Contents:

- Writing For the Reader

- Saying “No” to an Adjustment Request

- Saying “No” to a Credit Request

- Saying “No” to an Order for Merchandise

- Saying “No” to a Request for a Favour

- Special Problems in Writing about the Unpleasant

1. Writing For the Reader:

Without empathy for the audience’s feelings, it is hard to gain its cooperation or persuade it to accept tough decisions. So, before composing a letter containing unpleasant news, always ask yourself, “if I were the receiver of the message I am about to transmit, how would I react?”

The answer to that question has an impact on the sequence in which the ideas are presented and the style in which they are expressed.

Sequence of Ideas:

Just as good news is accompanied with details, bad news is accompanied with supporting details (explanation, specific reasons). If the bad news is presented in the first sentence, the reaction is likely to be negative: “That’s unfair” or “This just can’t be”.

After having made such a judgment on the basis of the first sentence, readers are naturally reluctant to change their minds before the last sentence – even though the intervening sentences present valid reasons for doing so. Instead, disappointed readers tend to concentrate on rejecting (and not understanding) supporting details.

From the writer’s point of view, details that support a refusal are very important. If the supporting details are understood and believed by the reader, the message may be readily accepted and a good business relationship preserved. Because the reasons behind the bad news are so important, the writer needs to organize the message in such a way as to emphasize the reasons.

The chances of getting the reader to understand and accept the reasons are much better before the bad news is presented than after the bad news is presented. If the reasons are presented afterwards, the reader may not even read them.

People who are refused wants to know why. To them (and to the writer) the reasons are vital; they must be transmitted and received in a way that satisfies the reader and fulfills the writer’s purpose in communicating the message.

The inductive sequence-of-ideas pattern used in unpleasant messages is as follows:

a. Begin with a neutral idea that leads to the reason for the refusal.

b. Present the facts, analysis, and reasons for the refusal.

c. State the refusal using a positive tone and de-emphasizing techniques.

d. Close with an idea that moves away from the refusal.

Before reading these letters, let us consider the reasoning behind each step in the organization of unpleasant messages.

Step 1: Introductory Paragraph:

The first paragraph in a good-news letter contains the good news, but the introductory paragraph in the bad-news or refusal letter has a different function. It should:

(i) Let the reader know what the letter is about (without stating the obvious) and

(ii) Serve as a transition into the discussion of reasons (without revealing the bad news or leading the reader to expect good news). If these objectives can be accomplished in one sentence, that sentence can be the first paragraph.

Step 2: Facts, Analysis, and Reasons:

Explanations for the refusal have to appear fair and realistic to the reader. And to persuade the reader to accept them, they have to precede the bad-news. Compared with explanations that follow bad-news, those that precede have a better chance of being received with an open mind.

By the time a reader has finished reading this portion of the message, the upcoming statement of refusal may be foreseen and accepted as valid.

Step 3: Refusal Statement:

If the preceding statements are expressed tactfully and appear valid to the reader, the sentence that states the bad news may arouse little or no resentment. In strictly inductive writing, the refusal statement would be placed at the end of the letter.

However, placing a statement of refusal in the last sentence or paragraph would have the effect of placing too much emphasis on it. (Preferably the reasons for the refusal should remain uppermost in the reader’s mind.) So a refusal statement should not be placed at the end of the letter; in addition, it should not be placed in a paragraph by itself since this arrangement would place too much emphasis on it.

Step 4: Closing Paragraph:

A closing paragraph that is about some aspect of the topic other than the bad news itself helps in several ways. It assists in:

(i) De-emphasizing the unpleasant part of the message,

(ii) Conveying some useful information that should logically follow bad news,

(iii) Showing that the writer has a positive attitude, and

(iv) Adding a unifying quality to the message.

Although the preceding outline has four points, a bad-news letter may or may not have four paragraphs. More than one paragraph may be necessary for conveying reasons. In fact, letters that begin with one-sentence paragraphs look more inviting to read. The sequence of these paragraphs, as well as the manner of expression, is strongly influenced by empathy for the recipient of the message.

Style of Expression:

Three stylistic qualities of bad-news messages merit special attention: emphasis/de-emphasis, positive language, and implication. To maintain good human relations, it is vital to emphasize the positive and de-emphasize the negative. The outline recommended for bad-news messages puts the statement of bad news in a subordinate position.

In the same way, stylistic techniques work toward the same goal – subordinating bad news by placing it in the dependent clause, using passive voice, expressing in general terms (where possible and necessary), and using abstract nouns or things (instead of the person written to) as the subject of a sentence.

Although a refusal (bad news) needs to be clear, subordination of it allows the reasoning to get deserved emphasis. Positive language accents the good instead of the bad, the pleasant instead of the unpleasant, what can be done instead of what can’t be done.

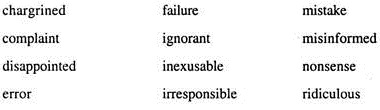

Compared with a negative idea presented in negative terms, a negative idea presented in positive terms is more likely to be accepted. When you are tempted to use the following terms, search instead for words or ideas that sound more positive.

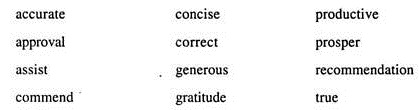

The words in the preceding list evoke feelings that contrast sharply with the positive feelings evoked by words such as:

To increase the number of pleasant sounding words in your writing, practice thinking positively. Strive to see the good in all the difficult business situations you could be in. Implication is often an effective way of transmitting an unpleasant idea.

For example, during the lunch hour one employee says to another, “Will you go with me to Midways? We can watch the cricket match on their TV.” The answer “No, I won’t” communicates a negative response, but it seems unnecessarily direct and harsh.

The same message can be indirectly implied:

“I wish I could.”

“I must get my work done.”

“If I watched cricket this afternoon, I’d be transferred tomorrow.”

By implying the “no” answer, the foregoing responses use positive language; convey reasons or at least a positive attitude; and seem more respectful. These implication techniques – as well as emphasis/de-emphasis, positive language, and inductive sequence – are illustrated in the letters that follow

2. Saying “No” to an Adjustment Request:

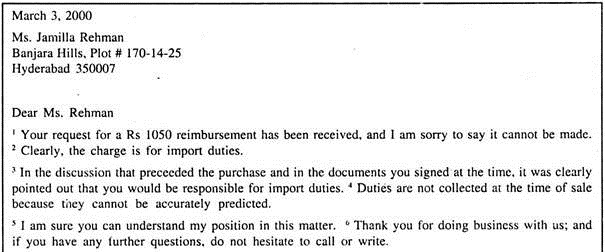

Assume a seller of oriental furniture receives the following request for reimbursement.

Please reimburse me for the amount of the attached bill.

When I ordered my oriental chest (which was delivered yesterday), I paid in full for the price of the chest and the transportation charges. Yet, before the transportation firm would make delivery, I was required to pay Rs. 1050. Recalling that our state does not collect sales tax on foreign purchases, and holding a purchase ticket (sh – 311) marked “paid in full,” I assumed an error that you would be glad to correct.

The Rs. 1050 was a federal tax (import duties). Before placing the order, the purchaser had been told that purchasers were responsible for import duties that would be collected at the time of delivery. In addition, a statement to that effect was written in bold print on the buy-sell agreement of which she was given a copy.

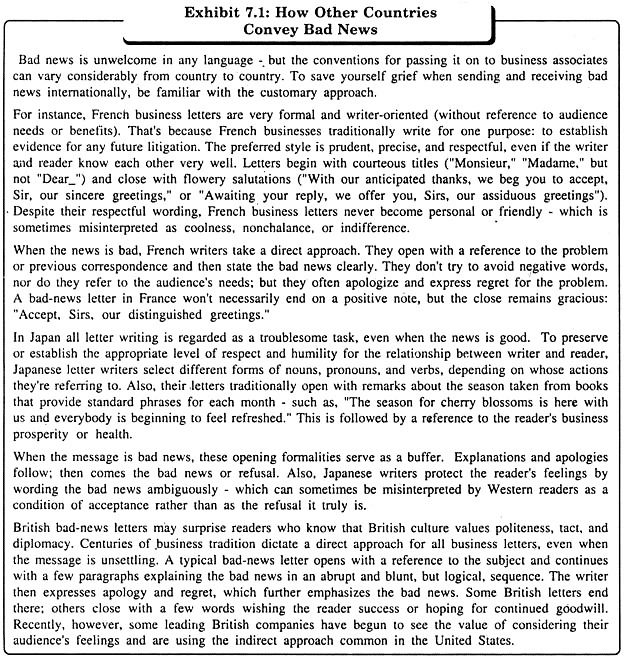

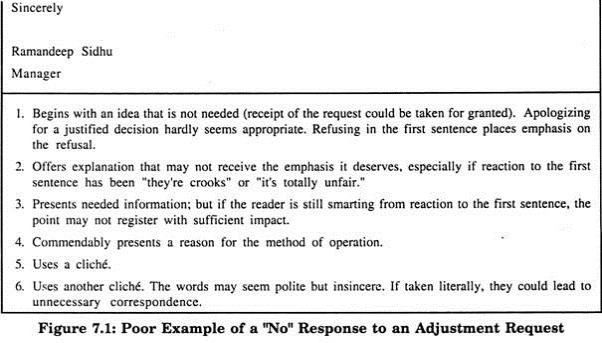

Even though the purchaser is clearly at fault, the seller’s response could be more tactful than the one illustrated in Figure 11.1.

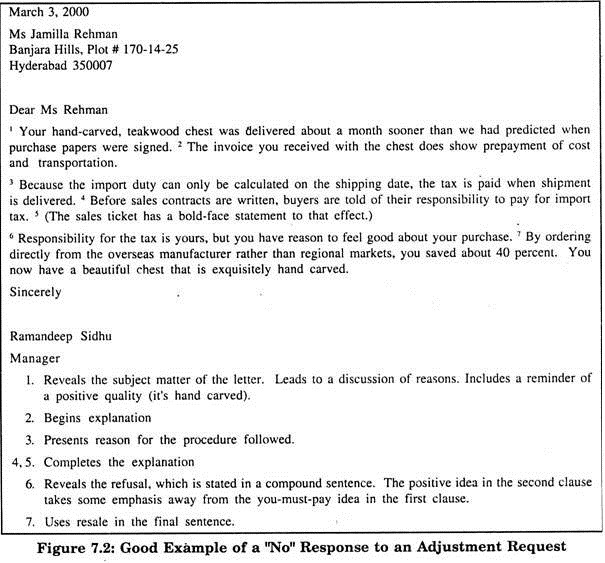

In the revised letter in figure 11.2, observe that the first letter reveals the subject matter of the letter and leads into a presentation of reasons. Reasons precede the refusal, the statement of refusal is subordinated, and the final statement is about something other than the refusal.

As discussed earlier, adjustment letters that say “no” follow a general sequence of ideas:

(i) Begin with a neutral or factual sentence that leads to the reasons behind the “no” answer,

(ii) Present the reasons and explanations,

(iii) Present the refusal in an un-emphatic manner, and

(iv) Close with an off-the-subject thought.

The ending should of course be related to the letter or to the business relationship; but it should not be specific about the refusal. Although the same pattern is followed in credit, order and favor refusals, those letters are sufficiently different to make a discussion of each helpful.

3. Saying “No” to a Credit Request:

Once we have evaluated a request for credit and have decided to say “no” our primary writing problem is to say “no” so tactfully that we keep the relationship on a cash basis. When requests for credit are accompanied with an order, our credit refusals may serve as acknowledgment letters.

And, of course, every business letter is directly or indirectly a sales letter. Prospective customers will be disappointed when they cannot buy on a credit basis. However, if we keep them interested in our goods and services, they may prefer to buy from us on a cash basis instead of seeking credit privileges elsewhere.

In credit refusals, as in other types of refusals, the major portion of the message should be the explanation. Both writers and readers benefit from the explanation of the reasons behind the refusal. For writers, the explanation helps to establish fair mindedness; it shows that the decision was not arbitrary.

For readers, the explanation not only presents the truth (to which they are entitled), it also has guidance value. From it they learn to adjust their credit habits and as a result qualify for credit purchases later.

Including resale – favorable statements about the product ordered – is helpful for four reasons:

(i) It might cause credit applicants to prefer our brand, and may even make them feel like buying it on a cash basis;

(ii) It suggests that the writer is trying to be helpful;

(iii) It makes the writing easier because negative thoughts are easier to de-emphasize when cushioned with resale material;

(iv) And it can confirm the credit applicant’s judgment in choosing the merchandise, thus making an indirect compliment.

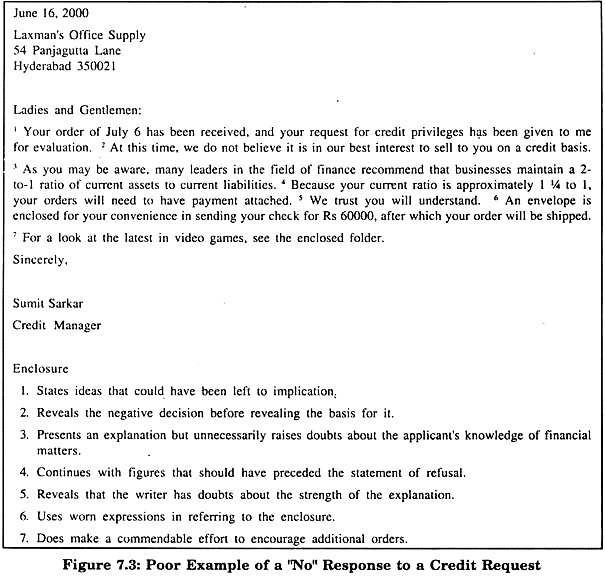

Assume a retailer of electronic devices has placed an initial order and requested credit privileges. After examining the enclosed financial statements, the wholesaler decides the request should be denied. The letter shown in figure 7.3 is inadequate for the purpose. Since you have probably identified the drawbacks in the first paragraph of the letter, read the entire letter before glancing at the commentary.

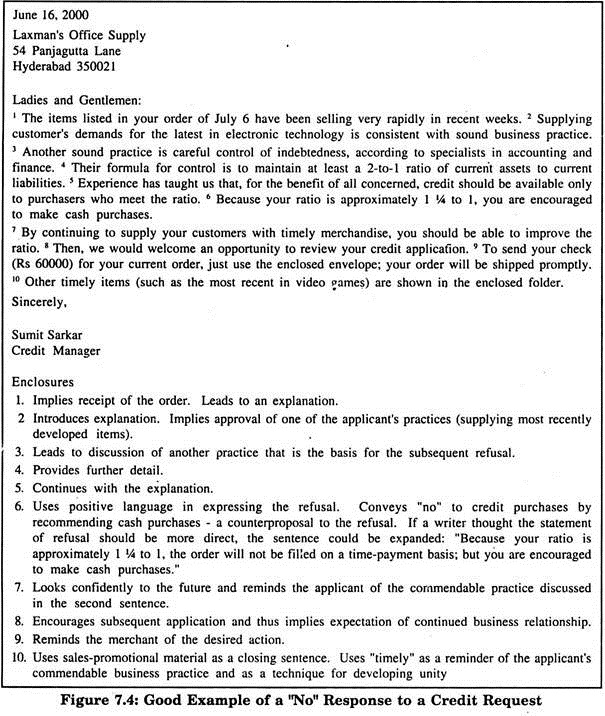

The credit refusal in figure 7.4, in contrast, explains, refuses, and offers to sell for cash. Although credit references have been checked, it says nothing about having conducted a “credit investigation”. It does not identify referents, and it makes no apology for action taken.

4. Saying “No” to an Order for Merchandise:

For several reasons, businesses must sometimes convey bad news concerning orders.

When doing so, writers have three basic goals:

i. To work toward an eventual sale along the lines of the original order.

ii. To keep instructions or additional information as clear as possible.

iii. To maintain an optimistic, confident tone so that the reader won’t lose interest.

Unclear Orders:

When you have received an incomplete or unclear order from a customer, your first job is to get the information needed to complete the order. Make it as simple as possible for the customer to provide the information.

Whether you phone or write for the required data, the indirect approach is usually the best. The first part of your message, the buffer (neutral statement), should confirm the original order; by doing so, it might bolster the sale by referring to desirable features of the product (resale).

Then the source of the confusion could be stated or the problem defined. A friendly, helpful, and positive close should make it simple for the audience to place a corrected order. Take a look at the following letter and the accompanying commentary.

You will be pleased with your order for two dozen Wilson tennis racquets. You’ll find that they sell fast because of their reputation for durability. In fact, tests reveal that they outlast several other more expensive racquets.

[The buffer has a resale emphasis]

Wilson racquets have a standard face, but their patented “Handi-Grip” handles come in several sizes so that players can enjoy the tightest, best fitting grip possible. Handles range in 1/8 inch increments, from 4 ¼ inch (for the average ten year old) to 4 ¾ inch (for an adult male). Please consider your customer mix and decide which sizes will sell best in your store.

[The reason for not immediately filling the order precedes the actual bad news – which is implied – in order to show the positive side of the problem.]

To let us know your preferences, please fill in the enclosed postage-paid card and mail it back today. All sizes are in stock, Mr. Kumar, so your order will be shipped promptly. You can be selling these handsome racquets within a week.

[The close tells how the customer can solve the problem and describes the benefits of acting promptly.]

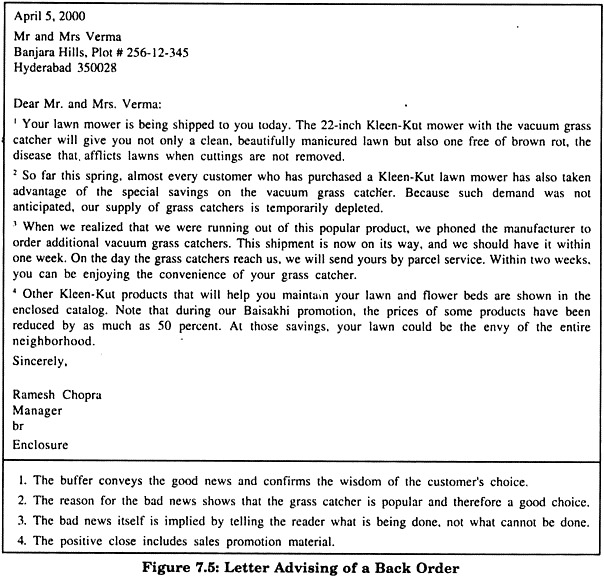

Back Orders:

When you must back order for a customer, you have one or two types of bad news to convey:

(i) You are able to send only part of the order, or

(ii) You are able to send none of the order.

When sending only part of the order, you actually have both good news and bad news. In such situations, the indirect plan works very well. The buffer contains the good news that part of the order is on the way, along with a resale reminder of the product’s attractiveness.

After the buffer come the reasons explaining the delay in shipment of the rest of the order. A strong close encourages a favorable attitude toward the total transaction. For a customer whose order for a lawn mower and its accompanying grass catcher can be only partly filled, your letter might read like the one in Figure 7.5.

Had you been unable to send the customer any portion of this order, you would still have used the indirect approach. However, because you would have no good news to give, your buffer would only have confirmed the sale, and the explanation section would have stated your reason for not filling the order promptly.

Substitutions:

A customer will occasionally request something that you no longer sell or that is no longer produced. If you are sure that the customer will approve a substitute product, you may go ahead and send it. When in doubt, however, first send a letter that “sells” the substitute product and gives the customer simple directions for ordering it.

In either case, avoid calling the second product a substitute because the term carries a negative connotation and detracts from the sales information. Instead, say that you now stock the second product exclusively.

As you can imagine, the challenge is greater when the substitute is more expensive than the original item. So that additional charges seem justified to your customer, show that the more expensive item can do much more than the originally ordered item.

Suppose a customer has ordered a drill that is no longer manufactured. Because of problems with the original drill, the motor has been upgraded. As a result, the price of the drill has increased from Rs. 995 to Rs. 1200. So you write a letter to persuade your audience to buy the more expensive drill:

Tri-Tools, manufacturer of the Mighty-Max drill you ordered, are committed to your satisfaction with every product it makes.

[The buffer includes resale information on the manufacturer.]

For this reason, Tri-Tools conduct extensive testing. Results for the ‘A inch Mighty-Max with the 1/8 horse-power motor show that although it can drill through 2 inches, of wood or ‘A inch of metal, thicker materials put a severe strain on the motor.

Tri-Tools knows that household jobs come in all sizes and shapes, so it now makes a more powerful ¼ inch drill with a 3/8 horsepower motor. The new Mighty-Max drill can cut through materials twice as thick as those the former model could handle.

[The reasons for the bad news are explained in terms of the customer’s needs.]

Even with its superior capabilities, the new Mighty-Max costs only about 20 percent more than the discontinued model. Using this more powerful drill, you can be confident that even heavy-duty jobs will cause no overheating

[The bad news is stated positively. The writer emphasizes the product the firm carries rather than the one it does not.]

You can be using your new heavy-duty drill by next week if you just check the YES box on the enclosed form and mail it in the postage-paid envelope along with a cheque for Rs. 205. Your new, worry free Mighty-Max will be on its way to you at once.

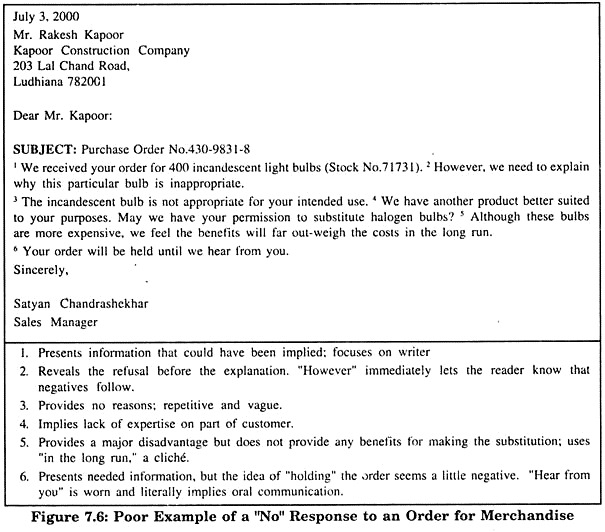

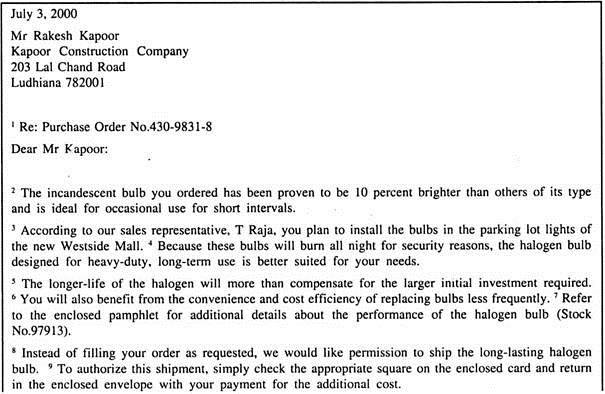

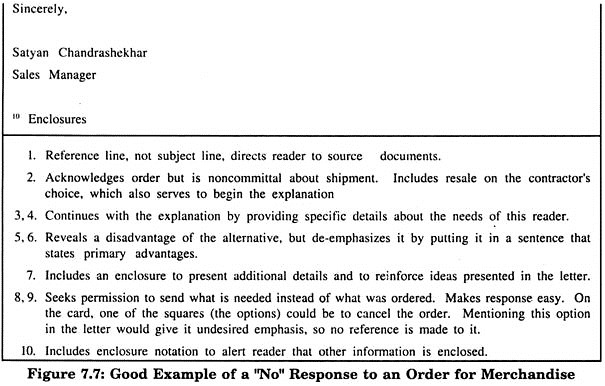

Offering a More Suitable Product:

Sometimes customers order one item when they can more profitably use another. Suppose a contractor has ordered light bulbs that are inappropriate for his needs. Filling the order as submitted would be a mistake, and the customer is likely to be dissatisfied.

Although the form letter in figure 11.6 may get the desired results (convince the recipient that the type of light bulb ordered is not the type needed), the letter in figure 7.7 applies sound writing principles more effectively.

Taking the time required to write such a long letter to a customer may at first seem questionable. But since such circumstances often occur, the letter can be stored in the computer and quickly adapted, whenever necessary, to a similar situation. Moreover, such a letter would be more appealing to the audience than a coldly worded, impersonal form letter.

When people say “no” in a letter, they usually do so because they think “no” is the better answer for all concerned. They can see how recipients will ultimately benefit from the refusal. If the letter is based on a sound decision, and if it has been well written, recipients will probably recognize that the sender did them a favor by saying “no”.

5. Saying “No” to a Request for a Favour:

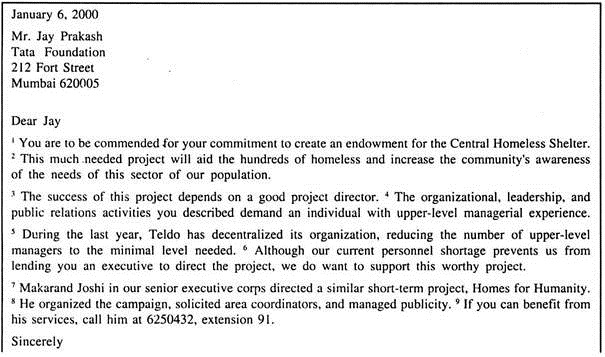

When a request for a favor must be denied, the same reasons before refusal pattern are recommended. To ensure the continuance of positive relationships, the recipient of a request for a favor may offer an alternative to the favor requested, i.e. a counterproposal.

In the letter in Figure 7.8, the writer explains why the company cannot lend an executive to direct a major community effort and recommends a member of the company’s senior executive corps as a counterproposal.

6. Special Problems in Writing about the Unpleasant:

While studying the preceding pages, you may have thought about the following questions:

i. Is an inductive outline appropriate for all letters that convey bad news? It is, for almost all. Normally, the writer’s purpose is to convey a clear message and retain recipient’s goodwill. In the rare circumstances in which a choice must be made between the two, clarity is the better choice.

When the deductive approach will serve a writer’s purpose better, it should be used. For example, if you submit a clear and tactful refusal and the receiver resubmits the request, a deductive presentation may be justified in the second refusal.

Placing a refusal in the first sentence can be justified when:

(a) The letter is the second response to a repeated request.

(b) A very small, insignificant matter is involved.

(c) A request is obviously ridiculous, immoral, unethical, illegal or dangerous.

(d) The writer’s intent is to shake the reader.

(e) The writer-reader relationship is so close and longstanding that satisfactory human relations can be taken for granted.

(f) The writer wants to demonstrate authority.

In most writing situations, the preceding circumstances do not exist. When they do, a writer’s goals may be accomplished by stating the bad news in the first sentence.

ii. Don’t readers become impatient when a letter is inductive, and won’t that impatience interfere with their understanding of the reasons? Concise, well-written explanations are not likely to make readers impatient.

They relate to the reader’s problem, present information not already known, and help the reader understand. Even if readers do become impatient while reading a well-written explanation, that impatience is less damaging to understanding than would be the anger or annoyance that often results from encountering bad news in the first sentence.

Let us now examine the difficulties involved and pitfalls to be avoided when writing the introductory paragraph (the buffer), stating the bad news, and composing the closing lines.

First Paragraph:

The introductory paragraph should let the reader know the topic of the letter without saying the obvious. It should build a transition into the discussion of reasons without revealing the bad news or leading a reader to expect good news. In other words, it should be a neutral, relevant, succinct lead-in to the bad news. And, above all, it should not be misleading.

Here are some other things to avoid when writing a buffer:

Avoid saying “no”. An audience encountering the unpleasant news right at the beginning will react negatively to the rest of the message, no matter how reasonable and well phrased it is.

Avoid using a know-it-all tone. When you use phrases such as “you should be aware that,” the audience will expect your lecture to lead to a negative response and will, as a result, become resistant to your message.

Avoid wordy and irrelevant phrases and sentences. Sentences such as “we have received your letter,” “this letter is in reply to your request,” and “we are writing in response to your request” are irrelevant. You can make better use of space by referring directly to the subject of the letter.

Avoid apologizing. An apology weakens your explanation of the unfavorable decision.

Avoid writing a buffer that is too long. The point is to identify briefly something that both you and the audience are interested in and agree on before proceeding in a businesslike way.

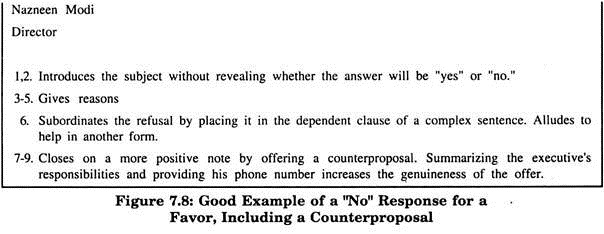

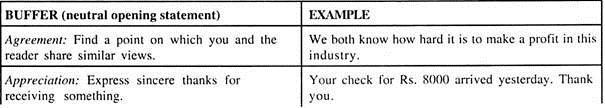

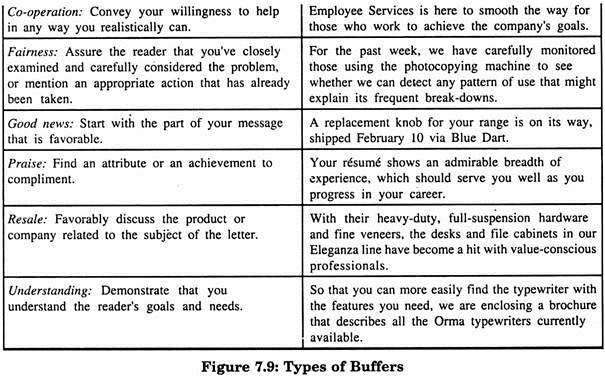

Figure 7.9 shows types of buffers you could use to open a bad-news message tactfully. After you have composed a buffer, evaluate it by asking yourself four questions: is it pleasant? Is it relevant? Is it neutral (saying neither yes nor no)? Does it provide for a smooth transition to the reasons that follow? If you can answer “yes” to every question, you may proceed confidently to the next section of your message.

Bad-News Sentence:

In a sense, a paragraph that presents the reasoning behind a refusal at least partially conveys the refusal before it is stated. Yet, one sentence needs to convey (directly or by implication) the conclusion to which the preceding details have been leading. The most important considerations are positive language and emphasis.

Take a look at the following examples and the accompanying critique:

Your request is therefore being denied.

[Being negative, the idea is not pleasant. Stated in negative terms, the idea is still less pleasant. And the word “denied” stands out vividly because it is the last word.]

We are therefore denying your request.

[The simple sentence structure is emphatic. The active voice makes it emphatic and abrasive.]

The preceding figures do not justify raising your credit limit to Rs. 30,000 as you requested, but they do justify raising the limit to Rs. 15,000.

[The sentence uses negative language, but it does use commendable techniques of subordination: it places the negative in a long, two-clause sentence, and it includes a positive idea in the Sentence that contains the negative idea.]

To soften the impact of a negative idea, a very helpful technique is implication. The following sentences illustrate techniques for implying a refusal.

My department is already shorthanded, so I’ll need all my staff for at least the next two months.

[Bad-news is implied and subordinated in a complex sentence.]

If the price were Rs. 35,000, the contract would have been signed.

[States a condition under which the answer would have been “yes” instead of “no.” Note the use of the subjunctive words “if and “would.”]

By accepting the arrangement, the ABC Company would have tripled its costs.

[States the obviously unacceptable results of complying with the request.]

Last Paragraph:

After having presented valid reasons and a tactful refusal, a writer needs a closing paragraph that includes useful information and demonstrates empathy for the audience.

The purpose of the close is to end the message on a more upbeat note. Follow these guidelines for the last paragraph of a bad-news letter:

i. Don’t refer to or repeat the bad news.

ii. Don’t apologize for the decision or reveal any doubt that the reasons will be accepted (avoid statements such as “I trust our decision is satisfactory”).

iii. Don’t urge additional communication (e.g. “if you have further questions, please write), unless you are really willing to discuss your decision further.

iv. Don’t anticipate problems (avoid statements such as “should you have further problems, please let us know”).

v. Don’t include cliches that are insincere in view of the bad news, (e.g., “if we can be of any help, please contact us”).

vi. Don’t reveal any doubt that you will keep the person as a customer (avoid phrases such as “we hope you will continue to do business with us”).

The final paragraph is usually shorter than the preceding explanatory paragraph. Sometimes a one-sentence closing is enough; in other cases, two or three sentences may be needed. The final sentence should bring a unifying quality to the whole message.

The repetition of a word or reference to some positive idea that appears earlier in the letter serves this well. Avoid restating the refusal or referring to it because that would only serve to emphasize it.

Possibilities for the final sentence include reference to some pleasant aspect of the preceding discussion, resale, sales promotional material, an alternative solution to the reader’s problem, some future aspect of the business relationship, or an expression of willingness to assist in some other way.

Consider the following closures which use the preceding suggestions. In a letter denying request for free repair:

“According to a recent survey, a four-headed VCR produces sound qualities that are far superior to a two-headed VCR; it was an ideal choice.”

The writer uses resale, reminding the reader that his four-headed VCR has a superior feature.

In a letter refusing permission to the reader to interview certain employees on the job, the writer seeks to show a good attitude by offering to do something else:

“If you would like to see the orientation film we show to management trainees, you would be most welcome”.