Industry factors have been found to play a dominant role in the performance of many companies, with the exception of those that are its notable leaders or failures. As such, one needs to understand these factors at the outset before delving into the characteristics of a specific firm.

Michael Porter, a leading ‘authority on industry analysis, proposed a systematic means of analyzing an industry’s potential profitability known as Porter’s “five forces” model. According to Porter, an industry’s overall profitability depends on five basic competitive forces, the relative weights of which vary by industry.

1. Intensity of Rivalry among Incumbent Firms

2. Threat of Entry

3. Pressure from Substitute Products

4. Bargaining Power of Buyers

5. Bargaining Power of Suppliers

These five factors combine to form the industry structure and suggest profitability prospects for firms that operate in the industry.

Each of the factors are discussed below:

1. Intensity of Rivalry among Incumbent Firms:

Competition intensifies when a-firm identifies the opportunity to improve its position or senses competitive pressure from other businesses in its industry, which can result in price wars, advertising battles, new product introductions or modifications, and even increased customer service or warranties. The intensity of competition often evolves over time and depends on a number of interacting factors.

i. Concentration of Competitors:

The number of companies in the industry and / or their relative sizes or power levels influences an industry’s intensity of rivalry. Industries with few firms tend to be less competitive, but those with many firms that are roughly equivalent in size and power tend to be more competitive, as each firm fights for dominance. Competition is also likely to be intense in industries with large numbers of firms because some of those companies may believe that they can make competitive moves without being noticed.

ii. High Fixed or Storage Costs:

When firms have unused productive capacity, they often cut prices in an effort to increase production and move toward full capacity. The degree to which prices (and profits) can fall under such conditions is a function of the firms’ cost structures. Those with high fixed costs are most likely to cut prices when excess capacity exists because they must operate near capacity to be able to spread their overhead over more units of production. The U.S. airline industry experiences this problem periodically, often resulting in last-minute fare specials in an effort to fill seats that would otherwise fly vacant.

iii. Slow Industry Growth:

Firms in industries that grow slowly are more likely to be highly competitive than companies in fast-growing industries. In slow-growth industries, one firm’s increase in market share must come at the expense of other firms’ shares. Competitors often place more attention to the actions of their rivals than to consumer tastes and trends when formulating strategies.

iv. Lack of Differentiation or Low Switching Costs:

The more similar the offerings among competitors, the more likely customers are to shift from one to another. As a result, such firms tend to engage in price competition. When switching costs- one-time costs that buyers incur when they switch from one company’s products or services to another-are low, firms are under considerable pressure to satisfy customers who can easily switch competitors at any time. When products or services are less differentiated, purchase decisions are based on price and service considerations, resulting in greater competition.

Interestingly, firms often seek to create switching costs in efforts to encourage customer loyalty. Internet Service Provider (ISP) America Online, for example, encourages users to obtain and use AOL e-mail accounts. Of course, these accounts are eliminated if the AOL. Customer decides to switch to another ISP. Frequent flier programs also reward fliers who fly with ‘one or a limited number of airlines. Southwest Airlines’ generous program rewards only customers who complete a given number of flights within a 12-month period, thereby effectively raising the costs of switching to another airline.

v. Capacity Augmented in Large Increments:

When production can be easily added one increment at a time, overcapacity is not a major concern. However, if economies of scale or other factors dictate that production be augmented in large blocks, then capacity additions may lead to temporary overcapacity in the industry, and firms may cut prices to clear inventories. Airlines and hotels, for example, usually must acquire additional capacity in large increments because it is not feasible to add a few airline seats or hotel rooms as demand warrants.

vi. Diversity of Competitors:

Companies that are diverse in their origins, cultures, and strategies often have different goals and means of competition. Such firms may have a difficult time agreeing on a set of “competitive rules:” As such, industries with global competitors or with entrepreneurial owner-operators tend to be particularly competitive. Internet businesses often “change the rules” for competition by emphasizing alternative sources of revenue, different channels of distribution, or a new business model. This diversity can increase rivalry sharply.

vii. High Strategic Stakes:

Competitive rivalry is likely to be high if firms also have high stakes in achieving success in a particular industry. For instance, many strong, traditional companies cannot “afford” to fail in their web-based ventures if their strategic managers believe a web presence is necessary even if it is not profitable. These desires can often lead a firm to sacrifice profitability.

viii. High Exit Barriers:

Exit barriers are economic, strategic, or emotional factors that keep companies from leaving an industry even though they are not profitable or may even be losing money. Examples of exit barriers include fixed assets that have no alternative uses, labour agreements that cannot be renegotiated, strategic partnerships among business units within the same firm, management’s unwillingness to leave an industry because of pride, and governmental pressure’ to continue operations to avoid adverse economic effects in a geographic region. When substantial exit barriers exist, firms choose to complete as a “lesser of two evils,” a practice that can drive down the profitability of competitors as well.

2. Threat of Entry:

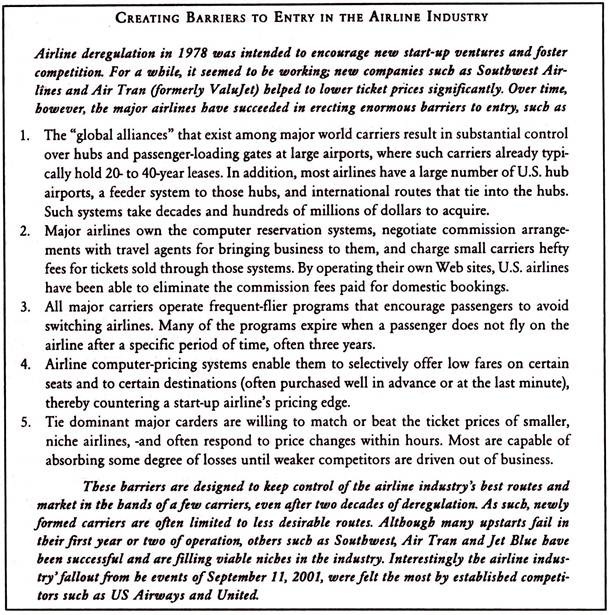

An industry’s productive capacity expands when new competitors enter. Unless the market is growing rapidly, new entrants intensify the fight for market share, lowering prices and, ultimately, industry profitability. When large, established, firms control an industry, new entrants are often pelted with retaliation when they establish their operations or begin to promote their products aggressively.

For example, when Dr. Pepper launched Like Cola directly against Coke and Pepsi, an effort to make inroads into the cola segment of the soft drink market, the two major competitors responded with strong promotional campaigns to thwart the effort. If prospective entrants anticipate this kind of response, they are less likely to enter the industry in the first place. As such, entry into an industry may well be deterred if the potential entering firm expects existing competitors to respond forcefully. Retaliation may occur if incumbent firms are committed to remaining in the industry or have sufficient cash productive capacity to meet anticipated customer demand in the future.

The likelihood that new firms will enter an industry is also contingent on the extent to which barriers to entry have been erected- often by existing competitors-to keep prospective newcomers out.

i. Economics of Scale:

Economics of scale refer to the decline in unit costs of a product or service that occurs as the absolute volume of production increases. Sales economics occur when increased production drives down costs and can result from a variety of factors, most namely high firm specialization and expertise, volume purchase discounts, and a firm’s expansion into activities once performed at higher costs by suppliers or buyers.

Substantial economies of scale deter new entrants by forcing them either to enter at industry at a large scale-a costly course of action that risks a strong reaction from existing firms-or to suffer substantial cost disadvantages associated with a small-scale operation. For example, a new automobile manufacturer must accept higher per-unit costs as a result of the massive investment required to establish a production facility unless a large volume of vehicles can be produced at the outset.

ii. Brand Identity and Product Differentiation:

Established firms may enjoy strong brand identification and customer loyalties that are based on actually or perceived product or service differences. Typically, new entrants must incur substantial marketing and other costs over an extended period of time to overcome this barrier. Differentiation is particularly important among products and services where the risks associated with witching to a competitive product or service are perceived to be high, such as over-the-counter drugs, insurance, and baby-care products.

iii. Capital Requirements:

Generally speaking, higher entry costs tend to restrict new competitors and ultimately increase industry profitability. Large initial financial expenditures may be necessary for production, facility construction, research and development, advertising, customer credit, and inventories. Some years ago, Xerox cleverly created a capital barrier by offering 0 lease, not just sell, its copiers. As a result, new entrants were faced with the task of generating large sums of cash to finance the leased copiers.

iv. Switching Costs:

Switching costs are that upfront costs that buyers of one firm’s products may incur if they switch to those of a competitor. If these costs are high, buyers may need to test the new product first, make modifications in existing operations to accommodate the change, or even negotiate new purchase contracts. When switching costs are low-typically the case when consumers try a new grocery store-change may not be difficult. When switching costs are high, however, customers may be reluctant to change.

For example, for a number of years, Apple has had the unenviable task of convincing IBM compatible customers not only that Apple produced a superior product, but also that switching from IBM to Apple justifies the cost and inconvenience associated with software and file incompatibility. In contrast, fast food restaurants generally have little difficulty persuading consumers to switch from one restaurant to another as new products are introduced.

In some industries, entering existing distribution channels requires a new firm to entice distributors through price breaks, cooperative advertising allowances, or sales promotions. Existing competitors may have distribution channel ties based on long-standing or even exclusive relationships, requiring the new entrant to create its own channels of distribution. For example, a number of manufacturers and retailers have formed partnerships with FedEx or UPS to transport merchandise directly to their customers. As a distribution channel, the Internet may offer an alternative to companies unable to penetrate the existing channels.

v. Cost Disadvantages Independent of Size:

Existing competitors may have developed cost advantages not related to firm size that cannot be easily duplicated by newcomers. Such factors include patents or proprietary technology, favorable locations, superior human resources and experience in the industry. For example, eBay’s experience, reputation, and technological capability in online auctions have made it very difficult for prospective firms to enter the industry.

vi. Government Policy:

Governments often control entry to certain industries with licensing requirements or other regulations. Just as individuals are not free to establish their own hospitals without regulatory approval, they cannot establish .a Web site that dispenses medical advice without the approval of regulators. Existing competitors often lobby legislators to enact policies that make entry into their industry a complicated or costly endeavor.

3. Pressure from Substitute Products:

Firms in one industry may be competing with firms in other industries that produce substitute products, offerings produced by firms in another industry that satisfy similar consumer needs but differ in specific characteristics. Even though they emanate from outside the industry, substitutes can limit the prices that firms can charge. For instance; low fares offered by airlines can place a ceiling on the long-distance bus fares that Greyhound can charge for similar routes. Hence, firms that operate in industries with few or no substitutes are more likely to be profitable.

4. Bargaining Power of Buyers:

The buyers of an industry’s outputs can lower that industry’s profitability by bargaining for higher quality or more services and playing one firm against, another.

A number of circumstances can raise the bargaining power of an industry’s buyers:

1. Buyers are concentrated, or each one purchases a significant percentage of total industry sales.

If a few buyers purchase a substantial proportion of an industry’s sales, then they will wield considerable power over prices. This is especially prevalent in markets for components and raw materials.

2. The products that the buyers purchase represent a significant percentage of the buyers’ costs. When this’ occurs, price will become more critical for buyers, who will shop for a favorable price arid will purchase more selectively.

3. The products that the buyers purchase are standard or undifferentiated. In such cases, buyers are able to play one seller against another and initiate price wars.

4. Buyers face few switching costs and can freely change suppliers.

5. Buyers earn low profits, creating pressure for them to reduce their purchasing costs.

6. Buyers have the ability to engage in backward integration by becoming their own suppliers. Large automobile manufacturers, for example, use the threat of self-manufacture as a powerful bargaining lever.

7. The industry’s product is relatively unimportant to the quality of the buyer’s products or services. In contrast, when the quality of the buyers’ products is greatly affected by what they purchase from the industry, the buyers are less likely to have significant power over the suppliers because quality and special features will be the most important characteristics.

8. Buyers, have complete information. The more information buyers have, regarding demand, actual market prices, and supplier costs, the greater their bargaining power. The advent of the Internet has increased the quantity and quality of information available to buyers in a number of industries.

5. Bargaining Power of Suppliers:

Suppliers can extract the profitability out of an industry whose competitors may be unable to recover cost increases by raising prices. The conditions that make’ suppliers powerful are similar to those that affect buyers.

Specifically, suppliers are powerful under the following circumstances:

1. The supplying industry is dominated by one or a few companies. Concentrated suppliers typically exert considerable control over prices, quality, and selling terms when selling to fragmented buyers.

2. There are no substitute products, weakening buyers in relation to their suppliers.

3. The buying industry is not a major customer of the suppliers. If a particular, industry does not represent a significant percentage of the suppliers’ sales, then the suppliers control the balance of power. If competitors in the industry comprise an important customer, however, suppliers tend to understand the interrelationships and are likely to consider the long-term viability of their counterparts -not just price-when making strategic decisions.

4. The suppliers pose a credible threat of forward integration by becoming their own customers. If suppliers have the ability and resources to operate their own manufacturing facilities, distribution channels, or retail outlets, they will possess considerable control over buyers.

5. The suppliers’ products are differentiated or have built-in switching costs, thereby reducing the buyers’ ability to play one supplier against another.

Limitations of Porter’s Five Forces Model:

Generally speaking, the five force model is based on the assumptions of the, industrial organization (IO) perspective on strategy, as opposed to the resource based perspective. Although the model serves a useful analytical tool, it has several key limitations. First, it assumes the existence of a clear, recognizable’ industry. As complexity associated with industry, definition, increases, the ability to draw coherent conclusions from the model diminishes.

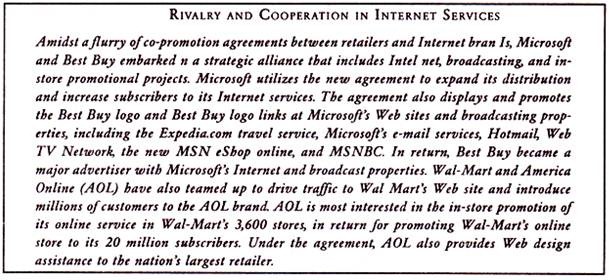

Second, the model addresses only the behavior of firms in an industry and does not account for the role of partnerships, a growing phenomenon in many industries. When firms “work together,” either overtly or covertly, they create complex relationships that are not easily incorporated into industry models.

Third, the model do not take into account the fact that some firms, most notably large ones, can often take steps to modify the industry structure, thereby increasing their prospects for profits. For example, large airlines have been known to lobby for hefty safety restrictions to create an entry barrier to potential upstarts.

Fourth, the model assumes that industry factors, not firm resources, comprise the primary determinants of firm profit. This issue continues to be widely debated among both scholars and executives. This limitation reflects the ongoing debate between IO theorists who emphasize Porter’s model and resource-based theorists who emphasize firm-specific characteristics.

Finally, a firm that competes in many countries typically must be concerned with multiple industry structures. The nature of industry competition in the international arena differs among nations, and many present challenges that are not present in a firm’s host country.

These challenges notwithstanding, a thorough analysis of the industry via the five forces model is a critical first step in developing an understanding of competitive behavior within an industry. In a general sense, Porter’s five forces model provides insight into profit-seeking opportunities, as well as potential challenges, within an industry.