After reading this article you will learn about:- 1. Introduction to Decision Making in Management 2. The Nature of Decision Making 3. Decision Making Defined 4. The Decision-Making Context 5. Decision-Making Conditions 6. Types of Decisions 7. Decision-Making at Different Levels in the Organisation 8. Programmed and Non-Programmed Decisions 9. How Good should the Decisions Be? and Other Details.

Contents:

- Introduction to Decision Making in Management

- The Nature of Decision Making

- Definition of Decision Making

- The Context Decision-Making

- Conditions for Decision-Making

- Types of Decisions

- Decision-Making at Different Levels in the Organisation

- Programmed and Non-Programmed Decisions

- How Good should the Decisions Be?

- Steps in Decision Making

- Group Decision Making — Use of Committees

1. Introduction to Decision Making in Management:

In today’s dynamic world business firms have to take a number of decisions every now and then. Managers know how important decision-making is from the organisational point of view. For example, in research and development management has to decide whether to pursue one or multiple design strategies. That is, should the company introduce one new high-priced stereo system or four complementary systems for each market segment?

Likewise, the production department has to decide whether to manufacture all of the electrical components or to subcontract to other firms. Similarly, the financial manager has to decide whether to invest in a new plant or to lease. Again, marketing managers have to determine the appropriate production mix with regard to price and promotion: if multiple products are produced, what should be the price range among different products? Finally, in personnel decisions have to be made about new and different pay scales and the likely impact on current wage rates.

None of the decisions is simple and it is virtually impossible for decision makers to account fully for all of the factors that will influence the outcome of the decision. As a result, the future is surrounded by uncertainty and risks have to be assumed.

Decision making is an integral part of all marginal activities including organising, leading and controlling. However, decision-making is usually most closely associated with the planning function, inasmuch as it is an important tool for most planning activities. Everyday we have to make one decision or the other. Managers are faced with a wide range of decisions on any given day. For a manager the ability to make the best professional decision is the key to success. In fact, management is basically a study of the decision-making process within an organisation.

2. The Nature of Decision Making:

The ability to make good decisions is the key to successful managerial performance. Managers of most profit-seeking firms are always faced with a wide range of important decisions in the areas of pricing, product choice, cost control, advertising, capital investments, dividend policy and so on. Managers in the not-for-profit and public enterprises are faced with a similarly wide range of decisions. For example, the Dean of the Faculty of Indian Institute of Management, Calcutta, must decide how to allocate funds among such competing needs as travel, phone services, secretarial support, and so on.

Longer-range decisions must be made concerning new facilities, new programmes, the purchase or lease of a new computer and the decision to establish an executive development centre. Public sector managers or government agencies face such decisions as the construction of a new bridge over river Hooghly, the location of the bridge, the need to support public transit systems, the enforcement of anti-monopoly laws (such as the M.R.T.P. Act) and the economic viability of setting up a Second Mumbai Airport.

A manager has always to take decisions of one sort or another. The decisions may be such as where to invest money, where to set up a new plant or warehouse, how to deal with to invest money, where to set up a new plant or warehouse, how to deal with an employee who is invariably late, or what subject should be brought into focus in the next departmental meeting. Whatever may be the nature and dimension of the problem at hand, the manager has to decide what actions need to be taken or has to arrange for others to decide.

Decision making is perhaps the most important component of a manager’s activities. It plays the most important role in the planning process.

As Stoner puts it:

“Planning involves the most significant and far-reaching decisions a manager can make. When managers plan, they decide such matters as what goals or opportunities their organisation will pursue, what resources they will use, and who will perform each required task. When plans go wrong or out of track, managers have to decide what to do to correct the deviation. In fact, the whole planning process involves managers constantly in a series of decision-making situations. How good their decisions are will largely determine how effective their plan will be.”

3. Definition of Decision Making:

Most writers on management feel that management is basically decision-making. They argue that it is only through making decisions (about planning, organizing, directing and controlling) that an organisation can be enabled to accomplish its short term and long term goals. In this article we shall discuss how managers can best go about reaching good (rational) decisions.

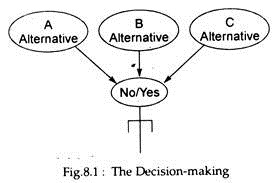

Decision making can be defined as making a choice among alternative courses of action or as the process of choosing one alternative from among a set of rational alternatives. This definition has three different but interrelated implications. See Fig.8.1.

Effective decision-making requires a clear understanding of the situation. Most people think that an effective decision is one that optimism some factor such as profits, sales employee welfare, or market share. In some situations, however, the effective decision may be one that minimises loss, expenses, or employee turnover. It may even mean selecting the best method for going out of business or terminating a contract.

1. When managers make decisions they exercise choice — they decide what to do on the basis of some conscious and deliberate logic or judgement they have made in the past.

2. When making a decision managers are faced with alternatives. As Stoner puts it: “It does not take a wise manager to reach a decision when there are no other possible choices. It does require wisdom and experience to evaluate several alternatives and select the best one.”

3. When making a decision managers have a purpose. As R. W. Morell has put it, there is hardly any reason for carefully making a choice among alternatives unless the decision has to bring them closer to same goal.

Therefore in this article the stress will be on the formal decision-making process, i.e., how managers proceed systematically to reach logical decisions that can help them in the best possible way to reach their goals.

The implication is simple enough: Managers are almost always faced with a problem or opportunity. So they propose and analyse alternative courses of action and finally make a choice that is likely to move the organisation in the direction of its goals.

We noted that effective decision requires an understanding of the situation. In a like manner, the effectiveness of any decision has to be assessed in terms of the decision-maker’s underlying goal.

4. The Context of Decision-Making:

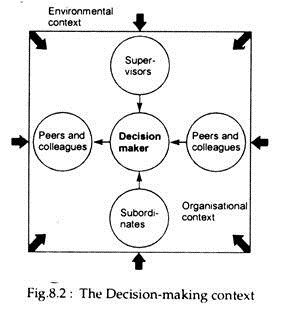

Here, we treat decision-making as essentially an individual process, but a process that occurs in an organisational context. Fig. 8.2 illustrates this point. The individual decision-maker lies at the centre of the process, but any given decision is likely to be influenced by a number of other people, departments and organisations. Fig. 8.2 shows such important influences as supervisors, peers and colleagues, subordinates, other organisational components (such as other departments and their managers), and the environment (including elements of the task environment, such as competitors and suppliers, as well as general environmental factors such as technology and the economy).

5. Conditions for Decision-Making:

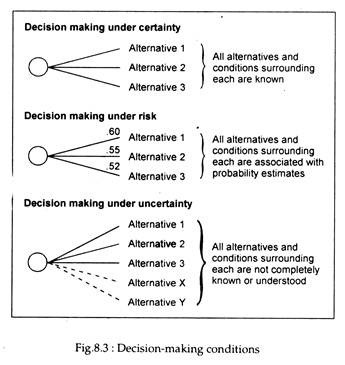

Although decision-making is essentially an individual process, the surrounding conditions can vary widely. Organisational decisions are made under three conditions, viz., certainly, risk and uncertainty. These conditions are represented in Fig. 8.3.

Decision Making Under Certainty:

When managers know with certainty what their possible alternatives are and what conditions are associated with each alternative, a state of certainty exists.

Decision Making under Risk:

A more realistic decision-making situation is a state of risk. Under a state of risk, the availability of each alternative and its potential pay-offs (rewards) and costs are all associated with profitability estimates. It is, therefore, quite obvious that the key element in decision-making under a state of risk is accurately determining the probabilities associated with each alternative.

Decision Making under Uncertainty:

However, most important and strategic decisions in modern organisations are taken under conditions of uncertainty. A state of uncertainty refers to a situation in which the decision maker does not know what all the alternatives are, and the risks associated with each, or what consequences each is likely to have.

This complexity arises from the complexity and dynamism of today’s organisations and their environments. All successful organisations have made various effective decisions under uncertainty. The key to effective decision-making under uncertainty is to acquire as much relevant information as possible and to approach the situation from a logical and rational perspective. Intuition, judgement and experience always play a very important role in decision-making under uncertain conditions.

6. Types of Decisions:

As managers “we will make different types of decisions under different circumstances. When deciding whether or not to add a new wing to the administration building, or where to build a new plant, we will have to consider our choice carefully and extensively. When deciding what salary to pay a new employee, we will usually be able to be less cautious. Similarly, the amount of information we will have available to us when making a decision will vary. When choosing a supplier, we will usually dose on the basis of price and past performance. We will be reasonably confident that the supplier chosen will meet our expectations. When deciding to enter a new market, we will be much less certain about the success of our decision. For this reason, we will have to be particularly careful making decisions when we have little past experience or information to guide us.”

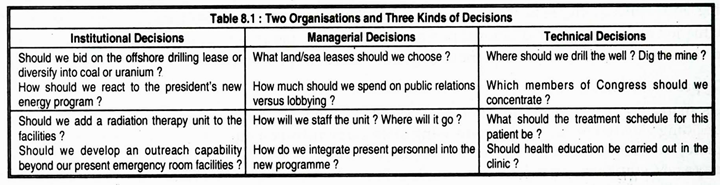

In short, the nature and circumstances of a decision can vary enormously. Managers have to vary their approach to decision-making, depending on the particular situation involved. For our purposes, it will be useful to distinguish between situations that call for programmed decisions and those that call for non-programmed decisions. Business managers have to make various types of decisions. Such decisions can be placed into three broad categories: technical decisions, managerial decisions and institutional decisions.

These three types of decisions may now be briefly illustrated:

(i) Technical Decisions:

In every organisation there is need to make decisions about core activities. These are basic activities relating directly to the ‘work of the organisation’. The core activities of Oil India Ltd. would be exploration, drilling, refining and distribution. Decisions concerning such activities are basically technical in nature. In general, the information required to solve problems related to these activities is generally concerned with the operational aspects of the technology involved.

In short, technical decisions are concerned with the process through which inputs such as people, information or products are converted into outputs by the organisation.

(ii) Managerial Decisions:

Such decisions are related to the co-ordination and support of the core activities of the organisation.

Managerial decision-making is also concerned with regulating and altering the relationship between the organisation and its external (immediate) environment. In order to maximize the efficiency of its core activities it becomes absolutely essential for management to ensure that these actions are not unduly disturbed by short-term changes in the environment.

This explains why various organisations often build up inventories and forecasting of short-term changes in demand and supply conditions are integral parts of managerial decision-making.

(iii) Institutional Decisions:

Institutional decisions concern such diverse issues as diversification of activities, large-scale capital expansion, acquisition and mergers, shifts in R & D activities and various other organisational choices. Such decisions obviously involve long-term planning and policy formulation.

In the words of Boone and Koontz: “Institutional decisions involve long-term planning and policy formulation with the aim of assuring the organisation’s survival as a productive part of the economy and society.” The implication is clear: if an organisation is to thrive in the long run as a viable organisation, it must occupy a useful, productive place in the economy and society as a whole.

With changes in society and in its economic framework, an organisation must adapt itself to such changes. Otherwise it may cease to exist. Due to shortage of traditional sources of energy the passenger car industry of the U.S. was reeling under recession from 1973 onwards. Some automobile companies faced with falling demand for petrol-operated cars have produced battery-operated motor cars.

Managers in every organisation are faced with these three types of decisions, viz., technical, managerial and institutional. Table 8.1 illustrates each type of decision for two different organisations: one profit-seeking firm (an oil company) and non-profit seeking firm (an oil company) and one non-profit organisation (a hospital).

7. Decision-Making at Different Levels in the Organisation:

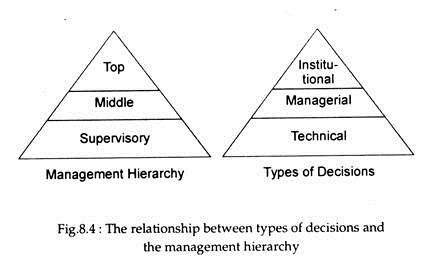

A study of the decision-making in different organisations reveals that the three types of decisions listed above are not evenly spread throughout the organisation. In general most institutional decisions are mostly made at the supervisory level. This point is illustrated in Fig.8.4.

Fig.8.4 gives an indication of the relative number of each type of decision made at each level in the organisations. However, the categories should not be treated as exclusive. For example, the production manager of a machinery manufacturing firm like the Texmaco might primarily be engaged in technical decisions, while the legal adviser of the company might be involved in institutional matters.

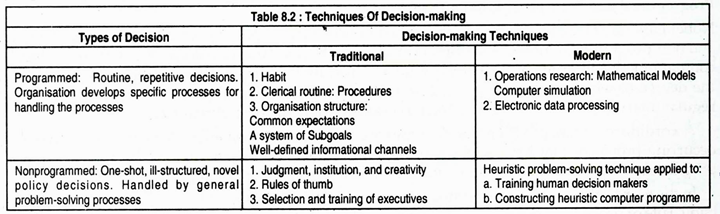

8. Programmed and Non-Programmed Decisions:

Nobel Laureate H. A. Simon has distinguished between two types of decisions, viz., programmed and non-programmed moved decisions. He has made the point that decisions differ not only in their content but also in terms of their relative uniqueness. By the term ‘relative uniqueness’ he means the degree to which a problem or decision (1) has been seen before; (2) occurs frequently and at regular intervals; and (3) has been solved or resolved in a satisfactory manner.

According to Simon, programmed decisions are those which involve simple, common, frequently occurring problems that have well-established and understood solutions. On the contrary, non- programmed decisions are those involving new, often unusual or novel problems.

In the words of Stoner:

“Programmed decisions are those that are made in accordance with some habit, rule or procedure. Every organisation has written or unwritten policies that simplify decision-making in a particular situation by limiting or excluding alternatives.”

A few examples of such decisions may now be given. In most situations managers will not have to worry about what to pay a new employee because most organisations have an established salary structure (or pay policy) for any position. (Of course, salary of highly skilled or top management is often negotiable. But these are exceptions rather than the rule).

In a like manner managers will not generally have to think about the routine problems they face every day. Their habits, or those of their peers, will help them decide quickly what to do about them.

There is no denying the fact that programmed decisions limit the freedom of managers to a considerable extent. In other words, managers hardly enjoy any discretion in matters involving programmed decisions set managers, decide what to do. This implies that programmed decisions set managers free on most occasions.

The policies, rules or procedures by which managers make decisions free them of the need to find out new solutions to every problem they face. For instance, it would really be time-consuming to decide how to handle customer complaints on an individual basis. Adoption of routine procedures such as permitting customers to exchange unsuitable merchandise would really help matters.

Since managers regularly have a series of decisions to make, organisations have to develop varying decision rules, programmes, policies, and procedures to use. Existing pay scales are used as guideline to fix the starting salary of a new factory guard or a new security officer. Similarly, when inventory of raw materials occurs.

What can be said in favour of programmed decisions is that such decisions can be made “quickly, consistently and inexpensively since the procedures, rules and regulations eliminate the time-consuming process of identifying and evaluating alternatives and making a new choice each time a decision is required. While programmed decisions limit the flexibility of managers, they take little time and free the decision maker to devote his or her efforts to unique, non-programmed decisions. It is perhaps easiest for managers to make programmed decisions.”

It is perhaps easiest for managers to refer to a policy rather than think of some problem and suggest solution. Effective managers usually rely on policy as a time saver. But they must remain alert for any exceptional case(s). For example, in case of a multi-product firm like the Godrej, the company policy may put a ceiling on the advertising budget for each product.

However, a particular product, say Cinthol, may demand an expensive advertising campaign to counter a competitor’s aggressive marketing strategy. In such a situation a programmed decision — that is a decision to advertise the product in accordance with budget guidelines — may prove to be wrong. Thus when a situation calls for a programmed decision managers must ultimately make use of their own judgement.

Non-programmed decisions, as Stoner has put it, are “those that are out of the ordinary or unique. If a problem is complex or exceptional, or, if it has not come up often enough to be covered by a policy, it must be handled by a non-programmed decision.”

Such decisions are needed to solve problems like how to allocate an organisation’s resources, what to do about a failing product line, how community relations should be improved, and almost all significant problems a manager faces. In Table 8.2, we prepare a list of the traditional and modern techniques of decision-making.

In those organisations and decision situations where non-programmed decisions are the rule, the creation of alternatives and the selection and implementation of the most appropriate one becomes the distinction between effective and ineffective managers is drawn on the basis of their ability to make good non- programmed decisions.

However, managers are often evaluated on the basis of their ability to solve problems, to apply creativity and judgement to the solution of problems and to make decisions in a logical, step-by-step manner. Since established procedures are of little use for making such decisions, new solutions are to be found out.

This explains why most management training programmes are directed towards improving a manager’s ability to make non-programmed decisions by teaching them how to take such decisions.

9. How Good should the Decisions Be?

In traditional economic theory it is argued that the objective of the business manager is to maximize something. This is, of course, a realistic assumption provided the decision maker is able to obtain complete information concerning all possible alternatives and thus choose the best solution designed to achieve a particular goal. The manager will choose to maximize profit or some other value.

However, 1978 Nobel Laureate H. A. Simon has made extensive study of managerial behaviour and on the basis of his investigation arrived at the conclusion that modern managers do not always attempt to maximize profits. Since managers are often forced to make decisions in the absence of complete information there is departure from the goal of profit maximization. Managers rarely consider all possible alternatives to the solution of a problem. Rather they examine a few alternatives that appear to be likely solutions.

Most non-programmed decisions involve innumerable variables and it is neither possible nor feasible, with limited knowledge and resources, to examine them all. Therefore, Simon argues that instead of attempting to maximise, the modern manager satisfies.

The manager, in fact, examines four to five alternative possibilities and chooses the best possible option from among them, rather than investing the time necessary to examine thoroughly all possible alternatives.

Satisficing:

An important concept developed by Simon is satisfying, which suggests that, rather than conducting an exhaustive search for the best possible alternative, decision makers tend to search only until they identify an alternative that meets some minimum standard of sufficiency.

In the case of the manager who must choose a site for a new plant, some of the minimum requirements for the site may be that it must be within 500 meters of a railroad spur and within 2 kilometers of a major highway, be located in a community of at least 40,000 people, and cost less than Rs. 1,000,000.

After a period of searching, the manager may locate a site 490 meters from a railroad spur, 1.8 kilometers from a highway, in a community of 41,000 people, and with a price tag of Rs. 950,000. The satisfying concept suggests that she or he will select this site even though further searching might reveal a better one.

People tend to satisfice for a variety of reasons. Managers may simply be unwilling to ignore their own motives and therefore not be able to continue searching after a minimally acceptable alternative is identified. The decision maker may be unable to weigh and evaluate large numbers of alternatives and criteria. Subjective and personal considerations often intervene in decision situations. For example, the final criterion used to select a plant site might be its proximity to the manager’s home town. For all these reasons, the satisfying process plays a major role in decision-making.

H. A. Simon makes the following assumptions about the decision-making process:

1. Decision makers have incomplete information regarding the decision situation.

2. Decision makers have incomplete information regarding all possible alternatives.

3. Decision makers are unable or unwilling, or both, to fully anticipate the consequences of each available alternative.

One important concept that Simon derived from these ideas is the notion of bounded rationality. He specifically notes that decision makers are limited by their values and unconscious reflexes, skills and habits. They are also limited by less-than-complete information and knowledge.

Further, he argues that “the individual can be rational in terms of the organisation’s goals only to the extent that he is able to pursue a particular course of action, he has a correct conception of the goal of the action, and he is correctly informed about the conditions surrounding his choice. Within the boundaries laid down by these factors his choices are rational-goal-oriented.”

Essentially, Simon suggests that people may try to be rational decision makers but that their rationality has limits.

Consider the case of a manager attempting to decide where to locate a new manufacturing facility. To be rational, he or she must have the power and ability to make the correct decision, must clearly understand what the new facility is to do, and must have complete information about all alternatives. It is very unlikely that all of these conditions will be met, so the decision maker’s rationality is bounded by situational factors.

According to Simon modern managers act within bounded rationality. The central feature of the principle of bounded rationality is Simon’s contention that the so-called ‘administrative man’ does not follow an exhaustive process of evaluation of the options open to find a course of action that is satisfactory or good enough. This Simon calls ‘satisfying’ and he describes it in contrast to the actions of ‘economic man’, who selects the best possible option from among those that are available.

Simon states in Administrative Behaviour that managers ‘satisfies’, that is, look for a course of action that is satisfactory or good enough. The inference is that rather than optimizing in the strict sense of proceeding to a maximum they consider all the constraints bearing on the decision situation and choose a course of action that is satisfactory to them (i.e., good enough under the present circumstances).

In short, the concept of bounded rationality refers to “boundaries or limits that exist in any problem situation that necessarily restrict the manager’s picture of the world. Such boundaries include limits to any manager’s knowledge of all alternatives as well as such elements as prices, costs and technology that cannot be changed by the decision maker.”

Consequently the manager hardly strives to reach the optimum solution but realistically attempts to reach a satisfactory solution to the problem at hand.

In fact, Simon’s view of the modern manager is different from the views of other writers on management. He attempts to present a realistic picture of a decision maker who is faced with two sets of constraints — internal and external. The former include such things as the individual’s intellectual ability (or-inability), training and experience, personality, attitudes and motivation.

The latter refer to all external influences — influences exerted by workers of the organisation and groups outside it. Simon does not attempt to prove that managers do not attempt to make effective decisions. He only recognizes the very important fact that more often than not, decisions are balanced with the cost (measured in terms of time and money) of making it.

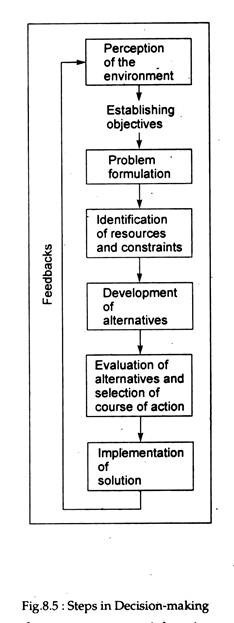

10. Steps in Decision Making:

There are various types of decisions such as setting up a new area or adding or dropping a new product on the product line, or hiring additional sales persons to increase the market share for a particular product, or even dismissing a worker. Whatever may be type of decision the decision maker has to proceed through a number of well-defined and interrelated steps. Some decisions can be made in a minute’s time.

On the contrary, others may take months or years. Some decisions may be made hurriedly and thus prove to be ineffective. On the contrary, some decisions may be taken after much deliberation and careful consideration of alternatives. But all decisions have to proceed through these steps. Fig. 8.5 illustrates the steps in the decision-making process. However, the actual process of decision-making may not be as rational as Fig. 8.5 implies.

1. Recognising and Defining the Decision Situation,

2. Perception of the Environment,

3. Establishing Objectives,

4. Problem Formulation,

5. Identification of Resources and Constraints,

6. Development of Alternatives,

7. Evaluation of Alternatives and Selection of a Course of Action,

8. Implementation,

9. Feedback, and

10. Follow-up and Evaluation.

1. Recognising and Defining the Decision Situation:

The first step in making a decision is recognising that a decision is necessary — there must be some stimulus to initiate the process. For example, when an important equipment breaks down, the manager has to decide whether to repair or replace it.

Moreover, the manager must also be able to define the situation. This is partly a matter of determining how the problem that is being addressed came about. This is an important step because situation definition plays a major role in subsequent steps.

2. Perception of the Environment:

The manager does not operate in a certain environment. Assessing the effect of possible future changes in the environment is an essential step in decision-making. The term ‘environment’ here covers all factors external to the firm. This explains why the decision maker must become aware of and be sensitive to the decision environment before any decision is possible.

This sensitivity results from two inputs:

1. Specific information which is of relevance to the decision maker (such as cost control reports, quality control reports, periodical sales reports, data on raw materials prices, etc.).

2. General information which are impressionistic in nature about conditions and operations (such as the manager’s ‘feel’ for the situation).

It is necessary to distinguish, at the outset, between the environment as an objective entity and the manager’s perception of the environment. Most often than not decision makers filter the information they receive, i.e., they pay more attention to some information than to other information. This practice sometimes prove to be disastrous to both the decision maker and the organisation.

The manager’s primary task is to monitor the environment for potential change. In fact, in every management information system there is an in-built early warning signal system of reporting various environmental developments such as new or adapted products by competing producers; changes in attitudes and sentiments of buyers; development of new processes or methods of production.

If the organisation is to survive and grow in the long nm it must be ready to adapt and evolve in response to diverse environmental changes. In short, while strategy should not be conceived as exclusively concerned with the relation between the enterprise and its environment, assessing the effects of possible future changes in the environment is an essential task in strategy formulation.

There are two steps to this process: the first is to consider how the relevant environmental factors may change; the second is to assess the strategic implications of such changes for the firm.

3. Establishing Objectives:

When a manager makes a decision, he (she) chooses from some set of alternatives as the one he (she) believes will best contribute to some particular end result. That is, decisions are made within the context of, and influenced by, the objective or set of objectives defined by the decision maker. Thus the second step in the decision process is to establish objectives or to take account of those that have been previously defined.

Objectives have to be defined in a concrete, operational form, since if these are stated in a general or vague form, it becomes virtually impossible to establish whether or not a particular decision brings one closer to the stated goal.

Consider, for example, the following two ways in which a firm might state one of its objectives:

Objective A:

To increase our share of the market.

Objective B:

To increase our market share by at least 3.5% in the next fiscal year.

With ‘Objective A’, the firm has little way to evaluate the effectiveness of various decisions as they relate to their goal. A 0.001% increase in market share satisfies the objective, as does a 1% increase, or 10% increase. However, with an objective stated as in B, there would be less room for debate about success or failure.

The firm either increases market share by the prescribed amount in B might be revised. If the firm consistently achieves a given objective, then the objective might be reviewed or changed to prevent under-achievement.

4. Problem Formulation:

With objectives firmly in hand, the next phase in the decision process is to define the particular problem that gives (give) rise to the need to make a decision. The fact that someone must make a decision implies that there is a problem to be solved. In defining or formulating a problem the decision maker should be as precise as possible and should state the problem explicitly. Problems act as barriers to the achievement of organisation goals.

In other words, they act as obstacles to be overcome by the decision makers — when an organisation fails to achieve its goals, a performance gap is said to exist. This gap reveals the difference between the predicted or expected level of performance and the actual level.

Problem formulation seems to be the most neglected aspect of the decision-making process. More often than not it is simply assessed that the nature of a managerial problem is obvious to all concerned. A major problem, however, is that managers often feel psychologically uncomfortable to think about problems.

Moreover, since time management is a very real part of managerial work manages devote much of their time for problem solving and not for problem formulation. In general managers simply do not give themselves sufficient time to consider the situation and do an effective job of problem formulation.

5. Identification of Resources and Constraints:

Just as a business manager does not operate in isolation, problem solving does not occur in vacuum. In fact, problem solving lies embedded in the fabric of the organisations and its external environment. The truth is that most organisations face a multiplicity of problems at the same time. These problems compete for the limited amount of organisation’s resources and manager’s attention.

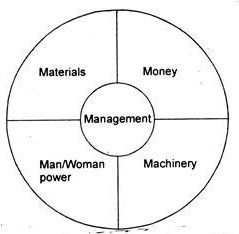

Anything that contributes to problem solving is a resource which includes time, money, personnel, experience, equipment, raw materials and information. Managers use various types of resources and we often speak of five Ms in this context, viz., materials, money, manpower, machinery and management. See Fig.8.7.

Fig. 8.7: Basic resources of the organisation – the five

However, managers are faced with various constraints in the decision-making process. A significant constraint is, of course, lack of adequate resources. Other constraints may be unfavourable government policy (such as the MRTP Act which acts as a constraint on the expansion of the so-called large houses in India), or adverse attitude of employees (due to lack of motivation and morale). In general constraints are factors that impede problem solution or limit managers in their efforts to solve a problem.

The decision maker has to develop a brief explicit list of the major resources which enables the decision maker to make the best possible utilization of the organisation’s resources. In other words, such an exhaustive list permits the decision-maker to budget organisational assets in order to maximize their usefulness.

In a like manner the listing of constraints “alerts the decision maker to the important stumbling blocks affecting a solution so that they can be avoided.” Furthermore, “organisations sometimes confront situations in which the absence of a specific resource or the existence of a particular constraint is a significant problem itself.”

6. Development of Alternatives:

The generation of various possible alternatives is essential to the process of decision-making. Perhaps the most important step in decision-making process is to develop alternative courses of action to deal with the problem situation. It is generally useful to design the process in such a way that both obvious, standard solutions and creative, informative solutions or alternatives are generated.

In general, the more important the decision, the more attention is directed to developing alternatives. If the decision involves where to build a multi-crore rupee office building, a great deal of time and expertise will be devoted to identifying the best locations.

Although managers should encourage creative solutions, they should also recognise that various constraints often limit their alternatives. Common constraints include legal restrictions, moral and ethical norms, authority constraints, or constraints imposed by the power and authority of the manager, available technology, economic considerations and unofficial social norms.

In most real-life situations managers adopt a shortcut approach and thus fail to arrive at the best solution. In fact, managers often identify one or two alternatives very fairly and choose from among them. So more effective alternatives are not considered. Writers on organisations have suggested that creativity is needed at this stage in developing various possible alternatives for consideration.

How much time and money should be developing alternatives:

Time and money are the important resources at the disposal of the decision-maker. However, time seems to be the ultimate scarce resource of the manager. Moreover, since there are always additional alternatives waiting to be discovered, the process of generating alternatives could conceivably go on forever.

Managers should consider three proximate factors in determining the appropriate amount to spend in generating alternatives. Firstly, managers should assess how important is this problem or opportunity. The more important the decision the greater the value of marginal improvements in the solution.

The second factor is the ability of the decision-maker to differentiate accurately among alternatives determining the amount of time that he should devote in developing alternatives and cannot, in advance, tell the difference between two alternatives and cannot rank them accurately according to this likely effectiveness.

Thirdly, the larger the number of people concerned with a problem, the greater the number of likely alternatives to be sought.

In this context Boone and Koontz have opined that: “when dealing with complex problems effecting numerous people, it is often necessary to compromise on some points. But compromises by their very nature require participants to sacrifice some of their interests. This can lead to considerable dissatisfaction or frustration. These ‘human costs’ are often considerable” even though these cannot be measured in terms of money.

7. Evaluation of Alternatives and Selection of a Course of Action:

The next step in the decision-making process is evaluating each of the alternatives generated in the previous step. Usually each alternative has to be assessed to determine its feasibility, its satisfactoriness, and its consequences. This step lies at the heart of the decision-making process. All the previous steps have been of a preparatory nature and it is in this step that the manager finally decides what to do.

This crucial stage has the following three distinct but closely interrelated phases:

(i) Determining feasible alternatives:

In case where a large number of alternatives have been generated, it is quite likely that many of them will not appear to be feasible. There are two reasons for this. Either the resources necessary to implement the alternatives are not available. Alternatively there may be prohibitive constraints.

As Boone and Kurtz have argued: “if judgement was suspended during the creative generation of alternatives in the previous step, most of the alternatives generated would fall into the infusible category. Separating the feasible alternatives from the infeasible ones saves time, since the decision maker can then evaluate only those alternatives that are likely to be chosen.”

(ii) Evaluation of alternatives:

The evaluation of alternatives is no doubt a complex exercise. In fact many of the operations research techniques developed during the last few decades are methods of determining the relative efficiency of various alternatives.

Alvar Elbing has proposed the following five rules for evaluating alternatives:

1. A solution should have substantial quality so that it can meet organisational goals.

2. A solution has to be acceptable to those affected by it and to those who must implement it.

3. A solution has to be evaluated in terms of the anticipated responses to it.

4. The risks of each alternative must be considered.

5. The choice of solution should focus on present alternatives, not past possibilities.

Is quality consistent with goals?

In order to assess the quality of a solution we have to reintroduce the concepts of efficiency and effectiveness. In fact, the quality of a solution has these two dimensions. Efficiency may be reinterpreted as the ratio of output to inputs. In other words, it is a measure of organisational productivity. It therefore lies at the heart of business cost-benefit analysis.

On the contrary, effectiveness is a measure of the extent to which an alternative meets the stated objective (regardless of the costs involved). Before attempting to evaluate the quality of any alternative, it is absolutely essential for the decision-maker to first establish the extent to which each of these criteria will be used.

(iii) Choosing the Most Appropriate Alternative:

After evaluating the alternatives properly it is necessary to choose the alternative which is acceptable to those who must implement it and those who have to bear the consequences of the decision. Failure to meet this condition often results in the failure of the whole decision-making process to solve problems. In fact, choosing the best alternative in terms of facilities, satisfactoriness and affordable consequences is the real crux (or the essence) of the decision-making process.

A related point may be noted in the context. It is possible to assess the acceptability and efficacy (efficiency) of a proposed solution by considering the anticipated responses to it. Such a response refers to the reaction of the organisation and its individual members to an alternative that has been chosen. This should be of critical concern to the manager or decision maker.

The solution is simple to find: even a technically mediocre solution may prove to be ‘effective’ (in the sense defined above) if it is implemented with enthusiasm and dedication. On the contrary, the technically correct alternative may fail to evolve sufficient response or succeed if it is implemented in half-hearted and haphazard fashion.

This explains why most writers on management stress the importance of including as many members of the organisation as feasible in the decision-making process. True, “participation in problem solving by organisational members should increase their receptiveness to the chosen alternative.”

It is also necessary to consider the various types of risks associated with each alternative. In fact, different risks are involved for different individuals and groups in the organisation. It may be stressed at this stage that the differences among those who make decision, those who implement them and those who must live on them should not be minimised.

8. Implementation:

After one or more alternatives have been selected, the manager must put the alternative or alternatives into effect. In some situations, implementation may be fairly easy; in other situations it may be quite difficult. However, since most managerial problems are intimately concerned with the human element in the organisation, implementation of solution is no doubt a complex exercise.

It is to be noted that so far no generalised rules have been developed that deal with managing the implementation phase.

However, three questions must be answered at the phase:

Firstly, what should the internal structure of implementation be? In other words, what should be done? When? By whom? Since the solution of most managerial problems requires the combined effort of various members of the organisation, each must understand what role he (she) has to play during each phase of the implementation process.

Secondly, how can the manager reward organisation members for participating in the implementation of the proposed solution? Decisions are no doubt made by managers but these are carried out by other members of the organisation. So managers must ensure that those who are responsible for implementation have some stake — financial or otherwise — in the success of the solution.

Thirdly, how provisions for evaluation and modification of the chosen solution during the implementation process be made? As implementation of solution proceeds, organisation members should be able to modify the solution based on what they learn during implementation.

But unless some specific provision is made for modification of the chosen solution, the chosen alternative may be left untouched and implemented without any thought of possible modification — even in those situations where minor adjustments would produce better solutions.

The key to effective implementation is action planning, a well thought out, step-by-step description of the programme. Some appropriate techniques for solving organisational problems arising from decision situations are tactical plans, operational plans and programmes, and standing plans. A programme, for example, might be developed for the sole purpose of implementing a course of action for solving an organisational problem.

Another problem to consider when implementing decisions is people’s resistance to change. There are various reasons for such resistance such as insecurity, inconvenience and fear of the unknown. Hence, it will be judicious on the part of managers to anticipate potential resistance at various stages of the implementation process.

Managers should also recognise that “even when all alternatives have been evaluated as precisely as possible and consequences of each alternative weighed, it is likely that unanticipated consequences will also arise. Unexpected cost increases a less-than-perfect ‘fit’ with existing organisational subsystems, unpredicted effects on cash-flow or operating expenses, or any number of other situations could develop after the implementation process has begun”.

9. Feedback:

Feedback is “a necessary component of the decision process, providing the decision maker with a means of determining the effectiveness of the chosen alternatives in solving the problem or taking advantage of the opportunity and moving the organisation closer to the attainment of its goals.”

In order to make such an evaluation of the effectiveness of a possible decision, the following three conditions must be fulfilled:

Firstly, there must exist a set of standards which act as yardstick against which to compare performance. For example, if the sales goal of a company in the next quarter is Rs. 2 lakhs more than the current quarter, the relevant standard is present sales turnover plus Rs. 2 lakhs. Likewise if a company adopts a zero defect programme, a zero rejection rate for output becomes the relevant standard.

Secondly, performance data must be readily available so that the comparison to standards may be made. The chief approach to formulating the data collection process is the design of management information systems.

Finally, it is absolutely essential to develop a data analysis strategy. Such a strategy includes a formal plan which outlines how the data will be used. However, one unfortunate characteristic of most data are never used for decision-making purposes. The problem is not insoluble.

In fact, “managers who know exactly how the data are to be analysed will be able to specify the types of the data they need, the most preferred format, and the time sequence in which they are needed.” Such advance specifications are likely to act as aids in reducing the mass of useless data that are often collected.

10. Follow-up and Evaluation:

As the final step in the decision-making process, managers should be very sure to evaluate the effectiveness of their decision. That is, they should make sure that the alternatives chosen in step 5 and implemented in step 6 have accomplished the desired result.

When an implemented alternative fails to work, the manager has to respond quickly. There are several ways of doing it. One of the alternatives that was identified previously (the second or third choice) could be adopted.

Alternatively, the manager might recognise that the situation was not correctly defined to start with and begin the decision-making process all over again. Finally, the manager might decide that the alternative originally chosen is in fact appropriate, but that it simply has not yet had time to work or should be implemented in a different way.

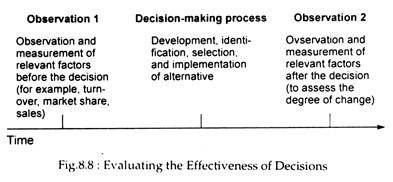

Fig. 8.8 shows an effective process for evaluating alternatives. Prior to the actual decision, existing conditions relevant to the decision itself are observed, assessed and measured. Finally, a post decision observation should be made to determine how successful the decision was in solving the original problem.

11. Group Decision Making—Use of Committees:

The steps in the decision-making process descried so far focused primarily on the individual decision maker. However, in practice, most of the decision in large, complex organisations are made by groups. This often creates additional problems (which are often of a complex nature) because of shared power, bargaining activities and need for compromise present in most group decisions.

Group decision-making is the accepted norm in Japanese organisations. Use is made of committees in the decision-making process. The process starts with supervisory managers meeting as a group to analyse a problem or opportunity and develop alternative solutions.

Two or three of the most likely alternatives are then presented to top management which makes the final decision. Lower level managers are used in the preliminary stages of the decision process. They are entrusted with responsibilities in decision-making. At the same time the amount of time top management must devote to the process is considerably reduced.

The practice in America is just the opposite. American managers often criticise the group (or committee approach) on two major grounds. Firstly, it is thought to be a waste of time. Secondly, this is treated as a method of obtaining only compromise solutions.

However, the fact remains that today’s complex world in which most organisations operate makes it increasingly difficult for a single manager to make complex decisions independently. Even in America task forces, conferences, committees and staff meetings are widely made use of in arriving at important (and often strategic) decisions.

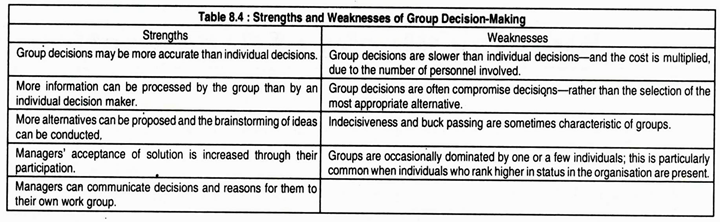

Strengths and Weaknesses:

Strengths:

Group decision-making has its merit and drawbacks. Empirical evidence available so far suggests that decision made by groups are more accurate than those made by individuals. This is more so in those situations involving complex problems where no one member is a specialist in the problem area.

The saying ‘two brains are better than one’, like many others, contains an elephant of truth. The implication of this statement in the present context is clear: more information can be processed by the various group members.

A second advantage of this method is that “the presence of several group members also means that more alternative solutions may be proposed and a great number of proposed solution can be analysed.”

Thirdly, managers’ acceptance of solution is increased through their participation.

Fourthly, managers can communicate decisions and their rationale to their own work groups.

Finally, a major strength of group decision-making is the relative ease of implementing decisions that have been made.

Weaknesses:

However, there are certain weaknesses of the group decision-making process.

These are the following:

Firstly, group decisions are slower than individual decisions and are more costly in terms of time and money due to the number of personnel involved.

Secondly, more often than not group decisions are comprehensive decisions resulting from differing points of view of individual members, rather than the selection of the most appropriate (or the best possible) choice for solving the problem.

In the opinion of Boone and Koontz: “There is often pressure to accept the decision favoured by most group members. Group-think — a phenomenon in which the time for group cohesiveness and consequence becomes stronger than the desire for the best possible decision — may occur. Some groups experience more indecisiveness than individual decision makers since the pressure to reach a decision is diffused among the group members.”

Thirdly, group decision-making is characterised by indecisiveness and buck passing — blaming one another for a poorly made decision or the lack of decision. This occurs in situations where clear lines of authority and responsibility for making a decision have not been drawn. This phenomenon can, of course, be prevented if the leader accepts ultimate responsibility for decision-making.

Finally, Normal R. F. Maier has pointed out that, in most instance, one person or a few individuals will dominate the group because of differences in status or rank from the other members or through force of personality. The table below summarizes the advantages and disadvantages of group decision-making.