This article throws light upon the four main elements of marketing mix. The elements are: 1. Product Mix 2. Price Mix 3. Promotion Mix 4. Distribution Mix.

Element # 1. Product Mix:

The product means anything that is offered to a market for its use or consumption. The product can be a physical object or a service or some kind. The product offered by a manufacturer consists of physical items, such as machine tools, television sets, loaves of bread or cosmetics.

Products offered by service industries include hospital care, dental treatment, holiday arrangements and accountancy services, for example. The range of products offered by an organization is called the product mix. Since most, if not all, of the organization’s revenue is going to be obtained from the sale of its products, it is clearly important that the range and quality of the product mix is frequently evaluated and amended.

Examples of a product mix are as follows:

(1) Motor car manufacturer:

Cheap, basic family runabouts, medium-priced family saloons, estate cars, executive saloons, and sports cars. Within most of these product lines, various other refinements can be offered e.g. two-door and four-door versions of the family saloons, hatch-backs as an alternative to the estate models, variations in engine sizes, and, of course, a range of colours.

(2) District hospital:

Surgical and medical services, diagnostic services, para-medical services, pre-natal advice and others. Within each of the major product lines various alternative services are offered e.g., general surgical, accident services, coronary care, X-radiography, physiotherapy, pre-natal classes and so on.

In considering products, it is important to note that people generally want to acquire the benefits of the product, rather than its features. For example, in buying a motor car a person is buying such things as luxury or speed or economy or status. The fact that these benefits are achieved by differences in engine size, suspension design or paintwork is really of secondary interest.

Similarly, the reason why we want hospitals is for such aims as the preservation of life or the improvement of health or peace of mind. Whether these things are achieved by surgery, or by drugs, or by nursing care, or by modern diagnostic apparatus is, for many people, a matter of secondary importance.

The very existence of a product range is, in itself, a selling point for a product. The same consideration applies to other aspects of the product, such as quality, brand, packaging and after-sales service, where applicable. Where quality is designed into a product, the benefits can be long product life, absence of faults and subsequent breakdowns, reliability, increase in value and many others.

However, product quality may not be sought after at all. For example, the benefits of disposable goods are immediate and one-off. Such goods do not need to be durable or aesthetic, so long as they are hygienic and functional such as disposable syringes. Thus product quality may be high or low, depending on the wants or preferences of the market, and part of an organization’s product strategy is to decide the level of quality to be aimed at.

One important method used to sell benefits is by branding products. This means applying the organization’s signature to its product by the use of special names, signs or symbols. Branding has grown enormously during this century, and there is hardly a product which does not have a brand name. Famous brand names include Coca Cola, Luxor, Rotomec etc., all of which have become synonymous with certain categories of products, like soft drinks, ball pens etc.

In general, branding is a feature of consumer products. It is less common in industrial products. Packaging is an important factor in the presentation of a product to the market. Not only does packaging provide protection for the product, but it can also reinforce the brand image and the point-of-sale attraction to the buyer. The protective aspect of packaging is vital in respect of items such as foodstuffs, dangerous liquids and delicate pieces of machinery.

Goods such as soft toys and items of clothing may not need such protection, but here other considerations apply, such as the appearance of the goods on the shelf, or the possibility of seeing the contents through the packaging.

Other aspects of packaging may emphasise the convenience of the pack, as for example in cigarette packets which may be opened and reopened several times, or beer cans, which can be opened safely by pulling a ring.

Some products are sold with a very strong emphasis on after-sale service, warranties, guarantees, technical advice and similar benefits. Mail-order firms invariably have an arrangement whereby, if customers are not satisfied with the goods received, they may return them at the firm’s expense without any questions being raised.

Computer suppliers frequently provide customer training as an integral part of their total product package. In recent years the growth of consumerism or consumer protection lobbies has led to many organizations taking action to improve the service to the customer after the sale has been concluded.

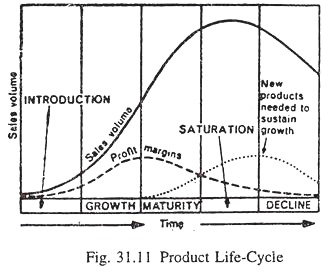

Emphasis on the make-up of the product is not only vital because of the need to sell benefits to potential customers, but also to take account of another key factor i.e. the product life-cycle. Studies have shown that most products pass through a series of stages – their life-cycle – from the time they are introduced until the time they are withdrawn. A product will typically pass through five major stages in its life.

These are shown in the diagram below (Fig. 31.11).

The consequences of these stages of the product life-cycle are as follows:

Costs are high (because they include the development costs), sales and profits are low. Few competitors. Price relatively high.

Growth:

Sales rise rapidly. Profits at peak level. Price softens. Increasing competition.

Unit costs decline. Mass market appears.

Maturity:

Sales continue to rise, but more slowly. Profits level off. Competition at its peak. Prices soften further. Mass market.

Saturation:

Sales stagnate. Profits shrink. Measures taken against remaining competition. Prices fiercely competitive. Mass market begins to evaporate.

Decline:

Sales decline permanently. Profits low or even zero. Product is withdrawn from the market.

The total length of time over which a product may decline depends on a variety of factors, such as its relevance to basic needs, its adaptability in the light of economic trends and whether it is the focus of short-term fads or of longer-lasting fashions.

A basic foodstuff, such as a packet of ground coffee, will have a relatively long life-cycle. Conversely, in an economy where energy costs are high and fuel conservation is the fashion, the expensive motor car with a high petrol consumption will tend to have a short life-cycle, but the economy car will continue for years.

Taking into account the various stages of the product life-cycle and the period of time concerned, it is possible to plan the product mix, plan the development and introduction of new products, plan the withdrawal of obsolete or unprofitable products, and set the revenue targets for each product within the total range.

If the current position of any one product is plotted correctly on its life-cycle, then it is possible to assess the potential growth of sales, or the degree to which prices should be allowed to soften in order to maintain the market share, or whether the product should be superseded by another. Thus the concept of the product life-cycle makes an important contribution to forecasting of sales and planning of products.

Element # 2. Price Mix:

If product is the most important single element in the marketing mix, then price is usually next. Price is important because it is the only element of the mix which produces revenue; the others all represent costs.

Sellers have to gear prices to a number of key factors, such as:

(a) The costs of production (and development),

(b) The ability to generate sufficient revenue and/or profits,

(c) The desired market share for the product, and

(d) The prices being offered by the competitors.

2. Price is especially important at certain times. For example:

(a) When introducing new products,

(b) When placing existing products into new markets,

(c) During periods of rising costs of production,

(d) When competitors change their price structure,

(e) When competitors change other elements in their marketing mix (e.g., improving quality or adding features without increasing prices), and

(f) When balancing prices between individual products in a product line.

When a new product is introduced, such as a video or a home computer, the price tends to be high on account of the initial development and marketing costs. This sort of product tends to be directed, initially, to higher-income groups or specialist-interest groups. As the product begins to attract increasing sales, and initial costs begin to be covered, then prices can be reduced and production volume stepped up.

However, it is also possible to introduce a product with a very low price in order to obtain a foothold in a new market, or an increased share of an existing market. A bargain price may well attract considerable sales and at the same time discourage competitors. The danger is, of course, that the price may be so low that the business fails to generate sufficient revenue to cover its operating and/or capital costs.

Few products stand still in terms of their costs. Labour costs increase from year to year; materials costs and energy costs may be subject to less regular, but sharper, increases; interest rates may be extremely variable, and hence the cost of financing products fluctuates.

Many costs can be offset by productivity savings. Therefore, the costs which are the most crucial are those which represent sudden and massive increases, which cannot be absorbed by improving productivity.

In this situation price increases are practically inevitable, and the question is by how much should we increase them? In certain situations, it may be possible to gain a temporary advantage over competitors by raising prices by the lowest possible margin, and offering some other advantage such as improved after sales service or credit terms.

The activities of competitors have an important bearing on pricing decisions. The most obvious example is when a competitor raises or lowers his prices. If your product can offer no particular advantages over his, then if he drops his price, you will have to follow suit. If, on the other hand, you can offer other advantages in your marketing mix, there may be no pressure at all to reduce your price.

If a competitor raises his price, perhaps because of rising costs, it may be possible to hold yours steady, provided you can contain your own rising costs. Pricing is a very flexible element in the marketing mix and enables firms to react swiftly to competitive behaviour.

Competitors may throw out a challenge by improving the product and offering a better distribution service, for example. This kind of behaviour, too, can be countered by price changes – in this case by easing prices and/or improving credit terms. Much will depend on the sensitivity of the market to price changes.

If price is the dominant issue for buyers, then they will prefer lower price to slightly higher quality or improved distribution arrangements. If price is not the major factor in the buyer’s analysis, then marginal extra quality and delivery terms may prove the more attractive.

Finally price is important in determining the relative standing of one product or product-line vis-a-vis another within the product mix. This issue applies particularly in highly differentiated products in the consumer area. It is important, for example, that a motor car manufacturer establishes appropriate differentials between different models within a product-line e.g., between 1000 cc and 800 cc models.

If 800 cc models are selling well but 1000 cc models are not, it may be in the seller’s interests to reduce the differential so as to attract more buyers to the 1000 cc models. Otherwise a reasonable differential will be expected in order to justify the enhanced engine rating of the larger model.

The concept of a loss-leader is often applied to internal price-differentials. This means that one product in a line is reduced to below-cost levels with the aim of attracting attention to the product-line or range as a whole.

So, for example, a new fibre-tipped pen, in a range of such pens offered by a newcomer to the market, may be sold at a loss in order to draw attention to the range as a whole, and to establish a share of the total market. Loss-leaders naturally represent very good value for money to the buyer, and can be a very useful way of establishing a range in the market-place.

Element # 3. Promotion Mix:

Every product need to be promoted that is to say it needs to be drawn to the attention of the market-place, and its benefits identified. The principal methods of promotion are: advertising, personal selling, sales promotion and publicity. It is in these areas that Marketing departments come into their own. They provide the bulk of the expertise, and carry the biggest amount of responsibility, in respect of these aspects of the marketing mix.

The aim of an organization’s promotional strategy is to bring existing or potential customers from a state of relative unawareness of the organization’s products, to a state of actively adopting them. Several different stages of customer behaviour have been identified.

These can be stated as follows:

Stage 1 Unawareness of product.

Stage 2 Awareness of product.

Stage 3 Interest in product.

Stage 4 Desire for product.

Stage 5 Conviction about value of product.

Stage 6 Adoption/Purchase of product.

The four different methods of promotion are applied, where appropriate, to each of the stages of customer behaviour. Advertising and publicity have the broadest applications, since they can affect every stage. Personal selling and sales promotion activities, by contrast, tend to be more effective from Stage 3 onwards.

Before describing each of the methods in greater detail, one further point can be made about them as a whole. This is that they have a different emphasis according to whether they are being applied to consumer markets or industrial markets.

For example, whilst advertising is very important in reaching out to consumer markets, it is of relatively little significance to industrial markets, where personal selling is the most popular method. Publicity and sales promotion activities appear to rank equally between both types of market.

(A) Advertising:

Advertising is the process of communicating persuasive information about a product to target markets by means of the written and spoken word, and by visual material. By definition the process excludes personal selling.

There are five principal media of advertising as follows:

(a) The press – newspapers, magazines, journals etc.,

(b) Commercial television,

(c) Direct mail,

(d) Commercial radio, and

(e) Outdoor – hoardings, transport advertisements etc.

Whatever the medium a number of questions must be decided about an organization’s advertising effort.

These are basically as follows:

1. How much should be spent on advertising?

2. What message do we want to put across?

3. What are the best media for our purposes?

4. When should we time our advertisements?

5. How can we monitor advertising effectiveness?

Advertising expenditure:

If the product is at the introductory stage, a considerable amount of resources will be put into advertising. Conversely, if the product is in decline little or no expenditure on advertising will be permitted. If the product is at the saturation stage, advertising may well be used to score points off the competition e.g., “our vehicle does more miles per gallon than theirs (naming specific competing models).” Advertising expenditure may be related to sales revenue or it may base on what the competitors are spending.

Advertising message:

Probably the most important aspect of any advertising campaign is the decision about what to say to prospective customers, and how to say it. This is the message which aims to make people aware of the product and favourably inclined towards it. Advertising copy (i.e., the text) also aims to make people desire the product. The entire process is the fundamental one of turning customer needs into customer wants.

The advertising message should aim at, to:

(a) Increase customer familiarity with a product (or variations of it e.g. brand, product-range etc.).

(b) Inform customers about specific features of a product.

(c) Inform customers about the key benefits of a product.

Choice of media and time:

The choice of media depends on the organization’s requirements in terms of:

(a) The extent of coverage sought to reach customers,

(b) The frequency of exposure to the message,

(c) The effectiveness of the advertisement i.e., is it making a relevant impact,

(d) The timing of the advertisement, and

(e) The costs involved.

If wide coverage is sought (e.g. for a new Do-it-Yourself product or a new consumer banking service), then a television advertisement put out at a peak viewing time would be the most effective.

For effectiveness, magazines and journals tend to reach the most relevant markets, provided they are selected carefully in the first place. For example, advertisements for camping enthusiasts will tend to produce better results in camping magazines than in national newspapers or magazines aimed at other interest groups, such as Collectors of antique furniture.

One of the problems with magazine advertisements, however, is their relatively long lead-time before an advertisement appears. Newspapers are better media on this score. Direct mail scores high on relevance-it can be directed very specifically at certain markets, but because of the personnel costs, it can be expensive. In the final analysis, organizations have to weigh up the anticipated benefits of particular media against the costs involved. This brings us on to the question of how do organizations assess the effectiveness of their advertising?

Advertising effectiveness:

There are two main ways of looking at the question of advertising effectiveness – the first is to consider the results of the advertising in achieving target improvements in specific tasks e.g. increasing brand awareness in a specific market; the second it to consider the impact of advertising on sales.

(B) Personal Selling:

However vivid the message put over by advertising, there is no substitute for the final face-to-face meeting between the buyer and the seller or his representative. Advertising creates the interest and the desire, but personal selling clinches the deal. In industrial markets, personal selling plays an even more extensive role. For the moment, let us consider the basic sales process.

This is generally understood to mean:

(a) Establishing customer contact,

(b) Arousing interest in the product,

(c) Creating a preference for product,

(d) Making a proposal for a sale,

(e) Closing the sale, and

(f) Retaining the business.

So far as consumer markets, and especially mass markets, are concerned, advertising must play a vital role in the first three stages of the process. After that, advertising becomes rapidly less important, and personal selling takes over. By comparison, advertising plays a much less important role in industrial markets. Where even the first stage is dominated by personal selling. However, personal selling is the most expensive form of sales promotion.

(C) Sales Promotion:

Sales promotion activities are a form of indirect advertising designed to stimulate sales mainly by the use of incentives. Sales promotion is sometimes called “below-the-line advertising” in contrast with above-the-line expenditure which is handled by an external advertising agency. Sales promotion activities are organized and funded by the organization’s own resources.

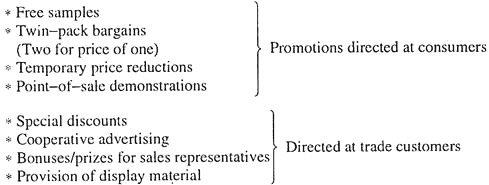

They can take a number of different forms, as, for example:

There are ‘push’ and ‘pull’ strategies. Sales promotion falls into the first category. It aims to push sales by offering various incentives at, or associated with, the point-of-sale. Its use is most frequent in the field of consumer products.

The objectives of a promotion directed at consumers could be to:

(a) Draw attention to a new product or line.

(b) Encourage sales of slow-moving items.

(c) Stimulate off-peak sales of selected items.

(d) Achieve higher levels of customer acceptance/usage of a product or product-line.

Objectives for a trade-orientated promotion could be to:

(a) Encourage dealer/retailer cooperation in pushing particular lines.

(b) Persuade dealers/retailers to devote increased shelf-space to organization’s products.

(c) Develop goodwill of dealers/retailers.

The most popular method of evaluating a sales promotion is to measure sales and/or market share before, during and after the promotion period. The ideal result is one which shows a significant increase during the promotion, and a sustained, if somewhat smaller increase after the promotion.

Other methods of evaluation could include interviewing a sample of consumers in the target market (e.g., to check if they had seen the promotion, changed their buying habits etc.), and checking on dealers’ stock-levels, shelf-space etc.

(D) Publicity:

Publicity differs from the other promotional devices, in that it often does not cost the organization any money! Publicity is news about the organization or its products reported in the press and other media without charge to the organization. Of course, although the publicity itself may be free, there are obvious costs in setting up a publicity programme, but, these are considerably lower than for advertising, for example.

Publicity usually comes under the heading of public relations, which is concerned with the mutual understanding between an organization and its public. Sponsorship events in the arts and sports are becoming an increasingly popular form of publicity.

Concerts, both live and recorded, have been promoted jointly by the musical interests concerned and by industrial and commercial interests. Athletics meetings, tennis tournaments and horse-races have all been the subject of sponsorship.

Again, although the publicity itself is free, the costs of sponsorship are not. Nevertheless, such activities can contribute significantly to an organization’s public image. Organizations which are selling products that are the target of health or conservationist lobbies are often to be found sponsoring activities such as sporting events and animal welfare campaigns.

Thus patronage of sports, the art and learning are all useful means of gaining publicity in a manner which casts a favourable light on the organization, and, ultimately, on its products.

Element # 4. Distribution Mix:

Moving the product or service to the final customer/consumer is the purpose of distribution.

Distribution is primarily concerned with:

(a) Channels of distribution.

(b) Physical distribution.

(a) Channels of distribution:

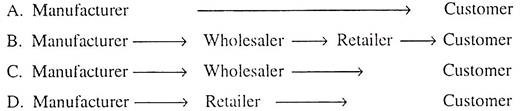

Channels of distribution are the marketing institutions which facilitate the movement of goods and services from their point of production to their point of consumption. Some channels are direct as when a computer firm sells its product direct to the users.

Others, the majority, are indirect. This means that there are a number of Intermediaries between original producer and eventual buyer, as in the case of the box of foreign-made chocolates bought at a local retailer.

The choice of channels utilised by a producer is determined ultimately by the customer, and in recent years there has been a trend towards shorter channels, as customers, especially in consumer markets, realise that there are price advantage to be gained when middlemen, or retailers, are by-passed in the chain of distribution. Thus direct mail, cash and carry, and ‘pick your own’ (fruit, vegetables etc.) operations are increasing in response to consumer interest in this approach.

The most common channels of distribution and the role played by the various intermediaries in them is explained below:

Channel A represents a direct marketing channel. This is to be found more in industrial markets than in consumer markets. Manufacturers of goods such as machine tools, computers, ships and other large or expensive items tend to move them direct to the buyer without involving middlemen or intermediaries.

However, this practice is becoming more frequent in consumer markets as well. For example, in mail order operations and in door-to-door selling (e.g. cosmetics, household wares and double glazing).

The reasons for direct channels are basically as follows:

Industrial markets:

Relatively small number of customers; need for technical advice and support after the sale; possible lengthy negotiations on price between manufacturer and customer; dialogue required where product is to be custom-built.

Consumer markets:

Lower costs incurred in moving product to consumer can lead to lower prices in comparison with other channels; manufacturers can exercise greater control over their sales effort when not relying on middlemen.

Channel B represents the typical chain for mass-marketed consumer goods. Manufacturers selling a wide range of products over a wide geographical area to a market numbered in millions would find it prohibitively expensive to set up their own High-street stores, even if they were permitted to proliferate in this way. For such manufacturers (e.g. of foodstuffs, confectionery, footwear, clothing and soaps, to name but a few), middlemen are important links in the chain.

Wholesalers, for example, buy in bulk from the manufacturers, store the goods, break them down into smaller quantities, undertake advertising and promotional activities, deliver to other traders, usually retailers, and arrange credit and other services for them. Their role is important to both manufacturer and retailer.

The role of the latter is to make products available at the point-of-sale. Individual consumers need accessibility and convenience from their local sources of consumable products. They also need to see what is available, and what alternatives are offered.

A retail store, whether owned by an independent trader or a huge supermarket chain, offers various advantages to consumers: stocks of items, displays of goods, opportunity to buy in small quantities, and convenient access to these services.

So far as manufacturers and wholesalers are concerned the retailer is, above all, an outlet for their products, and an important source of market intelligence concerning customer buying habits and preferences.

Channel C represents one of the shorter indirect channels, where the retailer is omitted. This kind of operation can be found in mail-order businesses, and in cash-and-carry outlets. The former are usually composed of the larger mail-order firms, offering a very wide range of goods (and some services, too). They buy from manufacturers, store and subsequently distribute direct to customers on a nation-wide basis.

Their ability to attract customer in the first place relies heavily on:

(a) Comprehensive, colorful and well-produced catalogues, and

(b) The use of part-time agents, usually housewives, working on a commission basis.

Whilst such an operation does not generally offer any price advantage over a retail business, it is a very convenient way of choosing goods and there is always extended credit available.

With the wider use of computers in the home, and the prospects, in the not-too-distant future of being able to order goods via a telephone link, mail-order business seems likely to grow. Cash-and-carry outlets usually deal in groceries, and many are open only to trade customers. They tend to rely on a rapid turnover of stock, to keep down inventory levels.

Their main advantages for buyers are:

(a) Price, which is significantly lower than in a retail operation, and

(b) The opportunity to buy small-bulk quantities.

Unlike mail-order businesses, they serve relatively local and specialised markets.

Channel D is another version of a shorter, indirect channel. In this case, it is the wholesaler who is removed from the scene.

Not surprisingly, the retailers who dominate this channel are powerful chains or multiples in their own right. Some such retailers, as in the footwear trade, concentrate on one range of goods only. They buy in bulk from manufacturers and importers, and distribute direct to their retail outlets.

They usually offer a wide selection of lines, and are very competitively priced. Other large retail groups handle a diversity of goods, which are again competitively priced, and made available in prime shopping areas.

Market segmentation is undertaken by suppliers in order to get a clearer picture of the market-place in order to offer a particular marketing mix to one or more segments. The concept assumes that within any single market there are invariably other sub-markets.

Consumer markets are usually segmented on the basis of geography, demography and buyer-behaviour. Industrial markets are segmented in a roughly similar fashion, but also include consideration of trade groups and end-use.

Geographical variables — Region, population density, climate etc.

Demographic variable — Age, sex, family size, occupation, social class etc.

Buyer-behaviour variables — Usage rate, benefits sought, brand loyalty, life-style etc.

(b) Physical distribution:

Whereas channels of distribution are marketing institutions, physical distribution is a set of activities. The former provide the managerial and administrative framework for moving products from supplier to customer. The latter provide the physical means of so doing. Physical distribution is concerned with order processing, warehousing, transport, packaging, stock/inventory levels and customer service.

In recent years a number of attempts to integrate and coordinate these functions has come to be called Physical Distribution Management. This aims to integrate the activities of marketing, production and other departments in this aspect of the organization’s marketing task.

The degree of attention paid to physical distribution depends considerably on the proportion of total costs taken up by distribution costs. If the product is a high-quality, high-cost item, then distribution costs will probably represent a small proportion of total costs of manufacturing and marketing it, and so physical distribution may be considered very much a secondary issue.

Where the product is offered at a very competitive price, and hence where profit margins may be tight, all overhead costs will be carefully examined. In this situation distribution costs will form an important issue for the supplier.

An important feature of such costs is that they tend to increase rather than decrease with sales volume. Whereas unit production costs tend to benefit from increased volume of production, distribution costs tend to worsen.

A high level of customer service also tends to greatly increase distribution costs. For example, if a customer requires 100% delivery from stock within two days, this means carrying extra stock levels as a buffer against any shortfall in supplies to the warehouse. If that customer could be persuaded to reduce his requirements to, say, 80% delivery within two days, this might affect useful savings in distribution costs.