In this article we will discuss about:- 1. Stages of Decision Making 2. Types of Decisions 3. Process 4. Theories 5. Organisation.

Contents:

- Stages of Decision Making

- Types of Decisions

- Decision Making Process

- Theories of Decision Making

- Organisation of Decision Making

1. Stages of Decision Making:

In an important sense, management is synonymous with decision making. About the stages in decision making,

Simon identifies three criteria:

(a) Intelligence:

Searching for problems, and identifying and defining problems that demand action. More briefly, what is the problem?

(b) Design:

Formulating alternative courses of action, and identifying their likely costs and consequences. More briefly, what are the alternatives?

(c) Choice:

Selecting a particular course of action from the various alternatives. More briefly, what alternative is best?

Thus, we need to understand the following three points:

(a) The proportion of time devoted to each of these activities will vary from one situation to another, from one level of authority to another, and from one manager to another.

(b) Each stage is in itself a complex decision making process, as each problem generates sub-problems and requires application of all these three criteria.

(c) The identification of stages does not guarantee easy solution of managerial problems but does assist the managers in some way or other.

2. Types of Decisions:

If organisations are viewed as a hierarchy of decision making and decision makers, it implies that, at different levels of the organisation, management will be concerned with different types of decision.

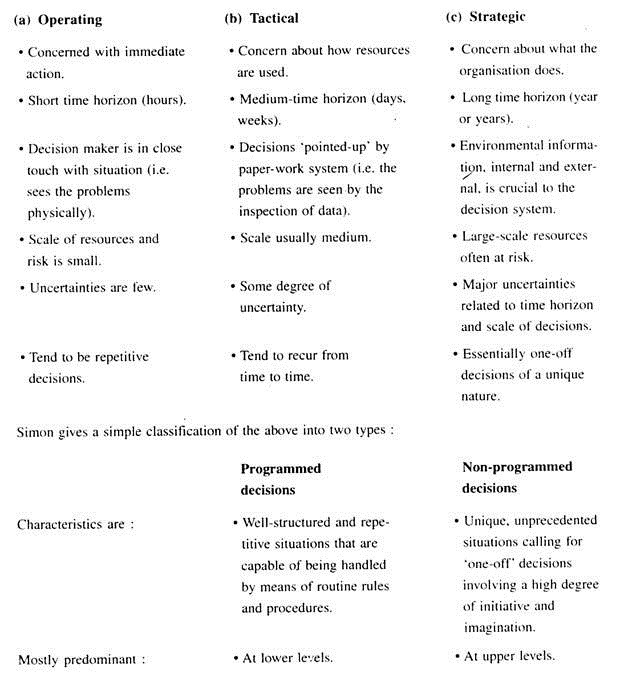

An outline classification of decision making is given below for comprehension:

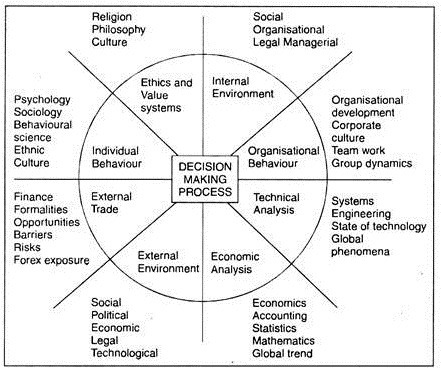

The decision making process is very complex. There is no simple analytical model upon which basic strategic choices are made. The above diagram shows that a large number of disciplines influence and interact on strategic decision making in organisations.

The readers must understand that there are no neat formulas to quantify and determine how much of each discipline will apply to a particular problem nor how much weight a decision maker should give to each of the disciplines.

3. Decision Making Process:

From company to company, and within the same company, the decision process is constantly changing. Furthermore, major strategic decisions tend to be, in most cases, unique to each organisation.

4. Theories of Decision Making:

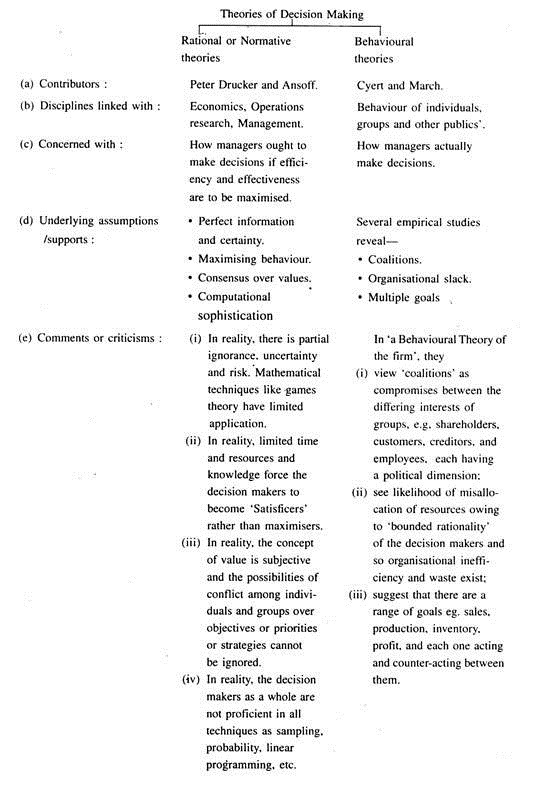

The theories of decision making, in a broad classification, are of two types:

(i) Rational or Normative and

(ii) Behavioural.

Their characteristics and general theme are presented next.

On the rationality approach to decision making, Simon observes: ‘In terms of what objectives, and whose values, shall rationality be judged?

On the basis of this question, he has identified four types of rationality in decision making:

(i) ‘Objectively’ rational, if it maximises given values in a given situation.

(ii) ‘Subjectively’ rational, if it maximises attainment of given values in the context of the ‘bounded’ or limited knowledge of the decision maker (that is, bounded rationality).

(iii) ‘Organisationally’ rational, if it is oriented to the attainment of organisational goals or objectives (for example, Peter Drucker’s seven objectives discussed hereafter on ‘Planning’).

(iv) ‘Personally’ rational, if it is oriented to an individual’s goals.

It is interesting to note that Cyert and March also emphasise the on-going political process involved in the reconciliation of such goals. They say, ‘organisations do not have objectives, only people have objectives’. Thus organisational objectives are the end-product of a complex and continuous interaction between individuals and groups within and outside the organisation.

5. Organisation of Decision Making:

In the organisation of decision making, there are basically two crucial schemes:

(1) Centralisation and Decentralisation, and

(2) Departmentalisation.

(1) Centralisation and Decentralisation:

Possibly Henry Fayol (1841-1925) was modern in this concept. According to him, ‘everything which goes to increase the importance of the subordinate’s role is decentralisation, and everything which goes to reduce it is centralisation; the question of centralisation or decentralisation is a simple question of proportion, it is a matter of finding the optimum degree for the particular concern.’

There are a range of factors that affect the ‘optimum’ proportion.

Of them, three major factors are:

(a) The size of the organisation (the larger the organisation the more difficult it is to exercise detailed control from the centre);

(b) The degree of diversity in the activities being controlled (it is easier to centralise the control of similar activities than dissimilar ones); and

(c) The quality of superiors and subordinates (the centralisation presupposes competent superiors and decentralisation competent subordinates).

The history of the enterprise and the philosophy of management are also other criteria.

The positive features of decentralisation are:

(i) It reduces the load on top management,

(ii) It encourages initiative and drive of middle and junior management,

(iii) It enables quick decisions, and

(iv) It assists in the appraisal of managerial performance.

The negative features of decentralisation are:

(i) Closer coordination and control by the top management are rendered difficult,

(ii) Some duplication of effort and activities takes place,

(iii) Uniform application of policies and standards is difficult at times.

Centralisation and decentralisation are, thus, complex issues. Certain types of decision require centralisation and certain types decentralisation. Again certain departments may be centralised and others decentralised. And so, we find that many US companies which went multinational adopted divisional structure and attempted to combine centralised control with decentralised operations.

(2) Departmentation:

This issue should be discussed along with the matrix structure of an organisation. There are many ways in which decision makers can be departmentalised.

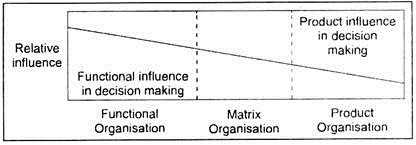

But the main approaches could be summarised in a diagram next:

It combines the advantages and disadvantages of both functional and product organisations, and the optimum balance between them would yield results in the strategic choices and applications.

Two basic points emerge therefrom:

(i) The interrelationship between organisational choices over centralisation and decentralisation, and

(ii) The relevance of a management dictum that ‘structure follows strategy’.

One important caution to a practising manager is that he should be a conflict-resolver and a joint delegator in his total task and should see to the practical realities of organisational decision making, without having a massive structural upheaval.