Learn about the different theories of Motivation studied in Management. Also Learn about:- 1. Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs Theory 2. Herzberg’s Two Factory Theory 3. McCelland’s Achievement Motivation Theory 4. McGregor’s Theory X and Theory Y 5. Vroom’s Expectancy Theory 6. The Porter and Lawler Model 7. Adam’s Equity Theory 8. Reinforcement Theory and Behaviour Modification.

Motivational Theory # 1. Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs Theory:

Maslow’s Hierarchy of needs theory proposes that people are motivated by multiple needs and that these needs exist in a hierarchical order.

The essential components of the theory may be stated thus:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

i. Adult motives are complex. No single motive determines behaviour, rather, a number of motives operate at the same time.

ii. Needs from a hierarchy. Lower level needs must at least partly be satisfied before higher level needs emerge. In other words, a higher order need cannot become an active motivating force until the preceding lower order need is essentially satisfied.

iii. A satisfied need is not a motivator. A need that is unsatisfied activates seeking behaviour. If a lower level need is satisfied, a higher level need emerges.

iv. Higher level needs can be satisfied in many more ways than the lower level needs.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

v. People seek growth. They want to move up the hierarchy of needs. No person is content at the physiological level. Usually, people seek the satisfaction of higher order needs.

Maslow identified five general types of motivating needs in order of ascendance, as given below:

(I) Physiological Needs:

Physiological needs are the biological needs required to preserve human life; these needs include needs for food, clothing and shelter. These needs must be met at least partly before higher level needs emerge. They exert a tremendous influence on behaviour.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

They are the most powerful of motivating stimuli; for we must satisfy most of them in order to exist (survive). These take precedence over other needs when thwarted. As pointed out by Maslow, “man lives by bread alone”, when there is no bread. Physiological needs dominate when all needs are unsatisfied.

Physiological needs have certain features in common:

i. They are relatively independent of each other.

ii. In many cases, they can be identified with a particular organ in the body (hunger-stomach etc.)

ADVERTISEMENTS:

iii. Physiological needs are essentially finite. An individual demands only a particular amount of these needs. After reasonable gratification, they are no longer demanded and hence not motivational.

iv. They must be met repeatedly within relatively short time periods to remain fulfilled.

v. Satisfaction of physiological needs is usually associated not with money itself but what it can buy. The value of money diminishes as one goes up the hierarchy.

(II) Safety Needs:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Once physiological needs become relatively well gratified, the safety needs begin to manifest themselves and dominate human behaviour. These include – (i) protection from physiological dangers (fire, accident); (ii) economic security (fringe benefits, health, insurance programmes); (iii) desire for an orderly, predictable environment; and (iv) the desire to know the limits of acceptable behaviour. Maslow stressed emotional as well as physical safety.

Thus, these needs are concerned with protection from hazards of life; from danger, deprivation and threat. Safety needs are primarily satisfied through economic behaviour. Organisations can influence these security needs either positively – through pension schemes, insurance plans — or negatively by arousing fears of being fired or laid off. Safety needs too, are motivational only if they are unsatisfied. They have finite limits.

(III) The Love Needs:

After the lower order needs have been satisfied, the social or love needs become important motivators of behaviour. Man is a gregarious being and he wants to belong, to associate, to gain acceptance from associates, to give and receive friendship and affection. Social needs tend to be stronger for some people than for others and stronger in certain situations.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Social needs have certain features in common:

i. They provide meaning to work life. Individuals are not treated as glorified machine tools in the production process. People congregate because of mutual feelings of being beaten by the system. They seek affiliation because they desire to have their beliefs confirmed.

ii. Social needs are regarded as secondary because they are not essential to preserve human life. They are nebulous because they represent needs of the mind and spirit, rather than of the physical body.

iii. Social needs are substantially infinite.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

iv. Social needs are primarily satisfied through symbolic behaviour of psychic and social content. Where these are not met, severe maladjustment is probable; where the hunger for companionship is assuaged, the mental health of the organism is once again on a better base.

(IV) The Esteem Needs:

Esteem needs are twofold in nature- self-esteem and esteem of others. Self-esteem needs include those for self-confidence, achievement, competence, self-respect, knowledge and for independence and freedom. The second group of esteem needs are those that related to one’s reputation- needs for status, for recognition, for appreciation and the deserved respect of one’s fellows / associates.

Esteem needs have certain features in common:

i. They do not become motivators until lower level needs are reasonably satisfied.

ii. These needs are insatiable; unlike lower other needs, these needs are rarely satisfied.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

iii. ‘Satisfaction of esteem needs produces feelings of self-confidence, worth, strength, capability and adequacy, of being useful and necessary in the world’ (Maslow). Thwarting them results in feelings of inferiority, weakness and helplessness.

iv. The modern organisation offers few opportunities for the satisfaction of these needs to people at lower levels in the hierarchy.

(V) The Self-Actualisation Needs:

These are the needs for realising one’s own potentialities for continued self-development, for being creative in the broadest sense of that term. “Self-fulfilling people are rare individuals who come close to living up to their full potential for being realistic, accomplishing things, enjoying life, and generally exemplifying classic human virtues.”

Self- actualisation is the desire to become what one is capable of becoming. A musician must make music, a poet must write, a general must win battles, an artist must paint, a teacher must teach if he is to be ultimately happy. What a man CAN be he MUST be. Self-actualisation is a ‘growth’ need.

Self-actualisation needs have certain features in common:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

i. The specific form that these needs take will vary greatly from person to person. In one person, it may be expressed materially, in still another, aesthetically.

ii. Self-realisation is not necessarily a creative urge. It does not mean that one must always create poems, novels, paintings and experiments. In a broad sense, it means creativeness in realising to the fullest one’s own capabilities; whatever they may be.

iii. The way self-actualisation is expressed can change over the life cycle. For example, John Borg, Rod Leaver, ‘Pele’ switching over to coaching after excelling in their respective fields.

iv. These needs are continuously motivational, for example- scaling mountains, winning titles in fields like tennis, cricket, hockey, etc. The need for self-realisation is quite distinctive and does not end in satisfaction in the usual sense.

v. These needs are psychological in nature and are substantially infinite.

vi. The conditions of modern life give only limited opportunity for these needs to obtain expression.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Maslow’s theory has been criticised on the following grounds:

a. Theoretical Difficulties:

The need hierarchy theory is almost a non-testable theory. It defies empirical testing, and it is difficult to interpret and operationalise its concepts. For example, what behaviour should or should not be included in each need category? What are the conditions under which the theory is operative? How does the shift from one need to another take place? What is the time span for the unfolding of the hierarchy?

After reviewing 22 studies, Wabha Bridwell concludes “review shows that Maslow’s theory has received little clear or consistent support. . . some of the propositions are totally rejected, while others receive mixed and unquestionable support at best”. Maslow’s simplified theory is grossly incomplete and must be viewed as a ‘theoretical statement rather than an abstraction from field research’.

b. Research Methodology:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Maslow’s model is based on a relatively small sample of subjects. It is a clinically derived theory and its unit of analysis is the individual. Maslow, recognising these limitations, presented the model “with apologies to those who insist on conventional reliability, validity, sampling, etc.”

c. Superfluous Classification Scheme:

The need classification scheme is somewhat artificial and arbitrary. Needs cannot be classified into neat watertight compartments, a neat 5 step hierarchy. The model is based more on wishes of what man SHOULD BE than what he ACTUALLY IS. Some critics have concluded that the hierarchy should be viewed merely a two-tiered affair, with needs related to existence (survival) at the lower level and all other needs grouped at the second level.

d. Chain of Causation in the Hierarchy:

There is no definite evidence to show that once a need has been gratified its strength diminishes. It is also doubtful whether gratification of one need automatically activates the next need in the hierarchy. The chain of causation may not always run from stimulus to individual needs to behaviour.

Further, various levels in the hierarchy imply that lower level needs must be gratified before a concern for higher level needs develop. In a real situation, however, human behaviour is probably a compromise of various needs acting on us simultaneously. The same need will not lead to the same response in all individuals. Also, some outcomes may satisfy more than one need.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

e. Needs — Crucial Determinants of Behaviour:

The concept of needs is introspective in nature, and so cannot be tested objectively. It is difficult to catalogue the multifarious needs of individuals and point out clearly as to how one need differs from another. Because of this limitation critics have questioned the usefulness of the needs theory. The assumption that needs are the crucial determinants of behaviour is also open to doubt. Behaviour is influenced by innumerable factors (not necessarily by needs alone).

Moreover, there is ample evidence to show that people seek objects and engage in behaviour that are in no way connected to the gratification of needs. No wonder, Vroom did not use the concept of needs while explaining ‘motivation’. It is also worth noting that the Maslow’s model presents a somewhat static picture of individual needs structure. The fact that the relative mix of needs changes during an individual’s psychological development has been ignored. In addition, a longitudinal view of needs is totally missing.

The needs of workers change over time inevitably. According to one authority, in the 1940s and 1950s, job security ranked as the most important thing that workers wanted from their jobs. In the 1960s and 1970s, interesting work ranked first. Owing to these limitations, the need priority model provides, at the best, an incomplete and partial explanation of behaviour.

f. Individual Differences:

Individuals differ in the relative intensity of their various needs. Some individuals are strongly influenced by love needs despite having a flourishing social life and satisfying family life; some individuals have great and continued need for security despite continued employment with enormous fringe benefits. Young workers have greater esteem and self-fulfillment deficiencies than the older workers.

Culturally disadvantaged employees may feel stronger deprivation of biological and safety needs, whereas culturally advantaged employees prefer satisfaction of higher order needs. Educated employees place a premium on challenging tasks. In comparison, less educated employees prefer routine and standardised jobs. The picture will be very confusing if we apply the theory in different countries with cultural, religious differences.

In one case, black managers had a greater lack of need fulfillment than their black counterparts in almost every category. Surveys in Japan and Continental European countries show that the model does not apply to the managers. Cultural, religious, environmental influences play a major role in determining the need priority in various countries.

Thus, the theory hardly reckons with a whole set of factors affecting individual need structure — race, position in authority structure, and culture, etc. Few (if any) data support the idea that all people are capable of activating all levels of the need structure. Moreover, managers do not have substantial amounts of time for a leisurely diagnosis of where every employee is positioned in the Maslow’s need priority model.

Maslow’s Contribution:

Maslow’s need hierarchy is no panacea for explaining motivational problems. The research studies clearly point out that Maslow’s is not the final answer in work motivation, despite its phenomenal popularity and appeal. However, it has provided a priori conceptual framework to explain various research findings.

Maslow’s need hierarchy provides researchers and practitioners neither with a system that gives complete understanding nor one that is invariant in its application, but it does provide a provocative template for the appreciation of the question of why people act as they do or what is motivation? Maslow’s theory accounts for interpersonal variations in behaviour.

Maslow’s model should be viewed at best as a general description of the average individual at a specific point in time; it must be viewed as a general theoretical statement, a hypothetical construct rather than an abstraction from field research. Even in its awkward form, the model seems to apply to underdeveloped countries. A survey of 200 factory workers in India points out that they give top priority to lower level needs’.

According to other studies, the model seems to apply to managers and professional employees in developed countries like UK; USA. The need priority model is useful because of its rich and comprehensive view of needs. The theory is still relevant because needs no matter how they are classified, are important for understanding behaviour.

It is simple to understand that it has a common sense appeal for managers. It has been widely accepted — often uncritically, because of its immense intuitive appeal only. It has survived, obviously more because of its aesthetics than because of its scientific validity.

Motivational Theory # 2. Herzberg’s Two Factory Theory:

Frederick Herzberg, a well-known management theorist, developed a specific “content theory of work motivation.” In the 1950s, he conducted a study of need satisfaction of 200 engineers and accountants employed by firms in and around Pittsburgh. He used the critical incident method for obtaining data for analysis. The purpose of his study was to find out what people want, and what motivates them.

He asked the subject to describe situations in which they found their jobs “exceptionally good” (and therefore motivating) or “exceptionally bad”. It was found that the employees named different kinds of conditions which caused each of the two feelings about their jobs. For example, if recognition led to a “good feeling”, the lack of recognition was seldom indicated as a cause of “bad feeling.”

The responses were tabulated and categorised. From the categorised responses, Herzberg concluded that the replies given when people feel good about their jobs are significantly different from the replies when they feel bad about it. Certain characteristics tend to be consistently related to job satisfaction and others to job dissatisfaction. ‘Intrinsic factors’ seem to be related to job satisfaction. When those questioned feel good about their work, they tended to attribute these characteristics to themselves. On the other hand, when they were dissatisfied, they tended to give ‘extrinsic factors’ as the main reasons.

Herzberg reached two basic conclusions:

i. Hygiene Factors:

There are some conditions of a job which operate primarily to dissatisfy employees when they are not present. However, the presence of these conditions does not bring strong motivation. Herzberg called these factors maintenance or hygiene factors, since they are necessary to maintain current status, i.e., a reasonable level of satisfaction. These factors cause much dissatisfaction when they are not present, but do not provide strong motivation.

He also noted that many of these have often been perceived by managers as factors which can motivate subordinates, but they are in fact, more patent as dissatisfiers when they are absent. In other words, adding more and more of these hygiene factors (like salary), to the job will not motivate them once the factor (salary) is adequate, these “hygienes” can only keep them from becoming dissatisfied.

In fact, such factors are peripheral to the job itself and more related to the external environment of work. When employees are highly motivated, they show a high tolerance for dissatisfaction arising from the peripheral factors. However, the reverse is not true.

ii. Motivators:

There are some job conditions which, if present, build high levels of motivation and job satisfaction. However, if these conditions are not present, they do not cause dissatisfaction. He called these ‘motivational factors’ or ‘satisfiers.’

There are:

a. Achievement.

b. Recognition.

c. Advancement (through creative and challenging work).

d. The work itself.

e. The possibilities of personal growth.

f. Responsibility.

Herzberg was of the opinion that these factors, lead to strong motivation, and, therefore, job satisfaction when they are present, but do not cause much dissatisfaction when they are absent.

The essence of Herzberg’s theory may be stated thus:

a. Motivators are directly related to job content itself, the individual’s performance of it, its responsibilities and the growth and recognition obtained from it, i.e., motivators are intrinsic to the job.

b. Maintenance and hygiene factors are extrinsic to the job. They do not provide motivation. If they are adequate and present, they only prevent dissatisfaction; they produce no improvement but are needed to avoid unpleasantness. In fact, they provide an almost neutral feeling among the workers of an organisation, but if withdrawn create dissatisfaction.

According to Herzberg, they help in maintaining “a zero level of motivation”, if they are given to workers, and dissatisfaction if they are withdrawn. Keith Davis says- “Motivators are job-oriented; they – relate to job content. Maintenance factors are mostly environment centered; they are related to job context.”

Gillerman observed- “The hygiene factors are prerequisites for effective motivation, but are powerless to motivate by themselves. They can build a floor under morale…. they do nothing to elevate the individual’s desire to do his job well.” These factors have to be maintained to avoid damage to efficiency or morale; but they are incapable of stimulating any positive effort.

c. In Herzberg’s jargon, “Money and fringe benefits are known as negative motivators”, for their absence from a job unquestionably will make people unhappy, but their presence does not necessarily make them happier or more productive.

d. Fredrick Herzberg says that man has two different sets of needs – one, “lower level” set drives from man’s desire to avoid pain and satisfy his basic needs, as well as need for money to pay for basic needs. In this respect, it is similar to Maslow’s ‘physiological’ and ‘safety needs.’ We often find that money is still a motivator for non-management worker (particularly those at a minimum wage level) and for some managerial employees too.

Man has also “higher level” set of needs, which “relate to that unique characteristic- the ability to achieve, and to experience psychological growth.” Included here are the needs to achieve a difficult task, to obtain prestige, and to receive recognition. It is similar to Maslow’s ‘social’, ‘ego’ and ‘self- actualisation’ needs.

e. Herzberg says that the data suggest that the opposite of ‘satisfaction’ is not ‘dissatisfaction’, as was traditionally believed. Removing dissatisfying characteristics from a job does not necessarily make the job satisfying, or vice versa. Herzberg proposed that his findings indicate the existence of dual continuum- the opposite of ‘satisfaction’, is ‘no satisfaction’, the opposite of “dissatisfaction” is “no dissatisfaction.”

f. Finally, the factors leading to job satisfaction are separate and distinct from those that lead to job dissatisfaction. Therefore, if a manager seeks to eliminate factors that can create job dissatisfaction, he can bring about peace, but not necessarily motivation. He will be placating his subordinates rather than motivating them. Hence, if employees are to be motivated “satisfiers” should be stressed upon.

Other studies have confirmed the conclusions of Herzberg.

The motivational studies conducted at Texas Instruments have shown that the things that motivate employees are:

i. A challenging job which offers a feeling of achievement, responsibility, growth, advancement, enjoyment of the work itself, and recognition;

ii. Factors which are peripheral to job-work rules — lighting, coffee-breaks, titles, seniority rights, wages, fringe benefits, and the like; and

iii. Opportunities for meaningful achievement; if these are eliminated, workers become sensitised to their environment and begin to find fault with it.

Scott Meyers concludes that Herzberg’s hygiene theory “is easily translatable to supervisory action at all levels of responsibility. It is a framework on which supervisors can evaluate and put into perspective and constant barrage of ‘helpful hints’ to which they are subjected, and serves to increase their feelings of competence, self-confidence and autonomy.”

Observe Hersey and Blanchard – “In a motivating situation, if you know what are the high strength needs (Maslow) of the individuals you want to influence, then you should be able to determine what goals (Herzberg) you can provide in the environment to motivate those individuals. At the same time, if you know what goals these people want to satisfy, you can predict what their strength needs are.

That is possible because it has been found that money and benefits tend to satisfy needs at the physiological and security levels; interpersonal relations and supervision are examples of the hygiene factors which tends to satisfy social needs; increased responsibility, challenging work, growth and development are motivators that tend to satisfy needs at the esteem and self-actualisation levels.

Critical Evaluation of Two Factory Theory:

Herzberg’s theory has, however, been criticised by many authors.

i. Doubts Regarding its Applicability:

Keith Davis has observed that a limited testing of the model on blue-collar workers suggests that some items normally considered as maintenance factors (such as pay and security) are frequently considered motivational factors by blue-collar workers. A study has reported that both motivation and maintenance factors are positively related to the job satisfaction of blue-collar workers. Another study has indicated that blue- collar workers lay greater stress on extrinsic job factors.

ii. The Two Sets of Factors are not Mutually Exclusive:

Some authorities have doubted whether in factors leading to satisfaction and dissatisfaction are really different from each other. It has been contended that achievement, recognition and responsibility are important for both satisfaction and dissatisfaction, while such dimensions as security, salary and working conditions are less important. Michael and Barry say that “the subjects consisted of engineers and accountants.

The fact that these individuals were in such positions indicates that they had the motivation to seek advanced education and expect to be rewarded for it. The same may not hold true for the non-professional worker…. Some of the factors considered as ‘maintenance factors’ by Herzberg (pay, job security) are considered by blue-collar workers to be “motivational factors”.

iii. Drawing the Certain between Hygiene and Motivators is Not Easy:

According to Vroom, “Herzberg’s inference regarding differences between ‘dissatisfiers’ and ‘motivators’ cannot be completely accepted, and that the differences between stated sources of ‘satisfaction’ and ‘dissatisfaction’ may be the result of defensive processes within those responding….People are apt to attribute the causes of satisfaction of their own achievements, but more likely to attribute their dissatisfaction to obstacles presented by company policies or superiors than to their deficiencies.”

iv. Oversimplification of a Complex Reality:

Another group of writers believe that the two factor theory is an oversimplification of the true relationship between motivation and dissatisfaction. They reviewed several studies which showed that one factor can cause job satisfaction for one person and job dissatisfaction for another. They concluded that further research is needed to enable to predict in which situation worker satisfaction will produce greater productivity.

v. Questionable Research Methodology:

House and Wigdor have based their criticism on the basis of the five weaknesses, namely:

a. The procedure the Herzberg used is limited by its methodology. When things are going well, people tend to take credit for themselves. Contrarily, they blame failure to the extrinsic environment.

b. The reliability of the methodology is questioned, since raters have to make interpretations, it is possible that they may contaminate the findings by interpreting one response in one manner while treating another response differently.

c. No overall measure of satisfaction was utilised. In other words, a person may not like a part of his job, yet still think the job is acceptable.

d. The theory is inconsistent with previous research. The motivation-maintenance theory ignores situational variables.

e. Herzberg assumes that there is a relationship between satisfaction and productivity. But the research methodology he used looked only at satisfaction, not at productivity. To make such research relevant, one must assume a high relationship between satisfaction and productivity.

Since his original study, Herzberg has cited numerous and diverse replications of the original study which support his position. These subsequent studies were conducted on professional women, hospital maintenance personnel, agricultural administrators, nurses, food handlers, manufacturing supervisors, engineers, scientists, military officers, managers ready for retirement, teachers, technicians, and assemblers and some were conducted in other cultural setting — Finland, Hungary, Russia and Yugoslavia.

However, other researchers who have used the same research methods employed by Herzberg have obtained results different from what his theory would predict; while several others using different methods have also obtained contradictory results.

The above discussion indicates that Herzberg’s theory has met severe criticism. However, it cannot be denied that- (i) it has cast a new light on the content of work motivation. Up to this time, management had generally concentrated on the hygienic factors; (ii) it contributed substantially to Maslow’s ideas and made them more applicable to the work situation; (iii) it drew attention to the importance of job content factor in work motivation, which previously had been neglected and often totally overlooked; and (iv) it contributed, to job design technique or job enrichment.

Overall, it added much to the better understanding of job-content factors and satisfaction, but it fell short of a comprehensive theory of work motivation. His model describes only some of the content of work motivation — it does not adequately describe the complex human motivational process in modern organisations.

Motivational Theory # 3. McCelland’s Achievement Motivation Theory:

David C. McCelland, a Harvard psychologist, has proposed that there are three major relevant motives or needs in workplace situations. His theory is closely associated with the achievement motive.

According to him, the motives are:

i. The need for achievement (which he calls n Ach) – the drive to excel, to achieve in relation to a set of standards, to strive to succeed.

ii. The need for application (or n Apl) – the drive for friendly and closely interrelated relationships.

iii. The need for power (n Pwr) — need to make others behave in a way that they would not behaved otherwise.

According to him, every motive is a learned one and only two are innate, namely, striving for pleasure and seeking to avoid displeasure or pain. All other motives are acquired. These two factors are at the opposite ends of a continuum — one end is an approach to the expectation of pleasure and satisfaction and the other is negative avoidance of pain or displeasure. From his researches, McCelland found that, achievement motive is a “desire to perform in terms of a standard of excellence or to be successful in competitive situations.”

High achievers, it should be noted, flourish in competitive situations. They prefer challenging assignments. They are willing to work hard and want jobs that stretch their abilities fully. They are not motivated by money perse but instead, employ money as a method of keeping score of their achievements.

The need for application (n Apl) is closely related to having a strong desire to maintain close friendship and to receive affection from others. Such people constantly seek to establish friendly relationships.

The need for power (n Pwr) is closely related to managerial success. People with high needs for power prefer situations in which they can get and maintain control of the means for influencing others. They like being in the position of making suggestions, giving their opinions, and talking others into things. This satisfies their need for “power.” In sum, it should be noted that according to McCelland, everyone has each of these needs to some degree.

However, no two people have them in exactly the same proportions. For example, one person may be very high in his ‘need for achievement’ but low in his ‘need for affiliation.’ Another person might be high in his need for affiliation but low in his need for power. Secondly, the achievement motive does not encourage excessive risk taking, speculation, gambling, etc. People with a high degree of achievement drive are neither conservative nor fond of a gamble.

They generally take a middle path. The reason is that such a man would like to influence, the result to be achieved by his efforts and skills rather than relay on chance. Thirdly, the theory was put to test both in developed and underdeveloped economies, in free enterprise economies and even in a communist society, the conclusion has been that under all conditions successful executives seem to have a strong achievement motivation.

McClelland’s theory has significant implications for managers. If the needs of employees can be measured accurately, organisations can improve the selection and placement processes. People with a high need for achievement may be placed on challenging, difficult jobs. People with a high need for power may be trained for leadership positions. If the organisation is able to achieve a ‘fit’ between need intensities and job characteristics, improved performance is guaranteed.

According to McClelland, in addition to pumping achievement characteristics into jobs, people should be taught, and offered training in achievement motivation.

Motivational Theory # 4. McGregor’s Theory X and Theory Y:

Douglas McGregor proposed two distinct sets of assumptions about what motivates people — one basically negative, labeled Theory X and the other basically positive, labeled Theory Y.

Theory X:

Theory X contends that people have an inherent dislike of work and will avoid it whenever possible. Most people, being lazy, prefer to be directed, want to avoid responsibility and are relatively unambitious. They must be coerced, controlled, directed or even threatened with punishment to get them to work towards organisational goals.

External control is clearly appropriate for dealing with such unreliable, irresponsible and immature people. Managers have to be strict and authoritarian if subordinates are to accomplish anything.

Theory X thus, assumes that lower-order needs (Maslow) dominate human behaviour. Money, fringe benefits and threats of punishment play a great role in putting people on the right track under this classification scheme.

Theory Y:

Theory Y presents a much more optimistic view of human nature. It assumes that people are not, by nature, lazy and unreliable. They will direct themselves towards objectives if their achievements are rewarded. Most people have the capacity to accept, even to seek, responsibility as well as to apply imagination, ingenuity, and creativity to organisational problems.

If the organisational climate is conducive, people are eager to work; and they derive a great deal of satisfaction from work, and they are capable of doing a good job. Unfortunately, the present industrial life does not allow the employees to exploit their potential fully. Managers, therefore, have to create opportunities, remove obstacles and encourage people to contribute their best.

Theory Y, thus, assumes that higher-order needs (Maslow) dominate human behaviour. In order to motivate people fully, McCregor proposed such ideas as participation in decision-making, responsible and challenging jobs and good group relations in the workplace.

The essence of Theory Y is that “workers will do far more than is expected of them if treated like human beings and permitted to experience personal satisfaction on the job.” Theory Y places the programmes squarely in the lap of management. If employees are lazy, indifferent, unwilling to take responsibility, intransigent, uncreative, un-cooperative, the causes lie in management’s methods of organisation and control.

The managers who believe in this theory put emphasis on, consultation, participation, motivation, communication, opportunities in formulating managerial and personnel policies.

McGregor has also suggested a number of innovative ideas which are consistent with Theory Y and are being practised in American industry, viz.:

i. Greater decentralisation and delegation of authority, i.e., freeing subordinates from too close control and satisfying their need for freedom, for a sense of responsibility.

ii. Job enlargement, i.e., increasing responsibility among rank and file workers by providing opportunities for satisfying social and ego needs.

iii. Participation and consultative management, where employees are given opportunity to take part in decision-making.

iv. Target setting for performance, in consultation with the employees concerned and a self- evaluation of performance periodically.

Further clarifications have been offered by McGregor in his work published posthumously.

He has stated:

i. Theory X and Theory Y are not the only two possible theories of management. These were examples of two among many managerial cosmologies.

ii. The two theories are not managerial strategies. They are underlying beliefs about the nature of man that influence managers to adopt one strategy rather than another.

iii. The belief that man is essentially like a machine that is set in motion by the application of external forces differs in more than degree from the belief that man is an organic system where behaviour is affected not only by external forces but by intrinsic one. Theory X and Theory Y are not, therefore, polar opposites; they do not lie at extremes of a scale. They are simply different cosmologies.

William Ouchi, after making a comparative study of American and Japanese management practices, proposed Theory Z in early 80s. It is an integrative model, containing the best of both worlds. It takes into account the strengths of Japanese Management (social cohesion, job security, concern for employees) as well as American management (speedy decision-making, risk taking skills, individual autonomy, innovation and creativity) and proposes a ‘mixed US’ Japanese management system for modern organisations.

The mixed / hybrid system has the following characteristics:

a. Trust:

Trust and openness are the building blocks of Theory Z. The organisation must work toward trust, integrity and openness. In such an atmosphere, the chances of conflict are reduced to the minimum. Trust, according to Ouchi, means trust between employees, supervisors, work groups, management, unions and government.

b. Organisation-Employee Relationship:

Theory Z makes a passionate plea for strong linkages between employees and the organisation. It argues for lifetime employment for people in the organisation. To ensure stability of employment, managers must make certain conscious decisions. When there is a situation of lay-off, for example, it should not be followed and instead, the owners / shareholders may be asked to bear with the losses for a short while.

To prevent employees from reaching a ‘plateau promotions may be slowed down. Instead of vertical progression, horizontal progressions may be laid down clearly so that employees are aware of what they can achieve and to what extent they can grow within the organisation, over a period of time.

c. Employee Participation:

Participation here does not mean that employees must participate in all organisational decisions. There can be situations where management may arrive at decisions without consulting employees (but informed later on); decisions where employees are invited to suggest but the final green signal is given by management.

But all decisions where employees are affected must be subjected to a participative exercise; where employees and management sit together, exchange views, take down notes and arrive at decisions jointly. The basic objective of employee involvement must be to give recognition to their suggestions, problems and ideas in a genuine manner.

d. Structureless Organisation:

Ouchi proposed a structureless organisation run not on the basis of formal relationships, specialisation of positions and tasks but on the basis of teamwork and understanding. He has given the example of a basketball team which plays together, solves all problems and gets results without a formal structure. Likewise in organisations also the emphasis must be on teamwork and cooperation, on sharing of information, resources and plans at various levels without any friction.

To promote a ‘systems thinking’ among employees, they must be asked to take turns in various departments at various levels. Job rotation enables them to learn how work is processed at various levels; how their work affects others or is affected by others, it also makes the employees realise the meaning of words such as ‘reconciliation’, ‘adjustment’ and ‘give and take’ in the organisational context.

e. Holistic Concern for Employees:

To obtain commitment from employees, leaders must be prepared to invest their time and energies in developing employee skills, in sharing their ideas openly and frankly, in breaking the class barriers, in creating opportunities for employees to realise their potential. The basic objective must be to work co-operatively, willingly and enthusiastically.

The attempt must be to create a healthy work climate where employees do not see any conflict between their personal goals and organisational goals.

Indian companies have started experimenting with these ideas in recent times, notably in companies like Maruti Udyog Limited, BHEL, by designing the workplace on the Japanese pattern by having a common canteen, a common uniform both for officers and workers, etc.

Other ideas of Ouchi such as lifelong employment, imbibing a common work culture, participative decisions, structureless organisations, owners bearing the temporary losses in order to provide a cushion for employees may be difficult to find any meaningful expression on the Indian soil because of several complicating problems.

The differences in culture (north Indian and south Indian), language (with over a dozen officially recognised ones), caste (forward, backward, scheduled caste, scheduled tribe, economically backward), religion (Hindu, Muslim, Sikh, Jain, Christian, etc.), often come in the way of transforming the seemingly appealing Western rhetoric into concrete action plans.

Motivational Theory # 5. Vroom’s Expectancy Theory:

This theory was developed by Victor H. Vroom and it expands upon those developed by Maslow and Herzberg. It views motivation as a process governing choices. Thus, if an individual has a particular goal, in order to achieve the goal, some behaviour must be performed.

The individual, therefore, weighs the likelihood that various behaviours will achieve the desired goal, and if certain behaviour is expected to be more successful than others that type of behaviour will likely be selected.

An important contribution of Vroom’s theory is that it explains how the goals of individuals influence their effort and that the behaviour individuals select depends upon their assessment of the probability that the behaviour will successfully lead to the goal.

For example, all members of an organisation may not place the same value on such job factors as promotion, high pay, job security, and working conditions. In other words, they may rank them differently. Vroom believes that what is important is the perception and value the individual places upon certain goals.

The expectancy theory argues that the strength of a tendency to act in a certain way depends in the strength of an expectation that the act will be followed by a given outcome and on the attractiveness of the outcome of the individual.

It includes three variables:

i. Attractiveness – The importance or the strength that the individual places on potential outcome or reward that can be achieved on the job. This considers the unsatisfied needs of the individual.

ii. Performance – Reward Linkage- The degree to which the individual believes that performing of particular level will lead to the attainment of each job outcome.

iii. Effort – Performance Linkage- The perceived probability by the individual that exerting a given amount of effort will lead to performance.

In other words, a person’s desire to produce at any given time depends on his particular goals and his perception of the relative worth of performance as a path to the attainment of these goals. The strength of a person’s motivation to perform (effort) depends upon how strongly he believes that he can achieve what he attempts.

The four steps inherent in Vroom’s theory are:

1. What outcome does the job offer the employee?

The important issue to be considered is what individual employee perceives the outcome to be. Outcomes may be positive — such as pay security, companionship, trust, fringe benefits, a chance to use talents or skills, congenial relationship — or negative, such as fatigue, boredom, frustration, anxiety, harsh supervision, threat of dismissal, etc.

2. How attractive do employees view these outcomes?

This issue is related to the individual and considers his likes and dislikes. If a particular outcome is found to be attractive (positive), an individual would prefer attaining it to not attaining it. If it is negative, he would prefer not attaining it to attaining it. Additionally, he may be neutral.

3. What kind of behaviour must the employee produce in order to achieve these objectives?

The outcomes can be effective only when the employee knows clearly what he must do in order to achieve them — i.e., he should know what are the criteria on the basis of which his performance would be judged.

4. How does the employee view his chances of doing what is asked of him?

After knowing his competencies and his abilities, the individual should ascertain the probability of his successful attainment of the job.

In sum, Vroom emphasises the importance of individual perceptions and assessments of organisational behaviour. The key to “expectancy” theory is the “understanding of an individual’s goals” — and the linkage between “effort” and “performance”, between “performance” and “rewards,” and between “rewards” and “individual-goal satisfaction”. It is a contingency model, which recognises that there is no universal method of motivating people.

Because we understand what needs an employee seeks to satisfy does not ensure that the employee himself perceives high job performance as necessarily leading to the satisfaction of these needs.

Vroom’s model has brought forward the following particulars:

i. Its emphasis is on pay-off or rewards. In other words, the reward an organisation offers aligns with what the employee wants.

ii. We have to be concerned with the attractiveness of rewards, which requires understanding and knowledge of what value the individual puts on organisation pay-off. Individual should be rewarded with those he values positively.

iii. It emphasises expected behaviours, i.e., the individual should know what is expected of him and how he will be appraised.

iv. It implies that management should counsel subordinates to help them grasp a realistic view of their competency.

v. The Management should support the subordinates in developing those skills that are important in leading to better performance.

vi. It also implies that management should make an extended effort of demonstrating confidence in individuals that they can perform well.

vii. It has been used to explain specific forms of employee behaviour; for example, the turnover of younger workers, during pre-job training.

Implications for Managers:

From management’s point of view, the implications of this theory are twofold- First, it is important to determine what needs each employee seeks to satisfy. This knowledge will be useful to management while attempting to align rewards available to the employee with the needs that the employee seeks to satisfy. It is necessary to individualise rewards to each employee, for rewards that are valuable for some may not be appealing to others.

Second, management should attempt to clarify the path for the worker between efforts and need satisfaction. Individual motivation will be significantly determined by the probabilities the worker assigns to the following relationships- His effort leading to performance?? Performance leading to rewards, and these rewards?? Satisfying personal goals. Vroom’s theory, in sum, indicates only the conceptual determinants of motivation and how they are related.

It does not provide specific suggestions on what motivates humans in organisation, as did the Maslow and Herzberg models. It is, however, of value in understanding organisational behaviour. It clarifies the goals between individual and organisational goals. It attempts only to mirror the complex motivational process; it does not attempt to describe how motivational decisions are actually made or to solve actual motivational problems facing a manager. It needs further testing to prove its validity.

Motivational Theory # 6. The Porter and Lawler Model:

This model starts with the premises that – (a) motivation (effort or force) does not equal satisfaction and / or performance. Motivation satisfaction and performance are all separate variables and related in different ways; (b) effort (force or motivation) does not directly lead to performance. It is mediated by abilities / traits and role perceptions; and (c) the rewards that follow and how these are perceived will determine satisfaction.

In other words, Porter and Lawler model suggests that performance leads to satisfaction. Efforts, performance, rewards, and satisfaction are major variables in the model.

The model was only a conceptual scheme to guide and structure a study. Serious thinkers have stated that the “relationship between performance and satisfaction is extremely complex and the role of rewards should be given more attention.” Green concluded that “…(1) rewards constitute a more direct cause of satisfaction than does performance, and (2) rewards based on current performance (and not satisfaction) cause subsequent performance.”

Although the model is more application-oriented, it is still quite complex and has proved to be a difficult way to bridge the gap to actual management practice. It states that- (a) management should go beyond traditional attitude measurement and attempt to measure variables such as the values of possible rewards, the perception of the effort-reward possibilities and role perceptions. These variables can help managers better understand what goes into employee effort and performance, (b) The managers should critically re-evaluate concentrated effort to measure how closely levels of satisfaction are related to levels of performance.

Motivational Theory # 7. Adam’s Equity Theory:

Adam’s Theory of Equity is one of the popular social exchange theories and is perhaps the most rigorously development statement of how individuals evaluate social exchange relationships. It is probably the clearest of the process theories. Basically, the theory points out that people are motivated to maintain fair relationships with others and will try to rectify unfair relationships by making them fair.

This theory is based on two assumptions about human behaviour:

i. Individuals make contributions (inputs) for which they expect certain outcomes (rewards). Inputs include such things as the person’s past training and experience, special knowledge, personal characteristics, etc. Outcomes include pay, recognition, promotion, prestige, fringe benefits, etc.

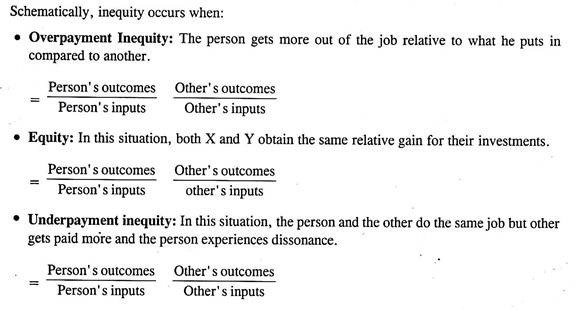

ii. Individuals decide whether or not a particular exchange is satisfactory, by comparing their inputs and outcomes to those of others in the form of a ratio. Equity exists when an individual concludes that his/her own outcome/input ratio is equal to that of other people.

Adam states that “cognitive dissonance exists for person whenever his cognition of his job inputs and / or outcomes stands psychologically in obverse relation to his cognitions of the inputs and / or outcomes of others.”

How to Escape Inequity?

Suppose X and Y are two typists who perform the same type of work in two different divisions of a company. Assume that X is paid X 10,000 a month and Y is paid only Rs.8000 a month. One day, they meet and find out this unfortunate payment plan. According to equity theory, both X and Y will feel upset by this inequity. X will feel guilty for being paid more and Y will resent the underpayment and will be frustrated.

Now the question arises- how to bring about equity in their relationship? For instance, X can do more or better work than Y and can do less or poorer work to equalise their ratios. This is termed as ‘behavioural inequity resolution strategy’. Another method to lower one’s inputs is to remain absent from work. X and Y can also attempt to adjust their outcomes to resolve inequity, for example X may refuse pay raises and Y can demand for a raise. Y may type for others against attractive remuneration in an attempt to raise his outcomes.

If X lowers his outcomes and Y raises his, they equalise their ratios and they may help to establish a fair relationship. Alternatively, they may decide to quit and get out of the relationship completely. Quitting a job, obtaining a transfer, absenteeism are common forms of leaving the field. It is also possible to establish equity psychologically (psychological inequity resolution strategy). X and Y can convince themselves that X actually works harder than Y.

Quite often; inequitably paid workers convince themselves that they really are not working hard, thereby establishing equity between themselves and equitably paid workers. Thus, to restore equity, the person may alter the inputs or outcomes, cognitively distort the inputs or outcomes, leave the field, act on the other, or change the other.

The Major Postulates of the Theory:

1. Perceived inequity creates tension in the individual.

2. The amount of tension is proportional to the magnitude of the inequity.

3. The tension created in the individual will motivate him/her to reduce it.

4. The strength of the motivation to reduce inequity is proportional to the perceived inequity.

In other words, the presence of inequity motivates the individual to change the situation through various means to return to a condition of equity. Equity theory generally argues that it is the perceived equity of the situation that stimulates behaviour and satisfaction. Employee perception of the situation is more important here than objective ‘reality’.

Research Evidence:

A large number of empirical studies have tested the components of equity theory under different conditions. The evidence supports most of the predictions of the theory. People paid on hourly basis who believes they are underpaid generally reduce both the quantity and quality of that which they are producing.

Studies by Arrowood (1961), Andrews (1967), Goodman and Friedman (1968) supported the equity theory prediction when two groups of subjects are paid on exactly the same basis those who view themselves as ‘overpaid’ performed substantially better. A recent study by Pritchard, Dunnette and Jorgenson, clearly revealed support for the theory-underpaid workers were less productive than equitably paid workers and overpaid workers were more productive than equitably paid workers.

1. It is somewhat narrow in its emphasis on visible rewards and over emphasises conscious processes.

2. It is difficult to assess the perceptions (misperceptions) of employees. Hence, the difficulty in operationalising the concepts of the theory. In the words of Dunham, although easily understood the theory is complex and difficult in to apply.

3. How does a person choose the Comparison Other? The process by which individuals decide whom to compare themselves with is not clearly understood at present. According to Hammer and Organ, ‘one of the weakest elements of equity theory is its analysis of the process by which individuals choose a Comparison Other’.

4. Equity theory is not precise enough to predict which actions are most probable.

In spite of these limitations, equity theory is a promising motivation theory and has direct relevance for compensation practice.

According to Edwin Locke, motivation is a result of rational and intentional behaviour. The direction of the behaviour is a function of the goals individuals set and their efforts toward achieving these goals. The theory suggests that managers and subordinates should establish goals for the individual on a regular basis.

These goals should be moderately difficult (in fact, people will extend more effort to reach the more difficult goals if they have been rewarded for mastering difficult tasks in the past) and very specific (specificity is enhanced by setting goals into quantifiable terms).

Moreover, they should be of a type that the employee will accept and commit to accomplishing. Goal acceptance is simply the degree to which individuals accept goals as their own. Goal commitment is the dedication which individuals extend toward reaching the set objective rewards should be linked directly to reaching the goals.

Thus, the theory maintains that relevant and challenging goals which take care of individuals’ capabilities should be developed. The task before managers becomes one of guiding employees in the development and attainment of goals which will provide satisfaction to both the employee and the organisation.

This process is facilitated by the involvement of workers in organisational goal setting, the setting of challenging and specific individual goals, the provision of continual performance feedback and the establishment and implementation of appropriate rewards for describable performance.

Motivational Theory # 8. Reinforcement Theory and Behaviour Modification:

Reinforcement theory states that behaviour that results in rewarding consequences is likely to be repeated, whereas behaviour that results in punishing consequences is less likely to be repeated.

Four types of reinforcement strategies are generally used by managers to influence the behaviour of employees:

1. Positive Reinforcement:

It is the administration of a pleasant and rewarding consequence following a desired behaviour. A good example of this is immediate praise for an employee who arrives on time and completes the assigned work. ‘A pat on the back’ on such occasions will spur the employee to repeat such behaviours time and again.

People generally will expend considerable energy to gain positive rewards (pay, bonuses, recognition, time off with pay, commendations, promise of raise, etc.) which they desired. Of course, for positive reinforcement to have the desired impact, feedback must be consistent and frequent.

2. Negative Reinforcement:

Sometimes termed avoidance learning, negative reinforcement occurs when an unpleasant or undesirable situation is removed or withdrawn following some behaviour. A supervisor, for example, may continually reprimand and harass an employee until the employee begins performing a job correctly, at which point the harassment stops. If the employee continues to perform the job correctly in the future, then the removal of the unpleasant situation (the harassment) is said to have negatively reinforced effective job performance.

3. Extinction:

Extinction is an effective method of controlling undesirable behaviour. It refers to non-reinforcement. It is based on the principle that if a response is not reinforced, it will eventually disappear. If a teacher ignores a noisy student, the student may drop the attention- getting behaviour. Extinction is less painful than punishment because it does not involve the direct application of an aversive consequence. Students who perform well are praised quite often by the teachers.

If they begin to slack off and turn out poor performance, the teacher may try to modify their behaviour by withholding praise. Here, the teacher is not trying to punish the students by imposing fines or rebuking openly in the class or expelling them. The student is simply denied any feedback.

Extinction is a behavioural strategy that does not promote desirable behaviours but can reduce undesirable behaviours. If the students eventually show good work, the teacher may again praise them (positive reinforcement) but if poor performance is again resulting in, extinction will be re-employed.

4. Punishment:

Punishment is a control device employed in organisations to discourage and reduce annoying behaviours of others. It can take either of two forms- there can be withdrawal or termination of a desirable or rewarding consequence or there can be an unpleasant consequence after a behaviour is performed. Punishment reduces the response frequency; it weakens behaviour. The use of aversive control is the most controversial method of modifying behaviour because it produces undesirable by-products.

i. Punishment reduces the frequency of undesired behaviour, but it does not promote desired behaviour. I call Joe in, give him heck for goofing-up, and he goes right back out and goofs-up again. Punishment in such cases reinforces behaviour rather than reducing it.

ii. The frequency of undesirable behaviour is reduced only when the punishing agent is present. Punishment causes anxiety and suppresses the response which reappears when the punishing agent is absent. When the cat is away, the mice will play.

iii. Punishment frustrates the punishment and leads to antagonism toward the punishing agent. As a result, the effectiveness of the punishing agent diminishes over time.

Reinforcement schedules indicate the timing of reinforcement. The effectiveness of the reinforcer depends as much upon it’s scheduling as upon any of its other features like magnitude, quality and degree of association with the behavioural act. Essentially, there are two types of reinforcement schedules- continuous and intermittent. Under continuous reinforcement, the individual receives a reward every time he or she performs a desired behaviour.

With this schedule, behaviour increases very rapidly but when the reinforcer is removed performance declines rapidly. Another difficulty here is that it is not possible for a manager to reward the employee continuously for emitting desired behaviour. It is administratively impractical because employees cannot be rewarded each time they produce something.

Under intermittent reinforcement, the rewards (pay, praise, recognition, promotion, etc.) are administered on a random basis because it is not possible to reinforce desirable behaviours each time they occur. Intermittent reinforcement leads to slower learning but stronger retention of a response than continuous reinforcement.

Forster and Skinner have pointed out four ways of arranging intermittent schedules:

1. Fixed Interval Schedule:

This schedule demands that a fixed amount of time has to elapse before reinforcement is administered. In many organisations, monetary reinforcement comes at the end of a period of time. Most workers are paid hourly, weekly or monthly for the time spent on their jobs. This method offers the least motivation for hard work among workers because pay is tied to time interval rather than actual performance.

2. Variable Interval Schedule:

Under this schedule, reinforcers are dispensed unpredictably. The reward is given after a randomly distributed length of time. This is an ideal method for administering praise, promotions and supervisory visits. Variable interval schedules produce higher rates or response and more stable and consistent performance.

Suppose the plant manager visits the production department at 11 am approximately each day (fixed interval), performance tends to be high just prior to his visit and thereafter it declines.

Under variable interval schedule, the manager visits at randomly selected time intervals and no one knows for sure when the manager will be around. As a result, performance tends to be higher and have less fluctuation than under the fixed interval schedule.

3. Fixed Ratio Schedule:

In this schedule, reinforcement is given after a certain number of responses. This is basically the piece-rate schedule for pay. This schedule tends to produce high rate of response which is both vigorous and steady. Workers try to produce as many pieces as possible in order to pocket the monetary rewards. Therefore, the response level here is significantly higher than that obtained under an interval schedule.

4. Variable Ratio Schedule:

In the schedule, reinforcement is given in an irregular manager. The reward is given after a number of responses but the exact number is randomly varied. Individuals playing slot machines (gambling) are operating under a variable ratio schedule. These machines pay off after swallowing a number of coins. Since gamblers never know when they will be lucky, they often respond at a very high rate.

Another example of this type of schedule might be provided by the actions of workers in an oyster-processing plant. “Every so often (no one can predict when) an oyster being opened is found to contain a pearl.” Here, the workers never know when fate will smile upon them in this way; they work at a high rate, striking as many oysters as they can each day.

Organisation Behaviour Modification (OB Mod) is the name given to the set of techniques by which reinforcement theory is used to modify human behaviour. The basic assumption underlying OB Mod is the law of effect which states that behaviour that is positively reinforced tends to be repeated, and behaviour that is not reinforced tends not to be repeated.

To effectively implement OB Mod programmes, the following steps are suggested (K. E. Chung):

1. Define the Target Behaviour:

The target behaviour refers to a specific behaviour that management wants to modify. It can be attendance, cooperation, or actual production.

2. Develop Performance Goals:

The target behaviour needs to be translated into specific performance goals, such as improving attendance, increasing sales or expending market shares.

3. Assess Performance Progress:

Performance should be assessed periodically to provide employees with feedback on their progress. If they know they are doing well, this knowledge reinforces their behaviour; if they are not, they can take corrective action.

4. Match Performance with Rewards:

Unless rewards are tied to performance, they quickly lose motivational effect. Rewards can be tied to performance on an individual or a group basis. An individual-based reward system is used to encourage competition; a group-based system is to encourage co-operation.

A number of theories and explanations have been discussed. If you are a manager concerned with motivating your employees, how do you apply these theories?

The following suggestions offered by experts may help you in solving the puzzle to some extent:

1. Recognise Individual Differences:

Employees are not homogeneous. They have different needs. They also differ in term of attitudes, personalities and other important variables. So, recognise these differences and handle the motivational issues carefully.

2. Match People to Jobs:

People with high growth needs perform better on challenging jobs. Achievers will do best when the job provides opportunities to participative set goals and when there is autonomy and feedback. At the same time, keep in mind that, not everybody is motivated in jobs with increased autonomy, variety and responsibility. When the right job is given to the right person, the organisation benefits in innumerable ways.

3. Use Goals:

Provide specific goals, so that the employee knows what he is doing. Also, let people know what you expect of them. Make people understand that they can achieve the goals in a smooth way. If you expect resistance to goals, invite people to participate in the goal- setting process.

4. Individualise Rewards:

Use rewards selectively, keeping the individual requirements in mind. Some employees have different needs, what acts as a motivator for one may not for another. So, rewards such as pay, promotion, autonomy, challenging jobs, participative management must be used keeping the mental make-up of the employee in question.

5. Link Rewards to Performance:

Make rewards contingent on performance. To reward factors other than performance (favouritism, nepotism, regionalism, apple-polishing, yes-sir culture etc.), will only act to reinforce (strengthen) those other factors. Employee should be rewarded immediately after attaining the goals. At the same time, managers should look for ways to increase the visibility of rewards.

Publicise the award of performance bonus, lump-sum payments for showing excellence, discussing reward structure with people openly — these will go long way in increasing the awareness of people regarding the reward-performance linkage.

6. Check the System for Equity:

The inputs for each job in the form of experience, abilities, effort, special skills, must be weighed carefully before arriving at the compensation package for employees. Employees must see equity between rewards obtained from the organisation and the efforts put in by them.

7. Don’t Ignore Money:

Money is a major reason why most people work. Money is not only a means of satisfying the economic needs but also a measure of one’s power, prestige, independence, happiness and so on. Money can buy many things. It can satisfy biological needs (food, shelter, sex, recreation, etc.) as well as security, social and esteem needs.