An excusive guide for writing fantastic business letters!

Contents:

- Sequence-of-Ideas Patterns for Writing Business Letters

- Letter about Routine Claims

- Routine Letters about Credit

- Routine Letters about Orders

- Letters about Routine Requests

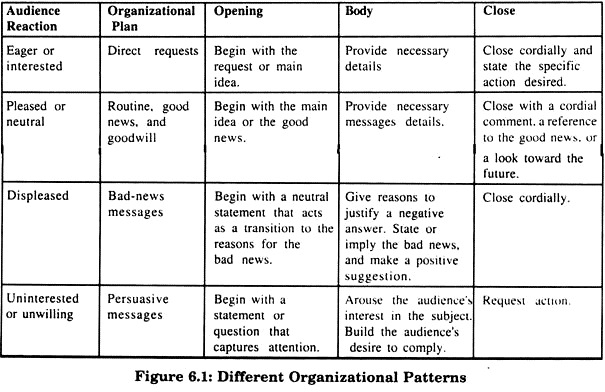

1. Sequence-of-Ideas Patterns for Writing Business Letters:

Letters that convey pleasant messages are referred to as “good news” letters. Letters not likely to generate any emotional reaction are referred to as routine letters. The organizational pattern of both types of letters follows a deductive pattern in which the major idea is presented first, followed by supporting details.

The deductive sequence-of-ideas pattern has several advantages:

The first sentence is easy to write:

a. The first sentence is likely to attract attention. Coming first, the major idea gets the attention it deserves.

b. When good news appears in the beginning, the message immediately puts readers in a pleasant state of mind, rendering them receptive to the details that follow.

c. The arrangement reduces the reading time. Once readers have grasped the important idea, they can move rapidly through the supporting details.

This basic plan is applicable in several business-writing situations:

(i) Routine claim letters and “yes” replies,

(ii) Routine requests related to credit matters and “yes” replies,

(iii) Routine order letters, and “yes”- replies, and

(iv) Routine requests and “yes” replies.

Detailed comments have been made to help you see how principles are applied or violated. Typically, a poorly written and poorly organized example is followed by a well-written and well-organized example. The commentary on poor examples explains why certain techniques should be avoided. And the commentary on well-written examples demonstrates ways to avoid certain mistakes.

The well-written examples are designed to illustrate the application of principles of good writing; they are not intended as models of exact words, phrases, or sentences that should appear in the letters you write. The aim of this case study technique is to enable you to apply the principles you have learned and create your own well-written letters.

2. Letter about Routine Claims:

A claim letter is a request for an adjustment. When writers ask for something to which they think they are entitled (such as a refund, replacement, exchange, or payment for damages), the letter is called a claim letter.

These requests can be divided into two groups:

i. Routine claims and

ii. Persuasive claims.

Routine claims – possibly because of guarantees, warrantees, or other contractual conditions – assume that the request will be granted quickly and willingly, without persuasion. Because it is assumed that routine claims will be granted willingly, a forceful tone is inappropriate.

When the claim is routine (not likely to meet resistance), the following outline is recommended:

a. Request action in the first sentence,

b. Explain the details supporting the request for action.

c. Close with an expression of appreciation for taking the action requested.

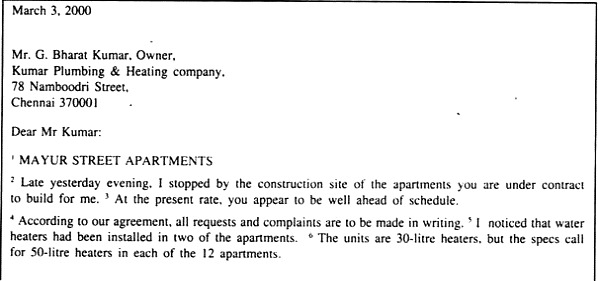

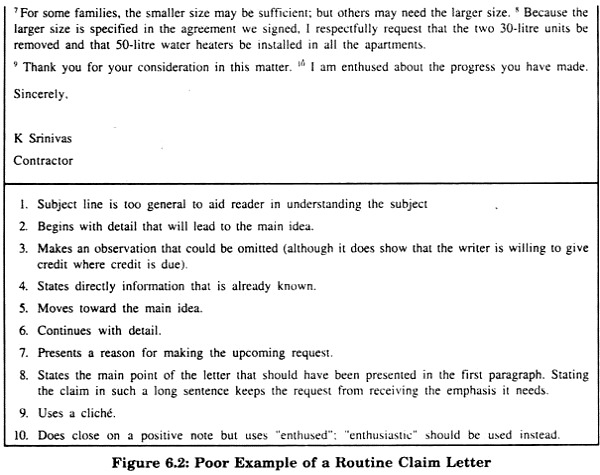

Figure 6.2 illustrates an inductive treatment and figure 6.3 a deductive treatment of a routine claim letter. Written inductively, the letter in figure 6.2 does transmit the essential ideas; but it is unnecessarily long and the main idea is not emphasized.

Surely the builder intended to install 50 litre heaters; otherwise, the building contract would not have been signed. Because a mistake is obvious, the builder would not need to be persuaded. And because compliance can be expected, the claim can be stated without prior explanation.

Without showing anger, suspicion, or disappointment, the claim letter in figure 6.3 asks simply and directly for an adjustment. As a result, the major point receives deserved emphasis. And given the nature of the audience, the response to it should be favorable.

Favorable Response to a Claim Letter. A response to a claim letter is termed an “adjustment” letter. By responding favorably to legitimate requests, businesses can gain a reputation for standing behind their goods and services. A loyal customer may become even more loyal after a business has demonstrated such integrity.

Since the subject of an adjustment letter is related to the goods or services provided, the letter can serve easily and efficiently as a low-pressure sales letter. For example, a letter about a company’s wallpaper might also mention its paint. This type of subtle sales message in an adjustment letter has a better chance of being read than a direct sales letter.

When the response to a claim letter is favorable, present ideas in the following sequence:

Reveal the good news in the first sentence.

a. Explain the circumstances.

b. Close on a pleasant, forward looking note.

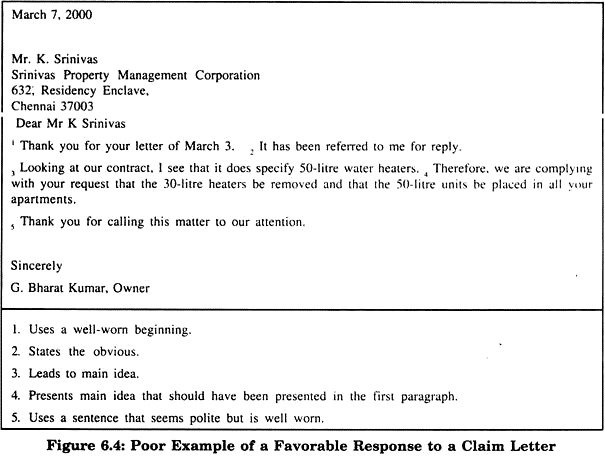

Figure 6.4 illustrates a poorly written inductive response to a claim letter. Read this letter before reading the well written deductive response.

Figure 6.4 does reveal compliance with the request, but the main idea is not emphasized. In the absence of an explanation for the initial installation of 30 litre heaters, the reader could become suspicious of the builder’s intent. Although explaining is not obligatory, an honest and efficient builder would find out what happened. B

y investigating and explaining, the builder may impress the reader as a manager who takes corrective and preventive measures.

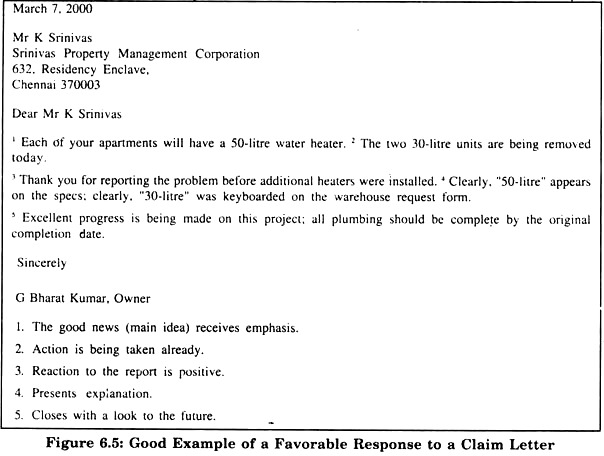

In the revised letter in figure 6.5, notice the deductive treatment and the explanation.

Knowing that the recipient will be happy to learn that the request has been granted, the writer in figure 6.5 simply states it in the first sentence. The details then follow naturally.

3. Routine Letters about Credit:

Normally, credit information is requested and transmitted electronically- or by form letters or simple office forms. When the response to a credit letter is likely to be favorable, the request should be stated at the beginning. Request for information.

The network of credit associations across the world has made knowledge about individual consumers easy to obtain. As a result, exchange of credit information is common in business.

The following is an outline for an effective letter request for credit information about an individual:

a. Identify the request and name the applicant early, preferably in the opening sentence or in the subject line.

b. Assure the reader that the reply will be kept confidential.

c. Detail the information requested. Use a tabulated-form layout to make the reply easy.

d. End courteously. Offer the same assistance to the reader.

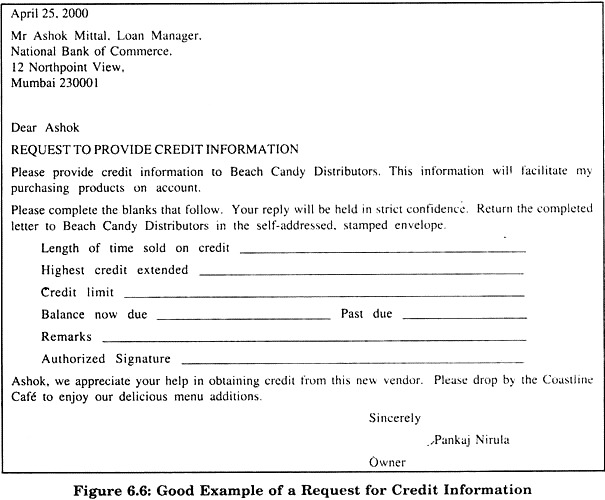

In the letter in figure 6.6, the credit applicant instead of the prospective creditor has written the request for credit information. Notice the subject line in the figure. The subject line serves as the letter’s “title”.

If Beach Candy Distributors (the prospective creditors) had written this letter to the credit reference, an acceptable subject line would be:

Credit Information, Coastline Cafe:

A desirable item of this letter is the use of fill-in items. This enables the recipient to provide the required information with a minimum of effort.

Request for Credit:

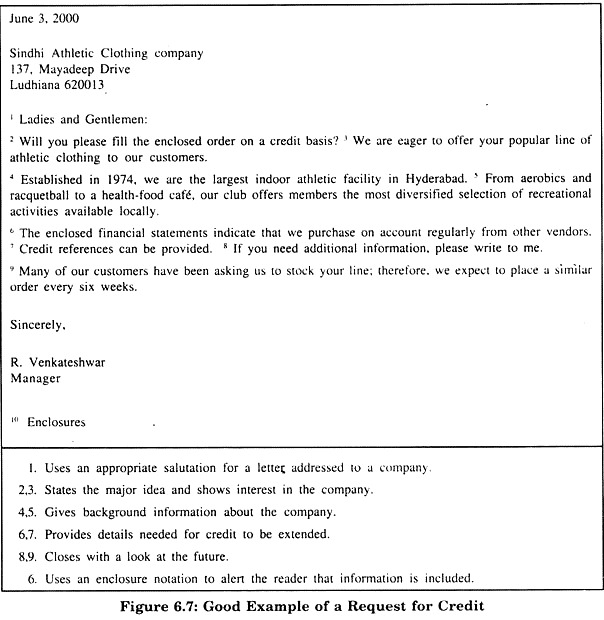

When people want to begin, buying on credit and assume credit will be willingly extended; they can place their request in the first sentence and follow with details. This approach is advisable only when the writer’s supporting financial statements are assumed sufficient to merit a “yes” response. Figure 6.7 illustrates a credit request that follows the deductive plan.

Favorable response to a request for credit. Effective “yes” replies to requests for credit should use the outline shown below:

1. Begin by saying credit terms have been arranged; or if an order has been placed, begin by telling of the shipment of goods, thus implying that credit has been extended.

b. Indicate the foundation upon which the credit extension is based.

c. Present and explain the credit terms.

d. Include some resale or sales-promotional material.

e. End with a confident look toward future business

Why should you discuss the foundation upon which you based your decision to extend credit? To prevent collection problems that may arise later. Indicating that you are extending credit on the basis of an applicant’s prompt paying habits with present creditors encourages continuation of those habits, It recognizes a reputation and challenges the purchaser to live up to it.

When the financial situation become difficult, the purchaser will probably remember the compliment and pay you first.

Why should you discuss the credit terms? To stress their importance and pi event collection problems. Unless customers know exactly when payments are expected, they may not make them on time. And unless they know exactly what the discount terms are, they may take unauthorized discounts.

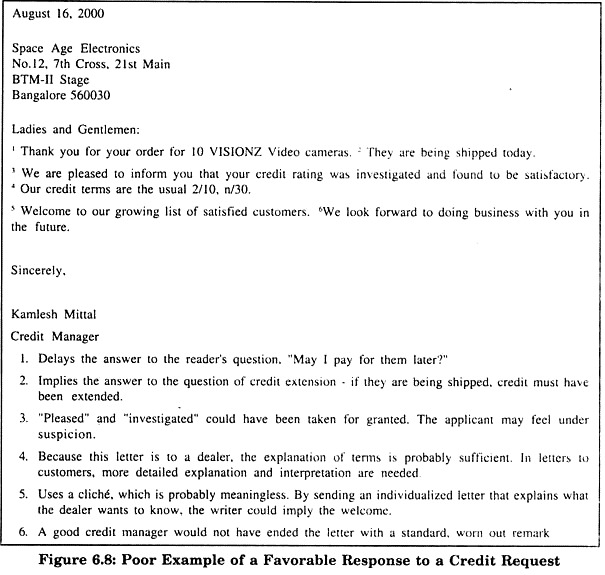

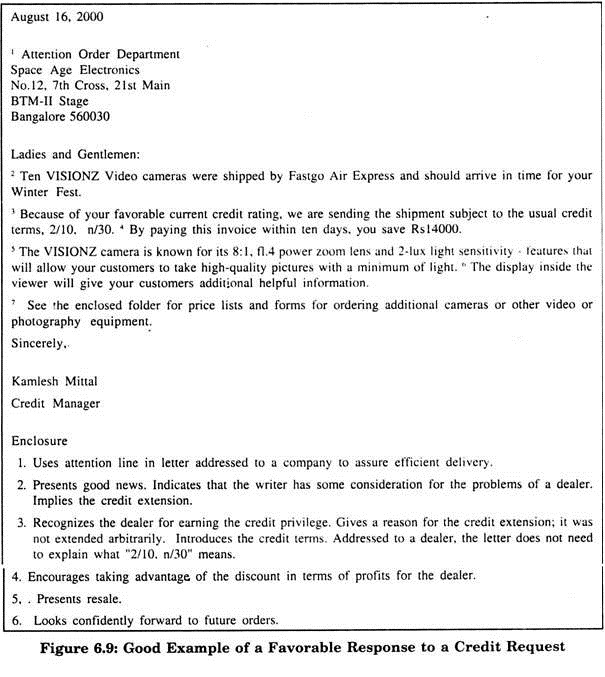

See Figures 6.8 and 6.9 and the commentary that follows to identify the differences between a poorly written and well-written response to a credit request.

Although the letter in figure 6.9 was written to a dealer, the same principles apply when writing to a consumer. Each one – dealers and consumers – should be addressed in terms of individual interests. Dealers are concerned about mark up, marketability, and display; consumers are concerned about price, appearance, and durability. Consumers may require a more detailed explanation of credit terms.

The letter in figure 6.9 performed a dual function: it said “yes” to an application for credit and “yes, we are filling your order.” Because of its importance, the credit aspect was emphasized more than the order. In other cases (if the order is for cash or if the credit terms are already understood), the primary purpose of writing may be to acknowledge an order.

4. Routine Letters about Orders:

Like routine letters about credit, routine letters about orders put the main idea in the first sentence. Details are usually tabulated, especially when more than one item is ordered.

Order Letter:

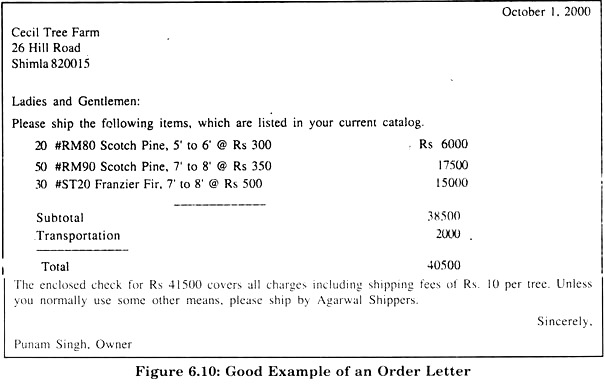

These letters constitute the offer portion of a contract that is fulfilled when the shipper sends the goods (the acceptance part of the contract). So if you want to receive shipment, you should make your order letter a definite order. The outline for order letters is deductive:

a. In the first sentence say “please ship,” “please send,” “I order,” or some other similar statement that assures the seller of the desire to buy, Avoid indefinite statements like “I’m interested,” or “I’d like to.”

b. List the items ordered and give precise details. Be specific by mentioning catalog numbers, prices, colors, sizes and all other information that will enable the seller to fill the order promptly and without the need for further correspondence.

c. Include a payment plan and shipping instructions. Remember that the shipper is free to ship by the normal method in the absence of specific instructions from the buyer. Tell when, where, and how the order is to be shipped.

Close the letter with a confident expectation of delivery.

In large companies, the normal procedure is to use purchase-order forms for ordering. The most important thing you can do as a customer is to make sure your order letter or form is complete and covers all the necessary details. In addition to the application of the outline principles, note the clarity of the physical layout in the order letter in figure 6.6.

Favorable Response to an Order Letter. When customers place an order for merchandise, they expect to get exactly what they ordered as quickly as possible. Most orders can be acknowledged by shipping the order; no letter is necessary. But for initial orders and for orders that cannot be filled quickly and precisely, companies send letters of acknowledgment.

Since, it is not cost effective to send individualized letters of acknowledgment, companies typically send a copy of the sales order Although this method is impersonal, customers appreciate the company’s acknowledging the order and giving them an idea of when the order will arrive.

Non-routine acknowledgments require individualized letters. Although initial orders can be acknowledged through form letters, the letters are more effective if written individually. If they are well written, these letters will not only acknowledge the order but also create customer goodwill and encourage the customer to place additional orders.

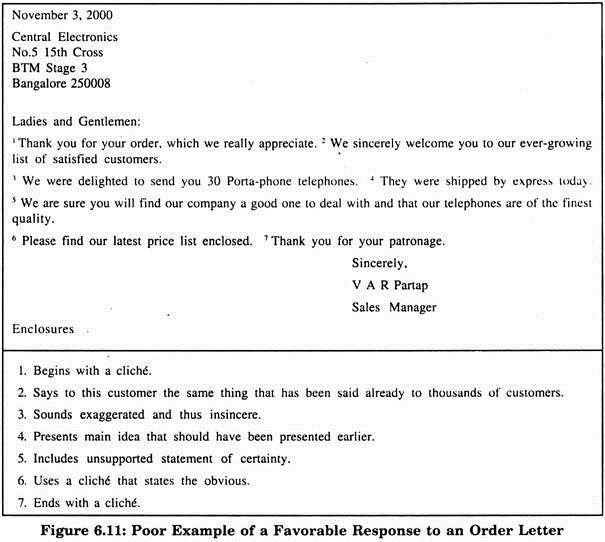

Most people who write letters have no difficulty saying “yes”; but because saying “yes” is easy, they may develop the habit of making their letters sound too artificial.

Take a look at the letter in figure 6.11. Is this letter good enough to create customer goodwill or generate future orders?

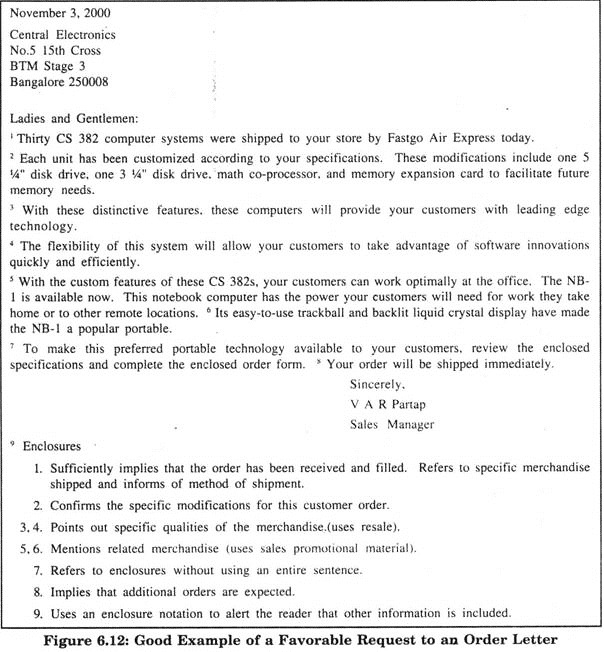

Now let’s look at figure 6.12 to see how the same letter sounds when it confirms shipment of goods in the first sentence, includes concrete resale on the product and business establishment, and eliminates business jargon.

A major purpose of the acknowledgment letter is to encourage future orders. An effective approach for achieving this goal is stating that the merchandise was sent, including resale, and implying that future orders will be handled in the same manner.

Future business cannot be encouraged by merely filling the letter with words like “welcome” and “gratitude” they are overused words. Appropriate action, instead, implies both gratitude and welcome. This is not to say that words of appreciation should not be used; they can be used, but they should sound sincere and original.

5. Letters about Routine Requests:

Notice how routine requests and favorable responses to them use the same organizational pattern. Compared with persuasive requests, routine requests are shorter.

Routine Requests:

Businesspeople often write letters requesting information about people, prices, products and services. Because the request is a door opener for future business, readers accept it optimistically. At the same time, they arrive at an opinion about the writer based on the quality of the letter. The following outline can serve as a guide for preparing effective letters of request

a. Make the major request in the first sentence.

b. Follow the major request with the details that will make the request clear. If possible, use tabulation for added emphasis.

c. Close with a forward look at the reader’s next step.

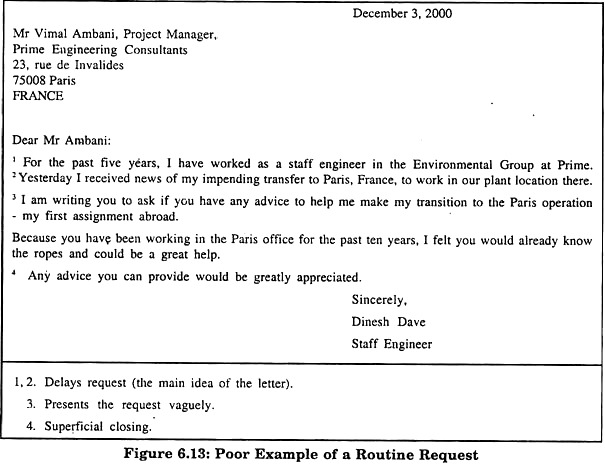

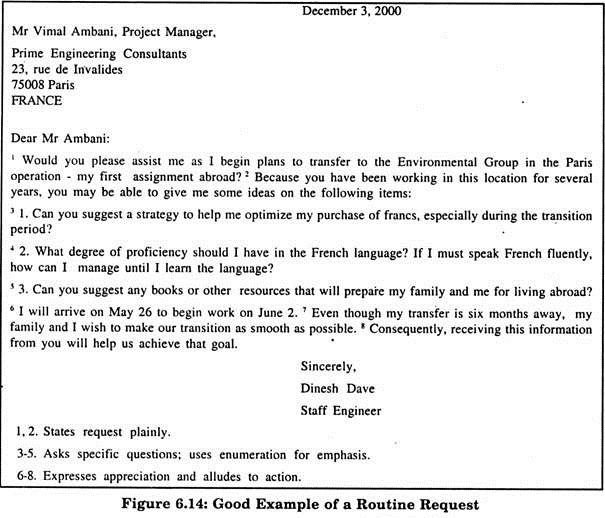

Figure 6.13 is a vague request letter. The same request is handled more efficiently in figure 6.14. In the letter in figure 6.14 – the good example – the writer starts with a direct request for specific information. The request is followed by as much detail as is necessary to enable the reader to answer specifically. It ends confidently, showing appreciation for the action requested.

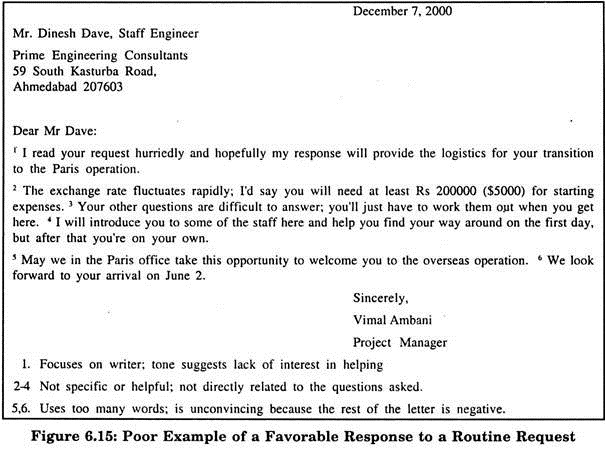

Favorable Response to a Routine Request. Many people say “yes” thoughtlessly. The letter in figure 6.15 grants a request, but it reports the decision in an uninterested manner. With a little planning and consideration for the reader, the letter could have been written as illustrated in figure 6.16.

The principles of writing that apply to business letters also apply to all forms of communication. To make their business messages effective, writers must understand their audience and express their central idea clearly and in a way that is palatable to the audience. In other words, effective writing is “reader-oriented” writing. Reader orientation leads to powerful, well organized, clearly expressed and focused messages.