Each company uses some form of analysis to determine pricing policy for its product or service. The price is the amount that customers must spend or are willing to pay for that product or service (list price).

Pricing Strategy: Meaning, Framework for Selecting Strategies and Conclusion

Contents:

- Meaning of Pricing Strategy

- Framework for Selecting Pricing Programs/Strategies

- Conclusion to Pricing Strategy

1. Meaning of Pricing Strategy:

Each company uses some form of analysis to determine pricing policy for its product or service. The price is the amount that customers must spend or are willing to pay for that product or service (list price). Many decisions surround that price determination. Prices require frequent review and depend on many factors, which might include the company’s objectives, market and environmental conditions, and competitive changes.

Prices can be an integral part of the marketing strategy for a product or a product-line and can influence demand in a variety of ways.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Managing price means, what level of price a firm should charge in order to implement (or at least be consistent with) the marketing strategy. It includes setting objectives; selecting appropriate strategy, including price cutting and discounting; and using several demand-and cost-oriented price-determining methods. Market-differentiated strategy considers pricing decisions in line with these factors.

# 2. Framework for Selecting Pricing Programs/Strategies:

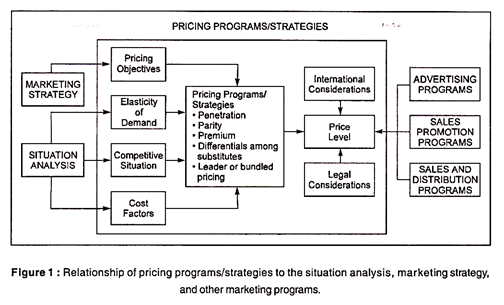

In line with the above, we present a framework for selecting pricing programs/strategies.

Basically the elements of our framework are as follows:

1. Establish the pricing objective.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

2. Analyse the price-elasticity of demand.

3. Identify key factors acting on price competition.

4. Estimate the relationship between price changes and volume, cost, and profit changes.

5. Based on the analyses of price-elasticity, competition, and cost-volume-profit relationships, establish the basic type of pricing program or strategy to use for the product being priced.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

6. Consider the impact of the planned pricing strategy on any product-line, substitutes or complements.

7. Determine if any legal limitations on pricing decisions exist or if any modifications are necessary for international markets.

For firms selling goods or services directly to their final customers, the process outlined above will result in the establishment of a list price. This is the basic price that the firm normally expects to receive. However, list prices are often modified by sales promotions (such as coupons and specials) and by sales and distribution arrangements that involve negotiated prices, cash or quantity discounts, or long-term contracts.

Pricing decisions must also reflect appropriate timing. The final price may also take into account the brand’s quality and advertising relative to competition.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The research studies on consumer businesses reveal that:

1. Brands with average relative quality but high advertising budgets are able to charge premium prices. Consumers apparently are willing to pay higher prices for known products than for unknown products.

2. Brands with high relative quality and high relative advertising obtain the highest prices. Conversely, brands with low quality and low advertising charge the lowest prices.

3. The positive relationship between high prices and high advertising holds most strongly in the later stages of the product life cycle, for market leaders, and for low-cost products.

1. Establishing Pricing Objectives:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

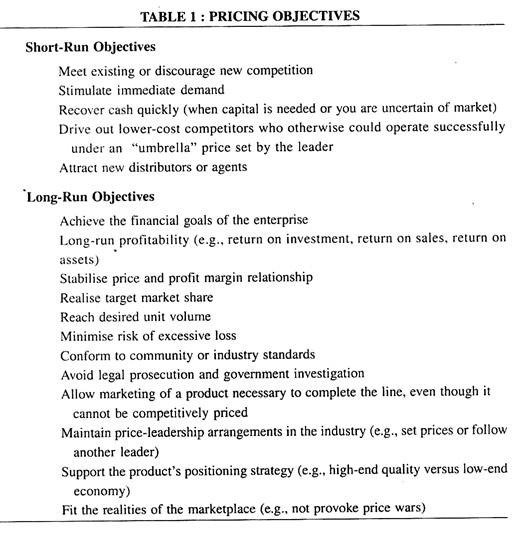

Price responses are most often made with such objectives in mind as improving margins and cash flows. Short-term and long-term profitability must be considered when determining pricing policies and objectives. Possible short-and long-run objectives are listed in Table 1.

A strategic option might consider giving customers more value for the money and beating their expectations with price. The idea can be further extended to a best-cost producer when the company meets the buyer’s expectations on quality, features, service, and performance.

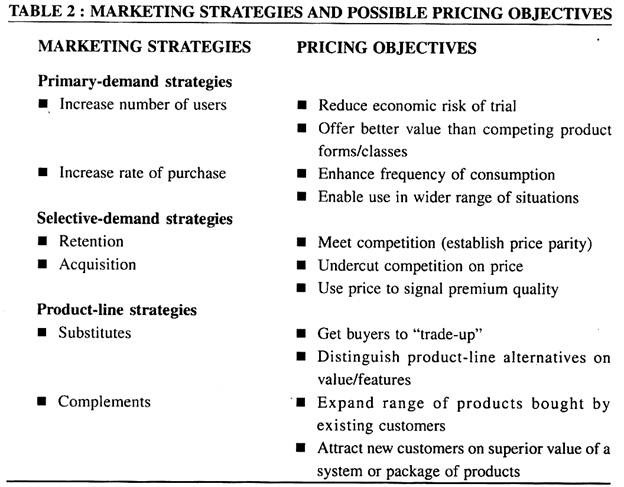

The purpose of any pricing program or strategy is to support the marketing strategy that has been developed for the product or product line. Pricing objectives specify how price is expected to help implement the marketing strategy. Table 2 lists the major types of marketing strategies and some pricing objectives that would typically be associated with each strategy type.

Primary-demand-based objectives are selected if the firm believes that price can be used to increase either the number of users or the rate of purchase. Especially in the introductory or growth stages of a product life cycle, lower prices may reduce the buyer’s perceived risk of trial. Or, lowering a price may enhance the relative value of one product form versus another.

An Example:

Lower prices for notebook computers have not only reduced the risks of trial but have also made the product relatively more attractive compared with conventional personal computers.

Alternatively, lower prices could be designed to enhance the rate of purchase either by increasing consumption frequency or by broadening the number of usage situations to include lower priority uses.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Two Examples:

Reduced prices of high-quality cuts of beef or goat may motivate people to consume more frequently. Lower long-distance telephone rates may lead people to make phone calls to friends they normally would write to.

Selective-demand-based objectives are those designed to support either a retention strategy or an acquisition strategy. Generally speaking, pricing designed to meet the competition will be used if a firm’s primary concern is to retain the existing customer base.

When the strategy is acquisition-oriented, the pricing objective may be to become the low-price alternative or to under-score a quality-based differentiation.

It should be noted, however, that meeting the competition is not necessarily an inappropriate objective for an acquisition strategy. A firm may want to compete on non-price factors and thus decide to match competitors’ prices in an effort to remove price as a consideration in making a choice.

Finally, product-line-based objectives are those that guide the pricing of a line of substitutes or of a product that has many complements. For substitutes, the objective will be either to encourage some buyers to consider more expensive models within a line (an important issue in pricing a line of automobiles) or to make quality distinctions very clear.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

An Example:

Most banks offer different facilities to distinguish account holder that have different balance requirements or cheque writing limits.

For complements, the primary objective may be to expand the range of products purchased by existing customers (When a bank offers a no-annual-fee credit card to its existing account holders.)

Alternatively, the objective may be to attract new customers through offering superior value on a system or package of new products.

An Example:

An appliance dealer may offer a free extended warranty on a new television set.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

However, managers should recognise that pricing objectives cannot be established simply from knowing the marketing strategy.

It may turn out that price will not be useful in implementing a marketing strategy because:

(i) Customers are not sensitive to price,

(ii) Competitors offset the pricing strategies by the price actions they take in response, or

(iii) The profitability consequences of a pricing strategy are unacceptable.

The purpose of setting a pricing objective is to identify the specific kind of impact on demand that management wants to achieve through pricing. The pricing strategy should result in a price level that will achieve the price objective (and thus help implement the marketing strategy) and at the same time ensure that the product’s target contribution will be achieved.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

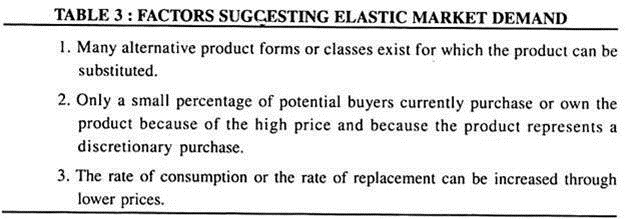

More fundamentally, managers cannot establish meaningful pricing objectives unless they believe that demand will be responsive to price. That is, managers cannot determine how price may contribute to a marketing strategy unless they have analysed the price- elasticity of demand.

2. Price-Elasticity of Demand-Analysis:

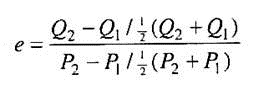

Because the effectiveness of any pricing strategy depends on the impact of a price change on demand, it is necessary to understand the extent to which unit sales will change in response to a change in price. The price-elasticity of demand explicitly takes this into account.

More specifically, price-elasticity of demand is measured by the percentage change in quantity divided by the percentage change in price.

Given an initial price P, and an initial quantity Q1, the elasticity of a change in price from P1 to P2 is calculated by:

If the elasticity measure e can be calculated, then management can predict the impact of the price change on revenue.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

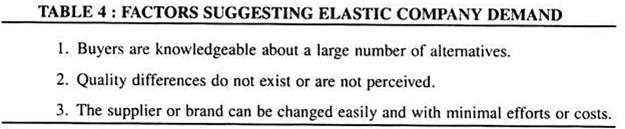

In making estimates of elasticity, however, managers need to distinguish carefully between elasticity of market demand and the elasticity of company (or brand) demand and to recognise that differences in elasticity may exist across segments within a market.

Marketers need to know how responsive demand would be to a change in price. The possibility of raising prices and increasing total revenue is attractive to marketing managers. This effect occurs when the demand is inelastic. Although price increases may result in unit volume reductions, the demand is inelastic if total revenue increases.

On the other hand, if total revenue decreases when the price increases, the demand is elastic. When demand is elastic, it is often assumed that the company can increase profits by lowering price.

Demand elasticities are affected by availability of substitutes, the importance of the- product in the buyer’s budget, and urgency of need. Also, differentiating the offering to make it less elastic allows the marketer to charge a higher price.

Market, Segment, and Company Elasticity:

Market elasticity indicates how total primary demand responds to a change in the average prices of all competitors. Company elasticity indicates the willingness of customers to shift brands or suppliers (or of new customers to choose a supplier) on the basis of price.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Marketers are not just interested in understanding total market demand, however. For most products, different buyers have different determinant attributes. So often there are substantial differences in the price-sensitivity of different buyers.

Whether a firm’s individual pricing strategy is effective, however, will depend on the company elasticity of demand. Even if industry prices decline, a given firm serving even the elastic non business market might conceivably experience inelastic demand if it could clearly differentiate its operations in terms of some other determinant attribute.

If so, that firm could continue to charge prices higher than its competitors’ without reducing profitability.

Managers should note that the distinction between market elasticity and company elasticity is directly related to the two major types of marketing strategies and pricing objectives discussed earlier.

Specifically, if a manager’s pricing objective is to increase rates of purchase for the product form or to increase demand among users (both of which reflect primary-demand strategies), then the manager should determine whether market demand is inelastic.

On the other hand, if the pricing objectives reflect selective-demand strategies (such as the retention or acquisition of customers), then managers should be concerned about the elasticity of company demand.

However, it is not necessary that demand be elastic in order to achieve a pricing objective. Managers may be very committed to retaining customers or to acquiring new customers when the product objective is to maintain share or to increase market share.

Often this commitment is so strong that managers will be willing to risk some reduction in total revenue in order to maintain (or in order to establish) a strong position in a market.

Additionally, recent research findings are available that provide other useful insights into the judgmental assessment of price-elasticity.

These findings result in the following generalisations:

1. A price change will have no effect on demand unless it is large enough to be noticeable, and (all other things being equal) the higher the price, the larger the price change must be to be noticed.

2. The further a brand’s price is from the average price for the product category, the more distinct it is from the competition and the less the price-elasticity is.

3. The lower a brand’s market share, the greater the price-elasticity (because a small change in units sold translates into a larger percentage change than is the case for large market-share brands or firms).

4. Market elasticity of demand is generally highest in the early stages of the product life cycle, and company or brand elasticity is generally highest in the later stages of the product life cycle (when technological differences are minimal).

3. Competitive Factors:

Where a marketing manager is concerned with market or company elasticity, competitors’ reactions to a price change must be considered. After all, the change in price is matched by all competitors, then no change in market share should result. In that event, the price cut will have no effect on selective demand. Accordingly, he should attempt to determine what competitors’ pricing reactions will be.

Usually, it will be useful to examine historical patterns of competitive behaviour in projecting price reactions. Some competitors may price their products primarily on the basis of costs.

These firms often do not shift their pricing policies over time; instead, they either price very competitively (if they are trying to take advantage of experience curves or economies of scale) or attempt to maintain consistent contribution margins and thus avoid direct price competition.

Additionally, by analysing competitors’ historical pricing behaviour marketing manager may obtain insights into the likely customer reaction to a price change. Specifically, if an industry has historically been characterised by extensive price cutting, buyers will more likely be price-sensitive because they will expect price differences.

Marketing managers can also use their knowledge of competitive strengths and weaknesses and of the degree of competitive intensity in an industry in predicting competitors’ responses. However, even when price is the decision issue at hand, they should assess non-price reactions as well as direct price reactions in a market because competitors’ non-price actions may influence price-elasticity.

4. Cost Factors:

The pricing implications are associated with economies of scale. Specifically, the gains from economies of scale are greatest when fixed costs represent a high proportion of total cost. (Of course, if a firm is already producing close to its capacity, the economies of scale are already fully realised; such firms have little to gain from reducing prices.)

In this context, the concept of break-even analysis attempts to consider both demand and costs, and economies of scale. It assists price setting by predicting profit levels at various price levels. This analysis shows how many units must be sold at selected prices to regain the contributions made to the product.

Profits are gains when volume exceeds the break-even points, and losses occur when volume fails to reach the break-even point. Management wants to charge a price that would cover at least the total production costs at a given level of production.

Marketing actions and profit positions are assessed using the break-even analysis. Information needed to make the assessment includes:

(1) The selling price for each unit;

(2) The total fixed cost, which consists of the sum of the fixed and variable costs for any given level of production; and

(3) An estimate of unit variable costs. Variable costs vary directly with the number of units produced.

The formula for determining the number of units to break even is as follows:

Unit break- even volume = Total fixed costs/Unit selling price – Unit variable costs

In many firms, current or anticipated average costs serve as the primary basis for pricing. Specifically, many firms use the cost-plus approach, in which the price is determined by taking the cost per unit and then adding an amount or percentage- target-contribution margin.

5. Types of Pricing Programs/Strategies:

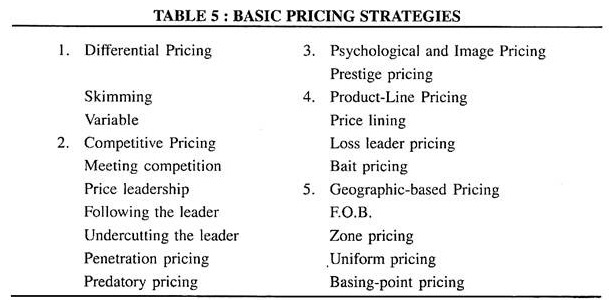

Marketing managers can select a pricing program or strategy once they have established the pricing objective and the elasticity of demand and once they have assessed their competitive and cost situation. Essentially, there are three basic types of strategies for pricing individual products: penetration, parity, and premium. However, some authors mention about five types of pricing strategies as per

6. Assessment of Factors for Pricing Decisions:

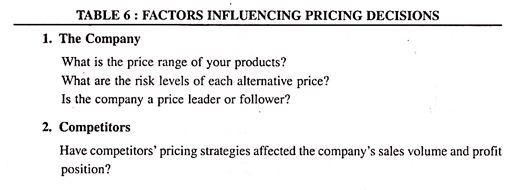

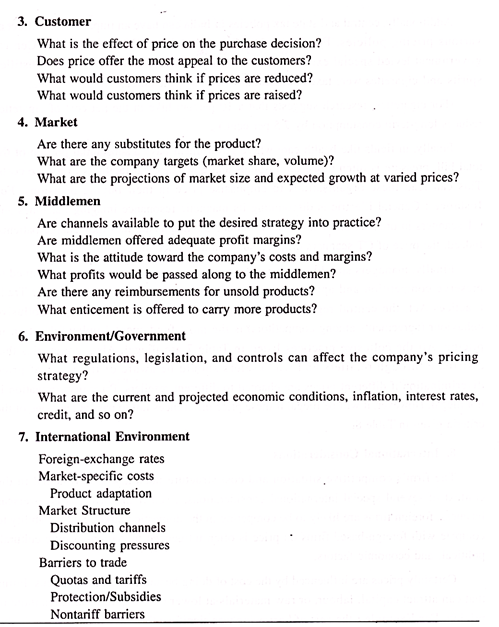

In making a choice of a pricing strategy or strategies, marketing manager needs to:

(1) Distinguish carefully between the different strategic options indicated in Table 5,

(2) Assess the firm’s position relative to the factors under each of the seven elements (that influence pricing decisions) stated in Table 6 and (3) consider the impact of the planned pricing strategy on any product-line, substitutes or complements.

7. Environment:

The political and legal environment can pose significant constraints on pricing decisions. Many of these constraints involve direct price regulation: Public utilities, airlines, trucking, and cable television are examples of industries that are or have been directly regulated with respect to prices.

Additionally, central and state tax policies in India can have an impact on the effect of various pricing policies. For Example: From the years 1990 to 1993 the Central government levied special excise taxes on luxury products and automobiles. Distilled spirits and cigarettes were taxed substantially, although the amount varies by state.

(For cigarettes, research suggests that a 10 percent hike in the net cost of cigarettes reduces long-term consumption by 7.5 per cent.)

Finally, in fields like health care where government pays a substantial portion of the total bill, pressure is often thrust on hospitals and other medical facilities to reduce costs. This can lead these organisations to emphasise price in their buying decisions.

For Instance: General Electric is discounting its magnetic resonance imaging machines and CT scanners in order to allow hospitals to reduce the diagnostic fees they charge patients. Indeed, the price of CT scanners dropped substantially since the early 1990s.

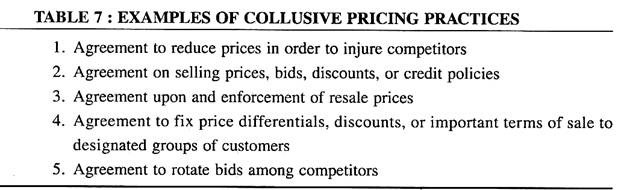

Finally, managers should be aware of government regulations that are designed to preserve competition and apply to virtually all industries. Based on the Unfair Trade Practices Act, the central regulations limit pricing behaviour in two ways. Collusive behaviour (agreements among competitors) is the most fundamental unlawful action in pricing.

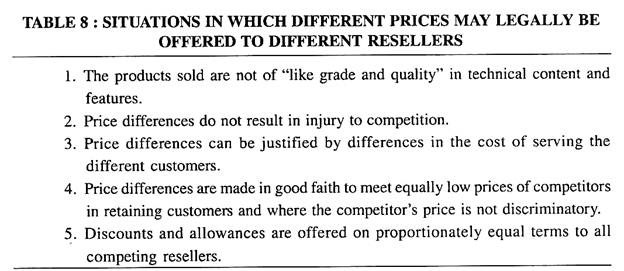

All the collusive practices listed in Table 7 are illegal. Also, companies that distribute through retailers and wholesalers should be aware of the issue of price discrimination if different prices are charged to different resellers. Price discrimination is not illegal. However, it will be illegal if these price differences fail to pass at least one of the criteria given in Table 8.

8. International Considerations:

The firm’s competitive situation and cost structure must also be evaluated in the context of several special international considerations. Even if the firm has no overseas business, foreign firms are likely to be competing in the domestic market, and the ability to complete with foreign-based firms on price is often influenced by nation-specific cultural, political, and economic factors.

Certainly prices are influenced by the cost of doing business in various nations. Firms that can attract capital, labour, or raw materials at lower cost will have an advantage in pricing.

For Example: the cost of borrowing was significantly lower in Japan than in the United States during the 1980s, allowing Japanese firms to price products slightly lower to get the same profit return as their U.S. counterparts.

Additionally, when exporting products to other nations, tariffs or import fees must be considered. It is still not unusual to find tariffs of 20 or 30 per cent applied to selected imported goods when a nation is trying to protect a domestic industry from price competition.

The most problematic global force for business is the currency exchange rate. The rates at which currencies of different nationals are exchanged fluctuate over time, and a sharp unexpected change (or even a significant long-term change) can create problems for a firm.

# 3. Conclusion to Pricing Strategy:

Management’s recognition of the importance of price decisions has increased in recent years. Deregulation, greater international competition, changes in technology, and occasionally inflation has all created changes in the patterns of price competition in one industry or another.

However, the process of developing a basic pricing program or strategy and arriving at a specific price remains a difficult one. However, by employing the process that this chapter and case studies have suggested, managers should be able to devise a pricing strategy that is consistent with their marketing strategy.

While the pricing program may be modified by sales-promotion programs and by sales and distribution programs, the basic role that pricing will play in implementing a marketing strategy should be determined by:

(1) Establishing clear pricing objectives,

(2) analysing price-elasticity, competition, and costs, and

(3) Considering political-legal and international constraints.

Figure 1 summarises these steps and provides an overview of the relationships among them.

While the pricing program or strategy may not be a major component in the marketing strategy of every firm, it is certainly a critical component of it.