This article throws light upon the top four theories of leadership. The leadership theories are: 1. Trait Theory of Leadership 2. Behavioral Theories 3. Contingency Theories 4. Transformational Leadership Theory.

Theories of Leadership: Top 4 Theories of Leadership

Theory of Leadership # 1. Trait Theory of Leadership:

In the 1940s, most early leadership studies concentrated on trying to determine the traits of a leader. The trait theory was the result of the first systematic effort of psychologists and other researchers to understand leadership. This theory held that leaders share certain inborn personality traits.

The earliest theory in this context was the “great man” theory, which actually dates back to the ancient Greeks and Romans. According to this theory, leaders are born, not made. Many researchers have tried to identify the physical, mental, and personality traits of various leaders. However, the “great man” theory lost much of its relevance with the rise of the behaviorist school of psychology.

In his survey of leadership theories and research, Ralph M. Stogdill found that various researchers have related some specific traits to leadership ability.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

These include five physical traits (such as appearance, energy and height); four intelligence and ability traits; sixteen personality traits (such as adaptability, enthusiasm, aggressiveness, and self-confidence); six task-related characteristics (such as achievement, drive, initiative and persistence), and nine social characteristics (such as interpersonal skills, cooperativeness, and administrative ability).

More recently, researchers have identified the following key leadership traits: leadership motivation (having a desire to lead but not hungry for power), drive (including achievement, energy, ambition, initiative, and tenacity), honesty and integrity, self-confidence (including emotional stability), cognitive ability, and an understanding of the business.

In general, the study of leadership in terms of traits has not been a very successful approach for explaining leadership. All leaders do not possess all the traits mentioned in these theories, whereas many non-leaders possess many of them.

Moreover, the trait approach does not give one an estimate of how much of any given trait a person should possess. Different studies do not agree about which traits are leadership traits, or how they are related to leadership behavior. Most of these traits are really patterns of behavior.

Theory of Leadership # 2. Behavioral Theories:

When it became evident that effective leaders did not seem to have a particular set of distinguishing traits, researchers tried to study the behavioral aspects of effective leaders.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

In other words, rather than try to figure out who effective leaders are, researchers tried to determine what effective leaders do – how they delegate tasks, how they communicate with and try to motivate their followers or employees, how they carry out their tasks, and so on.

In this section, we review major efforts to identify important leadership behaviors. This research grew largely out of work at the University of Iowa, the University of Michigan, and the Ohio State University. We also discuss about Likert’s four systems of management and the Managerial Grid.

Iowa and Michigan Studies:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Kurt Lewin, a researcher at the University of Iowa, and his colleagues, made some of the earliest attempts to scientifically determine effective leader behaviors. They concentrated on three leadership styles: autocratic, democratic, and laissez-faire.

The autocratic leader tends to make decisions without involving subordinates, spells out work methods, provides workers with very limited knowledge of goals, and sometimes gives negative feedback.

The democratic or participative leader includes the group in decision-making; he consults the subordinates on proposed actions and encourages participation from them. Democratic leaders let the group determine work methods, make overall goals known, and use feedback to help subordinates. Laissez-faire leaders use their power very rarely.

They give the group complete freedom. Such leaders depend largely on subordinates to set their own goals and the means of achieving them. They see their role as one of aiding the operations of followers by furnishing them with information and acting primarily as a contact with the group’s external environment. They too avoid giving feedback.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

To determine which leadership style is most effective, Lewin and his colleagues trained some persons to exhibit each of the styles. They were then placed in charge of various groups in a preadolescent boys’ club. They found that on every criterion in the study, groups with laissez-faire leaders under performed in comparison with both the autocratic and democratic groups.

While the amount of work done was equal in the groups with autocratic and democratic leaders; work quality and group satisfaction was higher in the democratic groups. Thus, democratic leadership appeared to result in both good quantity and quality of work, as well as satisfied workers.

Later research, however, showed that democratic leadership sometimes produced higher performance than did autocratic leadership, but at other times produced performance that was lower than or merely equal to that under the autocratic style. While a democratic leadership style seemed to make subordinates more satisfied, it did not always lead to higher, or even equal, performance.

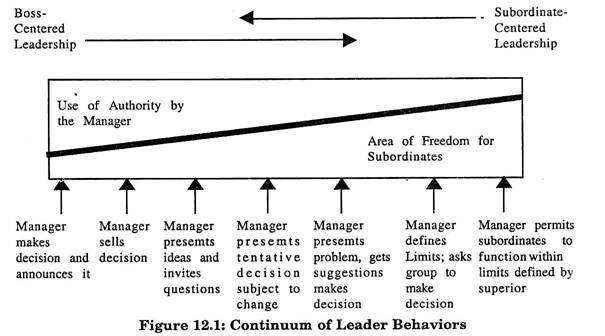

These findings put managers in a dilemma over which style to choose. Moreover, many managers are not used to operating in a democratic mode. To help managers decide which style to choose, particularly when decisions had to be made, management scholars Robert Tannenbaum and Warren H. Schmidt devised a continuum of leader behaviors (see Figure 12.1).

The continuum depicts various gradations of leadership behavior, ranging from the boss-centered approach at the extreme left to the subordinate-centered approach at the extreme right. A move away from the autocratic end of the continuum represents a move towards the democratic end and vice versa.

According to Tannenbaum and Schmidt, while deciding which leader behavior pattern to adopt, a manager should consider forces within themselves (such as their comfort level with the various alternatives), within the situation (such as time pressures), and within subordinates (such as readiness to assume responsibility).

The researchers suggested that in the short run, depending on the situation, the managers should exercise some flexibility in their leader behavior. However, in the long run, the managers should attempt to move towards the subordinate-centered end of the continuum; as such leader behavior has the potential to improve decision quality, teamwork, employee motivation, morale, and employee development.

Further work on leadership at the University of Michigan seemed to confirm that the employee centered approach was much more useful as compared to a job-centered or production-centered approach. In the employee-centered approach, the focus of the leaders was on building effective work groups which were committed to delivering high performance.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

In the job-centered approach, the work was divided into routine tasks and leaders monitored workers closely to ensure that the prescribed methods were followed and productivity standards were met. There were still variations in the level of the output produced.

Sometimes the job-centered approach resulted in the production of a higher output as compared to the employee-centered approach. Therefore, no definite conclusions could be drawn and further studies appeared necessary.

Ohio State Studies:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

In 1945, a group of researchers at Ohio University began extensive investigations on leadership. They initiated the process by identifying a number of important leader behaviors. The researchers then designed a questionnaire to measure the behaviors of different leaders and track factors such as group performance and satisfaction to see which behaviors were most effective.

The most publicized aspect of the studies was the identification of two dimensions of leadership behavior: ‘initiating structure’ and ‘consideration.’ Initiating structure is the extent to which a leader defines his or her own role and those of subordinates so as to achieve organizational goals.

It is similar to the job-centered leader behavior of the Michigan studies, but includes a broader range of managerial functions such as planning, organizing, and directing. It focuses primarily on task-related issues. Consideration is the degree of mutual trust between leader and his subordinates; how much the leader respects subordinates’ ideas and shows concerns for their feelings.

Consideration is similar to the employee-centered leader behavior of the Michigan studies. It emphasizes people-related issues. A consideration-oriented leader is more likely to be friendly towards subordinates, encourages participation in decision-making, and maintains good two-way communication.

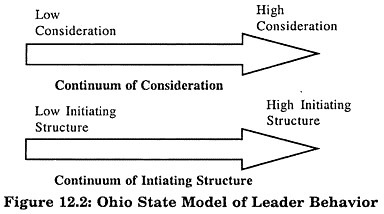

As opposed to the Iowa and Michigan studies, which considered leadership dimensions, i.e. employee-centered approach and job-centered approach, as the two opposite ends of the same continuum, the Ohio State studies considered initiating structure and consideration as two independent behaviors. Therefore, the leadership behaviors operated on separate continuums.

A leader could thus be high on both the dimensions, or high on one dimension and low on the other, or could display gradations in between. This two-dimensional mode of leader’s behavior made sense as many leaders display both initiating structure and consideration dimensions. The Ohio State two-dimensional approach is shown in Figure 12.2.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The two-dimensional approach led to the interesting probability that a leader might be able to place emphasis on both task and people-related issues. They may be able to produce high levels of subordinate satisfaction by being considerate, and at the same time can be specific about the results expected, thereby focusing on task issues too.

However, this theory was too simplistic. It later became apparent that situational factors like the nature of the task and the expectations of subordinates affected the success of leadership behavior.

Likert’s Four Systems of Management:

Professor Rensis Likert and his associates at the University of Michigan studied the patterns and styles of leaders and managers over three decades and developed certain ideas and approaches for understanding leadership behavior.

Likert considers an effective manager as one who is strongly oriented to subordinates and relies on communication to a great extent in order to keep all the departments or individuals working in unison. He suggested four systems of management.

System 1 Management:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

This is also described as an “exploitive-authoritative” style. This represents dictatorial leadership behavior, with all decisions made by the managers, and little employee participation. These managers are highly autocratic, hardly trust subordinates, use negative motivation tactics like fear and punishment, and keep the decision-making powers with them.

System 2 Management:

This management style is called the “benevolent-authoritative” style. Here, managers are patronizing but have confidence and trust in subordinates. They permit upward communication to a certain degree and ask for participation from subordinates. Managers in this system use both rewards and punishment to motivate employees.

They allow subordinates to participate to some extent in decision-making but retain close policy control.

System 3 Management:

System 3 management is referred to as the “consultative” style. Managers in this system do not have complete confidence and trust in subordinates. However, they solicit advice from subordinates while retaining the right to make the final decision.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

This management style involves:

(i) Motivating employees with rewards and occasionally punishment

(ii) Broad policy and general decisions being made at the top while specific decisions are made at lower levels,

(iii) Using both upward and downward communication flow, and

(iv) Managers acting as consultants in order to resolve various problems.

System 4 Management:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

This style of management is called the ‘participative leadership’ style. Managers in this system trust their subordinates completely and have confidence in their abilities. They always ask the opinions of the subordinates and use them constructively.

They encourage participation of employees at all levels in decision-making and use both upward and downward communication. The managers in this system work with their subordinates and other managers as a group. Participation of employees in areas like the setting of objectives and accomplishment of goals is financially rewarded.

Likert found that those managers who adopted the system 4 approaches had the greatest success as leaders, as they were most effective in setting goals and achieving them, and were generally more productive. The research by Likert and his team concluded that high productivity is associated with systems 3 and 4, while systems 1 and 2 are characterized by lower output.

The Managerial Grid:

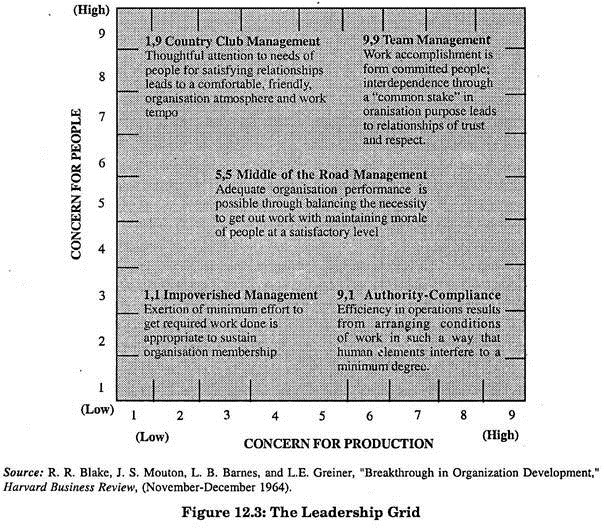

The managerial grid, developed by Robert Blake and Jane Srygley Mouton, is a popular approach for defining leadership styles. Blake and Mouton argue that managerial behavior is a function of two variables: concern for people and concern for production.

They use the managerial grid as a framework to help managers identify their leadership style and to track their movement toward the ideal management style. This grid shown in Figure 12.3 is used all over the world for training managers and for identifying various combinations of leadership styles.

The level of concern for people (employees) is shown on the vertical axis and the level of concern for production on the horizontal axis of the grid. Each axis has a scale ranging from 1 to 9, with the higher numbers indicating greater concern for the specified variable.

Depending on the degree of the managerial concern for people and production, a manager can fall anywhere on the grid.

The management grid reflects five leadership styles:

Leadership style 1, 1 is called ‘impoverished management.’ In this context, there is a low concern for people and low concern for tasks or production. In other words, neither people nor production is emphasized, and little leadership is exhibited. This management style does not provide leadership in a positive sense but believes in a “laissez-faire” approach, relying on previous practice to keep the organization going.

Leadership style 1, 9 is called ‘country club management.’ There is high concern for people but low concern for production. Here managers try to create a work atmosphere in which everyone is relaxed, friendly, and happy. However, no one is bothered about putting in the effort required to accomplish enterprise goals.

This management style may be based on a belief that the most important leadership activity is to secure the voluntary cooperation of group members in order to obtain high levels of productivity. Subordinates of such managers generally report high levels of satisfaction, but the managers may be considered too easy-going and unable to make decisions.

Leadership style 9, 1 which reverses the emphasis of style 1, 9 is called ‘authority-compliance management.’ There is high concern for production but low concern for people in this management style. This management style is task-oriented and stresses the quality of production over the wishes of subordinates.

Such managers may be loyal, conscientious, and personally capable, but may become alienated from their subordinates, who may do only enough work to keep themselves out of trouble.

Leadership style 5, 5 is called ‘organization-man management.’ It is also called ‘middle-of-the- road management.’ Here there is an intermediate (or moderate) amount of concern for both production and people. Managers with this management style believe in compromise, so that decisions are taken but only if endorsed by subordinates.

Such managers may be dependable and may support the status quo, but are not likely to be dynamic leaders. Moreover, they may have difficulty in bringing about innovation and change.

Leadership style 9, 9 is called ‘team management.’ Here there is a high concern for both production as well as employee morale and satisfaction. Team managers believe that concern for people and for tasks are compatible.

They believe that tasks need to be carefully explained and decisions endorsed by subordinates to achieve a high level of commitment. According to Blake and Mouton, 9, 9 orientations is the most desirable one.

The Blake and Mouton managerial grid is widely used as a training device for managers. It is a useful device for identifying and classifying managerial styles, but it does not tell us why a manager falls into one part or another of the grid.

In order to determine the reason, one has to look at underlying causes, such as the personality characteristics of the leader or the followers, the ability of managers, the enterprise environment, and other situational factors that influence how leaders and followers act.

Theory of Leadership # 3. Contingency Theories:

The use of the trait and behavioral approaches to leadership showed that effective leadership depended on many variables, such as organizational culture and the nature of tasks. No one trait was common to all effective leaders. No one style was effective in all situations. Researchers, therefore, began trying to identify those factors in each situation that influenced the effectiveness of a particular leadership style.

They started looking at and studying different situations in the belief that leaders are the products of given situations. A large number of studies have been made on the premise that leadership is strongly affected by the situations in which the leader emerges, and in which he or she operates. Taken together, the theories resulting from this type of study constitute the contingency approach to leadership.

Situational or contingency approaches obviously are of great relevance to managerial theory and practice. They are important for practicing managers, who must consider the situation when they design an environment for performance.

The contingency theories focus on the following factors:

a. Task requirements.

b. Peers’ expectations and behavior.

c. Organizational culture and policies.

There are four popular situational theories of leadership:

(a) Fiedler’s contingency approach to leadership

(b) The path-goal theory,

(c) The Vroom-Yetton model and

(d) Hersey and Blanchard’s situational leadership model. We will discuss each of these briefly.

Fiedler’s Contingency Approach to Leadership:

Fred E. Fiedler provided a starting point for situational leadership research. Fiedler and his associates at the University of Illinois suggested a contingency theory of leadership, which holds that people become leaders not only because of their personality attributes, but also because of various situational factors and the interactions between leaders and followers.

Fiedler’s basic assumption is that it is quite difficult for managers to alter the management styles that made them successful. In fact, Fiedler believes that most managers are not very flexible, and trying to change a manager’s style to fit unpredictable or fluctuating situations is ineffective or useless.

Since styles are relatively inflexible, and since no one style is appropriate for every situation, effective group performance can be achieved only by matching the style of the manager to the situation or by changing the situation to fit the manager’s style. On the basis of his studies, Feidler identified three critical dimensions of the leadership situation that would help in deciding the most effective style of leadership.

Position Power:

This is the degree to which the power of a position enables a leader to get group members to obey instructions. In the case of managers, this is the power derived from the authority granted by the organizational position. According to Fiedler, a leader who has considerable position power can obtain followers more easily than one who lacks this power.

Task Structure:

This refers to the degree to which tasks can be clearly spelled out and people be held responsible for them. When task structure is clear, it becomes easier to assess the quality of performance of the employees, and their responsibility with respect to accomplishment of the task can be precisely defined.

Leader-Member Relations:

This refers to the extent to which group members believe in a leader and are willing to comply with his instructions. According to Fiedler, the quality of leader-member relations is the most important dimension from a leader’s point of view, since the leader may not have enough control over the position power and task structure dimensions.

Fiedler identified two major styles of leadership:

(a) Task-oriented (the leader gives importance to the tasks being performed),

(b) Employee-centered (the leader gives importance to maintaining good interpersonal relations and gaining popularity).

In order to determine whether a leader is task-oriented or employee-centered and to measure leadership styles, Fiedler employed an innovative testing technique.

His findings were based on two sources:

(a) Scores on the least preferred co-worker (LPC) scale – these are ratings made by group members to indicate those persons with whom they would least like to work with; and

(b) Scores on the assumed similarity between opposites (ASO) scale – ratings based on the degree to which leaders identify group members as being like themselves. This scale is based on the assumption that people work best with those with whom they can relate. Even today the LPC scale is used in leadership research.

On the basis of LPC measures, Fiedler found that the leaders who rated their co-workers favorably were those who found satisfaction from maintaining good interpersonal relationships. On the other hand, leaders who rated their co-workers negatively were inclined to be task-oriented.

Fiedler’s model suggests that an appropriate match of the leader’s style (as measured by the LPC score) with the situation (as determined by the three dimensions – position power, task structure, leader-member relations) leads to effective managerial performance.

For instance, a situation characterised by lack of adequate position power of a leader, unclear definition of the task structure and absence of cordial leader-member relationships would favor a task-oriented leader.

At the other extreme, even in a favorable situation wherein the leader has considerable position power, a well-defined task structure and good leader-member relations exist; Fiedler found that a task-oriented leader would be the most effective. Therefore, Fieldler concluded that an employee- oriented leader would be the most effective in moderate situations or situations which fall between these two extremes.

Path-goal Theory:

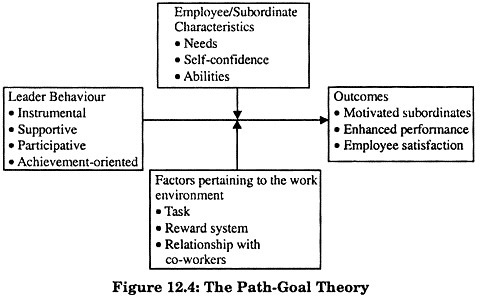

This theory was developed largely by Robert J. House and Terence R. Mitchell. The path-goal theory of leadership attempts to explain how a leader can help his subordinates to accomplish the goals of the organization by indicating the best path and removing obstacles to the goals.

The path-goal theory indicates that effective leadership is dependent on, firstly, clearly defining, for subordinates, the paths to goal attainment; and, secondly, the degree to which the leader is able to improve the chances that the subordinates will achieve their goals. In other words, the path- goal theory suggests that the leaders should set clear and specific goals for subordinates.

They should help the subordinates find the best way of doing things and remove the impediments that hinder them from realizing the set goals.

Expectancy theory is the foundation of the path-goal concept of leadership. Expectancy theory indicates that employee motivation is dependent on those aspects of the leader’s behavior that influence the employee’s goal-directed performance and the relative attractiveness to the employee of the goals involved.

The theory holds that an individual is motivated by his perception of the possibility of achieving a goal through effective job performance. However, the individual must be able to link his or her efforts to the effectiveness of his/her job performance, leading to the accomplishment of goals.

The expectancy theory comprises three main elements:

(a) Effort-performance expectancy (the probability that efforts of the employees will lead to the required performance level),

(b) Performance- outcome expectancy (the probability that successful performance by subordinates will lead to certain outcomes or rewards), and

(c) Valence (the perception regarding the outcomes or rewards). The path-goal theory uses the expectancy theory of motivation to determine ways for a leader to make the achievement of work goals easier or more attractive.

The path-goal theory suggests that four leadership styles (behaviors) can be used in order to affect subordinates’ perceptions of paths and goals.

i. Instrumental Leadership:

Instrumental Leadership behavior involves providing clear guidelines to subordinates. The leaders describe the work methods, develop work schedules, identify standards for evaluating performance, and indicate the basis for outcomes or rewards. It corresponds to task-centered leadership, as described in some of the earlier models.

ii. Supportive Leadership:

Supportive Leadership behavior involves creating a pleasant organizational climate. It also entails the leaders showing concern for the subordinates and their being friendly and approachable. It is a similar concept to relationship-oriented behavior or consideration, in earlier theories.

iii. Participative Leadership:

Participative Leadership behavior entails participation of subordinates in decision-making and encouraging suggestions from their end. It can result in increased motivation.

iv. Achievement-oriented Leadership:

Achievement-oriented Leadership behavior involves setting formidable goals in order to help the subordinates perform to their best possible levels. Here, leaders have a high degree of confidence in subordinates.

The path-goal theory, unlike Fiedler’s theory, suggests that these four styles are used by the same leader in different situations.

Apart from the expectancy theory variables, the other situational factors contributing to effective leadership include:

(a) Characteristics of subordinates, such as their needs, self-confidence, and abilities; and

(b) The work environment, including such components as the task, the reward system, and the relationship with co-workers (see Figure 12.4).

Two general propositions have emerged from the path-goal theory of House and Mitchell:

(i) The behavior of the leader is acceptable and satisfying to subordinates to the extent that the subordinates see such behavior as either an immediate source of satisfaction, or as instrumental to future satisfaction,

(ii) The behavior of the leader will be motivational to the extent that:

(a) Such behavior makes the satisfaction of subordinates’ needs contingent on effective performance, and

(b) Such behavior complements the environment of the subordinates by providing the training, guidance, support, and rewards or incentives necessary for effective performance.

The path-goal theory makes a great deal of sense to the practicing manager. However, this model needs further testing before the approach can be used as a definitive guide for managerial action.

Vroom-Yetton Model:

Another important issue in the study of leadership is the degree of participation of subordinates in the decision-making process. Two researchers, Victor Vroom and Philip Yetton, developed a model of situational leadership to help managers to decide when and to what extent they should involve employees in solving a particular problem.

The Yroom-Yetton model identifies five styles of leadership based on the degree to which subordinates participate in the decision-making process. The five leadership styles are as follows:

Autocratic I (AI):

Managers solve the problem or make the decision themselves, using information available at that time.

Autocratic II (All):

Managers obtain the necessary information from subordinates, then make the decision themselves.

Consultative I (CI):

Managers discuss the problem with relevant subordinates individually, getting their ideas and suggestions without bringing them together as a group. Then the managers make the decision, which may or may not reflect subordinates’ influence.

Consultative II (CII):

Managers share the problem with subordinates as a group, collectively obtaining their ideas and suggestions. Then they make the decision, which may or may not reflect subordinates’ influence.

Group II (GII):

Managers share a problem with subordinates as a group. Managers and subordinates together generate and analyze alternatives and attempt to reach a consensus on the solution. Managers do not try to get the group to adopt the managers’ own preferred solution; they accept and implement any solution that has the support of the entire group.

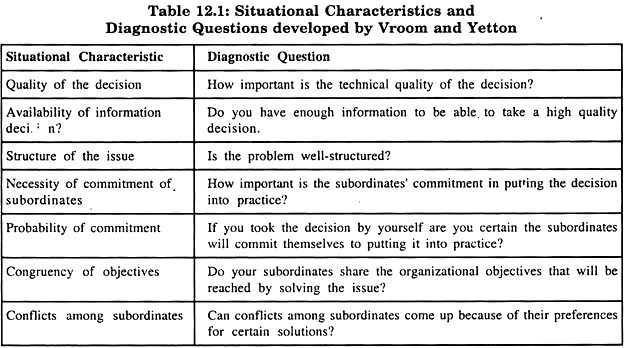

Vroom and Yetton prepared a list of seven ‘yes-no’ questions that managers can ask themselves to determine which leadership style to use for the particular problem they are facing (see Table 12.1).

Vroom and Yetton developed a decision model by matching the decision styles to the situation according to the answers given to the seven questions. The managers can identify the most suitable leadership style for each type of problem by answering these questions.

Depending on the nature of the problem, more than one leadership style might be suitable. Research conducted by Vroom and other management scholars has demonstrated that decisions consistent with the model have been successful.

Hersey and Blanchard’s Situational Leadership Model:

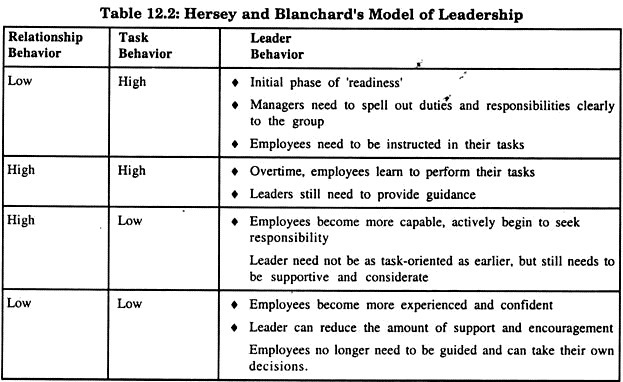

One of the major contingency approaches to leadership is Paul Hersey and Kenneth H. Blanchard’s situational leadership model. It is based on the premise that leaders need to alter their behaviors depending on a major situational factor – the readiness of followers.

Hersey and Blanchard define readiness as the desire for achievement, willingness to accept responsibility and task-related ability, experience and skill. In other words, the readiness of employees refers to their willingness and ability to handle a particular task.

Hersey and Blanchard believe that the relationship between a leader and follower moves through four phases as followers develop over time. Accordingly, leaders need to alter their leadership style (see Table 12.2).

Task behavior refers to the extent to which the leader has to provide guidance to the individual or group. It includes telling people what to do, when to do it, how to do it, and who is to do it.

Relationship behavior refers to the degree to which the leader engages in two-way communication. It includes listening, facilitating and supportive behaviors.

In the initial phase of ‘readiness’, the manager must spell out duties and responsibilities clearly for the group. This is appropriate since employees need to be instructed in their tasks and should be familiarized with the organization’s rules and procedures. It would be inappropriate to use participatory relationship behavior at this stage because the employees need to understand how the organization works.

Over time, as employees learn their tasks, it is still necessary for the leaders to provide guidance, as the new employees are not very familiar with the way the organization functions. However, as the leader becomes acquainted with the employees, he trusts them more. It is at this stage that the leader needs to increase relationship behavior.

In the third phase, employees become more capable and they actively begin to seek greater responsibility. The leader need not be as task-oriented as before, but will still have to be supportive and considerate so that the employees can take on greater responsibilities.

As followers gradually become more experienced and confident, the leader can reduce the amount of support and encouragement. In this fourth phase, followers no longer need direction from their manager and can take their own decisions.

Hersey and Blanchard’s situational leadership model holds that the leadership style should be dynamic and flexible. In order to determine which style combination is more appropriate in a given context, the motivation, experience and ability of followers must be assessed; and re-assessed, as the context changes.

According to Hersey and Blanchard, if the style is appropriate, it will not only motivate employees but will also help them develop in their professions. Therefore, the leader who wants to help his followers to progress, and wants to increase their confidence, should change his style in accordance with their needs.

If managers are flexible in their leadership style, they can be effective in a variety of leadership situations. If, on the other hand, managers are relatively inflexible in leadership style, they will be effective only in those situations that best match their style or that can be adjusted to match their style.

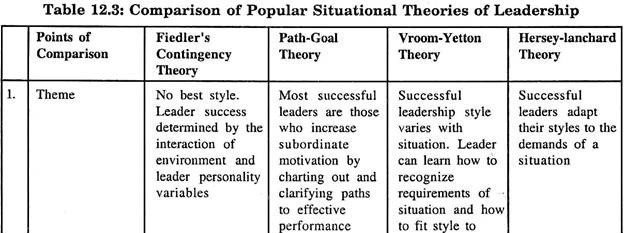

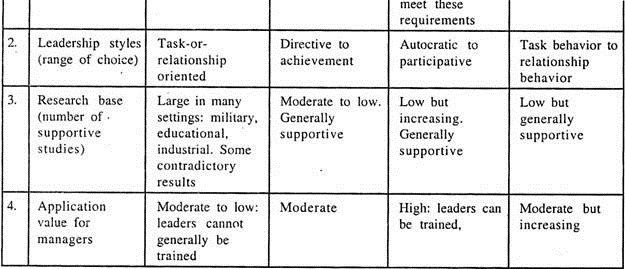

There are a growing number of situational theories of leadership. Each approach adds some insight into a manager’s understanding of leadership. Table 12.3 contains a brief explanation of the four popular leadership theories that stress the importance of situational variables.

Though Fiedler’s theory has the largest research base, since it was formulated earliest, the Vroom-Yetton theory appears to offer the most promise for managerial training.

Theory of Leadership # 4. Transformational Leadership Theory:

Recently, it has been realized that managers are not necessarily leaders. According to one point of view, managers do things right, but it takes leaders to innovate and do the right things. Leaders bring about major changes, and inspire followers to put in extraordinary levels of effort. The German sociologist, Max Weber, introduced the concept of charisma into discussions of leadership.

He regarded charisma as an adaptation of the theological concept of possessing divine grace. Charismatic leaders have great influence over their followers. The followers are attracted to the leader’s magnetic personality, oratory skills, and exceptional ability to respond to crises.

James MacGregor Burns, a pioneer in the study of leadership, discussed the concept of ‘hero’. According to Burns, heroic leadership was displayed by those leaders who inspired and transformed followers.

Leadership expert Bernard M. Bass has extended Burn’s view, characterizing a transformational leader as one who motivates individuals to perform beyond normal expectations by inspiring them to focus on broader missions that transcend their own immediate self-interests, to concentrate on intrinsic higher-level goals (such as achievement and self-actualization) rather than extrinsic lower-level goals (such as safety and security), and to have confidence in their abilities to achieve the extraordinary missions articulated by the leader.

According to Bernard M. Bass, a transformational leader displays the following attributes:

(a) Charismatic leadership,

(b) Individualized consideration and

(c) Intellectual stimulation (offering new ideas to stimulate followers, encouraging followers to look at problems from multiple vantage points, and fostering creative breakthroughs to obstacles that had seemed insurmountable).

The insight provided by Burns and Bass suggest that leaders are able to stimulate, transform, and use the values, beliefs, and needs of their followers to accomplish tasks. Leaders who do this in a rapidly changing or crisis-laden situation are transformational leaders.

The other approaches to leadership such as behavioral or situational approaches typically focus on transactional leadership. Leaders who are accepted by followers as transformational are depicted as more charismatic and intellectually stimulating than leaders described as transactional.

One major distinction between a transactional leader and a transformational leader is that a transactional leader motivates subordinates (followers) to perform at expected levels, whereas a transformational leader motivates individuals to perform beyond normal expectations.

Transformational leadership is not a substitute for transactional leadership. It is a supplementary form of leadership with an add-on-effect performance beyond expectations. The reason for this is that even the most successful transformational leaders require transactional skills as well to effectively manage the day-to-day events that form the basis of a broader mission.

A potential area of concern in discussing and learning more about transformational leadership characteristics is that the discussion and interpretations are beginning to resemble the early trait approaches to leadership theory.

Searching for what constitutes divine grace, attraction and power to influence, is like examining such traits as intelligence, self-confidence and physical attributes, to determine what produces success.