After reading this article you will learn about:- 1. Narrow Span versus Wide Span 2. Graicunas Formula 3. Operative Span versus Executive Span 4. Tall versus Flat Organisations 5. Optimum Span 6. Effect on Organisational Levels of Varying the Span 7. Reasons for using a Wider Span 8. Reasons for using a Narrower Span and Other Details.

Contents:

- Narrow Span versus Wide Span

- Graicunas Formula

- Operative Span versus Executive Span

- Tall versus Flat Organisations

- Optimum Span

- Effect on Organisational Levels of Varying the Span

- Reasons for using a Wider Span

- Reasons for using a Narrower Span

1. Narrow Span versus Wide Span:

What should be the optimal span of management? Should it be relatively narrow (with few subordinates per manager) or relatively wide (many subordinates)? What is the optimal number of subordinates that a manager can deal with?

(1) The generally accepted rule is that the more complex a subordinates’ job, the fewer should be that manager’s number of subordinates.

(2) The second rule is that the more routine the work of subordinates, the larger the number of subordinates that can be effectively directed and controlled. When these two rules are applied, it is always found that organisations have narrow spans at their top and wider spans at lower levels.

The higher up one proceeds in the hierarchy of the organisation, the fewer will be his or her subordinates. In any case, there is a limit to the number of subordinates a manager can effectively supervise.

2. Graicunas Formula:

Long ago, A. V. Graicunas, a French consultant, attempted to quantify problems concerned with the span of management. He observed that a manager has to deal with three kinds of interaction with and among subordinates: direct (the manager’s one-to-one relationship with each subordinate), and groups (between groups of subordinates).

The number of possible interactions of all types between a manager and subordinates can be determined by using the following formula:

where, R = total number of interactions with and among subordinates and N = number of subordinates.

If a manager has 2 subordinates, 6 possible interactions exist. If the number of subordinates increases to 3, the number of possible interactions is 18; with 5 subordinates there are 100 possible interactions.

Graicunas’s formula offers no prescription for what N should be. But it does demonstrate how complex the relationships can become when there are more and more subordinates. The basic point to note here is that, as the span of management increases, each additional subordinate adds more complexity than the previous one did. For instance, increasing the number of subordinates from 9 to 10 is completely different from increasing the number from 3 to 4.

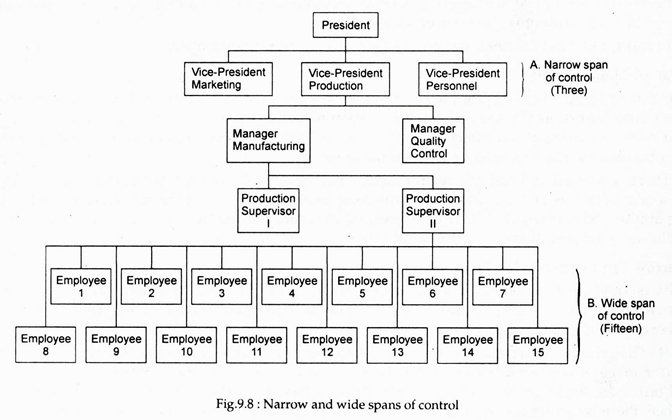

In Fig. 9.8 we illustrate narrow and wide spans of management. It is quite possible for a factory production supervisor to have 15 or more subordinates. It is because the subordinates who are well trained to follow directions and routines will, once they master their tasks, not demand much of their supervisor’s time and energies.

They will know what they have to accomplish and exactly how to accomplish it to meet their performance standards.

On the contrary, there is hardly any instance of a corporate vice-president with more than 3 or 4 subordinates. It is because the middle and upper management employees do very little routine jobs. These jobs usually require ingenuity and creativity and their tasks are non-repetitive in nature.

Since the problems are more complex, solutions are also difficult. Managers at these levels require more time to plan and organise their efforts properly. When they approach their bosses for assistance and direction, the boss need to have the time available to tender the assistance required.

This explains why, in general, the higher one goes in an organisation’s hierarchy, the narrower will be the span of control. The converse is also true: the lower one goes in the hierarchy, the more subordinates a manager will have.

3. Operative Span versus Executive Span:

Ralph C. Davis, however, described two kinds of spans: an operative span for lower-level managers and an executive span for middle and top managers. He suggested that while operative spans can approach 30 subordinates, executive spans should be limited to a minimum of 3 and a maximum of 9 subordinates (depending on the nature of the manager’s job, growth rate of the company, and similar factors).

Lyndall F. Urwick suggested that an executive span should under no circumstances exceed 6 subordinates.

P.F. Drucker has first recognised that the span of management is a crucial factor in structuring organisations and there is no hard-and-fast rule for an optimal span. However, before proceeding further, we may answer two important questions related to the span of management, viz.,

(1) how the span of management affects the overall structure of an organisation? and

(2) what are the most important variables that influence the appropriate span of management in a particular situation.

4. Tall Versus Flat Organisations:

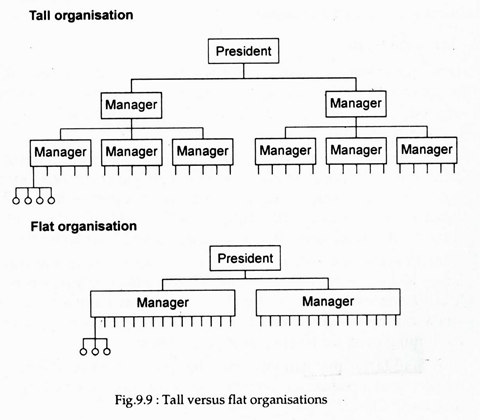

Let us think of an organisation consisting of 36 operating employees and a maximum span of management of 6. As shown in the top of Fig. 9.9, the result is a relatively tall organisation with 6 lower-level managers, 2 middle managers coordinating the lower-level managers, and a single top manage. With a wider span of control, however, the organisation shown in Fig. 9.9 becomes more flexible.

Here, the span is 18, with 2 managers supervising the same 36 employees and reporting to the president. The wider span eliminates the level of managerial positions and brings about a relatively ‘flat’ organisation structure.

Advantages and Disadvantages:

Research has indicated that a relatively flat organisation structure leads to higher levels of employee morale and productivity. Furthermore, a tall structure is more expensive (due to the larger number of managers involved) and that it creators more communication problems (due to the increased number of people whom vertical information must pass through).

On the other hand, a wide span of management in a flat organisation may result in a manager having more administrative responsibility (because there are fewer managers) and more supervisory responsibility (because there are more subordinates reporting to each manager). As and when these additional responsibilities become excessive, the flat organisation may suffer.

Just how many subordinates should a manager have depends on a host of factors and this has to be determined with a specific manager or job in mind.

The relevant issues here are the following:

a. How much is the organisation asking this manager to control?

b. How are the tasks to be divided?

c. What are the resources — men, money and time — available?

If a manager has too many subordinates to supervise, his (her) subordinates will be frustrated by their inability to obtain necessary assistance from him immediately. They will also remain depressed because of their lack of access to their boss as and when necessary. There could be wastage of time and other resources. Moreover plans, decisions and actions might be delayed or made without proper controls or safeguards.

On the contrary, if a manager has too few people to supervise, same undesirable consequences may follow. The manager’s subordinates might be either overworked or over supervised and could became frustrated and dissatisfied.

5. Optimum Span:

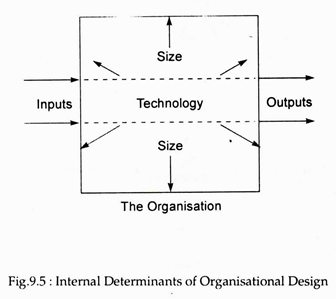

Thus, the optimum span of management depends on several variables such as the size of the organisation, technology, specialisation, and routines of activities.

In general, the optimum span depends on the supervisor’s “burden”- the greater the burden, the smaller the span, the less the burden, the greater the span.

In this context we may note that no two managers are equal in their skills, abilities or efficiencies. Thus a capable manager can supervise 6 people effectively, another manager in the same job may not be able to manage 2 people properly. But part of this difference is due to the fact that their subordinates will have differing capabilities and levels of experience as well.

Thus it is important to consider the qualifications of the managers and their subordinates when creating spans of control.

As Plunkett and Attner rightly put it:

“The more capable and experienced the sub-ordinates, the larger is the number of subordinates can be effectively supervised by one competent manager. The less time needed to train and acclimate, the more there is to devote to producing output. In general, spans can be widened with the growth in experience and competency of personnel — thus the continuing need for training and development.”

A final factor that can influence the span of control of a manager is the company’s philosophy toward centralisation or decentralisation in decision-making.

6. Effect on Organisational Levels of Varying the Span:

It may be noted at this stage that varying the spans of management influences the organisation structure. This point is illustrated in Fig.9.5 earlier. In example A, the manager has a very wide span of 128 subordinates. But, in practice, it would be virtually impossible for a single individual to manage such a large group without additional managerial assistance.

Now we may consider a situation where it is decided to reduce the span to four only. Four new positions of vice-presidents are created and managers are selected to fill the positions as shown in example B. Now the organisation is having 5 managers in total. So the span of the president is reduced to only four and that of each vice-president is now 32.

Finally, the president decides to reduce the span of each vice-president from 32 to 4, as shown in example C. This is achieved by creating 16 new department head positions and selecting the same number of managers to fill the positions. Now the span of each departmental head is 8.

If we follow the above examples closely we discover that one distinct pattern is emerging: as the span of management decreased, the percentage of required managerial positions increased, along with the number of hierarchical levels.

Thus organisations with increasing numbers of employees are left with three alternative options:

1. Increasing managerial spans.

2. Increasing levels of hierarchy.

3. Increasing both managerial spans and levels of hierarchy in some combination.

7. Reasons for using a Wider Span:

There are three basic reasons for using wider spans. Firstly, hierarchical levels tend to reduce the timeliness of information circulated from top to bottom of the organisation. Secondly, the larger the number of levels through which information has to pass, the greater the chance of distortion. Finally, adding levels is expensive in that it requires additional managerial compensation.

Since having too small a span results in the inefficient use of the manager’s resources, organisations do not make any hasty decision to add levels. Rather, they prefer to have wider spans and fewer levels for the reasons put forward above.

Of course, at some stage of organisational development the strains of increasingly large managerial span ultimately cause managerial inefficiency and require a move to additional hierarchical levels.

8. Reasons for using a Narrower Span:

If the span of management is too broad managers will not be left with much to do with the productive activities that make their organisation successful.

In same organisations a narrow span results from reducing the work force at lower levels while retaining managers (supervisors).

If the span of management is too broad, a manager has hardly any opportunity to devote personal attention to individual subordinates. In such a situation subordinates are unlikely to have close contact with their supervisors who are always busy in their own sphere of activities.

This may make subordinates feel insecure. On the contrary, if the manager spends too much time interacting with subordinates in order to maintain a personal approach, he (or she) will have little opportunity to plan.

9. Using Different Spans at Different Levels:

The span should not be the same throughout the organisation. Instead, the span may vary widely. As a general rule, the span gradually becomes narrow and narrow as one move from the bottom to the top of the organisation. Empirical studies have shown that in most representative organisations one finds a span of 5 to 12 executives reporting to the chief executive officer.

As the first line supervisory level, spans are much broader, commonly exceeding 30-40 subordinates when the work is routine, repetitive, unskilled, standardised and manual.

Spans, Levels and Employee Satisfaction:

Our study of the effect of hierarchical levels on employee satisfaction reveals at least two important points:

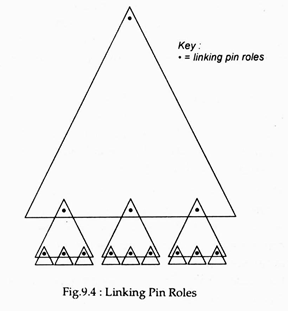

1. Employees at higher levels or organisations are more satisfied than employees at lower levels.

2. Higher-level managers in tall, steep organisational structures (see Fig. 9.4) are more satisfied than higher-level managers in flat organisational structures. On the contrary, lower-level managers in flat organisational structures are more satisfied than lower level managers in tall ones.

10. Factors Affecting Appropriate Span:

There is no magic formula for determining the appropriate span of management for particular situation. But the contingency approach developed by a group from Lockheed asserts that span size varies depending upon the particular situation.

According to this approach the following factors affect the span of management:

1. Similarity of functions: the greater the degree of similarity of the functions performed by the work group, the larger the span.

2. Geographical proximity: the closer the physical location of a work group, the larger the span.

3. Complexity of functions: the simpler and more repetitive the work functions performed by subordinates, the larger the span.

4. Degree of direct supervision required: the less the degree of direct supervision required, the larger the span.

5. Degree of supervisory co-ordination required: the less the degree of co-ordination required, the larger the span.

6. Planning required of the manager: the less the quantum of planning required, the larger the span.

7. Organisational assistance available to the supervisor: the more assistance the supervisor receives in functions such as braining, recruiting, and quality inspection, the larger the span.

Conclusion:

In some organisational settings, other factors are likely to influence the optimal span of management. Moreover, the relative importance of each factor varies in different settings. It is of strategic importance for the manager to assess the relative weight of each factor or set of factors when deciding what the optimal span of management is for his (her) unique situation.