Here is a compilation of essays on ‘Wage Structure for Workers in India’ for class 11 and 12. Find paragraphs, long and short essays on ‘Wage Structure for Workers in India’ especially written for school and college students.

Wage Structure of Workers in India

Essay Contents:

- Essay on the Definition of Wage Structure

- Essay on the Factors Affecting Wage Structure

- Essay on the Theories of Wage Structure

- Essay on the Reformation of Wage Structure

- Essay on the Distortion in Wage Structure

- Essay on Managerial Compensation and Wage Structure

- Essay on Wage Structure in Different Sector of the Economy

Essay # 1. Definition of Wage Structure:

Wage structure may be defined as the internal pattern of varying job ranking and basic wage rates and differentials of different categories of employees in a company according to skill, qualifications and experience. Together with this, wage structure may also be influenced by labour market forces. But the outside market impinges only at certain points in the company wage structure.

There is a great array of semi-skilled and unskilled production jobs that are specific to a particular industry or even a particular company. Workers are usually not recruited into these jobs from the outside, but work up from within the company on a seniority basis. These types of jobs, if not easily available elsewhere, wage rates become subject to inside market.

Essay # 2. Factors Affecting Wage Structure:

The wage structure in a modern plant may be influenced by the following factors:

(i) Collective bargaining and labour relations

(ii) Management discretion and custom

(iii) Skill and production operation sequence

(iv) Job evaluation or job rating

(v) Minimum wage legislation

(vi) Dearness allowance

(vii) Bonus

(viii) Wage incentives

(ix) Wage differentials

(x) Company wage policy

(xi) Governmental wage fixation methods

(xii) Tripartite convention

(xiii) ILO convention.

Wage structure may be industry based or there may be inter-industry wage structure or Federation level wage structure. In India, wage structure for different industries has been set on the basis of Government wage regulation, and tripartite negotiation.

Essay # 3. Theories of Wage Structure:

The classical economists were of the view that wage ultimately gets settled at the subsistence level, a level determined by custom. The two main assumptions underlying this view are the Malthusian Theory of Population and a fixed amount earmarked from the national dividend as wage fund. The wage fund is an amount set apart by the entrepreneur towards the payment of wage bill.

It is, according to the classical economists, fixed in quantity once for all. Therefore whenever the supply of labour increases, the wage per head goes down and with a decrease in the supply of labour the wage goes up. If the wage is above the subsistence level, population tends to increase bringing down the wage level and vice versa.

Wage level ultimately settles down at the subsistence level. The classical analysis of wage determination relies more on the supply side of the picture. Though Marx stresses the influence of ‘bargaining power’ on the level of wages, he also believes that, under capitalism, wage tends to be at subsistence level due to the substitution of machinery for labour which helps to maintain ‘reserve army’.

The Marginal Productivity Theory looked at distribution as a relationship between the marginal product of the factor and the demand for it. Marginal Productivity Theory is an extension of marginal utility analysis. The firm combines the various factors of production in such a way as to maximise its profits just as the consumer varies the combination of goods to maximise his utility.

In doing so the entrepreneur, as a logical deduction, pays each factor of production according to its marginal physical productivity. This theory says that wage, the price paid to labour, thus should be equal to its marginal productivity expressed in terms of value.

Wage rate will be higher when the marginal productivities are higher and vice versa. It is the marginal revenue product of labour that establishes its demand schedule.

This theory stresses the demand side; the supply side is only indirectly accounted for. Secondly, Marginal Productivity Theory concentrates more on ‘how much labour would be employed at a particular wage’ than how the wage rate is determined and what are all the factors that influence such determination.

This is evident from the fact that it is based on the neoclassical idea of isoquants where it is assumed that there is perfect substitutability between capital and labour.

It tries to bring out the demand schedule for labour under an assumption of labour being the only variable factor. If that is so it implies that capital is malleable in the sense that the same amount of capital can be stretched or contracted in such a way that any number of labourers can work with it.

In reality we find that there is a definite relationship between capital input and labour input irrespective of whether the technique is primitive or sophisticated.

Even if capital is expressed in money terms, the problem cannot be solved because whenever the technique is changed from a capital intensive to a labour intensive one, additional costs in terms of money and time are involved in converting the existing capital good into the other one.

Above all, measuring the marginal productivity of labour itself is not possible as production is the result of coordination between labour and capital. It is not possible to keep capital constant and increase the labour content in order to know the marginal productivity of labour. That is why probably the Marginal Productivity Theory is considered more as a statement of demand side than a theory of wages.

Reservation price of labour dictated by custom or need or the trade union action does not have much of a place in the theory. Marginal productivity theory, as Dunlop says, ‘cannot be applied to the complexities of wage structures’ also.

It may be true that wages tend to measure the marginal productivity of labour, but it cannot be a theory of wage rate determination; wage according to this theory depends upon the marginal productivity of labour but at the same time it is also true that the productivity of labour depends upon the wage that the labourer receives.

In the context of industrialisation and economic development, it is found that the institution of collective bargaining has been playing an important role in wage-setting in the areas where labour is organised. Government, through legislative measures, like the Minimum Wages Act, is another institution that has considerable influence on wage-setting.

On the other hand we have the policy of the management in a capitalist economy where the management works with the profit motive. Hence these are the three institutions that determine the rate of wages. What determines the structure of wages among firms, industries, occupations and other sectors is the other question that the theory of wages is expected to answer.

Essay # 4. Reformation of Wage Structure:

i. Wage Policy:

The main aim of wage policy is to bring wage structure in conformity with the expectations of the working classes and in the process, to maximise wages and employment. Wage changes beyond a certain level must reflect productivity changes. Any substantial improvement in real wages, which is an important objective of wage policy, cannot be achieved without increasing productivity.

Wage policy has to be framed taking into account such factors as the price level which can be sustained, the employment level to be attained at requirements of social justice, capital formation needed for the future growth of the economy, and the pattern of income generation and its distribution.

Wage policy should foster an appropriate choice of techniques so as to maximise employment at rising levels of productivity and wages. Wage policy should be so designed as to check living costs from rising.

It may be possible to fix a regional minimum for different homogenous regions in each state. Need based minimum wages can be introduced keeping in mind the extent of the capacity of the employer to pay the same. Every organised worker has a claim to this minimum. Prices constitute an important indicator of the economic health of a nation. They exercise a profound influence on the economy of a country.

During the last several years, the inflationary trends in India have inflicted a great hardship on the workers with rising prices, the cost of living of the workers also increased leading to a persistent demand for higher wages.

Ever rising prices exercise a retarding influence on economic growth. In order to secure economic development with stability, all possible efforts should be made to prevent any further rise in prices of essential goods.

The prime interest of workers is fair wages, satisfactory conditions of work such as security of service, justice and fair play. In a developing economy, wage policy is faced with a real conflict between the needs of workers for larger consumption and the demands of the company for a higher rate of capital formation.

The rate of progress has to be determined not only by the needs of the workers but also by the limitations of the national resources.

ii. Wages and Productivity:

The proposition that linking wages with productivity provides a generally agreed basis for wage adjustment. There seems no general consensus on the linking of wages with productivity. Industrial production had also risen by about 10 per cent in 1976-77 and perhaps by another 6 per cent in 1976-78. It was obvious that industrial production per man had gone up recently and productivity also had increased.

Workers ought to switch over to a wage augment based on productivity per man. There is no tradition yet in India for demanding a wage increase according to profitability and productivity per man, the unions might not change their basis for bargaining.

As wage increases in India had been linked to the cost of living rather than productivity, there have been reasons for regional differences in wages of similar workers, since the cost of living rose differently in different parts of the country.

Corrections in wage rates for the cost of living changes should be regional in character. There is a point in not having a national but a regional wage and regional wage structures in a few regions would probably be ideal. The basic issue of the rationality of a wage structure is that wages in order to be just would have to be related to the productivity of workers.

iii. Bonus:

This also has become a subject of persistent dispute between management and the workmen.

It is rather ironic that while bonus was intended to give a sense of partnership to labour in industry and help the identification of workmen with the welfare of the industry, it has been responsible for some of the major strikes in industry and has often hundred the establishment of harmonious relations between the workmen and the employers.

As far as raising the minimum bonus from 4 per cent to 8.33 per cent is concerned, this decision has been taken on political consideration rather than on merit. However, once the workmen have come to enjoy 8.33 per cent as minimum bonus, it will be a practical wisdom to restore the same.

iv. Wage Motivation and Productivity:

In some quarters, it is felt that wage should not be linked with productivity until workers are given need based wages and financial motivation through sharing the gains of productivity, is not effective unless it is preceded by psychological motivation.

National Productivity Council, in the guidelines, has clearly stated that sharing the gains of productivity should be regarded more as a philosophy of industrial relations rather than a statistical technique or a mathematical formula of distribution of gains.

In reality, no person would deny the fact that workers should get need based wage. The economy has to be geared at a faster rate to fulfill this objective. Productivity also helps considerably to improve the wage level of workmen. If an industry prospers through increased productivity, the employees should be given due share in the prosperity of an industry.

Some felt that wages should definitely be linked to productivity where even the minimum wages for a fair day’s work should be linked to certain minimum norms of output. As for higher production or work output beyond the minimum, payment by results systems arty be used.

There are different ways of linking wage with productivity. National Productivity Council has developed eleven different models for this purpose. These models can be changed according to the need of an organisation. Different systems of payment by results could be considered to increase productivity if it is preceded by psychological motivation.

Essay # 5. Distortion in Wage Structure:

In the developed countries, several studies have demonstrated the importance of economic variables in determining the wage structures. In India, studies have been neglected. This may be partly due to paucity of data. Wage structure is grossly distorted so that different industries and professions are divided into water-tight compartments, with wages bearing no relation to one another.

As a result, workers of the same category may be getting different wages. The classic example is one of wage levels of unskilled workers in the organised and unionized industries, and those in unorganised and un-unionized sectors. Even with two main sectors, there are different wage payments for the same or similar work.

This glaring distortion is to be found in case of organisations which often maintain two different rates for workers doing the same job, one for regular employees and another for workers employed on a daily wage basis.

Even in the case of the Government, the minimum pay of class IV employee is almost double of that prescribed for a daily wage earner; and this without any consideration for holidays, house rent allowance, medical facilities and provision for pension. Another example is that of high payments made by foreign companies which bear no relation to and are much higher than, the wage paid in domestic companies.

The huge differentials exist between different types of wages as also of salaries. Top salaries in enterprise, net of income tax, are often sixteen to eighteen times as high as wages of unskilled workers. If to this, perquisites, such as free house or cheap houses and subsidized travelling or free travelling, are added the differential would be higher still.

Within the organised sector, the wage levels are determined more by unionized action. Outside the organised sector, workers are paid wages which are almost equal to distress selling of labour. It is, therefore, clear that wage structure is a haphazard one, and is full of incompailities and imbalances.

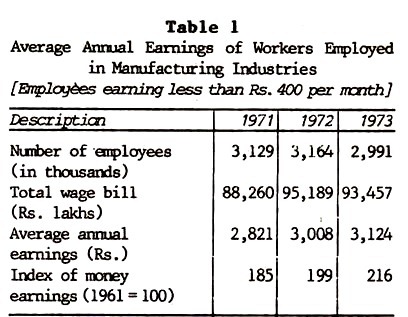

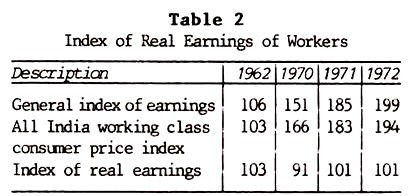

The picture is equally unsatisfactory when we view the levels of wages and earnings as also movements in them. The following two tables are self- explanatory in this respect.

The general picture that emerges in respect of levels of wages is that these are low for many and the rise in them is only in money terms, with real wages not rising. For years before 1969, the National Commission on Labour (1969) too concluded that increases in money wages of industrial workers since Independence have not been associated with a else in real wages.

Essay # 6. Managerial Compensation and Wage Structure:

The problem of managerial compensation deserves careful consideration as the compensation structure is closely linked with managerial performance and in turn, overall functioning of the enterprise. The effective functioning of an organisation very much depends on the quality, calibre and motivation of its managers.

The effectiveness of a group of people in accomplishing its desired goal is directly proportional to the effectiveness with which a group is managed. A well thought out management compensation plan is essential to attract man who is competent to attain company objective and to motivate them to seek even greater responsibility in the company.

The goals in all wage and salary administration centre on attracting, motivating and holding competent personnel. As such managerial compensation may have many features in common with wage and salary administration for rank and file workers, yet it involves certain peculiar problems of its own.

Managerial jobs after all require a great deal of decision making, planning and supervision of others, yet these special managerial skills are often difficult to define, measure or reduce to degrees that are required by most forms of job evaluation.

Another feature of managerial compensation is heavy reliance on fringes as furnished accommodation, transport, telephone etc. Further, the details of salaries for managers are generally kept secret.

Salaries of managerial and supervisory personnel confirm the well known concept that executive salaries are attached to the persons and not to the positions. As such a manager occupying a particular position in an organisation may not get the same remuneration as his predecessor.

These variations, however, should not prevent the fixation of a salary scale for each position. Different persons may be fixed at different profits in the scale and this will provide sufficient scope for varying individual salaries.

In the private sector, the remuneration of the top executive, who is usually called the Managing Director, is governed by the provisions of the Companies Act 1956. According to the provisions of the Act, approval of the Government has to be obtained for remuneration payable to Managing Director.

The remuneration is subject to a ceiling of 5 per cent of the net profits. However, while approving the remuneration, the Government takes into account several other considerations also, besides net profits. Professional or technical qualification of the persons appointed to the top position is, however, also important.

What is needed is a clear cut policy in regard to the rate of neutralisation for rise in the cost of living. Whatever may be the scheme of neutralisation, the interests of lower wage employees should receive prior consideration and they should be given a professional treatment.

A substantial part of the dearness allowance currently paid may be merged with the basic wage. Increasing efforts may be made to link wages with productivity.

Prior to this, suitable methods for measuring productivity be evolved which should have the approval of the employees. Selective incentive schemes may be evolved and introduced as early as feasible. This will improve manpower utilisation and stimulate human exertion to provide a positive motivation to greater output.

Definite salary scales be provided for various categories of managerial and supervisory personnel. Salary grades should relate to position (category). This step will also help the units in preparing career plans for the supervisory staff and identify potential for development.

Organisational morale cannot be maintained at high level without a fair, equitable and sound remuneration programme both for managers and workers. In order to promote optimal employee morale and satisfaction with company wage and salary administration, the progranme must be objective, scientific and impartial.

Only far sigh ted management fully appreciates the importance of a satisfactory remuneration policy.

Adequate remuneration system Increases Company’s production and profits lead to a reduction in production cost and make procurement and development of personnel effective. They increase their earning, improve their efficiency, enhance their morale and improve their relationship with employers.

Essay # 7. Wage Structure in Different Sector of the Economy:

An empirical analysis of the various factors that influence the wage structure in different sectors of the economy plays a crucial role in the formulation of national wage policy. The available statistical data on wage rates in Indian economy clearly shows that the average rates of wages vary significantly among different industries, different occupations and different regions.

An important area of empirical investigation in the field of wage structure in India in which, several studies have already been made, has been the analysis of inter-industry wage differentials in the organised manufacturing sector.

The theoretical framework that is developed for explaining the inter-industry wage differentials consists mainly of two basic hypotheses.

The first hypothesis, which may be called ‘the expected ability to pay hypothesis’ has been advanced by David G. Brown, who argues that “wage level differences among manufacturing industries result primarily from industry-by-industry differences in the employers estimates of their future abilities to pay wages”.

The other hypothesis, which may be called ‘ the technology hypothesis’, is based on the premise that the technological levels of different industries vary considerably at any given point of time which in turn implies that the skill mix of the working force employed in different industries would vary giving rise to inter-industry differentials in the average wage rates computed for each industry taken as a whole.

In a recent study, this has been examined as the problem of inter-industry wage structure from the viewpoint of the technology hypothesis, and it is argued that “technological advance requires not only a larger component of skill in the work force, but it also leads to greater degree of skill differentiation and specificity of jobs in industries. It has also been argued in a recent study on occupational wage structure that the job content technologically determined, would be the basis for occupation rates which in turn would be reflected in the average rate of a plant or industry”, which implies that, while economic factors and institutional forces affect the wage structure, “the primacy of technologically determined wage differentials as the base of wage structures still remains to be reckoned with”.

The basic source of data for the empirical studies on inter industry wage structure has been the Annual Survey of Industries (ASI) and often their scope has been confined to the factories falling under the census sector of ASI. Moreover, most of the studies define an industry at the two-digit level of aggregation, though a few studies have also examined the industries at the four-digit level of aggregation.

However, almost all of these studies have examined the wage structure covering the entire manufacturing sector. Few attempts seem to have been made to apply the above theoretical framework to compare the extent of wage differentials and its major determinants for the broad categories of consumer goods industries and capital goods industries within the organised manufacturing sector.

Such a comparison would be an interesting one to make because there are fundamental differences between the consumer goods industries in regard to technology levels, scale of operation and several related characteristics which would in turn play a significant part in shaping the wage structure in these two broad categories of industries.

Therefore, this case-study has been made to examine the wage structure in consumer goods industries in relation to that in capital goods industries falling under the registered manufacturing sector of the Indian economy.

The study is divided into four parts. The first part brings out two tentative hypotheses that can be advanced in respect of the relative wage structures in the consumer goods and the capital goods industries. The second part examined the first hypothesis by analysing the extent of wage differentials observed for the two types of industries.

In the third part, an attempt has been made to test the second hypothesis by assessing the relative importance of major factors influencing the wage structure in the two categories of industries. Finally, the fourth part summarizes the main findings of the study.

On the basis of the technology hypothesis which states that the industry wage rates vary mainly on account of inter-industry technological differences, we should expect the average wage rate in the consumer goods industry to be lower than that in the, capital goods industries and also the former to show greater degree of variation than the latter.

The technological levels of a large number of consumer goods industries, most of which would have scarred in the pre-industrial stage of the economy, are likely to be low especially in relation to those found in the capital goods industries. By and large, the capital goods industries make use of the modern technology which requires a higher level of capital intensity and a larger component of specific skills in the working force.

Moreover, in terms of both the minimum amount of investment required in machinery and equipment per person employed as well as the proportion of skilled workers required to carry out the production process different types of capital goods industries are likely to show a relatively greater degree of similarity or homogeneity as compared to the category of consumer goods industries which cover a wide range of industries producing a variety of products.

Once the process of industrialisation and economic growth has already started, the further development of consumer goods industries takes place not only along the line of expansion but equally along the lines of diversification and introduction of new products.

This process of development of consumer goods industries is governed to a considerable extent by the forces of demand, and, evidently, the pattern of demand is determined largely by the pattern of income distribution.

With rapidly growing income levels, the extreme income inequalities, which might have existed even earlier, assume new dimensions when we look at them in absolute rather than relative terms.

Hence, we would generally find that the broad category of consumer goods industries would consist of some industries which use high level technology to produce sophisticated luxury goods for the rich and some industries which use traditional or low level technology to produce the kind of goods that would meet the requirements of low income groups in different regions.

Thus, the category of consumer goods industries would show a greater degree of variation in technology levels.

On the basis of the considerations, we can formulate the following hypotheses about the relative wage structures in the consumer goods and the capital goods industries:

The average wage rate observed in the consumer goods industries would show a higher degree of variation around a relatively lover mean value as compared to the capital goods industries where the average wage rate would show lower variability around a relatively higher mean value.

The inter-industry wage differentials within the category of capital goods industries would be determined primarily by the expected ability to pay whereas the inter-industry wage differentials within the category of consumer goods industries would be determined by both types of factors, viz., the expected ability to pay as well as the technology differentials, taken together.

In what follows, an attempt has been made to test these two hypotheses in the case of Indian manufacturing industries falling under the two broad categories on the basis of the relevant cross-section data for the year 1975-76.

For measuring the extent of wage differentials in consumer goods and capital goods industries, we have used the data available from the latest Report of Annual Survey of Industries which relates to the year 1975-76.

We have covered both the census sector factories as well as the sample sector factories reported in ASI 1975-76, we have also distinguished between industries as a somewhat disaggregated level by treating the industries reported at the three-digit level of aggregation as separate industries, rather than confining to the highly aggregative two digit level classification of industries.

We have, however, excluded from the purview of present analysis those of the three digit level industries which are relatively small or less developed and provides employment to less than two thousand persons. Our analysis is, therefore, based on the data relating to 63 industries in the registered manufacturing sector which provide employment to more than two thousand employees.

These 63 industries specified as the three digit level of aggregation constitute the category of relatively high employment generating industries which had almost four-fifths of the total number of workers employed in the registered manufacturing sector in the year 1975-76.

Of these 63 industries, 36 industries belong to the broad category of consumer goods industries while the remaining 27 industries fall under the category of capital goods industries.

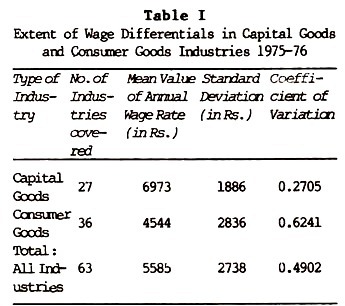

Table I shows the average wage rate and the extent of absolute and relative wage differential in consumer goods and capital goods industries observed in the year 1975-76.

We find that the mean value of the industry wage rate observed in the consumer goods industries turn out to be only two-thirds of the corresponding mean value for the capital goods industries, whereas the absolute wage differential as measured by the standard deviation of the industry wage rate around the mean value in the former is one and a half time as large as that observed in the case of the latter.

Consequently, we can see from the Table that the extent of relative wage differential, as measured by the coefficient of variation, can be regarded as moderate or relatively low in the case of capital goods industries, whereas it is quite high in the case of consumer goods industries.

It is obvious that the above observation regarding the wage structure in the capital goods and consumer goods industries in India lend support to our first hypothesis which states that the wage rate in capital goods industries will tend to be, on an average, higher in its value and it will reflect less variability as compared to the wage rate in consumer goods industries which will be marked by a high degree of variability.

Moreover, it follows from this analysis that the relatively high degree of variability revealed by the industry wage rate in the organised manufacturing sector taken as a whole is due not only to the overall wage differential between the consumer goods and capital goods industries, but also to the high extent of wage differentials that exist within the category of consumer goods industries.

To assess the relative importance of various factors which determine the extent of inter- industry wage differentials, we have to postulate a functional relationship between the industry wage rate and a set of explanatory variables which are deemed to be significant in shaping the wage structure.

According to the theoretical framework developed for explaining inter-industry wage differentials, which is already outlined above, the explanatory variables that we specify should indicate either the expected ability to pay or the level of technology at which each industry operates.

The main proxy variables which are generally used for measuring the expected ability to pay are average productivity of labour and average number of persons employed per factory in each industry. Similarly, the variables that can be used as a proxy for the technology levels are average levels of capital intensity and capital output ratio in each industry.

Thus, we can postulate the following functional relationship.

W = f (P, F, K, V) where

W = average annual wage rate in a given industry measured as the ratio of total wages and salaries paid during the given year to the total number of persons employed during the year;

P = average productivity of labour measured as the ratio of total value added to the total number of employees;

F = average size of factory measured as the ratio of total number of employees to total number of factories;

K = average level of capital intensity measured as the ratio of total value of fixed capital assets to total number of employees;

V = average capital output ratio measured as the ratio of total value added to total value of capital stock employed in a given industry.