again do not reveal much on account of significantly different skill-mix required in the workforce of different industries under modern technological conditions. In the long-run, however, competitive forces that bring about a narrowing tendency in occupational differentials may also effect a narrowing tendency in inter-industry differentials.

Geographical differentials and inter-firm differentials, more particularly in the same occupation and industry, are thus the reliable indexes of the working of competition in the labour market. In a competitive national labour market with a high degree of inter-regional movements of labour in response to better earnings opportunity, the inter-regional differentials in wage will tend to disappear.

Assuming that all regions are homogeneous in terms of the level and structure of their economic activity, (or of industrial sector, if we are concerned, as we are here, with wage differentials in industries), and further assuming that costs of movements are negligible in the sense that their value spread over time is not significant enough to check the movements, the existence of geographical differentials would point to

imperfection in the working of the labour market mechanism.

Dropping the first assumption but retaining the second one, the mere existence of geographical differentials would not indicate the lack of competitiveness across the regions in the labour market. Here one has to go into the factors that cause these differentials.

In the competitive mechanism non-industrial, ‘region-specific’ characteristics do not feature as the major determining variables: the variables which explain the differentials have to be ‘industry’ characteristics such as product mix, productivity and technology.

In real situations, however, the ‘regional’ and ‘industry’ characteristics get many a time, fused together in such a way that even if there is a high degree of competitive mechanism working in the national labour market, the regional differentials may prevail because of the peculiar industrial characteristics of regions.

For example, the industry-mix differs from region to region, and the high wage areas may also be the areas’ with high wage industries and occupations. Therefore, it is not the observed geographical differentials as such, but their comparison with other types of differentials and explanation in terms of certain factors, that may provide the tests of the competitiveness of the labour market.

A Case Study:

A positive relationship between a State’s share in an industry and its relative wage rate may not in itself suggest the existence of industrial markets across the regions, but if it happens to be consistently stronger than the relationship between an industry’s relative share in State’s industrial structure and its relative position in the State’s wage structure, it may suggest a greater industrial than regional impact on the wage structure.

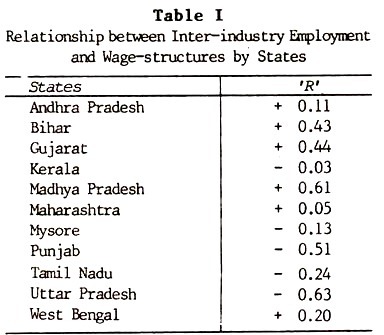

We find that the latter relationships are, on the whole, weaker in case of the 12 selected States among 15 selected industries than the industry-wise spatial relationship in India (Table I). In most of the States, the industry wage rates are not related to the industrial structure in any significant manner.

Note: Assam, Orissa and Rajasthan were left out because they did not have a sufficient number of 15 industries covered for this analysis.

The only States where we find strong positive relationships are Uttar Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh, Gujarat and Bihar. Incidentally, the industrial structure of these States is marked by a heavy predominance of one or two of those industries in which the relative position of each State is strongly positively associated with the relative wage rates among the States, namely Iron and Steel, Cotton Textiles and Sugar.

This suggests that there are some industries which have strong leading characteristics; they assert their importance within as well as across the regions, particularly when the dispersal happens to be highly unequal.

At this stage, one may find it worthwhile to try to separate the ‘industry’ and region effects on the relative average wage levels of different States, as the above analysis, in spite of its overall suggestion in favour of a greater effectiveness of ‘industry’ variable, seems to suggest a strong blend of the two types of factor.

Supposing that no regional differentials exist in individual industries, the observed differences in average wage among States may be ascribed to the differences in industry-mix. Calculating on this assumption, and giving due weights of man-hours worked in each industry, it may be mentioned that 34 selected industries, while constituting a major percentage, do not actually exhaust the total man-hours worked in a State.

For ‘other industries’, therefore, the total man-hours worked have been multiplied by the all-India all-industry average wage rate to calculate their wage bill. This is a major limitation of this exercise.

In a State, we get the ‘expected’ average wage rates which may be converted into wage relative with all- India all-industry average wage rate as 1, and their comparison with the actual wage relative with all-India all-industry wage rate as 1. This gives us the idea of the extent to which the deviation from all-India figures is attributable to industry-mix.

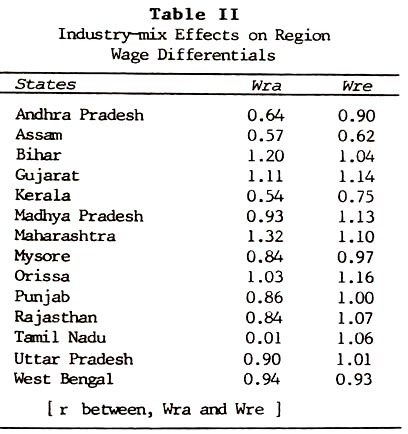

The calculations made on the above basis (Table II) reveal that in 6 out of 15 States, the expected deviation from all-India figures, after taking care of industry-mix, is very near the actual deviation. This means that virtually the entire deviation is explained by industry- mix.

These States are West Bengal, Gujarat, Orissa, Tamil Nadu and Assam. West Bengal pays 6 per cent lower than national average, while correction for industry-mix allows a 7 per cent lower than average level.

The actual average wage rate for Gujarat is 11 per cent higher than all-India, while on the basis of its industrial-mix, it should have paid about 14 per cent higher than national average. Orissa pays 3 per cent higher than the average while its expected level on the basis of industry-mix is 6 per cent higher.

Tamil Nadu pays 1 per cent above the national average while industry-mix allows a 6 per cent higher figure. And Assam’s actual deviation of 43 per cent is explained by industry-mix to the extent of 38 per cent. In these cases the divergences between the expected and actual deviation is marginal 5 per cent or less.

There is another set of six States where the expected deviation according to industry-mix varies from the actual deviation by an extent ranging between 11 to 20 per cent. These States are Uttar Pradesh, Punjab, Mysore, Bihar, Kerala and Madhya Pradesh in the increasing order of the deviations between expected and actual wage relatives.

The remaining three States Andhra Pradesh, Rajas than and Maharashtra show a difference of 26, 23 and 22 points respectively, between the actual percentage deviation and expected percentage deviation from all-India. Andhra Pradesh paid 36 per cent lower than Indian average against a 10 per cent lower expected on the basis of its industry-mix.

Rajas than is expected to pay, on the basis of its industry-mix, a wage rate 7 per cent higher than the national average while it actually pays 16 per cent lower than the national level. Maharashtra paid 32 per cent higher against its expected 10 per cent higher than all-India.

One may conclude on this basis that the first 6 States do not have a regional bias in their labour market, the next 6 States have only a slight regional bias, but the last three seem to have a significant impact of regional variables in their relative wage position.

On the whole, assuming a simple linear dependence of wage variations on industry-mix, around 63 per cent of the differentials would be explained in terms of industry-mix as indicated by the values of the coefficient of correlation between the actual and expected wage relatives of States (+ 734).

Essay # 6. Factors Affecting Inter-Industry Wage Differentials:

(i) Change in labour productivity,

(ii) Role of unions,

(iii) Rate of expansion,

(iv) Past rate of profitability,

(v) Change in the cost of living, and

(vi) Role of wage-fixing authorities.

The logic underlying the first two factors is the same as in the case of inter-industry wage differential at a point of time and is re-informed here in the explanation of changes in wages over time.

Rate of expansion becomes another important factor explaining wage changes in different industries since the industries which experience relatively larger expansion would normally have a comparatively higher demand for labour skills and consequently the rate of increase in wages in such industries is likely to be faster compared to others where the rate of expansion is smaller.

Past profitability is also likely to exert an influence on the wage change in different industries because the industries which enjoyed higher profitability in past would have better capacity to increase wages since, in their case, a higher increase in wages does not mean smaller profits compared to others.

Cost of living and role of wage fixing authorities are also expected to play an important role in wage changes, but in view of the non-availability of separate cost of living index of workers for different industries and because of problems of quantification of role of wage fixing authorities, factor analysis presented below is restricted to the first four factors.

The alternative formulation in which wage change occurs indifferent industries is explained in terms of change in labour productivity, degree in general and the increase in wages which is comparatively higher in industries and which recorded relatively a greater rise in labour productivity.

For example, industries such as aluminum, copper & brass, chemicals, soap, paints & varnishes, biscuit making and general & electrical engineering showed a comparatively larger increase in labour productivity and correspondingly, it is noticed, that these also witnessed a relatively higher increase in wage rates.

Similarly, at the bottom, there are industries which showed a relatively smaller increase in productivity. In fact, correlating changes in wages and changes in labour productivity, we obtained positive as well as highly significant values.

Degree of unionism also, on the whole, shows a positive association with wage increase in different industries. It is evident that barring sugar which is one major exception, industries such as sewing machines, aluminum, copper & brass, bicycles, cement and chemicals which record a high wage increase.

Among the industries which witnessed a comparatively low wage increase, rice milling, distilleries & breweries, wheat flour, oilseed crushing, fruits & vegetable processing, and jute textiles are main with relatively low degree of unionism.

Besides sugar, there are, however, few more notable exceptions like general & electrical engineering, soap, and paints & varnishes- where the wage increase is, no doubt, relatively larger but the degree of unionism is not equally high.

Rate of expansion also in general; show a close bearing on the wage increase in different industries. The industries such as general & electrical engineering, electric fans, sewing machines, electric lamps, chemicals, paper & paper board, glass & glassware and biscuit making show an expansion rate higher than average.

Iron & steel and ceramics are two major exceptions which although experienced a comparatively rapid expansion, but showed a relatively lower increase in wage rates.

At the lower end, the expansion was relatively low in distilleries & breweries, jute textile, oilseed crushing, wheat, flour, rice milling, and fruits & vegetable processing. Correspondingly, the increase in wages in these industries also found to be lower.

Rate of past profitability is obtained by expressing the gross returns (i.e. gross value added minus total wage cost) as percentage of total value of output. It includes, other than pure profits, the managing agents remuneration, take off pay etc. for which adjustment could not be made for want of break-up by these items in the published data.

Rate of profitability or profitability of returns could also be obtained by expressing the gross returns as percentage of capital employed. Since the available figures on fixed capital, as such, are based on historical prices, the use of first measure is made.

Along the industries enjoying a relatively high rate of profits in the past, chemicals, cement, sewing machines, paper & paper board, paints & varnishes, electric lamps, soap, electric fans, biscuit making and matches have come out with the expected pattern.

While, on the other hand fruits & vegetable processing, distilleries & breweries, plywood & pulp, iron & steel, sugar and ceramics display a dissimilar trend where, although the past rate of profitability is higher but the wage increase is relatively much smaller.

Similarly at the bottom, industries such as wheat, flour, rice milling, oilseed crushing, edible hydrogenated oils, woolen and jute textiles show the positive relationship, while cotton textiles, glass & glassware and tanning do not seem to support it.

Conclusions:

The inter-industry wage differentials in India and factors determining them bring out the following conclusions:

(a) There are significant variations in average daily wages across the industries. The industries which enjoy a comparatively high wage level are mostly of the nature of modern and capital goods and those witnessing a low wage are, in general, traditional and consumer goods industries.

(b) Coefficient of variation in wage rates has increased over the decade 1953—1963 indicating thereby the relative dispersion in wages of workers in different industries have widened over the period.

(c) The relative shift in the position of different industries in terms of paying wages during 1953-1963 was in favour of mainly those which already enjoyed a higher wage in 1953 and the industries which suffered relative losses are, in general, traditional and consumer goods.

(d) In the explanation of inter-industry-wage differentials as a point of time, variations in wage rates across the industries were explained in terms of labour productivity, importance of labour, skill composition of work-force, size of plant and degree of unionism. Nearly 75 to 83 per cent of the variations are explained by factors under consideration.

Labour productivity and importance of labour appear to be relatively more important in explaining inter industry wage differentials. Other factors, namely skill composition, size of plant and degree of unionism also found to be closely related with the wage rates across the industries.

(e) Between 1977-87 significant variations in wage change among the industries were observed. Variations in the rate of wage change are explained by changes in labour productivity, role of unions, rate of expansion and rate of past profitability. These factors taken together explained about two-third of the total variance.

Changes in labour productivity and rate of expansion seem to play an important role in the wage change in different industries; degree of unionism also exerts considerable influence, whereas the impact of past profitability, although the evidence is not conclusive, does not appear to be significant.