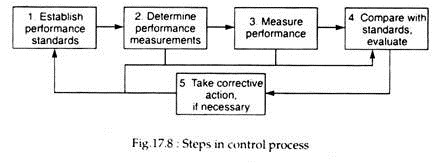

This article throws light upon the five important steps involved in organisational control process. The steps are: 1. Establishing Standards 2. Determining Performance Measurements 3. Measuring Performance 4. Comparing Performance against Standards and Analysing Deviations 5. Taking Corrective Action, if Needed.

Step # 1. Establishing Standards:

The first step in the control process is establishment of standards of performance. A standard is a target against which subsequent performance is to be compared.

We know how important it is for the manager to set objectives that channel the efforts of the entire organisation. In fact, we have discussed in detail goal setting and management by objectives (MBO). A standard is a measuring device, quantitative or qualitative, that is designed to help monitor the performance of people, capital goods or processes.

For the purpose of control a standard is defined as a unit of measurement that can serve as a reference point for evaluating results. Thus, in a broad sense, goals, objectives, quotas, and performance targets will also serve as ‘standard’ in the control process. Some specific standards are-sales quotas, budgets, job deadlines, market share and profit margins.

The exact nature of standards to be used largely depends on what is being monitored. Standards for comparison apply to personnel, marketing, production, financial operations and so on.

To the extent possible, standards established for control purposes should be derived from the organisation’s goals. Like business objectives, they should be expressed in measurable term. On a broader level, control standards reflect organisational strategy.

A final aspect of establishing standards is to decide which performance indicators are relevant. When, for example, a new product is introduced, its manufacturer should have some idea in advance whether the first month’s sales figures will accurately indicate long-term growth or whether sales will take some time to pick up.

Five common types of standards are physical, technical, monetary, managerial and time:

(1) Physical standards might include quantities of products or services, number of customers or clients, or quality of product or service.

(2) Technical standards might include specifying machine tolerances, acceptable levels of quality, items produced per hour on an assembly line and bid specifications developed by the engineering department.

(3) Monetary standards are expressed in rupees and include labour costs, selling costs, material costs, sales revenue, gross profits, and the like.

(4) Managerial standards include such things as reports, regulations and performance evaluation. All these must focus only on the key areas and the kind of performance required to reach specific goals.

(5) Time standards might include the speed with which jobs should be done of the deadlines by which jobs are to be completed.

Qualitative standards also play an important role in the control process, although managers and subordinates are not always aware of these. Examples of non-quantifiable standards are: an appropriate dress on the job, personal hygiene, co-operative attitudes, hiring qualified personnel, promoting the best person, and so on. It is, however, very difficult to achieve control over qualitative standards.

Step # 2. Determining Performance Measurements:

Selling standards hardly serves any purpose unless some steps are taken to measure actual performance. While the first step in the control process establishes standard the second step asks managers and others to measure the performance is in line with the set standards.

In other words, the second step in control is to determine the appropriate measurement of performance progress.

Some relevant questions that crop up at this stage are:

(1) What is the frequency with which performance has to be measured — hourly, daily, weekly, yearly?

(2) What will be the exact form of measurement — a phone call, visual inspection, a written report?

(3) Who has to be involved — the manager, an assistant, a staff department?

Another consideration is that the measurement should not be a complex and expensive exercise. Moreover, measurement has to be made in such a way that it can be easily explained to and understood be employees and others.

Step # 3. Measuring Performance:

The next step in the control process is increasing performance. In this context, performance refers to that which we are attempting to control. The measurement of performance is a constant, ongoing activity for most organisations and for control to be effective, relevant performance measures must be valid.

When a manager is concerned with controlling sales, daily, weekly or monthly sales figures represent actual performance. For a production manager, performance may be expressed in terms of unit cost, quality or volume. For employees, performance may be measured in terms of quality or quantity of output. Valid performance measurement, however difficult to obtain, is necessary to maintain effective control.

Performance itself is measured once the frequency and form of monitoring system are determined.

There are various ways of measuring performance:

(1) Observation,

(2) Reports, both oral and written,

(3) Automatic methods,

(4) Inspections, tests, or samples.

Many U.S. firms ape now using internal auditors who make use of all these methods.

Step # 4. Comparing Performance against Standards and Analysing Deviations:

A critical control step is comparing actual performance with planned performance. Facts about performance above are relatively useful.

So, the fourth step in the control is to compare measured performance against the standards developed in Step 1. Actual performance may be higher, lower or the same as the standard. The key issue here is how much leeway is permissible before remedial action is taken.

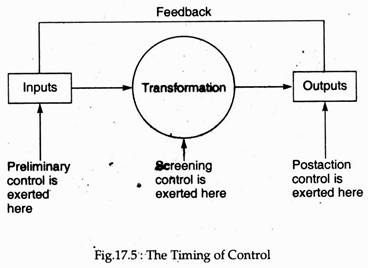

For screening control systems, it is important that comparisons between performance and standards be made frequently. The rationale for using screening control in the first place is to enable managers to correct problems early in the transformation process before errors begin to compound. Hence, sophisticated feedback systems may be necessary to provide promptly the information management needs to make comparisons.

If managers possess clear, simple standards that outline the acceptable and unacceptable, they can apply the standards to specific performances to be able to make a comparison between the ‘what is’ and the ‘what should be’.

If the comparison does not yield results or measurements that are acceptable standards, action may be called for. Measurements have to be taken regularly in order to discover any deviations as quickly as possible.

As an example consider a salesperson who repeatedly fulfills sales quota for a given territory. It could imply superior talent. It could also mean an inaccurate quota: he would fulfill his normal quota in half the time allowed.

Over-achievement may mean under-utilisation of manpower and such inappropriate use can result in lost opportunities for the organisation. So it is first of all necessary to determine the cause of the deviation and take corrective action thereafter.

It is absolutely essential to analyze deviations to determine why the standard is not being met when performance falls short of standard. It is really important decision making to identify the real causes of performance problems rather than just the symptoms. Managers often make use of staff assistance and third parties to aid them in analysing deviations, especially in important matters.

Step # 5. Taking Corrective Action, If Needed:

The final step in the control process is to evaluate performance (via the comparisons made in Step 3) and then take appropriate action. This evaluation draws heavily on a manager’s analytic and diagnostic skills.

After evaluation, one of the three actions is usually appropriate:

Maintain the Status Quo:

One response is to do nothing, or maintain the status quo. This action is generally appropriate when performance more or less measures up to the standard.

Correct the Deviation:

It is more likely that some action will be needed to correct a deviation from the standard. If the cost-reduction standard is 4% and we have thus far managed only a 1% reduction, something must be done to get us back on track. We may need to motivate our employees to work harder or to supply them with new machinery.

Change Standards:

A final response to the outcome of comparing performance to standards is to change the standards. The standard may have been too high or too low to begin with. This is apparent if large number of employees exceeds the standard by a wide margin or if no one ever meets the standard.

In other situations, a standard that was perfectly good when it was set may need to be adjusted because circumstances have changed. A sales increase standard of 10% may have to be modified when a new competitor comes on the scene. Given new market conditions, the old standard of 10% may no longer be realistic.

Now, determining the precise action to be taken will depend on three things: the standard, the accuracy of the measurements that determine that a deviation exists, and the diagnosis of the person or device investigating the cause for the deviation.

It may be noted that there may be various causes of deviations from standards and each will, or may, require a unique solution.

Managers, however, must be allowed some discretion to use their best judgements because most problems they face cannot be adequately proceduralised. No management procedure is a substitute for proper judgement.

One final point may be noted in this context.

As shown in Fig. 17.5, the corrective action may be to alter the planning and control system in any of the following ways:

1. Change the original standard (perhaps it was too low or too high).

2. Change the performance measurements (perhaps inspect more or less frequently or even alter the measurement system itself).

3. Change the manner in which deviations are analysed and interpreted.