The following points highlight the seven major growth strategies that are listed below which are relevant in the early stage of potential- development.

1. Hold relative position in high-growth products/markets:

The growth associated with this strategy is directly attributable to the growth in demand for the product/service being produced by the firm.

The funds necessary to support the growth typically come from:

(i) Operations,

(ii) Debt financing, and

(iii) Periodical equity financing, particularly when the growth rate is high.

Ability to remain competitive in terms of product development, promotion and advertising, and distribution as well as in terms of productive capacity is the key to this strategic choice. A principal risk inherent in this strategy is that a competitor may embark on a pre-emptive strategy designed to capture market share.

This risk is relatively high when the product is in about the mid-range of the growth stage of product life cycle. Under these circumstances, all competitors see the market having high growth potential and take the risk of developing production and distribution capacity well in excess of current demand levels.

Those firms which have the greatest capacity to assume the financial risks associated with pre-emptive capacity expansion are most likely to adopt this strategy.

2. Increase market share in high-growth market:

This strategy is highly suitable for commodity-type products. Essential to the success of this strategy is ‘getting there first’, while being careful to make sure that competitors know the firm has started so that they will be less tempted to commit themselves to the same strategy at the same time.

This strategy demands management’s ability to significantly differentiate the products from those of competitors, associated with aggressive investment in advertising, and distribution, etc.

3. Increase market share in mature markets:

Two major approaches are seen to be employed to capture market share in slow-growth markets.

These are as follows:

(i) Rationalising production in a way that will achieve cost leadership, and thereby yielding higher margins than those enjoyed by competitors. Reducing the number of models in the product line and taking market-related competitive moves such as ‘price-cut’ are envisaged in this approach.

(ii) Segmenting the market in search for high-growth potential segments and reallocating resources to those segments that will result in a product-mix—which in the aggregate is superior to that of competitors in terms of growth potential.

4. Hold strong relative position in mature market; use ‘Excess’ cash flow, funds capacity and other resources to support penetration of multinational markets with existing product line:

Any management deciding on this strategy typically expose its firm to a wide variety of patterns of opportunity and risk.

Each foreign country has its unique pattern of culture, social and economic development, and politics which often requires the development of unique approach to market penetration and development. Failure to differentiate these unique characteristics, in a great measure, of each potential country’s market can lead to poorer results than expected.

For most Indian managements, moving their firm’s resources into the multinational market arena opens a bewildering array of new uncertainties, including complexities of international money markets and global politics.

5. Hold strong relative position in maturing market; use ‘excess’ cash flow, external funds capability, and other resources to support penetration of new product/ market areas domestically:

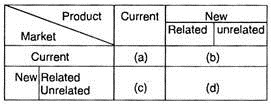

We should consider the Product-Market Matrix (depicted below) with a view to studying the position of a firm in relation to this strategy.

The stated strategy refers to box (d) in the matrix, which, according to Ansoff, again refers to the increase of a firm’s activities for ‘diversification’—a strategy for growth and expansion.

The management of a firm deciding to follow this strategy can do so either by developing new products internally or by acquiring firms with already developed products and perhaps, market positions. The latter approach is typically the faster and less risky. It, however, requires larger initial investment.

Successful new-product development needs to have competence in marketing, production and finance, and also in research and development. Yet, if a firm feels constrained in either marketing or R & D—it can decide to acquire either of them rather than internally develop new products/markets.

Typically, technological capability of a firm is important. For firms with very ‘old’ well-established technology, internal new-product development will often bear disappointing fruit in terms of growth and profit potential, as most of the business opportunities with growth potential that could be developed with that technology have already been discovered and developed by other firms.

The management of a firm which decides on a strategy of product-market diversification through acquisition must further decide on whether such diversification must be related to its existing functional resources and capabilities, essentially unrelated.

In case of related diversification, each acquisition must be regarded as an extension to one or more of the existing functional resources or capabilities of the firm (e.g., marketing, production, R & D).

‘Synergistic’ effects must be identifiable in each acquisition (i.e., effects which indicate that the combination of firms which results from the acquisition has stronger performance potential than the sum of their performance potentials before the acquisition).

In unrelated diversification strategies, no attempt is made to build on or extend the existing functional resources and capabilities of the acquiring firm outside the areas of finance and managerial systems.

Each acquisition in a pure unrelated diversification strategy is analysed exclusively as a portfolio investment decision. So long as the criteria of shareholders’ wealth improvement and a risk-return balance are met, an acquisition can be justified under this type of strategy.

Though increasingly and widely adopted by some firms during the 1970’s as a growth strategy, unrelated diversification has come under serious attack by governmental regulations.

Again, unrelated diversification as a growth strategy is most often considered by managers of firms who have found it difficult to identify significant growth potential in related areas. From their point of view, they either have to forego attempting to achieve their desired level of growth for the firm or adopt an unrelated diversification strategy.

To offset this dilemma, managers are adopting a course what might be termed a ‘linked’ unrelated diversification strategy. That is, after an initial investment in one or more unrelated areas, all subsequent acquisitions must be linked, or related, to the newly acquired resources and competences.

6. Hold strong relative position in multinational markets with present product line; use ‘Excess’ cash flow, funds capability, and other resources to diversify products:

This strategy leads to the formulation of the multi-market/multi-product strategies. The approach of it is that: having already achieved geographic market diversification, managers striving for further growth for their firms must begin to think about product diversification.

The basic options as to how to do this are the same as those indicated under strategy 5 above. But another dimension needs to be considered—the added dimension of complexity stemming from geographic diversity in the present operations. The fact is that from one geographic area to another, opportunities for successful product diversification are quite likely to vary significantly.

In such situations, two approaches are suggested by the strategists:

(i) The management may choose to allow wide variation in product diversification moves between geographic areas; or

(ii) The management may choose to identify one of several product diversification moves which provide varying amounts of opportunity in the various geographic areas.

Making a choice in favour of the first approach is sure to result in increased diversity in products and markets to be served and managed.

The advantage with a choice of the second approach is that it limits opportunity but provides management with less diversity in products to manage, and, thus, with potentially greater control over the development of the firm.

Again, for multimarket/multiproduct strategy, an organisation is faced with complex issues. Such issues are: Should the basic organisation structure be product-centred or geographic-centred?

How should the differing views of the geographically specialised managers be coordinated and integrated with those of the product and functionally specialised managers? Should some form of matrix structure be used to generate and follow strategic plans? If so, how should this matrix planning structure be integrated with the line operating structure?

7. Hold strong relative position in diversified product-line domestically; use ‘Excess’ cash flow, funds capability, and other resources to diversify markets:

With this strategy, corporate managers view each of the product lines as in growth strategy 4 indicated above. Several product lines instead of one product line pose additional complexity here. Thus, plans for geographic expansion in relation to one product line must be carefully integrated from all functional and geographic perspectives with such plans for the other product lines.

In relation to this growth strategy, organisational problems and issues envisaged with the growth strategy 6 have also to be given serious consideration.