In this article we will discuss about Decision Making:- 1. Meaning and Definitions of Decision Making 2. Characteristics of Decision-Making 3. Types 4. Factors Involved 5. Techniques and Methods 6. Process and Steps 7. Elements 8. Principles 9. Approaches 10. Models 11. Importance. Also learn about: 1. Decision Making In Management 2. What Is Decision Making Process 3. Decision Making Types 4. Importance Of Decision Making 5. Decision Making In Business 6. Decision Making Techniques 7. Decision Making Definition By Author

Contents:

- Meaning and Definitions of Decision Making

- Characteristics of Decision-Making

- Types of Decision-Making

- Factors Involved in Decision-Making

- Techniques and Methods of Decision-Making

- Process and Steps of Decision-Making

- Elements of Decision-Making

- Principles of Decision-Making

- Approaches of Decision-Making

- Models of Decision-Making

- Importance of Decision-Making

1. Meaning and Definitions of Decision Making:

One of the most important functions of a manager is to take decisions in the organization. Success or failure of an organization mainly depends upon the quality of decision that the managers take at all levels. Each managerial decision, whether it is concerned with planning, organizing, staffing or directing is concerned with the process of decision-making.

It is because of its perverseness of Decision-Making that professor Herbert Simons has said the process of managing as a process of decision-making. As per his opinion a post of position cannot be said to be managerial until and unless the right of Decision-Making is attached to it.

A decision is a course of action which is consciously chosen from among a set of alternatives to achieve a desired result. It means decision comes in picture when various alternatives are present. Hence, in organization an execute forms a conclusion by developing various course of actions in a given situation. It is a made to achieve goals in the organization. To decide means to cut off on to come to a conclusion.

It is also a mental process. Whether the problem is large or small in the organization, it is usually the manager who has to comfort it and decide what action to take. So, the quality of managers’ decisions is the Yardstick of their effectiveness and value to the organization. This indicates that managers must necessarily develop decision making skills.

According to D. E. McFarland, “A decision is an act of choice – wherein an executive forms a conclusion about what must not be done in a given situation. A decision represents a course of behavior chosen from a number of possible alternatives”.

According to Haynes and Massie, “a decision is a course of action which is consciously chosen for achieving a desired result”.

According to R. A. Killian, “A decision in its simplest form is a selection of alternatives”.

Thus, from above definitions it can be concluded that decision-making is a typical form of planning. It involves choosing the best alternative among various alternatives in order to realize certain objectives. This process consists of four interrelated phases, explorative (searching for decision occasions), speculative (identifying the factors affecting the decision problem), evaluative (analysis and weighing alternative courses of action and selective (choice of the best course of action).

2. Characteristics of Decision-Making:

The important characteristics of decision-making may be listed thus:

1. Goal-Oriented:

Decision-making is a goal-oriented process. Decisions are usually made to achieve some purpose or goal. The intention is to move ‘toward some desired state of affairs’.

2. Alternatives:

A decision should be viewed as ‘a point reached in a stream of action’. It is characterized by two activities – search and choice. The manager searches for opportunities, to arrive at decisions and for alternative solutions, so that action may take place. Choice leads to decision. It is the selection of a course of action needed to solve a problem. When there is no choice of action, no decision is required. The need for decision-making arises only when some uncertainty, as to outcome exists.

3. Analytical-Intellectual:

Decision-making is not a purely intellectual process. It has both the intuitive and deductive logic; it contains conscious and unconscious aspects. Part of it can be learned, but part of it depends upon the personal characteristics of the decision maker. Decision-making cannot be completely quantified; nor is it based mainly on reason or intuition. Many decisions are based on emotions or instincts. Decision implies freedom to the decision maker regarding the final choice; it is uniquely human and is the product of deliberation, evaluation and thought.

4. Dynamic Process:

Decision-making is characterized as a process, rather than as, one static entity. It is a process of using inputs effectively in the solution of selected problems and the creation of outputs that have utility. Moreover, it is a process concerned with ‘identifying worthwhile things to do’ in a dynamic setting. A manager for example, may hire people based on merit regularly and also pick up candidates recommended by an influential party, at times. Depending on the situational requirements, managers take suitable decisions using discretion and judgment.

5. Pervasive Function:

Decision-making permeates all management and covers every part of an enterprise. In fact, whatever a manager does, he does through decision-making only; the end products of a manager’s work are decisions and actions. Decision-making is the substance of a manager’s job.

6. Continuous Activity:

The life of a manager is a perpetual choice making activity. He decides things on a continual and regular basis. It is not a one shot deal.

7. Commitment of Time, Effort and Money:

Decision-making implies commitment of time, effort and money. The commitment may be for short term or long-term depending on the type of decision (e.g., strategic, tactical or operating). Once a decision is made, the organisation moves in a specific direction, in order to achieve the goals.

8. Human and Social Process:

Decision-making is a human and social process involving intellectual abilities, intuition and judgment. The human as well as social imparts of a decision are usually taken into account while making the choice from several alternatives. For example, in a labour-surplus, capital-hungry country like India managers cannot suddenly shut down plants, lop off divisions and extend the golden handshake to thousands of workers, in the face of intense competition.

9. Integral Part of Planning:

As Koontz indicated, ‘decision making is the core of planning’. Both are intellectual processes, demanding discretion and judgment. Both aim at achieving goals. Both are situational in nature. Both involve choice among alternative courses of action. Both are based on forecasts and assumptions about future risk and uncertainty.

3. Types of Decision-Making:

The decisions taken by managers at various points of time may be classified thus:

1. Personal and Organizational Decisions:

Decisions to watch television, to study, or retire early are examples of personal decisions. Such decisions, pertain to managers as individuals. They affect the organisation, in an indirect way. For example, a personal decision to purchase a Maruti rather than an Ambassador, indirectly helps one firm due to the sale and hurts another because of the lost sale. Personal decisions cannot be delegated and have a limited impact.

Organisational decisions are made by managers, in their official or formal capacity. These decisions are aimed at furthering the interests of the organisation and can be delegated. While trying to deliver value to the organisation, managers are expected to keep the interests of all stakeholders also in mind—such as employees, customers, suppliers, the general public etc. they need to take decisions carefully so that all stakeholders benefit by what they do (Like price the products appropriately, do not resort to unethical practices, do not sell low quality goods etc.)

2. Individual and Group Decisions:

Individual decisions are taken by a single individual. They are mostly routine decisions.

Advantages and Disadvantages of Group Decision-Making:

Group decisions, on the other hand are decisions taken by a group of individuals constituted for this purpose (for example, Admission Committee of a College, Board of Directors in a company). Group decisions, compared to individual decisions, have far reaching consequences and impact a number of persons and departments. They require serious discussion, deliberation and debate. The following are the advantages and disadvantages of group decision making.

Advantages:

i. A group has more information than an individual. Members, drawn from diverse fields, can provide more information and knowledge about the problem.

ii. A group can generate a greater number of alternatives. It can bring to bear a wider experience, a greater variety of opinions and more thorough probing of facts than a single individual.

iii. Participation in group decisions increases acceptance and commitment on the part of people who now see the solution as their own and acquire a psychological stake in its success.

iv. People understand the decision better because they saw and heard it develop; then paving the way for smooth implementation of the decision.

v. Interaction between individuals with varied viewpoints leads to greater creativity.

Disadvantages:

i. Groups are notorious time-wasters. They may waste a lot of time and energy, clowning around and getting organized.

ii. Groups create pressures towards conformity; other infirmities, like group think, force members to compromise on the least common denominator.

iii. Presence of some group members, who are powerful and influential may intimidate and prevent other members from participating freely. Domination is counter-productive; it puts a damper on the groups’ best problem solvers.

iv. It may be very costly to secure participation from several individuals in the decision-making process.

v. The group consists of severed individuals and hence, it is easy to pass the buck and avoid responsibility.

3. Programmed and Non-Programmed Decisions:

A programmed decision is one that is routine and repetitive. Rules and policies are established well in advance to solve recurring problems quickly. For example a hospital establishes a procedure for admitting new patients and this helps everyone to put things in place quickly and easily even when many patients seek entry into the hospital. Programmed decisions leave no room for discretion. They have to be followed in a certain way. They are generally made by lower level personnel following established rules and procedures.

Non-programmed decisions deal with unique/unusual problems. Such problems crop up suddenly and there is no established procedure or formula to resolve them. Deciding whether to take over a sick unit, how to restructure an organisation to improve efficiency, where to locate a new company warehouse, are examples of non-programmed decisions.

The common feature in these decisions is that they are novel and non-recurring and there are no readymade courses of action to resort to. Because, non-programmed decisions often involve broad, long-range consequences for the organisation, they are made by higher-level personnel only.

Managers need to be creative when solving the infrequent problem; and such situations have to be treated de novo each time they occur. Non-programmed decisions are quite common in such organisations as research and development firms where ‘situations are poorly structured and decisions being made are non-routine and complex.

The characteristics of programmed and non-programmed decisions are discussed as under:

Programmed vs. Non-Programmed Decisions:

i. Concerned with relatively routine problems. They are structured and repetitive in nature.

ii. Solutions are offered in accordance with some habit, rule or procedure

iii. Such decisions are relatively simple and have a small impact.

iv. The information relating to these problems is readily available and can be processed in a pre-determined fashion.

v. They consume very little time and effort since they are guided by predetermined rules, policies and procedures.

vi. Made by lower level executives.

vii. Concerned with unique and novel problems. They are unstructured, non-repetitive and ill defined.

viii. There are no pre-established policies or procedures to rely on. Each situation is different and needs a creative solution.

ix. Such decisions are relatively complex and have a long-term impact

x. The information relating to these problems is not readily available.

xi. They demand lot of executive time, discretion and judgment.

xii. Top management responsibility

4. Strategic, Administrative and Routine Decisions:

Strategic decision-making is a top management responsibility. These are key, important and most vital decisions affecting many parts of an organisation. They require sizeable allocation of resources. They are future-oriented with long-term ramifications. They can either take a company to commanding heights or make it a ‘bottomless pit’!

Administrative decisions deal with operational issues—dealing with how to get various aspects of strategic decisions implemented smoothly at various levels in an organisation. They are mostly handled by middle level managers.

Routine decisions, on the other hand, are repetitive in nature. They require little deliberation and are generally concerned with short-term commitments. They ‘tend to have only minor effects on the welfare of the organisation’. Generally, lower-level managers look after such mechanical or operating decisions.

The Concept of Bounded Rationality:

The classical model thus prescribes a consistent and value maximizing procedure to arrive at decisions. It turns the decision maker into an economic being trying to pick up the best alternative for achieving the optimum solution to a problem. According to the classical model, the decision-maker is assumed to make decisions that would maximize his or her advantage by searching and evaluating all possible alternatives.

The decision-making process, described in based on certain assumptions:

i. Decision-Making is a Goal-Oriented Process:

According to the rational economic model, the decision-maker has a clear, well-defined goal that he is trying to maximize. Before formulating the goal, the decision-maker can identify the symptoms of a problem and clearly specify one best way to solve the same.

ii. All Choices are Known:

It is assumed that in a given decision situation, all choices available to the decision-maker are known or given and the consequences or outcomes of all actions are also known. The decision maker can list- (i) the relevant criteria; (ii) feasible alternatives; and (iii) the consequences for each alternative.

iii. Order of Preference:

It is assumed that the decision maker can rank all consequences, according to preference and select the alternative which has the preferred consequences. In other words, the decision maker knows how to relate consequences to goals. He knows which consequence is the best (optimality-criterion).

iv. Maximum Advantage:

The decision maker has the freedom to choose the alternative that best optimises the decision. In other words, he would select that alternative which would maximise his satisfaction. The decision maker has complete knowledge and is a logical, systematic maximiser in economic-technical terms.

Causes of Bounded Rationality:

The above model is prescriptive and normative; it explains how decision makers ought to behave. Rationality is an ideal and can be rarely achieved in an organisation.

Many factors intervene in being perfectly rational, namely:

1. Impossible to State the Problems Accurately:

It is often impossible to reduce organisational problems to accurate levels. An accurate, precise and comprehensive definition of the problem as assumed under the model may not be possible. Moreover, relevant goals may not be fully understood or may be in conflict with each other. Striking a balance between goals such as growth, profitability, social responsibility, ethics, survival, etc., may be difficult and as such, the assumption that the decision maker has a single, well-defined goal in an organisational setting appears to be unfortunate.

2. Not Fully Aware of Problems:

Frequently, the manager does not know that he has a problem. If the organisation is successful and is flourishing, managers may not be in a position to assign their valuable time to searching future problems. As rightly commented by Weber’s, if current performance is satisfactory, few of us use present time to search for future problems.

3. Imperfect Knowledge:

It is too simplistic to assume that the decision-maker has perfect knowledge regarding all alternatives, the probabilities of their occurrence, and their consequences. Indeed managers rarely, if any, have access to perfect information.

4. Limited Time and Resources:

Most managers work under tremendous pressure to meet the challenges posed by internal as well as external factors. They have to operate under ‘do or die’ situations and investing more time than necessary would mean lost opportunities and consequently, lost business. This pressure to act pushes the decision managers to choose quickly. Moreover, obtaining full information would be too costly.

If resources are limited, the decisions should be taken in such a manner so as to achieve efficiency and effectiveness. Less effective solutions may be accepted, if substantial savings are made in the use of resources. Working under severe time and cost constraints, managers may settle down for less optimal decisions rather than wasting time and effort in finding an ‘ideal’ solution.

5. Cognitive Limits:

Most of the decision makers may not be gifted with supernatural powers to turn out a high-quality decision, every time they sit through a problem. They may not be able to process large amounts of environmental information, loaded with technicalities and competitive data, thoroughly.

Also, difficulties arise in relating them successfully to confusing organisational objectives. When managers are invaded with intricate details regarding various fields, they try to simplify the decision-making process by reducing the number of alternatives to a manageable number.

When the thinking capacity is overloaded, rational decisions give way to bounded decisions. Instead of considering eight to ten alternatives, managers may deal with only three or four, to avoid overloading and confusion. They simplify the ‘complex fabric of the environment’, into workable conceptions of their decision problems.

6. Politics:

The normative model, unfortunately, ignores the influence of powerful individuals and groups on the decision-making process. Many studies have revealed decision-making to be political in nature, accommodating the dissimilar and sometimes, conflicting interests of different groups (labour unions, consumer councils, government agencies, local community). In order to satisfy these groups, the decision maker may have to assign weightage to less optimal solutions, at the expense of organisational efficiency.

Thus, the rational economic model is based on a defective logic and reasoning. It is an idealistic, perhaps even naive, model of decision-making which works only when all the underlying assumptions prevail. The complexities of the real world force us to reject the traditional concepts.

We are compelled to consider a more realistic theory which receives inputs from both the quantifiable and non-quantifiable variables: a theory which ‘focuses on human involvement in the various steps of the (decision-making) process and allows for the impact of numerous environmental factors’.

Administrative Decision Making:

Bounded Rationality Approach:

The objective of the administrative model, also known as the behavioural theory, proposed by Herbert A. Simon and refined by Richard Cyert and James March, is to explain the decision-making behaviour of individuals and organisations.

According to Simon, people carry only a limited, simplified view of problems confronting them because of certain reasons:

(i) They do not have full information about the problems,

(ii) They do not possess knowledge of all the possible alternative solutions to the problem and their consequences,

(iii) They do not have ability to process competitive environmental and technical information,

(iv) They do not have sufficient time and resources to conduct an exhaustive search for alternative solutions to the problems.

Thus, human and organisational limitations make it impossible for people to make perfectly rational decisions. There are always ‘boundaries to rationality’ in organisations.

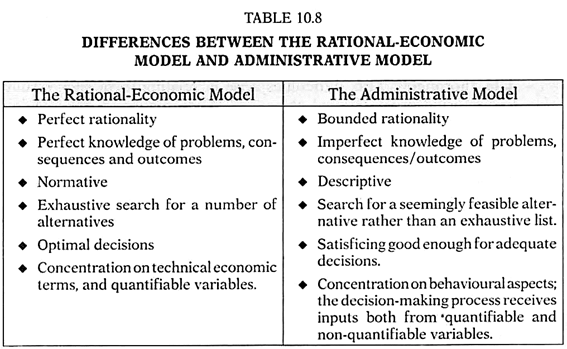

Table below explain the differences between the two theories-

What are Satisficing Decisions?

According to the behavioural theory, optimality is a Utopian concept. Again, there is no way to identify optimality and establish a measure of goodness. The decision-making process cannot be a scientific process where there are no explicit, clear-cut and idealized goals. Real life challenges, time and cost limitations, political pressures from internal and external constituencies force the decision maker to work under conditions of ‘bounded rationality’. It means that he rarely tries to find the optimum solution to a decision problem.

Instead of conducting an exhaustive search, they search for a limited number of alternatives and stop when they are able to meet the standards established by them (subjective) previously, to satisfy their goals. This search stops when they reach a point that meets their subjective standards.

They select a course of action whose consequences are good enough. Subjective rationality would be preferable to objective rationality where people have to take decisions under time and cost limitations. Thus, instead of searching for and choosing the best alternative, many managers accept decisions that are only ‘good enough’, rather than ideal. Such decisions are referred to as ‘satisficing decisions’ “the Scottish word meaning ‘satisfying’.

Examples of satisficing criteria include “fair price”, “reasonable profits”, “adequate market share”, etc. According to March and Simon, it is often, too inefficient or too costly to make optimal decisions in organisations. For example, while selecting a new employee, the organisation can just hire the first applicant who meets all the minimum requirements instead of wasting time and effort looking for an ideal personality.

Satisficing can occur for various reasons:

(i) Time pressure;

(ii) A desire to sit through a problem quickly and switch on to other matters;

(iii) A dislike for detailed analysis that demands more refined techniques;

(iv) To avoid failures and mistakes that could affect their future in a negative way.

In many situations, putting off a decision until full information is obtained may prove to be a costly mistake. It may result in lost opportunities and lost markets. Simon’s administrative model, thus, provides a highly useful approximation to how decision-makers actually operate.

It is a realistic approach. By examining decision-making process in a fragmented fashion, it provides reasonable freedom and flexibility for managers while deciding on important matters. It also highlights the importance of looking into the behavioral aspects in the decision-making process. This knowledge certainly helps in the understanding of how and why managerial decisions have been made.

4. Factors Involved in Decision-Making:

There are two kinds of factors to be considered in decision-making in favor of any alternative.

These may be classified as:

(i) Tangible and

(ii) Intangible Factors.

i. Tangible factors:

Among the tangible factors relevant to decision-making the important ones are:

(a) Sales;

(b) Cost;

(c) Purchases;

(d) Production;

(e) Inventory;

(f) Financial;

(g) Personnel and

(h) Logistics.

The effect of any decision on one or more of the tangible factors can be measured and therefore it is easy to consider the pros and cons of every decision. Decisions based on these factors are likely to be more rational and free from bias and feelings of the decision-maker.

ii. Intangible Factors:

Among the intangible factors which may influence decision-making in favor of any alternative, the important ones are the effects of any particular decision:

(a) Prestige of the enterprise,

(b) Consumer behaviour,

(c) Employee morale; and so on.

Accurate information and data about these factors is not easy to obtain. Therefore, intuition and value-judgment of the decision-maker will assume a significant role in the choice of a particular alternative.

5. Techniques and Methods of Decision-Making:

In order to evaluate the alternatives, certain quantitative techniques have been developed which facilitate in making objective decisions.

Important decision-making techniques are four and they have been discussed as under:

(1) Marginal Analysis:

This technique is also known as ‘marginal costing’. In this technique the additional revenues from additional costs are compared. The profits are considered maximum at the point where marginal revenues and marginal costs are equal.” This technique can also be used in comparing factors other than costs and revenues.

For Example – If we try to find out the optimum output of a machine, we have to vary inputs against output until the additional inputs equal the additional output. This will be the point of maximum efficiency of the machine. Modern analysis is the ‘Break-Even Point’ (BEP) which tells the management the point of production where there is no profit and no loss.

(2) Co-Effectiveness Analysis:

This analysis may be used for choosing among alternatives to identify a preferred choice when objectives are far less specific than those expressed by such clear quantities as sales, costs or profits. Koontz, O’Donnell and Weihrich have written that “Cost models may be developed do show cost estimates for each alternative and its effectiveness. Social objective may be to reduce pollution of air and water which lacks precision. Further, he has emphasised for synthesizing model i.e., combining these results, may be made to show the relationships of costs and effectiveness for each alternative.”

(3) Operations Research:

This is a scientific method of analysis of decision problems to provide the executive the needed quantitative information in making these decisions. The important purpose of this is to provide the managers with scientific basis for solving organisational problems involving the interaction of components of the organisation. This seeks to replace the process by an analytic, objective and quantitative basis based on information supplied by the system in operation and possibly without disturbing the operation.

This is widely used in modern business organisations. For Example – (a) Inventory models are used to control the level of inventory, (b) Linear Programming for allocation of work among individuals in the organisation.

Further, some theories have also been propounded by eminent writers of management to analyse the problems and to take decisions. Sequencing theory helps the management to determine the sequence of particular operations. Queuing theory, Games theory, Reliability theory and Marketing theory are also important tools of operations research which can be used by the management to analyse the problems and take decisions.

(4) Linear Programming:

It is a technique applicable in areas like production planning, transportation, warehouse location and utilisation of production and warehousing facilities at an overall minimum cost. It is based on the assumption that there exists a linear relationship between variables and that the limits of variations can be ascertained.

It is a method used for determining the optimum combination of limited resources to achieve a given objective. It involves maximisation or maximisation of a linear function of various primary variables known as objective function subject to a set of some real or assumed restrictions known as constraints.

6. Process and Steps in Decision-Making:

In decision-making process steps normally refers to processes, procedures and phases which are usually followed for better decision.

According to Stanley Vance decision-making consists of the following six steps:

1. Perception.

2. Conception.

3. Investigation.

4. Deliberation.

5. Selection.

6. Promulgation

1. Perception:

Perception is a state of awareness. In a man consciousness arises out of perception. Consciousness gives tilt to the decision-making process. The executive first perceives and then moves on to choose one of the alternatives and thus takes a decision. Perception is, therefore, an important and first step without which decisions relating to any of the problems of the organisation cannot be taken. Other steps follow “perception” is the first step in decision-making.

2. Conception:

Conception means designs for action or programme for action. Conception relates to that power of mind which develops ideas out of what has been perceived.

3. Investigation:

The investigation provides an equipment with the help of which the manager tries to go ahead with a debate either in his mind independently or with his co-workers. Perception is a sort of location of the problem whereas conception is the preparation of design or programme for solving the problem. But only perception and conception cannot offer the solution.

For solution investigation is to be carried out. Informations relevant to a particular concept is to be sought, acquired and then analysed. Relative merits and demerits of a different analysed concepts should be measured. Alternative course of action is to be thought, analysed and compared to. This needs investigation with which the manager should be armed.

4. Deliberation:

Weighing the consequences of possible course of action is called deliberation. The manager may either weigh the relative merits and demerits and the following consequences in his own mind or share his mental exercise with others to equip himself better. The deliberations remove bias and equip the manager with different ideas and alternatives and help him in arriving at a decision which may safely be ascribed as good decision.

5. Selection:

Selection is an act of the choice which in management terminology is known as decision. After deliberations one of the alternatives, the best possible in the circumstances, is selected.

6. Promulgation:

Perception, conception, investigation, deliberation and lastly selection will carry weight only when selected – the chosen alternative, that is, the decision – is properly and timely communicated to all those who are concerned and for whom the decision is meant. Only proper promulgation will help its execution.

According to the views of Mrityunjoy Banerjee – A discrimination among the available alternatives is designated as the decision. For him also decision is an act of choice – selection from different available alternatives.

He is of the opinion that a decision like planning passes through the following five phases:

(a) Defining and analysing the problem i.e., the act of perception.

(b) Finding relevant fact, i.e., the act of conception and investigation.

(c) Developing alternative solutions i.e., the act of deliberation.

(d) Selecting the best solution, i.e., the act of selection – the choice – the actual decision-making.

(e) Converting the decision into effective action, i.e., the promulgation, with the help of which the decision so taken is effectively, properly and timely communicated to all concerned.”

7. Elements of Decision-Making:

The following are the five important elements of decision-making:

(1) Concept of good decision.

(2) Environment of decision.

(3) Psychological elements in decision.

(4) Timing of decision.

(5) Communication of decision.

(1) Concept of Good Decision:

The most important task before the manager of any enterprise is to take a good decision. The objectives of an enterprise can be achieved only by a good decision. A good decision is always acceptable to all reasonable persons and is based on sound judgement and factual informations. No decision should be taken without examining the situation, correlating it with the facts and scientifically analysing the facts. Such a decision satisfies the concept of good decision.

(2) Environment of Decision:

The success and failure of the whole enterprise depends on the nature; procedure and standard of a decision taken by its manager. The organisational environment and formal structure decides the relationship between units on the one hand and individuals on the other.

This relationship forms the basis of environment prevailing in an organisation and indirectly affects a decision. Similarly, political, social and economic situation in and outside the organisation affects a decision which the manager takes for implementation by the enterprise.

(3) Psychological Elements is Decision:

Every manager takes decision on the basis of the given facts, information and scientific analysis. But out of many alternatives his choice falls on this element. It is this choice on which his psychological impact is felt. In fact psychologically manager comes closer to the choice and that is why he feels like choosing the one which he feels is in the best interest of the whole enterprise.

The manager’s habits, temperament, social environment, upbringing, domestic life and political leanings all have a trace on his choice of alternative, consequently on his decisions.

(4) Timing of Decisions:

Decision if taken at a time when it is needed helps the management in achieving the objectives more successfully. Any decision taken in time obviously leaves a lasting impression on the minds of those who are affected by the decision. The impact of the decision will have lasting effect on the personnel of the enterprise and its effect will be on the working of the enterprise.

(5) Communication of Decision:

The communication of decision is as important as taking of the decision. Both go together. Decisions if not properly and timely communicated carry no weight howsoever important or good they may be. A good decision is based on scientific analysis of facts and is taken and communicated when it is needed the most.

8. Principles of Decision-Making:

Eminent authors of management are of this opinion that on right and appropriate decisions, the success and failure of the enterprise depend. Therefore, a manager has to take all precautions before arriving at a decision.

Following are the important principles which may be taken into consideration while taking decision:

(1) Marginal Theory of Decision-Making:

Marginal theory of decision-making has been suggested by various economists. Economists believe that a business undertaking works for earning profit. To earn profit is their prime motto. That is why they agree that the manager must take every decision with the aim in view that the profit of his organisation goes on increasing till it reaches its maximum. Therefore, the economists argue that an organisation with sole aim of maximisation of profit needs a marginal analysis of all its profit. Decision-making too should be based on marginal analysis.

According to economists marginal analysis of a problem is based on Law of Diminishing Returns. With extra unit of labour and capital put in production, the production increase but it increases at a proportionately reduced rate. From every extra unit of labour and capital the production diminishes and a time comes when the increase in production stops with ‘zero’ as the production of the last unit used therein.

At this stage further production is discounted. A decision is taken to the effect that no additional unit of labour and capital now is required to be introduced in the production. Production of the last unit is marginal one where – after further introduction of extra unit becomes uneconomical or non-yielding.

The marginal principle can be effectively used while taking decision on matters relating to – (i) production, (ii) sales, (iii) mechanisation, (iv) marketing, (v) advertising, (vi) appointment and other matters where marginal theory can be scientifically and statistically used and a good decision is rendered possible.

(2) Mathematical Theory:

It will be wrong if we say that the decision-making techniques owe too much to the mathematical theory of taking decisions. Venture analysis, game theory, probability theory, waiting theory are a few of the theories on the basis of which a manager analyses a given fact and takes decision accordingly. This has given rise to a scientific approach to the decision-making process.

(3) Psychological Theory:

The nature, size and purpose, of the organisation play an important role in decision-making. Manager’s aspirations, personality, habits, temperament, political leanings and social and organisational status, domestic life, technological skill and bent of mind play a very important role in decision making. They do help in decision-making.

They all in some form or the other leave an impact on the decisions taken by the manager. No doubt the manager is not free to decide whether he wishes to. He is also bound by his responsibilities and answerability. But psychology of the manager has a bearing on the decision he takes and this fact cannot be brushed aside. Decision-making is a mental process and the psychology of those who are deliberating and of the person who take the final decision has a definite say in decision-making.

(4) Principle of Limiting Factors:

The decisions taken are based on limited factors nevertheless they are supposed to be good because of the simple fact that under the circumstances it was the only possibility. From this principle it emerges that though there are numerous alternative available to a decision-making but he takes cognizance to only those alternatives which suit the time, purpose and circumstances and which can be properly and thoroughly analysed considering the human capacity and then finally one of the alternatives is chosen which forms the basis of a decision.

(5) Principle of Alternatives:

Decision is an act of choice. It is a selection process. Out of many available alternatives the manager has to choose the one which he considers best in the given circumstances and purpose.

(6) Principle of Participation:

This principle is based on human behaviour, human relationship and psychology. Every human being wants to be treated as an important person if it is not possible to accord him a V.I.P. treatment. This helps the organisation in getting maximum from every person at least from those who have been given place of importance and honour.

Participation signifies that the sub-ordinates, even if they are not concerned, should be consulted and due weightage should be given to their viewpoint. Japanese do this. Japanese institutions – business or government make decisions by consensus. This makes all of them feel that they are very much part of the decision. The Japanese debate a proposed decision throughout its length and breadth of the organisation until there is an agreement.

A few may disagree with Japanese method of decision-making because they may agree that it is not suited to our conditions. Such a method involves politicking, delays the decisions and sometimes may result into indecisiveness. But worker’s participation in decision-making can be ensured by the Japanese method.

Those favouring Japanese method and workers participation, advance the argument that decisions are important. But according to modern thinking the decision should not be within the purview of only a selected few. Those who are to carry out the decisions must be actively associated with their decision-making also.

Principle of participation – Firstly, aims at the development and research of all possible alternatives. If larger number of people concerned are asked to search for alternatives on the basis of which decisions are expected to be taken then greater participation is assured which is surely an important aim of this principle.

Secondly, this principle asks for debating and deliberating by more and more people so as to know the mind of all and to assess the possible reaction of a particular decision which the manager has in mind.

Further, the principle of participation is becoming popular due to following reasons:

(1) The participants feel that the business is their own of which they are important parts;

(2) Opposition to a decision is considerably reduced, and those who are to carry the decision are gladly accepting even if any change is being introduced;

(3) Guidance and directions function of management are being easily performed;

(4) Decisions are the result of best possible selection of the alternatives, therefore decisions may yield results to the advantage of the organisation on the expected lines;

(5) Increase in the efficiency of workers;

(6) Development of co-ordinated efforts;

(7) Development of good human relations;

(8) Development of team spirit and better understanding because of good human relations; and

(9) Assurance of growth and prosperity to both the organisation as well as the whole working force – managerial, supervisory and operating.

Today the managers are more interested in eliciting the participation of workers with their decisions with a view to get more co-operation and to exercise effective control over them in the accomplishment of the tasks assigned by the objectives of the organisation.

9. Approaches to Decision-Making:

Decisions can be taken in different ways.

The approaches to decision-making are discussed below:

1. Centralised and Decentralised Approach:

In centralised approach to decision-making, maximum decisions are taken by top-level managers though some responsibility is delegated to middle-level managers. In the decentralised approach, the authority to take decisions is delegated to lower-level managers. In case of programmed decisions, decentralised approach is followed. Centralised approach is used to make non- programmed decisions.

2. Group and Individual Approach:

Managers take decisions with their employees/ subordinates in the group approach to decision-making process. In the individual approach, decisions are taken by the manager alone. It is the one-manager decision-making approach. The individual approach is appropriate when (i) there is emergency for taking decisions, i.e., time at the disposal of the decision-maker is limited, and (ii) resources are limited. Cost of individual decision-making is less than that of group decision-making.

Group decision-making, in most circumstances, is better than individual decision-making as decision-makers have more information to make decisions. Group decisions are easier to implement since members are morally committed to the decisions.

This approach ensures better quality and greater accuracy of decisions, improves employees’ morale, increases job satisfaction, enhances coordination and reduces labour turnover. The limitation of group decision-making is that it is “a process whereby, in response to social pressures, individuals go along with a decision even when they do not agree with it and, in order to avoid conflicts, do not even voice their reservations”.

Group decision-making has the following advantages:

(a) Decision-makers collect more information and decisions are, therefore, more scientific and accurate.

(b) Members make decisions through group thinking and are, therefore, committed to implement the decisions.

(c) Continuous interaction amongst superiors and subordinates enhances subordinates’ morale and job satisfaction. This increases communication and coordination amongst the activities of group members.

(d) It promotes creativity and innovative abilities of subordinates to make quality decisions.

Group decision-making suffers from the following limitations:

(a) It is costly and more time consuming than individual decision-making.

(b) Some members accept group decisions even when they do not agree with them to avoid conflicts.

(c) Sometimes, groups do not arrive at any decision. Disagreement and disharmony amongst group members leads to interpersonal conflicts.

(d) Some group members dominate others to agree to their viewpoint. Social pressures lead to acceptance of alternatives which all group members do not unanimously agree to.

(e) If there is conflict between group goals and organisational goals, group decisions generally promote group goals even if they are against the interest of the organisation.

Though cost of group decision-making is more than individual decision-making, its benefits far outweigh the costs and enable the managers to make better decisions.

3. Participatory and Non-Participatory Approach:

In the participatory approach, managers seek opinion of those who are directly affected by the decisions. There is no formal gathering of superiors and subordinates as in group decision-making; the decision-maker only seeks information and suggestions from employees and reserves the right of making decisions with himself. There is participation of employees in achieving the decision objectives.

In the non-participatory approach, managers do not seek information from employees as the decisions do not directly affect them. They collect information, assess it in the light of present circumstances, make decisions and communicate them to the organisational members.

4. Democratic and Consensus Approach:

In democratic approach, decisions are based on the system of voting by majority. In the consensus approach, participants discuss the problem and arrive at a general consensus. It is similar to group decision-making, where many people are involved in the decision-making process. However, in group decision-making, some people agree to others because of social or psychological pressure. Group decision-making reflects the opinion of a few and consensus decision-making reflects the opinion of all the group members.

10. Models of Decision-Making:

Models represent the behaviour and perception of decision-makers in the decision-making environment. There are two models that guide the decision-making behaviour of managers.

These are:

1. Rational/Normative Model-Economic Man

2. Non-Rational/Administrative Model

1. Rational/Normative Model:

These models believe that decision-maker is an economic man as defined in the classical theory of management. He is guided by economic motives and self-interest. He aims to maximise organisational profits. Behavioural or social aspects are ignored in making business decisions.

These models presume that decision-makers are perfect information assimilators and handlers. They can collect complete and reliable information about the problem area, generate all possible alternatives, know the outcome of each alternative, rank them in the best order of priority and choose the best solution. They follow a rational decision-making process and, therefore, make optimum decisions.

This model is based on the following assumptions:

i. Managers have clearly defined goals. They know what they want to achieve.

ii. They can collect complete and reliable information from the environment to achieve the objectives.

iii. They are creative, systematic and reasoned in their thinking. They can identify all alternatives and outcome of each alternative related to the problem area.

iv. They can analyse all the alternatives and rank them in the order of priority.

v. They are not constrained by time, cost and information in making decisions.

vi. They can choose the best alternative to make maximum returns at minimum cost.

Limitations of the Model:

Actual decision-making is not what is prescribed by the rational models. These models are normative and prescriptive. They only describe what is best, what decision-makers should actually do to make the best decisions and describe the norms that decision-makers should follow in making decisions. They do not describe how decision-makers actually behave in different decision-making situations (This is explained in the non-rational models). They only describe what the best is.

The best is, however, not achieved in real life situations because of the following constraints that managers face while making decisions:

i. They face multiple, conflicting goals and not a well-defined goal that they intend to achieve.

ii. They are constrained by their ability to collect complete information about various environmental variables. Information is future-oriented and future being uncertain, complete information cannot be collected. Many uncontrollable factors influence their ability to collect complete information.

iii. They are constrained by time and cost factors to collect the information. They are limited in their search for all alternatives that affect decision-making situations. Their decisions are based on whatever information they can collect and not complete information.

iv. They are constrained by their ability to analyse every factor that affects the decision- process. They have limited knowledge to assess all the alternatives.

v. They may base decisions on subjective and personal biases. They consider only those facts which are relevant for decision-making.

vi. Continuous researches, innovations and technical developments can turn the best decisions into sub-optimal ones. Managers are, thus, constrained by technological factors.

vii. Changing economic and social factors (economic and political policies, socio- cultural values, ethics, traditions, customs etc.) also inhibit the ability of managers to make rational decisions.

2. Non-Rational/Administrative Models:

Non-rational models are descriptive in nature. They describe not what is best but what is most practical in the given circumstances. They believe that managers cannot make optimum decisions because they are constrained by many internal and external organisational factors. Managers cannot collect, analyse and process perfect and complete information and, therefore, cannot make optimum decisions. Absolute rationality is rare.

It is seldom achieved. Based on whatever information decision-makers can gather and process, they arrive at the best decisions in the given circumstances. They are good enough and do not put undue pressure on organisational time and resources. They are easy to understand and implement. These decisions are made within the constraints or boundaries of available information and managers’ ability to process that information.

They are not optimum decisions. They are satisfying decisions. The concept of making decisions within the boundaries or limitations of managers to collect and analyse all the relevant information for decision-making is known as ‘principle of bounded rationality’. This principle was introduced by Herbert Simon.

This model is realistic in nature as it presents a descriptive and probabilistic rather than deterministic approach to decision-making. Rather than searching for all alternatives for making decisions and analysing their outcomes, decision-makers use value judgments and intuition in analysing whatever information they can collect within the constraints of time, money and ability and arrive at the most satisfying decision. This model does not represent optimum situation for decision-making. Instead, it represents the real situation for decision-making.

The decision-maker is not an economic man but an administrative man who combines rationality with emotions, sentiments and non-economic values held by the team members. He follows a flexible approach to decision-making which changes according to situations. Managers make feasible decisions which are less rational rather than rational decision which are less feasible.

“Bounded rationality refers to the limitations of thought, time and information that restrict a manager’s view of problems and situations.” — Pearce and Robinson

“Managers try to make the most logical decisions given the limitations of information and their imperfect ability to assimilate and analyse that information.” —Herbert Simon

11. Importance of Decision-Making:

Decision-making is an indispensable component of the management process. It permeates all management and covers every part of an enterprise. In fact whatever a manager does, he does through decision-making only; the end products of manager’s work are decisions and actions.

For example, a manager has to decide:

(i) What are the long term objectives of the organization, how to achieve these objectives, what strategies, policies, procedures to be adopted (planning);

(ii) How the jobs should be structured, what type of structure, how to match jobs with individuals (organizing);

(iii) How to motivate people to peak performance, which leadership style should be used, how to integrate effort and resolve conflicts (leading);

(iv) What activities should be controlled, how to control them, (controlling). Thus, decision-making is a central, important part of the process of managing. The importance of decision-making in management is such that H.A. Simon called management as decision-making. It is small wonder that Simon viewed decision-making as if it were synonymous with the term ‘managing’. Managers are essentially decision makers only.

Almost everything managers do involves decision-making. Decision-making is the substance of a manager’s job. In fact, decision-making is a universal requirement for all human beings. Each of us makes decisions every day in our lives. What college to attend, which job to choose, whom to marry, where to invest and so on.

Surgeons, for example, make life-and-death decisions, engineers make decisions on constructing projects, gamblers are concerned with taking risky decisions, and computer technologists may be concerned with highly complex decisions involving crores of rupees. Thus whether right or wrong, individuals as members in different organizations take decisions.

Collectively the decisions of these members give ‘form and direction to the work an organization does’. Some writers equate decision-making with planning. In fact, Koontz and O’Donnell viewed ‘decision-making as the core of planning’, implying that is not at the core of organizing or controlling.

However, instead of taking extreme positions, it would be better to view decision-making as a pervasive function of managers aimed at achieving goals.

According to Glueck there are two important reasons for learning about decision-making:

(i) Managers spend a great deal of time making decisions. In order to improve managerial skills it is necessary to know how to make effective decisions,

(ii) Managers are evaluated on the basis of the number and importance of the decisions made. To be effective, managers should learn the art of making better decisions.