This article throws light upon the three categories under which plans are classified in an organisation. The categories are: 1. The Time Dimension in Planning 2. The Use Dimension in Planning 3. The Scope or Breadth Dimension in Planning.

Category # 1. Time Dimension in Planning:

a. The Time Dimension in Planning:

Time enters as an important variable in the planning process. The time available to develop a new product or a method of production, to overcome a safety hazard, react to a business contraction or acquire another firm varies widely.

A few plans take several years to complete. It is interesting to note that about 15 years had passed between the initial development of the Xerox electrostatic copier and its full- scale commercial introduction.

Corporate (or long-range) planning involves all the departments of a company in the context of assumptions about development in the market environment, etc., and, therefore, the desirable development of new products and new areas of business. It involves the assessment of external threats and opportunities and internal strengths and weaknesses, and the evaluation of alternative strategies.

Corporate planning represents “a systematic attempt to influence the medium and long-term future of the enterprise by defining company objectives; by appraising those factors within the company and in the environment which will affect the achievement of these objectives; and by establishing comprehensive but flexible plans which will help ensure that the objectives are in fact achieved.”

The time span covered by a corporate plan does vary from company to company and is often influenced by such factors as the time it takes to bring new plan into operation or develop or launch a new product. Most plans, however, involve looking ahead between five and ten years.

The basic question to be answered here is: What should we be doing now to help us reach the position we want to be in five to ten years’ time? It is now widely agreed that plans should reach far enough into the future to cover the subject under consideration.

b. The Commitment Principle:

It is important to note at this stage that the length of the planning period is determined by the commitment principle. The implication is simple enough: the time period covered by planning should be related to the commitments of the organisation. The commitment principle was first developed by Harold Koontz and Cyril O’Donnell in 1955.

The principle states that an organisation should plan for a period of time in the future sufficient to fulfill the commitments of the organisation which result from current decisions.

In the opinion of Boone and Koontz, planning must encompass a sufficiently long period of time to fulfill the commitments resulting from current decisions. A long-range plan is superimposed upon the foundations of short and intermediate-range plans, all attainable within a specified time period.

c. Short, Intermediate and Long Range Planning:

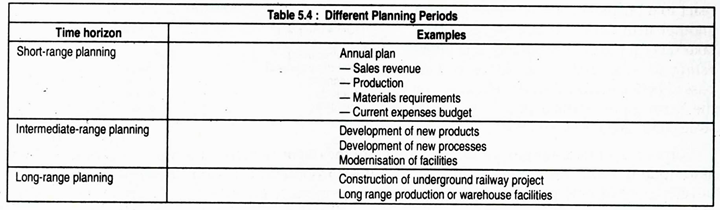

Corporate planners and managers often make use of the following time frames in describing planning periods:

Short range: One year or less.

Intermediate range: Between one and five years.

Long range: Between five to ten years or more.

The planning activities for each of the different time horizons do differ from organisation to organisation. For example, the Jay Engg. Co. (P) Ltd., Calcutta, may view six months as a relatively short planning period in planning major expenditures for new generating facilities. The Maruti Udyog Ltd. has invested more than ten years in research activities aimed at developing several new models of cars and jeeps.

Category # 2. The Use Dimension in Planning:

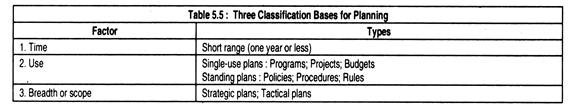

Plans are often divided into two broad categories on the basis of their usage: single use plans for recurring or long term activities, including policies, procedures and regulations provide continuing guidance to the actions or expected actions of organisation members.

But organisations also make use of other types of plans that are considered as one-shot or single-use—that is, these are essentially non-recurring. Single-use plans refer to certain predetermined courses of action which are developed for relatively unique, non repetitive situations.

The decision of Indian Airlines to shift its head-quarter from Delhi to Mumbai required numerous one-time plans. The most prevalent single-use plans are programmes, projects, budgets and organisational plans.

Programmes:

A programme is basically a large-scale, single-use plan involving various (and often numerous) interrelated activities. It specifies the objectives, major steps necessary to achieve these objectives, individuals or departments responsible for each step, the order of the various steps, and resources to be deployed (employed).

Another example is the joint Indo-U.S.S.R. programme to send astronauts on the moon. In a small organisation a programme (or several programmes) may be developed for reducing absenteeism and improving employee morale.

In the words of L.B. Curzon, “Programmes are single-use plans comprising relatively wide, related activities and requiring complex patterns of co-ordination. They involve policies, and the objectives which have generated them, procedures, sequence of rules, time schedules and (often) capital and operating budgets.”

An example of a ‘major programme’ is the range of co-ordinated activities needed to carry out any firm’s decision to convert from the manufacture of small cars to large commercial vehicles. A minor programme is exemplified by a firm’s arrangements to provide intensive training for its supervisory staff. It may be noted that the key to success of a programme is skill in co-ordinated planning.

In this context a passing reference may be made to budgets which are statements, in quantified terms, of future expenditures and revenues, reflecting resources, allocated to specified activities within a fixed (stated) time period (usually an accounting or financial year).

They mirror basic organisational plans and are used as guides to — and control of — standards of performance. Budgets are related to objectives. Hence they permit the use of management by exception, when it becomes possible to check and analyse budget variances. In this way they act as signals for corrective actions to be taken.

Projects:

A project is a single-use plan that is either a component of a programme or that is on a smaller scale than a programme. The Underground Railway Project of Calcutta was originally divided into numerous specific sub-programmes. The sub-programmes were, in their turn, then divided into specific projects. Each project was then assigned to a contractor for completion.

These projects resembled closely small-scale programmes, since each contractor’s assignment contained the same steps present in a programme. Other examples of projects include the installation of new machinery in a plant, or a plan to enlarge the seating capacity of Eden Gardens Stadium (Calcutta).

Budgets:

A budget is simply a statement in quantitative and usually financial terms of the planned allocation and use of resources. It can be defined as a financial plan listing in detail the resources or funds assigned to a particular programme project, product or division.

It is detailed plan or forecast of the resources, expected from an officially recognised programme of operation, based on the highest reasonable expectations of operating efficiency. It is generally expressed in monetary terms.

Furthermore, budgets are important components of both programmes and projects. However, budgets are also considered as single-use plans since “the process of developing budgets is clearly planning and coordinating other activities.”

A budget is a statement of planned revenue and expenditures — by category and period of time —of money, time, personnel, space, buildings, or equipment, expressed in numerical terms. It shows the future of the company in financial terms, i.e., in terms of money. On the contrary, budgetary control involves careful planning and control of all the activities of the organisation.

It assumes a genuine desire on the part of management to keep as close to the previously charted course as possible, to check actual performance against the plans and to use the budget as a road map to reach the previously established goals.

Quotas:

Sales or marketing plan is an important aspect of a company’s operational plan. It is because a company makes profit by selling its output. This is vital for its survival and growth. Moreover, the sales forces are often compensated on the basis of its actual performance.

A significant overall objective for many incentive plans is management’s desire to focus clearly the attention of the sales force on a few well-established goals critical to the enterprise’s marketing plans and to provide suitable reward for appropriate effort.

The most prevalent component of incentive payment is the achievement of sales volume objectives either on a quota or absolute volume basis. Required total sales volume is set on the basis of (1) amount of available business and (2) desired profit margins implying a certain level of plant utilization.

Territorial standards are generally used in well-established markets. Territories are grouped into small, medium and large categories whose volume levels are fixed for an extended period of time. Incentives may be paid to the degree that actual sales exceed certain norms or sales volume.

Every sales territory should carry an assigned quota indicating its contribution to profit and volume and its sales activity requirements. The three different but interrelated types of quotas for a territory are: (1) profit quota by product line or by service, (2) rupee sales volume quota by product line or by service, and (3) activity quota in terms of demonstrations, tests, seminars, sampling, trade shows etc.

Policies and Strategy:

Standing plans may be divided into three major categories — policies, procedures and rules — on the basis of their scope. Policies refer to statements of aims, purposes, principles or intentions which serve as continuing guidelines for management in accomplishing objectives. In short, policies are general guidelines for decision making.

Some policies are considered important enough to be imbedded in the corporate charter or in its by-laws (or articles of association). These can be changed only by vote of its shareholders and are the broadest and most fundamental of corporate policies. Typically, the choice of industry is stated in the purpose clause, and the scale operations vaguely fixed by the authorised capital structure. Many companies refer other matters to annual shareholders’ meeting, e.g., pension plans, plans for major financing operations, and profit-sharing.

Somewhat less significant (or more urgent) plans and choices are made by the board of directors. These policies tend to be company wide in scope, crossing departmental lines, although a few departmental matters may reach the board through financial importance alone. Choice of industry seems to be the most fundamental of company policies, underlying and limiting all departmental policies.

In its broadest sense, this choice is usually written into the corporate charter and thereby reserved to the shareholders’ discretion. However, within these broad limits, the board may decide to take on a new line or to discontinue an old one. For example, the board of directors of a manufacturer of plastic fire-brick may decide to bring out a line of air-setting materials or a manufacturer of thermostatic controls may add a line of recording thermometers.

The new line presents new problems to sales, production and finance departments. Prospect lists must be revised with the new products in mind; new sales stories must sing the praise of the new line; perhaps additional sales force will have to be recruited and trained to give the new line effective representation.

The engineering department will have to prepare new formulas or designs. The factory will have to buy new tools, dies and fixtures and possibly new machinery; radical changes may be necessary and credit policies may need revising, as the new line is sold to new types of customers.

Both the importance and inter-departmental character of the change make it a subject for consideration by the Board of Directors. After the new product decision is made, all departments will have to revise their policies to conform.

Most organisations provide parameters within which decision must be made. Human resource policies may prohibit gift from suppliers; pricing policies may permit regional sales managers to meet the lowest prices of competitors.

Need for Policy in Management:

Policies act as general guides to managerial decision-making; they delimit the areas within which decisions must be made and give indications of appropriate routes to the attainment of the objectives. They are usually the results of the top management’s formal deliberations, but they may result also from informal procedures, as where decisions acted on over long periods of time have crystallised into customary models of operation. Policies should allow for the exercise of discretion; for example, a decision by top management that its employees shall not perform any important work in their spare time for the firm’s competitors.

A policy of that type provides guidelines for middle managers, supervisors and others; it calls for the exercise of discretion in determining, for example, what is ‘spare time’, or who are the firm’s ‘competitors’.

Steiner has argued that policy/strategy responsibilities of top managers of an organisation are of equal, if not superior, importance to all other responsibilities. This point can be explained by looking at policy/strategy as a product of top management’s strategic planning process.

According to Peter Drucker the tasks that top managers perform are as follows:

Firstly, they formulate master policy/strategy. Secondly, they set standards, as for example the ‘conscience’ guides. Thirdly, it is their responsibility to build and maintain the human organisation. Fourthly, they have to maintain proper relationships with government, major suppliers, banks, other business, and so on. Fifthly, they have to perform various ‘ceremonial’ functions like attending seminars, conferences, etc. Finally, they must stand ready to lead when things go wrong. Drucker calls this a “stand-by organ for major crises”.

The task of top management is of a special nature. As Drucker put it: “The ideal top management is the one that does the things that are right and proper for its enterprise here and now.”

Primacy of Policy/Strategy:

Drucker has given the maximum priority to the policy/strategy function and has observed that the policy/strategy task influences and is influenced by the other functions. The significance of master policy/strategy can be realised from the following comment made by Robert E. Wood as the Chairman of a leading U. S. Company: “Business is like war in one respect; if its grand strategy is correct, any number of tactical errors can be made and yet the enterprise proves successful”. In fact, a company can be rather inefficient in its use of resources but can be successful if its grand strategy is right.”

In the words of Sterner: “Business success generally is not the happy result of one accidental brilliant strategy. Rather, success is the product of continuous attention to the changing environment and the insightful adaptations to it.”

Master policy/strategy is so important because it is formed as a part of the strategic planning process. All companies have grand policies/strategies. With respect to this, companies can be divided into two categories. First, there are those that live from day to day and whose policies/strategies are reactive to current events.

The second group consists of those who seek to anticipate the future and to prepare suitable guidelines for making better current decisions. The second group in its turn can be divided into two different types: those companies whose managers engage in the so-called intuitive anticipatory planning and those that do systematic formal planning.

To quote Steiner: “the outcome of both types of planning are similar in that they produce grand policy/strategy, which involves an understanding of the organisation’s environment and the formulation of basic missions, purposes, objectives and the policies and strategies to achieve the objectives. In the case of intuitive anticipatory planning, the results tend not to be written or are only sketchily written. The formal systems result in written sets of plans.”

Nowadays most modern companies have some sort of formal strategic planning system. There is hardly any need to emphasize that to a large extent the success of an enterprise will depend upon how well it formulates its policy/strategy in light of its evolving environment, how well it defines and articulates its policy/strategy and how well it ensures its implementation. We may now exercise the importance of policy/strategy in a modern enterprise (company).

Importance of Policy/Strategy:

There are various basic elements of the strategic planning process. These elements concern an understanding of the changing environment in which a company operates long range planning objectives, and programmes/policies and strategies.

These point may now be briefly discussed:

1. Reaction to environment:

The strategic planning process is invaluable to a company because it forces top management to be aware of its changing environment. In a dynamic world characterised by growing competition, rapid changes in tastes and preferences of buyers, technological change, etc., the environment of business may and does change very rapidly.

Such change opens up surprisingly new opportunities as well as presents frightening new threats. Failure to adjust to either can bring disaster. The strategic planning process not only focuses attention on opportunities and threats, but also raises certain fundamental questions the answers to which are of considerable importance to good management.

The questions that are likely arise in this context are:

(i) What are the weaknesses of our company?

(ii) What are our competitors doing and likely to do?

(iii) When will our present products require modification?

(iv) What is our cash flow?

(v) What are our capital needs?

(vi) Is our share of the market acceptable?

(vii) Are we moving in the right direction?

2. Defining company mission:

Secondly, strategic planning process addresses itself to defining the mission of the company. This includes the basic products and/or businesses of the company and the markets in which they are distributed. Stenier has suggested that an understanding of mission permits management to deal explicitly with a number of fundamental strategic issues such as the following: What is the competitive area in which we find ourselves? What are the requirements for success in this competitive environment? Is the size of the company quite optimum for achieving success? What are our relative strengths and weaknesses in our basic businesses? Is our basic mission appropriate in the light of our desires, capabilities, and opportunities?

The basic purposes refer to “fundamental aims the company seeks for such factors as product quality, customer service, response to community interests, and ethical conduct. These ends are usually broadly stated.” Most managers seek to set the technical standard that other companies in the industry will strive to meet.

In order to formulate purposes a manager has to effectively tackle such questions as: What emphasis will be placed on customer service? In what ways will we try to capture consumer confidence? What will be our ethical posture with respect to customers, suppliers, employees, government and creditors? The answers to such questions do have significant effects on business operations.

3. Formulation of long range objectives:

A third major element of strategic planning is the formulation of specific long range objectives. Such rough and ready statements as “our objective is to make a profit” do not provide proper direction for a company’s activities. There is need to quantify business objectives. For example, it is necessary to specify that the company’s objective is to achieve 10% return on net capital employed.

As Steiner has put it “In the strategic planning process, specific objectives are set for sales, profits, share of market, return on investment, and other factors that top management use to measure progress.”

4. The specification of programme policies and strategies:

Another component of strategic planning is “the specification of programme policies and strategies. These are the decisions concerning deployment of resources and guidelines developed to direct more detailed decisions in their implementation. They provide a framework within which managerial decisions throughout an enterprise can be made consistent with the basic missions, purposes, and objectives of the firm, as established by top management.”

In short, the overall significance of master policy/strategy is that “it addresses itself to the core responsibility of top management that is to ensure the success of the business today and tomorrow. To do this top management must be continuously involved in the process of surveying the environment, determining the nature of the business, setting goals for it, devising programme policies and strategies to achieve objectives, and assuring that actions take place in such a fashion that the policies and strategies chosen really do result in the achievement of objectives and basic company purposes.”

The strategic planning process provides “a unified framework within which managers can deal with the major issues managers should face, for dealing with major problems that are unique to the company, for identifying more easily new opportunities and for assessing strengths that can be capitalized upon and weaknesses that must be corrected.”

It can enable managers — without benefit of inspiration — to make solid contributions that would otherwise be lost. To conclude, however, the strategic planning process is a training ground for managers to be better managers because it forces thought processes that are essential to better management and raises and answers questions that good managers must address.

Strategic Management:

Strategic management is concerned primarily with relating the organisation to its environment, formulating strategies to adapt to that environment and assuring that implementation of strategies takes place.

The strategic planning process involves the following:

(1) Surveillance of the changing internal and external environment (in all its aspects),

(2) Identification in that environment of opportunities to exploit and dangers to avoid,

(3) Assessment of company strengths and weaknesses and their importance in formulation and evaluating strategies,

(4) Formulating missions and objectives,

(5) Identifying strategies to achieve company aims,

(6) Evaluating the strategies and choosing those which will be implemented, and

(7) Establishing and monitoring processes to make sure that strategies are properly implemented.

It may be noted that each of these processes contains many sub-processes.

In fact, strategic management involves establishing a framework to perform these various processes. Moreover, strategic management must embody all general management principles and practices devoted to strategy formulation and its implementation in the organisation.

Perhaps the most important feature of strategic management is that it focuses on top management strategic activities in contrast to more routine operational management. In the words of Steiner: “central to strategic management is the process of defining the strategic thrusts and directions of the business in light of the changing environment and devising strategies to achieve them.”

Since the external environment of business has become really complex in recent years and more and more companies have grown significantly in size and complexity, top managements find it necessary to spend more and more time on environmental forces and company relationship to them.

For large companies it is not enough to be efficient in operating the business. In addition, a strategy to adapt a company properly to its changing environment is key to its success.

It may be noted that strategic planning is not the same thing as strategic management. Strategic planning is a major aspect of strategic management. Indeed, it may be considered a central pillar of strategic management which involves more than planning per se. In short, “strategic management is a new perspective that highlights the significance, in both theory and practice, to a company of the need to pay more attention to environment and the formulation of strategies to relate to it.”

Procedures:

Procedures are guided to action that specifies in detail the manner in which activities are to be performed. They are narrower in scope than policies and are often intended to be used in implementing policies.

Procedures are a species of managerial planning. As such, they share with policies and organisational configuration the objectives and techniques of managerial planning. Procedures, in common with other forms of planning, seek to avoid the chaos of random activity by directing, coordinating and articulating the operations of an enterprise.

They help direct all enterprise activities toward common goals, they help impose consistency across the organisation and through time and they seek economy by enabling management to avoid the costs of recurrent investigation and to delegate authority to subordinates to make decisions within a framework of policies and procedures devised by the management.

Procedures emerge from the needs to establish chronological sequences of detailed instructions necessary for the successful carrying out of an activity. Assume that, in pursuance of Indian Airlines’ declared policy “carrying out effective servicing of incoming aircraft within a reasonable time of landing” management calls for the drawing up of appropriate procedures.

The resulting guides to action will state the sequence of activities (perhaps in the form of step-by-step routines) necessary to deal with the recurring events following the arrival of aircraft. A procedure is, by its nature, much narrower and more specific than a policy.

Policies vs. Procedures:

Policies are relatively general, reasonably permanent managerial plans. Procedures are less general but comparatively permanent. A policy maps out a field of action. It determines objectives and limits the area of action. Procedures are stipulated sequence of definite acts: Procedures mark a path through the area of policy. Procedures are not multidimensional; they do not cover areas of behaviour; they have only chronological sequence.

Procedures Implemented Policies:

Specific routings of salesmen embody a policy concerning territories within which sales shall be sought. Scheduling of work through the shop gives effect to policies regarding size of inventories and balancing of load factors.

In general, production planning procedures may, as a matter of policy, be used on estimated shipping requirements on stock limits, or on customer orders. Similarly, purchasing procedures may implement a policy of shopping the market for bargains or delimits an area of action, while procedures fix a path toward the objective or through the area. Sequence is the sine qua non of procedure.

Procedures are often utilised when degrees of accuracy in performance are needed if policies are to be executed effectively. But they can become mere routine or customary practice, and it is important, therefore, that they be revised and revised at regular intervals.

Rules (and Regulations):

Rules are the simplest type of standing plan. They are statements that a specific action must or must not be taken in a given situation. They act as substitutes to thinking and decision making and thus serve as guides to behaviour.

Rules state specific actions for particular situations. In a sense, they are guides to ‘acceptable behaviour’. Because their application precludes a discussion of alternatives, they allow for no discretion to be exercised.

Most Organisations use a Wide Variety of Rules:

Certain rules require employees to wear protective head coverings and safety shoes in construction sites. The rule has affinity with the procedure in that both are guides to specific types of action. It has no direct linkage to the policy which essentially guides decision-making.

A related point may be noted in this context:

“Although procedures may incorporate rules, rules do not incorporate procedures. Rules, unlike procedures, do not specify a time sequence. They permit no deviation from a stated course of action, and the manager’s discretion is limited to deciding whether or not to apply a rule in a given situation.”

Category # 3. The Scope or Breadth Dimension in Planning:

An alternative method of categorizing plans is by scope or breadth. Some business plans are very broad and long range, focusing upon key organisational objectives. Other types of plans specify how the organisation will mobilise itself to accomplish these objectives. It is in this context that we draw a distinction between strategic plans and tactical plans.

Strategic Planning:

The implementation of an organisation’s objectives is known as strategic planning. It can be defined as “true process of determining the major objectives of an organisation and the adoption of resources necessary to achieve those objectives.”

In any organisation, strategic planning occurs in two phases:

1. Deciding on the products to produce and /or the services to render.

2. Deciding on the marketing and/or manufacturing methods to employ.

That is, deciding on the best way to get the intended product and/or service to the proper audience.

Merging from strategic planning is often referred to as an organisation’s policies, and strategic planning is often referred to as setting policy. Strategic planning “provides the organisation with overall long-range direction and leads to the development of more specific plans, budgets, and policies.”

It forms the basis of such fundamental management decisions as:

Phase One Strategy:

In deciding on the products to produce or the services to render, there are several strategies that the chairman (president) of Godrej could follow. The company could specialise in office furniture. It could specialize in appliances, or it could employ any one of a number of other products and/or service strategies.

After careful consideration of the various strategies available, a decision has been made to sell only home furnishings, including appliances. For one reason or another, the president has decided not to produce and sell office furniture.

Phase Two Strategy:

Having decided to concentrate on home furnishings, the President of Godrej is now faced with a second strategy decision. Some furniture companies handle only the highest quality home furnishings, thereby striving to maintain the image of ‘quality’ dealer. Mark-ups are usually quite high, value is quite low, and promotional efforts are directed toward very small segment of the public.

The rival firms operate ‘volume’ outlets. They try to keep markups relatively low, with the expectation that overall profits will be raised by a larger sales volume. Still other dealers may follow different strategies. The selection of a particular strategy is simply a matter of managerial judgement; some companies make a profit by following one strategy, while other companies are equally profitable by following another. In the case in hand, Godrej has decided to operate ‘volume’ outlets, and to focus on maintaining a ‘discount image’.

Every organisation must make similar strategy decisions:

The set of strategies resulting from these decisions may not be written down, but they exist nonetheless and are a central guiding force in the organisation’s activities and its need for accounting information.

Tactical Planning:

Just as strategic planning focuses upon what the organisation will be in the future, tactical planning emphasises how this will be accomplished. The term ‘tactics’ refers to detailed plans and approaches to the implementation of decisions and the best way of achieving results.

Likewise, tactical planning refers to the implementation of activities and the allocation of resources necessary to achieve organisational objectives. In most cases strategic planning typically focus upon short-term implementation of activities and resource allocations.

The strategic planning process is the key to the long-term success of an organisation.

Table 5.5 shows the three bases for classifying planning: