This article throws light upon the top six strategies used in planning an interview. The strategies are: 1. State the Purpose 2. Get Information about the Other Party 3. Decide the Structure 4. Consider Possible Questions 5. Plan the Physical Setting 6. Anticipate Problems.

Strategy # 1. State the Purpose:

The starting point of good communication, as we’ve repeated ever so often in this book, is a clear purpose. As an interview is a communication process, here too the first step in preparing for the interview is a clear formulation of the purpose both for the interviewer as well as for the respondent.

The interviewer must have a specific goal clearly in mind, so that the structure of the interview and the actual questions can all be tailored to suit that particular purpose. On the respondent’s part, lack of a clear purpose can cause him to send out conflicting signals which often undermine his chances of achieving his goal.

Strategy # 2. Get Information about the Other Party:

Depending on the situation, you need to gather relevant information about the interviewer or the respondent. A respondent’s degree of preparation speaks volumes about his interest level and conscientiousness. In order to make the best case for your candidacy for a particular job, you need to be prepared with information about yourself and about the job, the company, and the field.

The interviewer too finds it easier to restrict himself to relevant questions if he is familiar with the details the applicant has provided in his application form or resume.

Strategy # 3. Decide the Structure:

Interviews can be structured in different ways. The structure determines what kind of planning you ought to put in and what sort of results you can expect. In a directive interview the interviewer takes almost complete charge of the flow of conversation by asking specific questions designed to keep the respondent focused on the type of information required.

Such questions are called close-ended questions, as they seek to elicit precise information on a specific issue.

A directive approach is useful when you are looking for precise, reliable information in a short time. However, a directive approach limits the respondent’s initiative and may prevent him from volunteering useful information. When you want to not only obtain factual information but gauge the underlying feelings of the respondent or draw out his opinions on different issues, a non-directive approach works better.

This approach, with its open-ended questions, gives the respondent more control in determining the course of the interview. The interviewer does a minimum of talking and encourages the respondent to fully express his feelings.

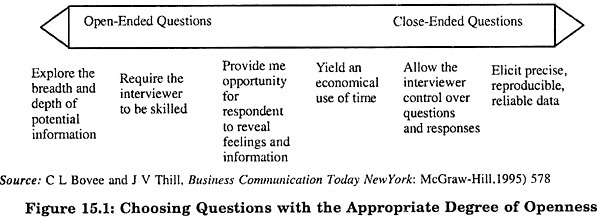

In an actual interview, most questions fall along a continuum of openness, as shown in figure 15.1. As an interviewer, you can frame a question toward any one end of the spectrum, depending on the purpose you want to achieve.

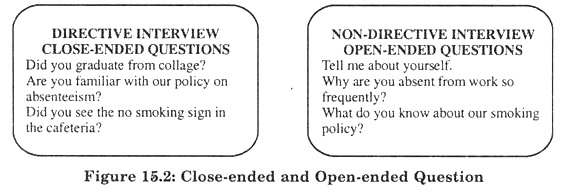

Look at these examples of close-ended and open-ended questions in figure 15.2.

Strategy # 4. Consider Possible Questions:

Once you have decided on the format, you can start formulating specific questions. Each question must be so structured as to elicit just the information you want. Apart from deciding where your questions are going to fall on the openness continuum, you can choose between factual and opinion questions, primary and secondary questions and direct and indirect questions.

Factual questions, as the name suggests, seek to ascertain facts, while opinion questions ask for the respondent’s judgments. Primary questions introduce new topics or new areas within a topic and secondary questions seek additional information on a topic that has already been introduced. Secondary questions are useful when a previous answer is incomplete, vague or irrelevant.

Direct and indirect questions are two different ways of eliciting information. Though direct questions are usually the best way to get information, sometimes they fail to elicit satisfactory answers, either because the respondent is unable to answer accurately or is unwilling to do so. In such situations indirect questions that draw out information without directly asking for it are more effective. Look at these examples.

Direct Question:

Do you understand?

Are you satisfied with my leadership?

Indirect Question:

If you had to explain this policy to a newcomer, what would you say?

If you were made the manager of this department, what changes would you make?

Apart from these, you may also decide to include hypothetical and leading questions. Hypothetical questions are ‘what if questions: If I were to introduce flexible working hours, do you think the morale of the staff would improve?

These questions can indirectly get a respondent to describe his attitudes. They also let you learn how a person would behave in certain situations. Leading questions force the respondent to answer in a particular way, by suggesting the answer the interviewer expects: You wouldn’t mind working extra hours, whenever necessary, would you?

Strategy # 5. Plan the Physical Setting:

The physical setting in which the interview takes place can have a great deal of influence on the results. A setting with the minimum distractions is generally the best. Frequent interruptions mar the flow of conservation and prevent both the interviewer and the respondent from being alert to each other’s verbal and non-verbal cues.

The seating arrangements also have an impact on the interview. An interviewer who addresses the respondent from behind a desk assumes greater control. When the two parties face each other with no barriers between them there is a greater degree of informality.

Strategy # 6. Anticipate Problems:

This is an important aspect of preparation. Once you’ve clarified your purpose, decided the format, put together your questions and decided the setting, go over the entire plan once again, looking for loopholes. Is the format you’ve selected really suitable for the achievement of your specific purpose? Perhaps you should include more questions that are open-ended, to get more details?

What if the respondent is a poor communicator and is unable to handle too many open-ended questions? What if the respondent uses open-ended questions to digress from the main point? As you plan an interview you may come up with many such questions. Answering these questions will help you to employ effective strategies to counter problems as and when they arise during the course of the interview.