After reading this article you will learn about:- 1. Introduction to Strategic Planning and Management 2. Definition and Importance of Strategy 3. Meaning of Strategic Planning 4. Focus of Strategic Planning 5. Strategy Formulation 6. Levels of Strategy 7. Strategy Implementation 8. Steps in the Strategic Planning Process 9. Strategic Management.

Contents:

- Introduction to Strategic Planning and Management

- Definition and Importance of Strategy

- Meaning of Strategic Planning

- Focus of Strategic Planning

- Strategy Formulation

- Levels of Strategy

- Strategy Implementation

- Steps in the Strategic Planning Process

- Strategic Management

1. Introduction to Strategic Planning and Management:

Business is like a war in one respect. If its grand strategy is correct, any number of tactical errors can be made and yet the enterprises prove successful. – Robert E.Wood

No plan can prevent a stupid person from doing the wrong thing in the wrong place at the wrong time — but a good plan should keep a concentration from forming. – C.E. Wilson

Planning is one of the most complex and difficult intellectual activities in which men can engage. Not to do it well is not a sin, but to settle for doing it less than well is. – R.L. Ackoff

Strategic Planning and Tactical Planning:

It has to be noted at the outset that strategic planning follows the development of organisational goals. It outlines the methods the organisation has chosen to identify and fulfill its mission(s). Strategy may be defined as “the pattern of the organisation’s goals and the major policies and plans it has for achieving these goals, stated in a way that defines what business the company is in or wants to be and the kind of company it is or wants to be”. Strategic planning, then, is an essentially the process of developing strategies.

There are four important elements of strategic planning:

1. Firstly, it focuses on matching the resources and skills of the organisation with the opportunities and risks present in the external environment.

2. Secondly, it is performed by managers at the top level.

3. Thirdly, it has a long-range perspective.

4. Fourthly, it is expressed in general and not in specific terms.

The other basic approach, quite different from the strategic, planning, is tactical planning. This is characterised by the development of specific tactics for achieving short-run objectives, the involvement of middle-level managers, and a high level of detail and specificity.

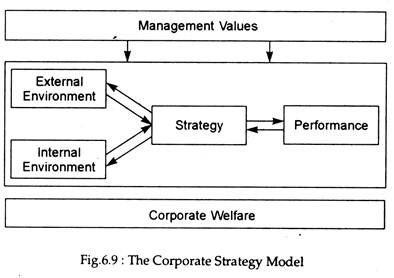

Fig. 6.1 illustrates the general relationship between these two types of planning. While strategic planning takes place at high levels in the organisation and has an extended time horizon, tactical plans are developed at the middle levels of the organisation, take a shorter-term perspective, and flow from the overall strategic plan.

Planning, in the broadest sense, refers to deciding in advance what one intends to do and how one intends to do it. It is not just a business activity. It has its roots in military operations. To quote the military theorist and historian, Liddell Hart, ‘strategy depends for success, first and most, on a sound calculation and co-ordination of the ends and the means’.

This article is concerned with the development of long-term or strategic planning as opposed to short-term operational planning. The essential difference between a ‘strategy’ and a ‘plan’ is that while the former is a broad statement of objectives and the policy for achieving them, the latter is a more detailed and quantitative statement of both the objectives and means.

A plan is the first step in implementing the strategy. The importance of this distinction is that the broad strategy of the enterprise should need less frequent revision than its more detailed long-term plans. For example, the strategy may be to acquire manufacturing facilities in an area’; the plan would be concerned with their capacity, location, timing, costs, etc.

The strategy usually remains valid for years together. Unless it does it will prove disastrous. But there is a continuous need to revise detailed plans as demand forecasts, production costs and so on evolve. In general, the formulation or reformulation of strategy need not, or does-not take place at regular intervals; it depends on how rapidly the situation changes. On the contrary, the preparation of plans should, to the maximum extent possible, be one of the management activities conducted on a regular basis.

2. Definition and Importance of Strategy:

The concept of corporate strategy is analogous to that war. Strategy in an area of management is “concerned with the general direction and long-term policy of the business as distinct from short- term policy of the business and may be defined as its long-term objectives and the general means by which it intends to achieve them.”

Strategic decisions are, by definition, of such importance that they affect the future of the organisation as a whole. Yet they may be primarily concerned with particular dimensions or aspects of the business. For example, the post-war decision of U. K.’s Marks and Spencer to enter food retailing was concerned with their product range.

Their second major initiative — opening a store in Paris — was concerned with their geographical market. Such decisions about products and markets are of paramount importance to business firms.

In business firms, strategic decisions are concerned with such critical issues as breadth of product line, geographical scope, industry position, extent of Vertical integration, and orientation towards growth, Strategic writers, treats strategy as almost exclusively concerned with the relationship between the firm and its environment and, hence, with the selection of the products it produces and the market in which it sells those products.

Thus by strategic decision making, top management determines the position of the firm relative to its environment. At any given time, the firm’s orientation to the environment may be described as its strategic posture. Changes in this posture require redeployment of the firm’s assets into new configurations. Strategic decisions express the firm’s basic purposes and the direction it wishes to take in relation to the society of which it is a part.

There are, however, other potentially important areas of strategic concern. For example, there was British Leyland’s strategic decision to link up with Honda. This decision was not only concerned with product/market mix, but it had also major implications for production and development policy (such as the use of Japanese components and know-how, and buying in a fully developed design). This particular move threw open the whole of B L’s future production and model development strategies.

Basically strategic issues are complex than tactical and other issues largely because they are of a long-term nature. This explains why Alfred Chandler preferred to suggest a broader definition of the concept. His definition was largely based on a study of the growth of the multi-divisional from of organisation in large U.S. corporations in response to strategic change.

He defined strategy as “the determination of the basic long-term goals and objectives of an enterprise, and the adoption of courses of action and the allocation of resources necessary for carrying out these goals.”

In a competitive industry, a particular firm formulates its basic strategy to position itself relative to the market and competitors. The importance of strategic choices is clear. Good strategy will provide an opportunity for survival and growth. Poor strategy will doom a firm to decline, deterioration, and eventual death.

To H. I. Ansoff and others, strategy covers all aspects of the relationship between the firm and its environment, rather than just the product/market mix, and thus permits a great variety of issues to be treated as strategic. For example, Hofer and Schendel define strategy as ‘the basic characteristics of the match an organisation achieves with its environment.’

This approach provides scope for considering the supply aspects of a firm’s relationship with its environment, but it fails to recognise explicitly major strategic issues that can arise within a firm such as its manpower and production policies.

Finally Andrews has made the point that a firm’s strategy may be implicit rather than explicit. He has suggested the following definition of strategy which seems to be the most comprehensive of all:

Corporate strategy is the pattern of decisions in a company that determines and reveals its objectives, purposes, or goals, products and principal policies and plans for achieving those goals, and defines the range of business the company is to pursue, the kind of economic and human organisation it is, or intends to be, and the nature of the economic and non-economic contribution it intends to make to its shareholders, employees, customers and communities.

3. Meaning of Strategic Planning:

Strategic planning is defined as “the process of determining the major objectives of an organisation and then adopting the courses of,action and allocating the resources necessary to achieve those objectives.” It is the process that includes “a set of interactive and overlapping decisions leading to the development of an effective strategy for a firm.”

According to W. F. Glueck and N.H Synder, the process includes the following:

(1) The determination of the firm’s mission;

(2) The selection of goals or objectives the firm wishes to pursue;

(3) The formulation of opportunities and threats arising out of the firm’s external environment;

(4) An assessment of the internal strengths and weaknesses of the firm;

(5) The identification of feasible strategic alternatives available to the firm;

(6) The choice of an alternative (s) the firm wishes to pursue;

(7) The development of an operational plan to facilitate achievement of the firm’s objectives; and

(8) The design of a control or feedback system to monitor the firm’s performance while the strategic plan is being implemented.

Advantages:

Managers undertake strategic planning for a number of reasons:

1. First, there is a feeling among most managers that strategic planning will increase organisational effectiveness.

2. Secondly, the strategic planning process itself promotes feelings of accomplishment and satisfaction. As manager and planners work together to formulate strategy and implementation plans, they develop confidence in their situation. This may be a source of gratification and satisfaction for managers.

3. Thirdly, strategic planning facilitates adaptation to change.

4. – Fourthly, strategic planning is a process through which the efforts of divisions, functions and individuals can be co-ordinated.

5. Fifthly, when there is a major change or reorganisation in top management strategic planning can help to educate the new top management team about the internal and external opportunities and constraints the team members face.

6. Finally, when the performance of an organisation is not quite satisfactory strategic planning may be undertaken to identify the problems and solutions.

Boone and Koontz have opined that “strategic plans provide the organisation with long-range direction. They focus on relatively uncontrollable environmental factors that affect the achievement of organisational objectives.”

Furthermore D.E. Schendel and C. W. Hofer have pointed out that “although strategic planning is generally associated with long-range planning, it is also involved in such short- and intermediate-range questions as whether to merge with another organisation or to broaden activities from a domestic to an international market.”

Strategic Planning vs. Tactical Planning:

The end result of strategic planning is “to provide the organisation with an overall context for the development of more specific plans, policies, forecasts and budgets.” Strategic planning focuses upon what the organisation will achieve if all key managerial functions be carried out with a view to accomplishing organisational goals.

But, tactical planning is concerned with current and future activities, focusing upon the effective allocation of resources to assure their implementation. Just as wars in general are guided by strategic planning, a single battle may be won (or lost) due to tactical planning.

A related point may be noted in this context. Although the two types of planning are different, there is need to integrate the two into one over-all system with a view to accomplishing organisational objectives. The development of tactics is largely based on strategic plans. Recent studies have revealed that by reviewing and adjusting plans annually, decision makers can keep both strategic and tactical plans sufficiently flexible, thus permitting their adjustment to changing environmental factors while maintaining their focus upon organisational objectives.

4. Focus of Strategic Planning:

To be able to understand strategic planning, we must understand the focus of strategy which, in its turn, is determined by at least three things:

(1) Its components,

(2) The distinction between strategy formulation and strategy implementation, and

(3) Its level.

Components of Strategy:

There should be four basic components of a well-conceived strategy, viz., scope, resource deployment, competitive advantages and synergy.

1. Scope:

The scope of a strategy also known as the statement of the organisation’s domain, specifies the present and planned interactions between the organisation and its external environment. The scope specifies what markets the organisation expects to compete in. For example, Philips India focuses on the electronics industry and its sub-markets (such as consumer electronics, semiconductors, and so forth) but does not produce fast food or commercial vehicles.

2. Resource Deployment:

The strategy should also give a broad outline of how its resources will be distributed across various areas. It indicates both current and future (projected) resource deployment. A highly diversified company normally develops new (potentially profitable) products and drops old (unprofitable) products for improving the pattern of resource allocation and for achieving both effectiveness and efficiency.

This means that resources will be diverted from less profitable to more profitable lines of business. Resource deployment is an aspect of a company’s resource deployment policy.

3. Competitive Advantages:

Michael Porter, the Harvard strategist, has pointed out that the strategy should specify the competitive advantages that result from the organisation’s scope and pattern of resource deployment. A company will always try to deploy its resources in such a fashion that it is able to capitalise on the competitive advantages it has built over the years.

4. Synergy:

Strategy should also take note of the synergic effect that is likely to be generated from decisions about scope, resource deployment and competitive advantages. Synergy is an important aspect of strategy.

Strategy Formulation and Implementation:

Ansoff has pointed out that in order to understand the focus of strategic planning, it is necessary to draw a distinction between strategy formulation and strategy implementation. While the former is “the set of processes involved in creating or determining the strategy of the organisation, the latter refers to the methods by which strategies are operationalised or executed within the organisation. While the formulation stage determines what the strategy is, the implementation stage focuses on how it will be achieved.

5. Strategy Formulation:

According to R.W. Griffin, strategy formulation is the set of processes involved in creating or determining an organisation’s strategy.

This set of processes consists of the following four steps:

1. Strategic goals:

The first step in formulating strategy is to set strategic goals for the organisation. Such goals are the broadest goals established at the organisational level and serve to guide the overall fortunes of the organisation. The organisation may also have various strategic goals and these goals might change over time.

2. Environmental analysis:

In the next stage, the organisation conducts what Michael E. Porter calls an environmental analysis. This analysis involves looking very closely and carefully at the task environment in order to ascertain the primary opportunities available to the organisation, as well as its major threats.

Porter’s approach to environment analysis or his framework of analysis identifies the following five competitive forces:

(i) Threat of New Entrants:

This refers to the extent to which new competitors can easily enter a particular market or market segment. For example, it is fairly easy to enter the fast food market. But it is very costly and, at the same time, extremely difficult to join the automobile industry, due to huge capital requirement in plant, equipment, materials and distribution systems.

(ii) Jockeying among Contestants:

This new term is used to refer to the competitive relationship between dominant firms in the industry. In oligopolistic industries like fast food or soft drink firms often engage in intensive price wars, competitive advertising and new product introduction.

(iii) Threat of Substitute Products:

This refers to the extent to which alternative products or services may supplement or reduce the need for existing or even well-established products or services. Microcomputers, for example, eliminates the need for typewriters, large mainframe computers and even calculators.

(iv) Power of Buyers:

This refers to the extent to which buyers of the products or services in an industry have the ability to influence the suppliers. In case of high value items like aircraft, such as American Airlines, United Airlines or KLM or JAL have considerable influence over the price they are willing to pay, the delivery date of the order and so forth.

(v) Power of Suppliers:

This indicates the extent to which suppliers have the ability to influence potential buyers. Large oligopolistic firms can exert some influence over their buyers.

3. Organisational Analysis:

This phase of strategy formulation involves a detailed diagnosis of the strengths and weaknesses of the organisation.

According to H.W. Henry, this analysis has to be as detailed and thorough as possible and should include at least the following six areas of an organisation:

(i) Human resources (quality and quantity of appropriate managerial personnel, etc.)

(ii) Physical resources (plant and equipment, office space, etc.)

(iii) Financial resources (cash, assets, lines of credit, debt, etc.)

(iv) Information resources (quality and quantity of available information about competitors, etc.)

(v) Market position (market share, strength of product line, etc.)

(vi) Research and development efforts (quality and quantity breakthroughs expected from R&D efforts, etc.)

While a major portion of such information is readily available from an organisation management information system as a matter of routine, other types of information can be obtained specifically for the strategy-formulation process. No doubt, efforts needed to gather the necessary data will be a good investment.

Matching Organisations and Environments:

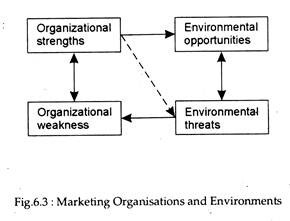

After establishing strategic goals and completing environmental and organisational analyses, the organisation moves to the final stage of strategy formulation. In this step, it has to match the strengths and weaknesses of the organisation with the corresponding opportunities presented and threats posed by the external environment. Fig. 6.3 shows how an organisation matches itself with its environmental opportunities and threats.

As a general rule, the basic purpose of this exercise is “to align the organisation with its environment in such a way as to take advantage of opportunities in the environment and avoid threats through the recognition of internal strengths and weaknesses”.

The framework presented in Fig. 6.3 suggests several specific relationships of considerable interest to managers and strategists. Prima facie, organisational strengths and weaknesses and environmental opportunities and threats are usually interrelated. Secondly, organisational strengths should generally be targeted toward environmental opportunities.

Thirdly, the organisation should recognise that its weaknesses are particularly valuable to environmental threats.

Finally, to the extent possible, the firm might also use its strengths to offset environmental threats, at least partly. This action uses an organisational strength (say, surplus funds) to constrain an environmental threat (strong power of suppliers).

6. Levels of Strategy:

Finally, while focusing on strategy, it is necessary to draw a distinction among three different levels of strategy, viz., corporate strategy, business strategy and functional strategy.

1. Corporate strategy:

Corporate strategy, also called grand strategy by Harold Koontz, is the course charted for the total organisation. It seeks to specify what type(s) of business(es) the organisation intends to be in.

Hence, corporate strategy is primarily concerned with the scope and resource deployment components of strategy. Such decisions as to which new businesses to enter, which businesses to buy and perhaps, eventually, which business to sell is a corporate strategy.

2. Business strategy:

Business strategy formulation goes one step ahead of corporate strategy. It involves determining how best to compete in a particular market or industry whereas corporate strategy focuses on what businesses the company should be in. Business strategy is concerned with the strategies for each unit of business within the corporation. Business strategy focuses less on scope and resource deployment and more on competitive advantage and synergy.

3. Functional strategy:

Finally, a functional strategy is one developed for a major functional area such as production, finance or marketing within a particular business.

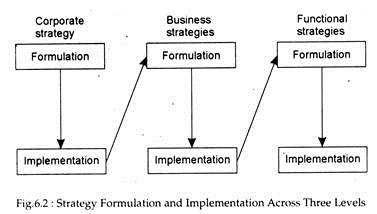

Fig. 6.2 illustrates the relationship between strategy formulation and implementation and the three levels of strategy. At a general level, the formulation implementation cycle starts at the corporate level, then follows systematically across the business and functional level.

This simple model is no doubt an abstraction in the sense that the process is more complex and dynamic in the real world of business, but serves to represent the general nature of the strategic planning process.

A. Corporate Strategy:

We have already noted that there are three basic levels at which these strategy-formulation activities occur: the corporate level, the business level and the functional level. The most dominant approach to corporate strategy is directed toward what is called the business portfolio matrix approach to strategy.

Business Portfolio Matrix:

Essentially this approach to corporate strategy, which first began at General Electric and was eventually developed into a complete framework by the Boston Consulting Group, consists of three clearly defined and specified phases: identification of strategic business units, classification of these units into a matrix and selection of alternative strategies for dealing with the units.

Using Strategic Business Units (SBU) Concept:

Most modern organisations make use of strategic business units (SBUs) in strategic planning. These are divisions composed of key businesses within multiproduct companies with specific managers, resources, objectives and competitors. Such units may encompass a division, a product line, or a single product.

The concept first originated in 1971 in the world’s one of the most diversified companies, viz., General Electric (USA). Executives and planners in GEC decided to base their strategic planning on viewing their organisation as a ‘portfolio’ of business. The company’s wine product group and 48 divisions were reorganised into 43 such SBUs.

One specific example of such, change may be of interest to us. Food preparation applications, for instance, which previously had been located in three separate divisions, were merged into a single S.B.U. serving the ‘housewives’ market. The idea was emulated and effectively adopted by various diversified organisations in the USA and other countries.

Generally, SBUs have the following characteristics:

1. Each SBU has its own mission.

2. Each is a single unit or set of related units.

3. Each has its own competitors.

4. Each can have its own unique strategy apart from that of other SBUs in the organisation.

The SBU concept illustrates the matrix form of organisational design. The basic concept is easy to understand: a conceptual matrix that relates SBUs to competitors and assesses the long-term product market attractiveness. Corporate and divisional planners in the GEC use such dimensions as segment size and SBU growth rate, market share, profitability, margins, technology position, strengths or weaknesses, image, environmental impact and management.

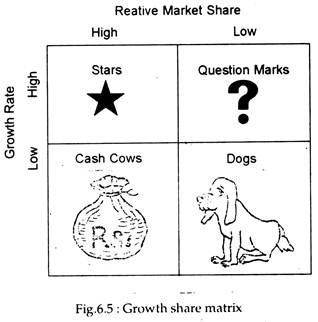

Essentially the portfolio matrix (also known as growth share matrix) categorises each SBU in terms of its rate of market growth and its relative share of the market. The object is to assist managers in allocating resources to each SBU. (At this stage, the resource deployment component of corporate strategy becomes relevant).

When market share and growth rate are each rated as either high or low, the 2 x 2 matrix shown in Fig. 6.5 emerges. We may now briefly discuss each of the four kinds of SBUs identified in the portfolio matrix.

Fig. 6.5 shows a typical matrix with labels for each cell. This is known as the growth-share matrix technique. It is an effective method to deal with corporate profit strategy and is widely used.

In Fig. 6.5 industry growth is measured on the vertical axis and relative market share of the firm on the horizontal axis. Relative market share is defined as the firm’s market share divided by the market share of its largest competitor in the industry. For instance, if a firm has a 15% market share and the largest competitor has a 20% share, this would produce a relative market share of 0.75—which falls in the low range of Fig.6.5.

The definitions of ‘high’ and ‘low’ for both industry growth relative market share are obviously arbitrary. Nevertheless, this simple four-quadrant device can be used by corporate planners to categories the cash flow prospect of each business unit in order to decide how to manage the corporate portfolio of assets. (Thus the growth-share matrix is, in essence, a technique of portfolio management). That is, relative market share is used as a measure of a business unit’s ability to generate cash inflows, and industry growth is used to measure the demand for cash (or cash outflows).

Dogs are products or businesses with both low market shares and poor growth prospects. No doubt they generate some funds for the firm. But their future prospects are poor. As a result most organisations attempt to withdraw these from their businesses or product lines as quickly as possible.

At other extreme are stars, which have large relative market share in a rapidly growing industry. Although they demand a high volume of cash in order to maintain their growth, they hold the potential of high profits. Thus, being high-growth market leaders, stars represent desirable investments for two reasons: their current competitive position and future potential.

The two remaining categories, cash cows and wild cards represent the essence of the portfolio strategy, which calls for ‘milking’ the excess cash flow from cash cows and using these funds to turn wild card into stars. The implication of this is easy to find; because cash cows have high relative market share in low-growth industries, they generate a large positive cash inflow that can be used to fund the cash requirements of wild cards.

In this evolutionary cycle, stars will eventually turn into cash cows as the industry matures and fall from high growth to low growth. It may be added that cash cows are products or businesses with both market share but low growth prospects. As a result they generate considerable inflows of funds for the firm.

Question marks are products or businesses with both high market shares in a high growth market. Due to the growing nature of the market, question marks typically require much more cash than they are able to generate. Such situations force the manager to take/accept/reject (a basic go/no go) decision. Unless the question marks can be converted into stars, the firm should pursue other alternatives.

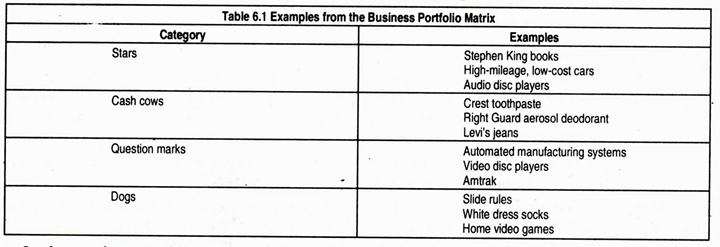

Several examples of stars, cast cows, question marks, and dogs are listed in Table 6.1.

In short, a firm would naturally prefer to have stars instead of dogs: In considering the deployment or redeployment of its resources in the four quadrants of the matrix, management might reason somehow as follows:

Stars:

(Large share of high-growth market). Inject additional money and attempt to gain an even larger share of the market.

Question Marks:

(Low share of fast-growth market). Consider fighting for more market share but recognize danger of getting into a ‘cash trap’.

Cows:

(High share of slow-growth market.) Milk the ‘cash cows’ – that is, remove money and reinvest in stars or possible question marks.

Dogs:

(Low share of slow-growth market.) Eliminate them.

The underlying idea holds that an increase in a company’s volume leads to reduction of production costs. This results, in turn, from the operation of what Bruce Henderson has termed the “experience curve”. Practice tends to make perfect, and production costs reportedly decline 20 to 30 percent in real terms whenever experience is doubled.

As a result of these forces, a company which increases its volume by expanding market share and/or by concentrating in fast growth markets may be able to increase its efficiency and profitability. Although this is only one of various analytical methods, it illustrates the systematic corporate evaluation of resources deployment.

Although such a simple growth/share matrix forces corporate strategists to consider the opportunity cost of a rupee earned by a cash cow and whether it would be better to invest it in the cash cow or the wild card. In the portfolio view of asset management, rupees earned by a cash cow and whether it would be better to invest it in the cash cow or the wild card. In the portfolio view of asset management, rupees earned in one quadrant are not necessarily reinvested in the same quadrant.

Instead, there is a constant reassessment of where the highest rate of return can be earned — rupee flowing away from quadrants with poor future profit prospects and toward quadrants with better future opportunities. In essence, the portfolio approach is based on incremental (marginal) revenue and incremental (marginal) cost considerations.

In developing strategic plans for handling the portfolio of SBUs, most proponents of this approach recommend the following:

Question marks must either get into the star category or get out of the portfolio. In the first case, they should take the move with carefully developed strategic plans so that major risk elements are identified and contained.

Stars are short-term cash consumers and are managed for long-term positions. Over the long-run, as their segment attractiveness ultimately declines, they will become cash cows, generating cash to support the next round of stars.

Selection of Strategy Mix:

After identifying SBUs and classifying them within the business portfolio matrix, the final stage of this strategic approach is to establish methods for managing each SBU. This means that a business strategy is developed for each SBU; the corporate strategy is also involved inasmuch as issues of resource deployment are important. Various alternative strategies can be adopted.

Growth Strategy:

A growth strategy is normally treated as appropriate for stars and for question marks that stand a reasonable chance of becoming stars in the future.

Maintenance Strategy:

For other SBUs a more appropriate strategy is to maintain a modest level of growth or simply to maintain the status quo. This has proved to be correct strategy for cash cows.

Retrenchment or Turnaround Strategy:

This strategy seems to be appropriate when a question mark fails to move into the star category, or when a cash cow begins to lose ground. In such situations the organisation may try to stimulate the market, or find new uses for its product, or to change its image in the eyes of its customers.

Disvestiture Strategy:

This is the appropriate strategy for some SBUs (especially those in the dog category). The organisation may sell the SBU or simply close down that particular product or service line.

The business portfolio matrix approach has gained popularity over the years. Recent scientific studies have also got considerable support to the validity of this approach. So, this approach to strategy is likely to remain popular in the future, too.

Intuitive Approach:

Another less popular model of corporate strategy is the intuitive model. This approach suggests that managers in an organisation must be able to develop an intuitive consensus, based on experience, values and organisational norms, as to exactly what path(s) the organisation should follow.

Such an approach is not normally a conscious decision but a shared acceptance that evolves gradually with the passage of time. Managers do something because they ‘feel right’. When they are successful, they try it again. Continued success with this intuitive style causes them to rely heavily on their intuition for future strategic planning.

B. Functional Strategy:

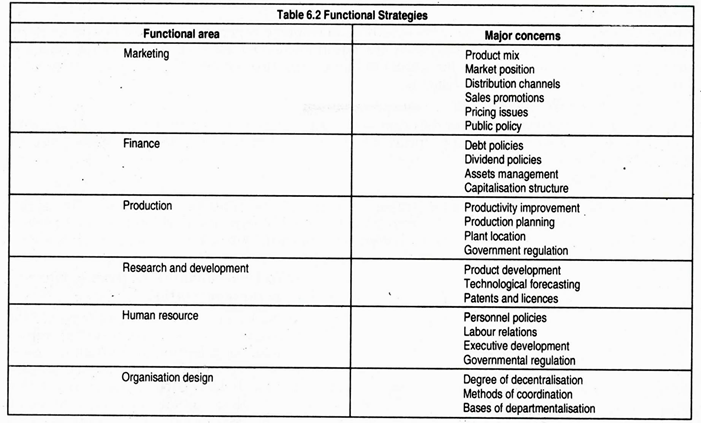

The third level of strategic planning is the creation of functional strategies. One such strategy can be formulated for each functional area of business, as illustrated in Table 6.2.

(i) Marketing strategy:

For most organisations, the marketing strategy is the most important functional strategy, and it usually reflects the overall strategy of the company. According to Peter Drucker: “Business has only two functions — innovation and marketing”.

The marketing strategy deals with a number of major issues confronting the organisation. One of these is the product mix. Other major issues in the marketing strategy include desired market position, distribution channels, sales, production (such as advertisement budget and the size of the sales force), pricing policies and public policy.

(ii) Financial Strategy:

Developing the right financial strategy is essential to an organisation. The most important aspect of this strategy is deciding on the most appropriate capital structure (which consists of an appropriate mix of debt and equity capital). Another element in financial strategy is debt policy: how much to borrow and in what form? Asset management focuses on the handling of current and long-term assets. Finally, dividend policy determines what proportion of earnings is distributed to shareholders and what proportion to retain for expansion and diversification.

(iii) Production Strategy:

Production strategy, which originates from its marketing strategy, focuses mainly on quality, with cost being assigned a secondary role. The methods for improving productivity are to be developed. Production planning (when to produce, how much to produce and how to produce) is especially important for manufacturers. Production strategy also .involves decisions about where to locate plants (or factories). Finally, it should take into consideration various government regulations.

(iv) Research and Development (R&D) Strategy:

Most growing organisations — particularly in knowledge-intensive industries like electronics — find it important to have a R&D strategy. A primary area of concern here is making decisions about product development.

(v) Human Resource Strategy:

This strategy needs to be developed because human resource is perhaps the most important input of an organisation. Human resources policies are required on such matters as compensation, selection and performance appraisal. Another aspect of human resource strategy is labour relations, especially negotiations with organised labour.

(vi) Organisation Design Strategy:

This strategy is concerned with how the organisation structures itself—how positions, departments and divisions are arranged. The appropriate design makes it more likely that the firm will successfully carry out its strategic plans.

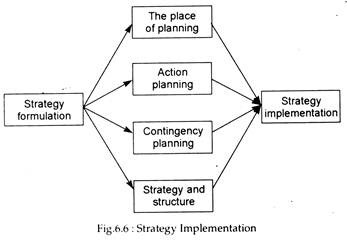

7. Strategy Implementation:

As noted earlier in this article, after strategy is formulated, it must be implemented. These two processes are no doubt different but interrelated because both are inherent (and distinct) parts of strategic planning. There are four major components of strategy implementation, which are summarised in Fig. 6.6.

(i) Understanding the place of planning in the organization:

First there is the need on the part of the organisation to recognise the importance of planning as both an on-going activity and an organisational subsystem. It has to be borne in mind that planning is not a stable, cross-sectional process, but a dynamic, continuous activity that pervades all parts of the organisation.

(ii) Action Planning:

In the next stage, there is need for action planning. It is the commitment to strategic planning. It represents short-term, day-to-day plans necessary to execute the Strategic plans of the organisation. Tactical plans, single-use plans and standing plans are all examples of action plans.

(iii) Contingency Planning:

In reality, plans do not always work out as intended. Contingency planning is necessary to overcome any disruptions that occur to planning premises due to external (environmental) changes. Since planning premises guide the original strategy in case of unexpected changes there is need for a change in the current strategy or the adoption of a completely new strategy. The essence of contingency planning is anticipating possible changes and developing responses to them.

(iv) Strategy and Structure:

The last element of strategy implementation is the recognition of the link that exists between that strategy and the structure of the organisation.

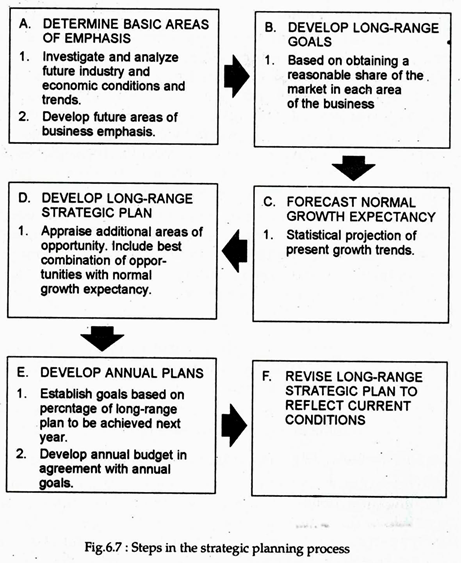

8. Steps in the Strategic Planning Process:

Strategic planning involves not only the development of organisational objectives but also specifications for how they will be accomplished. The development of strategic plans forces managers to broaden their concern from an exclusive focus on short-range matters to a detailed examination of various broad organisational issues. Various steps are involved in the strategic planning process.

The development of strategic plans forces managers to broaden their concern from an exclusive focus on short-range matters to a detailed examination of various broad organisational issues. Various steps are involved in the strategic planning process.

The following steps are most important:

1. First, there is need to determine the basic areas of emphasis for the organisation. With a view to determining the objectives and specific goals, the firm has to assess its mission. In the words of a renowned writer on management: “the mission of a business is the fundamental, unique purpose that sets it apart from other firms of its type and that identifies the scope of its operation in product and market terms. The mission is a general, enduring statement of company interest.”

Every enterprise expresses its mission in its own way. For example, the mission of a transportation system. Likewise, the mission of a private non-life insurance company may be “to provide security against an ever-increasing range of risks and hazards that threaten the financial welfare of individuals, families, groups and businesses at everyeconomic level that can be served by the private sector.”

2. Secondly, long-range goals have to be developed. It is to be noted that once the organisational goals follows as a consequence.

3. Thirdly, there is need to forecast the expected growth rate. Forecasting is a critical ingredient of the planning process. It refers to assessing the future normally using calculations and projections which take account of past performance, current trends and anticipated changes in the foreseeable period ahead. Corporate forecasting often requires use of statistical and mathematical methods such as moving averages, regression analysis and operations research.

4. Fourthly, a long-range strategic plan has to be formulated. Such a plan refers to the comprehensive plan of major actions by which a firm intends to accomplish its long-term goals.

5. Fifthly, there is need to develop annual plans. A few specific short-term plans originate from the broader long-range strategic plan.

6. Finally, the long-range plans must be periodically revised to reflect current conditions. This final step involves adapting plans to changed environmental and internal conditions. Fig. 6.7 illustrates the above steps.

The above sequence shows a systematic planning process in which short and long-term plans are integrated into an overall plan. The left hand side of the figure shows each major step included in the planning process. The right hand side illustrates the decision process for each step.

The strategic planning process is directed toward arriving at three basic questions:

1. Where is the company now?

2. Where does it want to be at a specified future date?

3. How will the company get there?

The answer to the first question is suggested on the basis of data on current operation. Information about the present financial status, current market share and relative strengths and members (human, financial and material) of the organisation is utilized to make an overall assessment of the organisation’s present position in relation to its objectives. The second question is answered on the basis of such assessment.

In addition, such assessment enables one to develop premises related to those objectives. Strategic plans are developed on the basis of forecasts of market growth, economic conditions, changes in political and legal conditions as also technological developments.

Finally, in order to answer the third question there is need to determine the activities necessary to achieve established goals.

It requires two things:

(a) An identification of resources necessary to implement the plan and

(b) The establishment of a monitoring system to review actual performance and inform management of the various possible adjustments that must be made in the plan.

9. Strategic Management:

In today’s highly competitive environment, all organisations face uncertain environments, since both product and technology life cycles are shortening relentlessly. Never has it been more important for businesses and their leaders to position their organisations strategically to compete successfully for the future.

This requires that managers thoroughly understand the dynamics of their industries, the trends in their external environment and the basic anatomy of their firms. They must also balance the multiple activities of the various functions in their organisations and galvanize them toward unified action.To accomplish all these activities simultaneously requires that managers engage in strategic management.

Strategic management encompasses the activities of senior-level executives in their attempt to influence the overall direction of their corporations. Strategic management is the primary function of line executive—the people on the firing line who deal with the real world of customers, machines, products and people.

The reason is easy to find out: the people closest to the action are in the best position to know what is going on in the business, what trends and tendencies are developing, and what competitors are doing. In other words, those who must execute corporate strategy must be involved in developing it.

In today’s world there should be a shift from the mentality of survival, meeting the budget, or merely forecasting the future, to one of creating the future by shaping one’s industry and markets rather than reacting to them.

A firm’s strategic managers must know and understand what the firm’s mission and strategy are. Second, they must know their core competencies and capabilities as an organisation. Third, they must be able to identify their competitors and predict their actions to the firm’s strategic moves. Fourth, they must develop a culture that supports the strategy. Finally, they must constantly be developing new capabilities for renaming their strategy and competing successfully in the future.

Elements of Strategy:

A company’s strategy has the following elements:

(i) A plan for the future,

(ii) Setting a goal and the steps to reach it,

(iii) A method of facing competition,

(iv) A mission,

(v) A path,

(vi) A set of integrated decisions, and

(vii) A battle plan.

What these components have in common is an orientation toward the future, a sense of deliberate action, and to some extent, a notion of competitive rivalry.

Difference between Strategic Management and Planning:

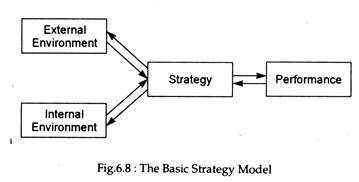

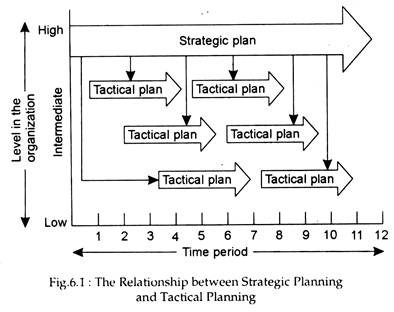

Strategic management differs from strategic planning. All strategic planning approaches attempt to find an optimal match between the resources and capabilities available within the firm (strengths and weaknesses) and the external market conditions and environmental trends (opportunities and threats). This match or co-alignment (often called a SWOT analysis) results in a strategy, whose efficiency translates into sound level of corporate performance. The basic dimensions of this simple approach are illustrated in the basic strategy model shown in Fig.6.8.

A key element in the basic strategy model is the reciprocal influence of all of the variables. The degree of success of an organisation would be manifested in some level of performance (arrow from strategy to performance) and, in turn, the performance level would serve as feedback, indicating that further adaptations of strategy might be in order (arrow from performance to strategy).

However, the model presented in Fig. 6.9 has to be modified and amplified to consider the implementation of strategy. Management needs to include the ‘soft’ sides of strategy, political feasibility and organisational acceptability. Thus, a complete model would include explicit consideration of management values and prevailing corporate culture, as shown in Fig. 6.9.

Fig. 6.9 suggests a sequence of activities in the strategy management process.

The activities constitute the fundamental components of strategic management:

1. Environmental trends analysis and scenario building.

2. Industry and competitive analysis.

3. Identification of past and current strategy.

4. Strategy evaluation.

5. Identification of competitive advantages.

6. Strategic choice.

7. Cultural analysis.

8. Strategic change.