Everything you need to know about the supply chain management.

Supply chain management (SCM) is the oversight of materials, information, and finances as they move in a process from supplier to manufacturer to wholesaler to retailer to consumer.

Supply chain management involves coordinating and integrating these flows both within and among companies. It is said that the ultimate goal of any effective supply chain management system is to reduce inventory with the assumption that products are available when needed.

As a solution for successful supply chain management, sophisticated software systems with Web interfaces are competing with Web-based application service providers (ASP) who promise to provide part or all of the SCM service for companies who rent their service.

Supply chain management refers to the management of material and information flow in a supply chain to provide the highest degree of customer satisfaction at the lowest possible cost. It requires the commitment of supply chain partners to work closely to coordinate order generation, order taking and order fulfillment.

Learn about:

1. Introduction to Supply Chain Management 2. Meaning of Supply Chain Management 3. Definitions 4. Implementation 5. Decision Phases

6. Process View of a Supply Chain 7. Macro Processes in a Firm 8. Decision Areas 9. Importance 10. Problems.

Supply Chain Management: Introduction, Meaning, Definitions, Process and Problems

Contents:

- Introduction to Supply Chain Management

- Meaning of Supply Chain Management

- Definitions of Supply Chain Management

- Implementation of Supply Chain Management

- Decision Phases of Supply Chain Management

- Process View of a Supply Chain

- Macro Processes in a Firm

- Decision Areas of Supply Chain Management

- Importance of Supply Chain Management

- Problems of Supply Chain Management

Supply Chain Management – Introduction

Supply chain management (SCM) is the process of planning, implementing, and controlling the operations of the supply chain as efficiently as possible. Supply Chain Management spans all movement and storage of raw materials, work-in- process inventory, and finished goods from point-of-origin to point-of-consumption. The term supply chain management was coined by consultant Keith Oliver, of strategy consulting firm Booz Allen Hamilton in 1982.

The definition one America professional association put forward is that Supply Chain Management encompasses the planning and management of all activities involved in sourcing, procurement, conversion, and logistics management activities. Importantly, it also includes coordination and collaboration with channel partners, which can be suppliers, intermediaries, third- party service providers, and customers. In essence, Supply Chain Management integrates supply and demand management within and across companies.

Some experts distinguish Supply Chain Management and logistics, while others consider the terms to be interchangeable. Supply Chain Management is also a category of software products. Supply chain event management (abbreviated as SCEM) is a consideration of all possible occurring events and factors that can cause a disruption in a supply chain. With. SCEM possible scenarios can be created and solutions can be planned.

Organizations increasingly find that they must rely on effective supply chains, or networks, to successfully compete in the global market and networked economy. In Peter Drucker’s (1998) management’s new paradigms, this concept of business relationships extends beyond traditional enterprise boundaries and seeks to organize entire business processes throughout a value chain of multiple companies.

During the past decades, globalisation, outsourcing and information technology have enabled many organisations such as Dell and Hewlett Packard, to successfully operate solid collaborative supply networks in which each specialized business partner focuses on only a few key strategic activities. This inter-organizational supply network can be acknowledged as a new form of organization. However, with the complicated interactions among the players, the network structure fits neither “market” nor “hierarchy” categories.

It is not clear what kind of performance impacts different supply network structures could have on firms, and little is known about the coordination conditions and trade-offs that may exist among the players. From a system’s point of view, a complex network structure can be decomposed into individual component firms.

Traditionally, companies in a supply network concentrate on the inputs and outputs of the processes, with little concern for the internal management working of other individual players. Therefore, the choice of internal management control structure is known to impact local firm performance.

In the 21st century, there have been a few changes in business environment that have contributed to the development of supply chain networks. First, as an outcome of globalisation and proliferation of multinational companies, joint ventures, strategic alliances and business partnerships were found to be significant success factors, following the earlier “Just-In-Time”, “Lean Management” and “Agile Manufacturing” practices.

Second, technological changes, particularly the dramatic fall in information communication costs, a paramount component of transaction costs, has led to changes in coordination among the members of the supply chain network. Many researchers have recognized these kinds of supply network structure as a new organization form, using terms such as “Keiretsu”, “Extended Enterprise”, “Virtual Corporation”, Global Production Network”, and “Next Generation Manufacturing System”.

In general, such a structure can be defined as “a group of semi- independent organizations, each with their capabilities, which collaborate in ever- changing constellations to serve one or more markets in order to achieve some business goal specific to that collaboration”.

Successful SCM requires a change from managing individual functions to integrating activities into key supply chain processes. An example scenario, the purchasing department places orders as requirements become appropriate. Marketing, responding to customer demand, communicates with several distributors and retailers, and attempts to satisfy this demand. Shared information between supply chain partners can only be fully leveraged through process integration.

Supply chain business process integration involves collaborative work between buyers and suppliers, joint product development, common systems and shared information. According to Lambert and Cooper (2000) operating an integrated supply chain requires continuous information flows, which in turn assist to achieve the best product flows.

However, in many companies, management has reached the conclusion that optimizing the product flows cannot be accomplished without implementing a process approach to the business.

Supply Chain Management – Meaning

In supply chain management the firm uses a series of value-adding activities to connect the company’s supply side with its demand side. This approach views the supply chain of the entire extended enterprise, beginning with the supplier’s supplier and ending with consumers, or end users. The perspective encompasses all products, information, and funds that form one cohesive link to acquire, purchase, convert / manufacture, assemble, and distribute goods and services to the ultimate consumer.

The implementation effects of such supply chain management systems can be major. Efficient supply chain design can increase customer satisfaction and save money at the same time. On an industry-wide basis, research conducted by Coopers and Lybrand, before its 1998 merger with Price Waterhouse, indicates that the use of such tools in the structuring of supplier relations could reduce operating costs of the European grocery industry by $27 billion per year, with savings equivalent to a 5.7 percent reduction in price.

Clearly, the use of such strategic tools is crucial to develop and maintain key competitive advantages.

Underlying effective supply chain management is the development of a logistics system that controls the flow of materials into, though, and out of the corporation. Due to the systems approach, the firm explicitly recognizes and coordinates the linkages among the traditionally separate logistics components within the corporation, which are production, transportation facility, inventory, and communication decisions.

By recognizing the logistics interaction with outside organizations and individuals, such as suppliers and customers, the firm is able to create a mutual purpose for all partners in the areas of performance, quality, and timing.

As a result of implementing a logistics system, the firm can develop just-in-time (JIT) delivery for lower inventory cost, electronic data interchange (EDI) for more efficient order processing, and early supplier involvement (ESI) for better planning of product movement. The logistics effort has two parts – materials management and physical distribution management.

Materials management controls the movement through the production processes. It takes in raw materials and schedules them through the various processes until the final product is placed into the finished goods warehouse. Physical distribution management deals with the inflow of products from suppliers and the movement of the firm’s finished product to its customers. In both phases, movement is seen within the context of the entire process.

Stationary periods (storage and inventory) are therefore included. The basic goal is the effective coordination of both materials and physical distribution management to result in maximum cost-effectiveness while maintaining service goals and requirements. In the words of the director of international logistics operations at General Motors, the purpose of logistics is “to plan cost-effective systems for future use, attempt to eliminate duplication of effort, and determine where distribution policy is lacking or inappropriate.

Emphasis is placed on consolidating existing movements, planning new systems, identifying useful ideas, techniques, or experiences, and working with various divisions’ toward implementation of beneficial changes.”

Supply Chain Management – Definitions

The supply chain starts at the source point of raw materials, components and parts. It follows all these materials through from the point of supply to the customer. This chain includes all suppliers for all parts of the final product. It encompasses all materials and information that moves up and down the chain.

Logistics is the portion of the supply chain that deals directly with the transportation and warehousing of goods and materials.

It is a network of facilities including material flow from suppliers and their “upstream” suppliers at all levels. Transformation of materials into semi-finished and finished products, and distribution of products to customers and their “downstream” customers at all levels. Briefly then, L&SCM is enshrined in the 5Rs — making the Right Product available at the Right Place, at the Right Time, at the Right Cost and in the Right Quality.

According to Cooper, Lambert, and Pagn, the following is a formal definition of supply chain management, “SMC is the integration of business processes from end user through suppliers that provides products, services and information that add values for customers.”

A supply chain consists of all parties involved, directly or indirectly, in fulfilling a customer request. A typical supply chain may involve a variety of stages. These supply chain stages include –

i. Customers

ii. Retailers

iii. Wholesalers /Distributors

iv. Manufacturers

v. Component/Raw material suppliers.

The appropriate design of the supply chain and the number of stages will depend on both the customer’s needs and the roles of the stages involved.

The objective of every supply chain is to maximize the overall value generated. Today companies are giving Logistics & SCM due importance because of two reasons- cost control and retaining markets and both these factors are crucial to defending bottom lines.

Supply chain management includes the management of material and information between its movements from source to final consumer. This includes all logistics, materials handling and purchasing. The goal of the management is to increase the efficiency of its function to the maximum extent and lower the cost to the ultimate extent so that the final output is either a lowered price for the end customer, or a higher profit for the organisation.

Supply Chain Management has been defined as “the management of a network of all business processes and activities involving procurement of raw materials, manufacturing and distribution management of finished goods”.

Another definition states that, “Supply chain management is the flow of goods, services, information and money from the source of materials all the way to the consumer”.

Supply Chain Management is also called the art of management of providing the Right Product, At the Right Time, Right Place and at the Right Cost to the Customer.

According to the Council of Supply Chain Management Professionals, “Supply Chain Management encompasses the planning and management of all activities involved in sourcing and procurement, conversion, and all Logistics Management Activities”. Importantly, it also includes coordination and collaboration with channel partners, which can be suppliers, intermediaries, third party service providers, and customers.

Supply Chain Management – Implementation

The key supply chain processes stated by Lambert (2004) are:

(i) Customer relationship management

(ii) Customer service management

(iii) Demand management

(iv) Order fulfillment

(v) Manufacturing flow management

(vi) Supplier relationship management

(vii) Product development and commercialization

(viii) Returns management

Supply Chain Management is so well defined, its components are almost a chant- plan, source, make, deliver, return. Repeat forty times and fall into a stupor. Despite its soporific powers, these five components are a mantra to any company that delivers product to customers. They have the power to make or break your relationships with these customers. These five components are as clearly marked and well-known as they are due to the SCOR model developed by the Supply Chain Council.

SCOR — the Supply Chain Operations Reference model — as of this writing is at version 6.0 and is a highly refined, well-optimised standard that combines supply chain-only business processes with key metrics and benchmarks, and comes up with a set of best practices that have been put to practical use by the Supply Chain Council’s members. The procedure the Supply Chain Council uses to create the model is interesting on the face of it, and worth understanding as one that is useful in developing any standard.

The steps:

1. Identify the “as is” state of a supply chain related business process;

2. Identify the “to be” state of the same process; and

3. Quantify that against the operational practices of existing similar companies (usually members)

4. Extract a series of world class processes, a.k.a. best practices; and

5. Characterise these management procedures and the associated software solutions that result in the best practices.

Planning is exactly what it sounds like. Make determinations how to build, extend, define, or determine the supply chain and all its components.

(i) Balance resources with requirements and establish/communicate plans for the whole supply chain, including return and the execution processes of source, make, and deliver.

(ii) Management of business rules, supply chain performance, data collection, inventory, capital assets, transportation, planning configuration, and regulatory requirements and compliance.

(iii) Align the supply chain unit plan with the financial plan.

This is all the pieces needed to find the optimal suppliers that will provide you with the appropriate goods and services.

(i) Schedule deliveries; receive, verify, and transfer product; and authorize supplier payments.

(ii) Identify and select supply sources when not predetermined, as for engineer-to-order product.

(iii) Manage business rules, assess supplier performance, and maintain data.

(iv) Manage inventory, capital assets, incoming product, supplier network, import/export requirements, and supplier agreements.

Again, straightforward (if only the entire IT world were as clear and simple as the supply chain definitions). How to produce the goods that you need to get to the customer.

(i) Schedule production activities, issue product, produce and test, package, stage product, product to deliver.

(ii) Finalise engineering for engineer-to-order product.

(iii) Manage rules, performance, data, in-process products (WIP), equipment and facilities, transportation, production network, and regulatory compliance for production.

We all know this one. What does it take to get the planned, sourced, made goods to the customer?

(i) All order management steps from processing customer inquiries and quotes to routing shipments and selecting carriers.

(ii) Warehouse management from receiving and picking product to loading and shipping product.

(iii) Receive and verify product at customer site and install, if necessary.

(iv) Invoice customer.

(v) Manage deliver business rules, performance, information, finished product inventories, capital assets, transportation, product lifecycle, and import/ export requirements.

We all know this one too. What does it take to get the planned, sourced, made, delivered goods back to the producer or supplier?

(i) All return defective product steps from authorising return; scheduling product return; receiving, verifying, and disposition of defective product; and return replacement or credit.

(ii) Return MRO product steps from authorising and scheduling return, determining product condition, transferring product, verifying product condition, disposition, and request return authorisation.

(iii) Return excess product steps including identifying excess inventory, scheduling shipment, receiving returns, approving request authorisation, receiving excess product return in source, verifying excess, and recover and disposition of excess product.

(iv) Manage return business rules, performance, data collection, return inventory, capital assets, transportation, network configuration, and regulatory requirements and compliance.

It is a clear definition of what concerns supply chain and how the supply chain works. What is interesting, though, unspoken, is that this is a highly customer-sensitive set of actions. Think about it. Plan (by employees), source (suppliers), make (employees, suppliers), deliver (to paying customers, partners), return (from paying customers, partners, suppliers).

No matter how much you automate a so-called back-office set of processes, the ultimate target is the 21st century customer. SCM is a customer issue, not just an anonymous back-office process, there for the stream-lining. There are live people involved in the creation and movement of inanimate products.

Organizations that deal with the production and distribution of physical goods would definitely follow a pre-set process that enables the coordination and control of the flow of goods and information through the organization. Often this system is not adequately integrated with the upstream or downstream suppliers who are connected in this flow. Often organizations would work in isolation with complete lack of coordination or harmony.

Or else, organizations were known to have rudimentary interfaces with the other organizations linked in the flow of goods and information. However, such basic interfaces cannot achieve much other than small improvements such as a speedier flow or more accurate transaction processing.

Only when organizations follow a complete SCM programme, is there complete harmonization of the processes of the interlinked firms required to reap full benefits of maximum speed and accuracy of supply.

The exact process or characteristic of SCM, however, requires a better description. It is also important to appreciate that SCM is not just a re-engineering of processes, but adoption of a complete management strategy. This strategy includes principles and strategic components, as well as tactics. Organizations that implement SCM therefore would embrace the principles of SCM, adopt the strategies and achieve strategic implementation, through tactics of SCM.

Supply Chain Management – Decision Phases: Strategic or Design, Tactical/Planning and Operations Level

Supply chain management decisions are often said to belong to one of the following three levels—strategic, tactical, or operational. The decisions on a higher level will set the conditions under which the lower level decisions are made.

1. Strategic or Design Level:

At the strategic or design level, long-term decisions related to the supply chain’s configuration are made. Some of them include resource allocation and the performance of processes at each stage.

Strategic decisions made by the companies include those pertaining to location, capacities of production, inventory, warehousing facilities, products to be manufactured, modes of transportation, and the type of information system to be utilized. A firm must ensure that the supply chain configuration supports its strategic objectives during this phase.

Location decisions are concerned with the size, number, and geographic location of the supply chain entities, such as plants, inventories, or distribution centres. The production decisions are meant to determine the product mix to be manufactured, procurement locations, supplies, etc. Inventory decisions are concerned with the way of managing inventories throughout the supply chain.

Decisions made on the strategic level are interrelated; for example, decisions about the mode of transport are influenced by decisions on geographical placement of plants and warehouses, and inventory policies are influenced by the choice of suppliers and production locations.

Modeling and simulation is frequently used for analysing these interrelations, and the impact of making strategic level changes in the supply chain. For example, Dell’s decisions regarding the location and capacity of its manufacturing facilities, warehouses, and supply sources are all design or strategic decisions.

While taking these decisions, the company must take into account uncertainty in the market conditions over the next few years.

2. Tactical/Planning Level:

For decisions made during this phase, the time frame considered is a quarter to a year. Therefore, the supply chain’s configuration as determined in the strategic phase establishes constraints within which planning must be done. Companies start the planning phase by forecasting demand in different markets for the coming year.

Planning includes decisions regarding the markets that will be supplied with the goods, the locations from where they would be supplied, the subcontracting or manufacturing, the inventory policies to be followed, and the timing and size of marketing promotions. For example, Dell’s planning decisions involves identification of specific production facilities and target production quantities at different locations.

Planning establishes parameters within which a supply chain must include uncertainty in demand, exchange rates, and competition over this time horizon in their decisions. As a result of the planning phase, companies define a set of operating policies that govern short-term operations.

3. Operations Level:

The time frame of decisions at the operational level is a week or a day. During this phase companies make decisions regarding individual customer’s orders. At the operational level, supply chain configuration is considered fixed and planning policies are already defined and, hence, the goal of supply chain operations is to handle incoming customer orders in the best possible manner.

In this phase, firms allocate inventory or production outputs to individual orders, set a date when an order is to be filled, generate pick-up lists at a warehouse, allocate an order to a particular shopping mode and shipment, set delivery schedules of trucks, and place replenishment orders.

There is, thus, less uncertainty in the demand information as the decisions are short-term. The design, planning, and operations decisions of a supply chain have a strong impact on profitability and success of a business enterprise.

Supply Chain Management – Process View of a Supply Chain: Customer Order, Replenishment, Manufacturing and Procurement Cycle

There are two different ways to view the processes performed in a supply chain—the cycle view and the push-pull view. The processes in a supply chain are divided into a series of cycles in the cycle view. Each cycle is performed at the interface between two successive stages of a supply chain.

The processes in a supply chain are divided into two categories in the push-pull view depending on whether they are executed in response to a customer order or in anticipation of customer orders. Pull processes are initiated by a customer order whereas push processes are initiated and performed in anticipation of customers orders.

Cycle View of Supply Chain Process:

The supply chain processes can be broken down into the following four cycles – (1) customer order cycle; (2) replenishment cycle; (3) manufacturing cycle; and (4) procurement cycle. Each cycle occurs at the interface between two successive stages of the supply chain.

(1) Customer Order Cycle:

The customer order cycle occurs at the customer-retailer interface and includes all those processes directly involved in receiving and filling the customer’s order. Typically, the customer initiates this cycle at a retailer site and the cycle primarily involves meeting the customer’s demand. The retailer’s interaction with the customer starts when the customer arrives or a contact is initiated and ends when the customer receives the order.

The processes involved in the customer order cycle include:

i. Customer arrival – It refers to the customer’s arrival at the location where he can make choices and arrive at a decision regarding a purchase.

ii. Customer order – It refers to the customer informing the retailer about the products he wants to purchase and the retailer allocating the products to customers.

iii. Customer order fulfillment – During this process, the customer’s order is met with and the product is delivered.

iv. Customer order receiving – During this process, the customer receives the order and takes ownership.

(2) Replenishment Cycle:

The replenishment cycle occurs at the retailer-distributor interface and includes all processes involved in replenishing retailer inventory. It is initiated when a retailer places an order to replenish inventories to meet future demand. The replenishment cycle is similar to the customer order cycle except that the retailer is now the customer.

The objective of the replenishment cycle is to replenish inventories at the retailer at minimum cost while providing high product availability.

The processes involved in the replenishment cycle include:

i. Retail order trigger – As the retailer tries to meet the customer’s demand, the inventory is depleted and must be replenished to meet future demand.

ii. Retail order entry – This process is similar to customer order entry at the retailer. The only difference is that the retailer is now the customer placing the order that is conveyed to the distributor.

iii. Retail order fulfillment – Once the replenishment order arrives at a retailer, the retailer must receive it physically and update all inventory records.

iv. Retail order receiving – This process refers to the movement of the product and related information from the distributor to the retailer and the flow of funds from the retailer to the distributor.

(3) Manufacturing Cycle:

The manufacturing cycle typically occurs during the distributor- manufacturer (or retailer-manufacturer) interface and includes all processes involved in replenishing distributor (or retailer) inventory.

The manufacturing cycle is triggered by customer orders (Dell), replenishment orders from a retailer or distributor (Wal- Mart ordering from P&G), or by the forecast of customer demand and current product availability in the manufacturer’s finished-goods warehouse.

The processes involved in the manufacturing cycle include the following:

i. Order arrival – During this process, a finished-goods warehouse or distributor sets a replenishment order trigger based on the forecast of future demand and current product inventories.

ii. Production scheduling – This process is similar to the order entry process in the replenishment cycle where the inventory is allocated to an order. During the production scheduling process, orders (or forecasted orders) are allocated to a production plan. Given the desired production quantities for each product, the manufacturer must decide on the precise production sequence.

iii. Manufacturing and shipping – This process is equivalent to the order fulfilment process described in the replenishment cycle. During the manufacturing phase of the process, the manufacturer produces to the production schedule. During the shipping phase of this process, the product is shipped to the customer, retailer, distributor, or finished- goods warehouse.

iv. Receiving at the distributor, retailer, or customer end – In this process, the product is received at the distributor, finished-goods warehouse, retailer, or customer and inventory records are updated. Other processes related to storage and fund transfers also take place.

(4) Procurement Cycle:

The procurement cycle occurs at the manufacturer-supplier interface and includes all processes necessary to ensure that materials are available for manufacturing to occur according to schedule. During the procurement cycle, the manufacturer orders the components from the suppliers who replenish the component inventories.

The relationship is quite similar to that between a distributor and manufacturer with one significant difference. The retailer- distributor orders are triggered by uncertain customer demand, but component orders can be determined precisely once the manufacturer has decided the production schedule. The orders for components depend upon the production schedule.

Thus, it is important for suppliers to be linked to the manufacturer’s production schedule. Of course, if a supplier’s lead times are long, the supplier has to produce to forecast because the manufacturer’s production schedule may not be fixed that far in advance.

In practice, there may be several tiers of suppliers, each producing a component for the next tier. A similar cycle would then flow back from one stage to the next.

Supply Chain Management – Macro Processes in a Firm: Customer Relationship Management, Internal Supply Chain Management and Supply Relationship Management

All supply chain processes in a firm can be classified into three macro processes— customer relationship management (CRM), internal supply chain management (ISCM), and supply relationship management (SRM).

1. Customer relationship management (CRM) – All processes that focus on the interface between the firm and its customers.

2. Internal supply chain management (ISCM) – All processes that are internal to the firm.

3. Supply relationship management (SRM) – All processes that focus on the interface between the firm and its suppliers.

These three macro processes manage the flow of information, product, and funds required to generate, receive, and fulfil a customer’s request. The CRM macro process aims to generate customer demand and facilitate the placement and tracking of orders. It includes processes such as marketing, sales, order management, and call centre management.

The ISCM process aims to fulfil the demands generated by the CRM process. These processes include the planning of internal production and storage capacity, preparation of demand and supply plans, and internal fulfilment of actual orders.

The SRM macro process aims to arrange for and manage supply sources for various goods and services. Processes include the evaluation and selection of suppliers, negotiation of supply terms, and communication regarding new products and orders with the suppliers.

Supply Chain Coordination and Bullwhip Effect:

Supply chain coordination functions effectively as long as all stages of the chain take actions that together increase total supply chain profits. Each participant (phase) of the chain should balance its actions to other participants’ and the supply chain in general and make decisions that are beneficial to the whole chain.

If the coordination is weak or does not exist at all, a conflict of objectives tends to appear among the participants, who try to maximize personal profits. If the relevant information for some reason can be unreachable to the participants in the chain or the information can get deformed in non-linear activities of some parts of chain, it can lead to irregular comprehension.

All these lead to the so-called bullwhip effect resulting from information disorder or increasing fluctuations in orders as they move up within a supply chain from retailers to wholesalers to manufacturers to suppliers. Different chain phases have different calculations of demand quantity, thus, the longer the chain between the retailer and wholesaler, the bigger the demand variation.

This distorts demand information within the supply chain, with different stages having very different estimates of what the demand looks like. The result is the loss of supply chain coordination.

P&G has observed the presence of the bullwhip effect in the supply chain for diapers. The company found that raw material orders from P&G to its suppliers fluctuated significantly over time. Further down the chain, when sales at retail stores were studied, it was found that the fluctuations were small.

It is reasonable to assume that the consumers of diapers at the last stage of supply chain used them at a steady rate. Although consumption of the end product was stable, order for raw materials were highly variable, increasing costs and making it difficult for supply to match demand.

It is also seen that apparel and grocery industry have shown a similar phenomenon; the fluctuation in orders increases as we move upstream in the supply chain from retail to manufacturing. There may be a lack of coordination if each stage of the supply chain only optimizes its local objective without considering the impact on the complete chain. It also results in information distortion between the different stages of the supply chain.

A variation in information demands leads to increased production expenses and supply chain expenses in an effort to deliver the ordered quantity in time. Manufacturers accomplish demanded capacity and production but when the orders come to a downstream level, they end up with surplus capacity and inventory.

The bullwhip effect affects the costs related to manufacturing, inventory, replenishment lead time, transportation, labour, product availability, and relationships across the supply chain.

i. Manufacturing cost – The bullwhip effect increases manufacturing cost in the supply chain.

ii. Inventory cost – To handle the increased variability of demand, a company has to carry an increased level of inventory than what is required in the absence of bullwhip effect. Accordingly, the warehouse space is more occupied, all of which leads to an increase in holding or carrying costs of storage services.

iii. Replenishment lead time – Prolongs the lead time—the time period from the moment of purchasing to the moment of receiving the order—because of scheduling difficulty.

iv. Transportation cost – The bullwhip effect increases transportation costs within a supply chain. This is due to disorders in the orders being met, which results in fluctuations in transportation requirements over time where a situation arises that requires the maintenance of a surplus transportation capacity to cover the higher demand periods.

v. Labour cost – The bullwhip effect increases labour costs associated with shipping and receiving in the supply chain.

vi. Product availability – The bullwhip effect decreases the level of product availability, which can lead to deficiency of retail inventory when the retailers run out of stock. This results in lost sales for the supply chain and is due to the large fluctuation of orders, which makes it harder to supply all distributors’ and retailers’ orders on time.

vii. Relationships across the supply chain – The bullwhip effect negatively impacts performance at every stage and, thus, hurts the relationships between different stages of the supply chain. It also leads to loss of trust between different stages and makes any potential coordination efforts difficult.

Thus, the bullwhip effect makes a supply chain inefficient by increasing costs and decreasing responsiveness. It reduces the profitability of a supply chain by making it more expensive to provide a given level of product availability.

Any factor that leads to either local optimization by different stages of the supply chain or an increase in information distortion and variability within the supply chain is an obstacle to coordination. The major obstacles relate to incentives, information processing, operational issues, pricing, and behavioural issues.

i. Incentive Obstacles:

A situation in which incentives are offered at different stages or to participants in a supply chain leading to actions that increase variability and reduce total supply chain profits. These focus only on the local impact of an action and result in decisions that do not maximize total supply chain profits.

ii. Information Processing Obstacles:

Situations in which demand information is distorted due to movement across different stages of the supply chain and lack of coordination. It leads to increased variability in orders within the supply chain.

Demand forecasting based on the stream of orders received from the downstream stage results in a magnification of fluctuations in demand as we move up the supply chain from the retailer to the manufacturer. Lack of information sharing between stages of the supply chain magnifies the bullwhip effect.

iii. Operational Obstacles:

Actions taken in the course of placing and filling orders that lead to an increase in variability.

iv. Pricing Obstacles:

Situations in which the pricing policies for a product (lot-size- based quantity discounts and price fluctuations) leads to an increase in variability of orders placed. This is due to low-size-based discounts which increase the size of orders being placed. This magnifies the bullwhip effect.

v. Behavioural Obstacles:

It refers to learning problems within organizations that contribute to the bullwhip effect. These problems are related to the structure of the supply chain and the communication between different stages. This is due to the local optimization by different stages of the supply chain. Lack of trust between different partners and different stages of the supply chain lead to fluctuations and the successive stages becomes enemies rather than partners.

Companies focus on building supply chains to deliver the goods and services to consumers as quickly and inexpensively as possible. They also create teams, streamline processes, lay down the technologies, and invest in shared infrastructure. All those companies and initiatives are persistently aimed at greater speed and cost-effectiveness. The aims of the companies change when business is booming.

Managers concentrate on maximizing speed during boom time. Firms desperately try to minimize the supply costs during recession. Top-performing supply chains possess three very different qualities.

They are:

1. Great supply chains are agile. They react speedily to sudden changes in demand or supply.

2. They adapt over time as market structures and strategies evolve.

3. They align the interests of all the firms in supply network so that companies optimize the chain’s performance when they maximize their interests.

Only supply chains that are agile, adaptable, and aligned provide companies with sustainable competitive advantage. The agility and alignment factors emphasize the relationships’ importance in the supply chain.

Supply Chain Management – 5 Main Decision Areas: Production, Transportation, Facility, Inventory and Communications Decisions

Decision Area # 1. Production Decisions:

In the context of the distribution function, production decisions concern issues such as the quantity in each production batch and the lead time required for production. Production of a good can be continuous, as in an oil refinery or on a car assembly line. In these cases the whole production process has to be matched to demand. Very expensive mistakes can be made if the capacity installed turns out to be greater than demand; this results in frequent shutdowns.

Production is typically “batched” into specific production runs. The size of the production order, and the frequency with which the order is placed, is a matter for calculation on two separate fronts. The first refers to economies of scale. There is a cost overhead involved in placing every order, so the number of orders placed should be minimized. At the same time there is an ongoing cost involved in holding stock, and thus the amount of stock should also be minimized.

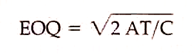

Needless to say, these two factors work in opposition. The equation that determines the EOQ (economic order quantity) is –

Where A is the cost of placing the order, T is the expected throughput in the time to the next order, and C is the unit cost of storing an item over the period until the next order is received.

The second major consideration in determining batch size and frequency concerns the buffer stock to be held to cope with variations in demand. Depending on the known pattern of demand, the optimal size of this buffer stock can be statistically calculated.

All these considerations, however, deal only with the status quo and do not address the distribution processes. That is where the coordination of activities with suppliers and customers can play a major role. For example, because the Wrangler jeans company receives precise, ongoing information about purchase levels (in terms of quantity, style, and sizes) from its major retail clients, the firm can plan its own purchasing and production more efficiently and thus offer a better price.

Similarly, if customers provide real-time information on their needs, the producer can be more efficient in scheduling production. In both instances, the degree of uncertainty is reduced, and the extent of mutual trust is increased.

To achieve these benefits, the firm has to invest substantially in building a system relationship and providing for information exchange. Clearly such investment is viable only if it is driven by a long-term perspective. However, the results show that the investment may well be worthwhile, as its benefits can far exceed the results of efficient internal management alone.

For example, typical savings from integrating the supply chain include the liberation of 50 percent of working capital, a 30 percent reduction in operating costs, and a sizable reduction in fixed assets. UPS Aviation Technologies, a subsidiary of United Parcel Service, used EDI to reduce the administrative time necessary for creating and sending purchase orders by 67 percent and reduced order processing time by 30 percent. With the Internet offering a lower-cost alternative to the development of private value-added networks, such collaboration is expected to increase markedly.

Decision Area # 2. Transportation Decisions:

Coordinating the transportation of products is a major operation. The investment is substantial, and the specialized management of the personnel and resources involved can be just as important. The main tasks of transportation management traditionally are those of scheduling—once more a balance between prompt service and the cost of providing it most economically—and routing, which focuses the classic linear programming problem of achieving the minimum distance (and time) to reach all the delivery points.

In addition, the transportation flow must be coordinated between the different links in the supply chain. Transparency of information flow is crucial here. If the precise transportation status of orders can be tracked at any time, it becomes possible to expedite or reroute shipments to meet emergencies, to consolidate shipments in order to reduce costs, and to minimize the time that shipments simply sit and await further instructions.

It must be remembered that transportation is the by-product of the need to get the product to the customer. Every action that can be taken to reduce movement and handling will improve the process and reduce costs.

The marketer must also make the appropriate selection from the available modes of transportation. This decision is, of course, heavily influenced by the needs of the firm and its customers.

The manager must consider the performance of each mode in three contexts:

(i) Transit time,

(ii) Reliability, and

(iii) Cost.

(i) Transit Time:

The period between departure and arrival of the carrier varies significantly. For example, between ocean freight and airfreight the 45-day transit time of an ocean shipment can be reduced to 24 hours if the firm chooses airfreight. The length of transit time has a major impact on the overall logistic operations of the firm. A short transit time may reduce or even eliminate the need for an overseas depot, and inventories can be significantly reduced if they are replenished frequently.

As a result, capital can be freed up and used to finance other corporate opportunities. Transit time can also play a major role in emergency situations. For example, if the shipper is about to miss an important delivery date because of production delays, a shipment normally made by ocean freight can be made by air.

Perishable products require shorter transit times, and rapid transportation prolongs their shelf life in the market. For products with a short life span, air delivery may be the only way to successfully enter distant markets. For example, international sales of cut flowers have reached their current volume only as a result of airfreight.

(ii) Reliability:

All providers of transportation services wrestle with the issue of reliability. Modes are subject to the vagaries of nature, which may impose delays. Yet because reliability is a relative measure, the delay of one day for airfreight tends to be seen as much more severe and “unreliable” than the same delay for ocean freight. However, delays tend to be shorter in absolute time for air shipments; as a result, arrival time via air is more predictable. This attribute has a major influence on corporate strategy.

For example, because of the higher predictability of airfreight, inventory safety stock can be kept at lower levels. Greater predictability can also serve as a useful sales tool for distributors, who are able to make more precise delivery promises to their customers. If inadequate port facilities exist, airfreight may again be the better alternative. Unloading operations from ocean-going vessels are more cumbersome and time consuming than from planes.

Finally, merchandise shipped via air is likely to suffer less loss and damage from exposure of the cargo to movement. Therefore, once the merchandise arrives, it is ready for immediate delivery—a fact that also enhances reliability.

(iii) Cost:

Transportation services are usually priced on the basis of both cost of the service provided and value of the service to the shipper. Because of the high value of the products shipped by air, airfreight is often priced according to the value of the service. In this instance, of course, price becomes a function of market demand and the monopolistic power of the carrier.

The marketer must decide whether the clearly higher cost of airfreight can be justified. In part, this depends on the cargo’s properties; the physical density and the value of the cargo effects of the decision. Bulky products may be too expensive to ship by air, whereas very compact products may be more amenable to airfreight transportation. High-priced items can absorb transportation cost more easily than low-priced goods because the cost of transportation as a percentage of total product cost is lower.

As a result, sending diamonds by airfreight is easier to justify than sending coal by air. To keep costs down, a shipper can join a shippers’ association, which gives the shipper more leverage in negotiations. Alternatively, a shipper can decide to mix modes of transportation in order to reduce overall cost and time delays. For example, part of the shipment route can move by air, while another portion can move by truck or ship.

Most important, however, are the overall logistic considerations of the firm For example, the marketer must determine how important it is for merchandise to arrive on time. The desire to be at the cutting edge of trends results in the latest clothing fashions always being shipped by air. The need to reduce or increase inventory must be carefully measured. Related to these considerations are the effect of transportation cost on price and the need for product availability.

For example, some firms may wish to use airfreight as a new tool for aggressive market expansion. Airfreight may also be considered a good way to begin operations in new markets without making sizable investments for warehouses and distribution centers.

Although costs are important, the marketing manager must take an overall perspective when deciding on transportation. The manager must factor in all corporate activities that are affected by modal choice and explore the total cost effects of each alternative. The marketer’s choice will depend on the importance of the different transportation dimensions to the market under consideration.

Increasingly, though, organizations are subcontracting their entire transportation operation to outside operators; indeed, this has become the classic make or buy decision. Contract, or third-party, logistics is a rapidly expanding industry. The main thrust behind the idea is that individual firms are experts in their industry and should therefore concentrate only on their operations. Third-party logistics providers, on the other hand, are experts solely in logistics, with the knowledge and means to perform efficient and innovative services for those companies in need. The goal is improved service at equal or lower cost.

Logistics providers’ services vary in scope. For instance, some use their own assets in physical transportation whereas others subcontract out portions of the job. Some providers are not involved with the actual transportation but develop systems and databases or consult on administrative management services. In many instances, the partnership consists of working closely with established transport providers, such as Federal Express or UPS.

These firms happily provide their self- service parcel boxes by the entrances for stores and firms. This way, a customer desiring overnight delivery does not have to expend energy trying to find a carrier willing to perform the service. The concept of improving service, cutting costs, and unloading the daily management onto willing experts is driving the momentum of contract logistics. One of the greatest benefits of contracting out the logistics function is the ability to take advantage of an in-place network complete with resources and experience.

The local expertise and image are crucial when a business is just starting up. The prospect of newly entering a region as confusing as Europe with different regulations, standards, and even languages can be frightening without access to a seasoned and familiar logistics provider.

One of the main arguments leveled against contract logistics is the loss of the firm’s control in the supply chain. Yet contract logistics does not and should not require a firm to hand over control. Rather, it offers concentration on one’s specialization—a division of labor. The control and responsibility to the customer remain with the firm, even though operations may move to a highly trained outside organization.

Decision Area # 3. Facility Decisions:

After deciding what product or service to provide, the organization must decide where to provide it. The questions that follow are how these chosen markets can best be served and how the best possible service can be offered for the lowest cost unfortunately, once again, these two factors are usually in opposition. Service tends to improve with the number of warehouses or branches. At the same time, more warehouses require more buildings, higher inventory, and more staff—in short, higher cost.

The location of any particular central or regional plants can be mapped by calculating the weighted distribution costs for each part of the market to be served. But distribution times and costs are also affected by the pattern of natural barriers, such as rivers and mountains, and by the quality of the road systems. In addition, trade-offs to building warehouses can be found in better modes of transportation and closer collaboration with customers and suppliers, who, for example, may be asked to preposition product for rapid delivery.

This is particularly the case in industrial marketing. For example, when it comes to crucial parts on an assembly line, even an eight-hour delivery delay may be unacceptable because it means shutting down the line. Location models increasingly rely on the use of computer simulations to deal with these considerable complexities.

Decision Area # 4. Inventory Decisions:

Decisions about how much inventory to hold as raw materials, work in progress, or finished goods; where to hold it; and in what quantities are vital. Inventory levels largely determine the level of service that an organization can offer to its customers or clients. The level of inventory is almost totally dependent on the accuracy of the sales forecasts. The vagaries accompanying such forecasts have led to the need for large inventories to be held (as buffers) to maintain customer service levels, and there is usually a clear trade-off between the cost of stockholding and customer service.

Inventory Control:

For most organizations control of inventory is a crucial activity. If a product is not available when the customer wants it, the sale may be lost, and the dissatisfied customer may take the business elsewhere. For example, it has been estimated that under low promotion conditions, retailers lose 6 to 9 percent of sales due to out-of-stock situations. Under conditions of heavy promotion, the losses typically amount to 12 to 15 percent of sales.

For example, in the supermarket industry, stock outs are probably the worst for heavily promoted items on Sunday evenings—just before the restocking takes place. On the other hand, if too much inventory is held, the cost can be exorbitant; in most industries annual inventory holding costs (physical warehousing, financing, administration, shrinkage, and deterioration) can easily exceed 30 percent of the total value of the stock.

Methods of inventory control vary widely in sophistication. One of the simplest methods is to have two “bins” of a product. When the first bin is empty it is replaced by the second (full) one, and another bin of product is ordered. An alternative is computerized inventory control, which in most cases is just a form of stock recording. The record merely states what the balance of stock is—or should be.

More sophisticated versions also make provision for on-order and back-order items. All of these are records of what has happened. The decisions of when and what amount to reorder are the responsibility of the human operator, but the computer helps by providing a reminder when the stock falls below the minimum or reorder point and provides assistance with some of the calculations (such as the EOQ). In service industries it usually also shows the slots available at some time in the future.

One important development in inventory management, pioneered by Toyota, is the just-in-time (JIT) approach. Here components are delivered from the suppliers directly to the production line just as they are needed (or at least only a few hours before). This way, very little stock is held by the manufacturer. It is accordingly a very efficient method of planning inventory.

However, JIT does have hidden disadvantages, the most important of which is its lack of flexibility. It demands flat scheduling, which means that the production runs must be forecast exactly several weeks in advance, because the comparable production runs by the suppliers will take place sometime in advance of the final assembly.

Changes in plan are not possible in the short term; although if the key components are produced in-house and flexible manufacturing (especially reduced setup times) is employed, this disadvantage may be minimized. Equally, the much vaunted inventory savings by the manufacturer may sometimes come about simply because the suppliers are holding buffer stocks instead. Yet the discipline of meeting JIT demands has improved the performance of many organizations.

It should be noted that JIT is not a technique, but the outcome of a very rich package of measures, including zero defects (or total quality management, TQM) and flexible manufacturing, as well as the traditional workforce dedication involving quality circles and multifunctional workers. It is the practical combination of these techniques, along with the support of sophisticated management information systems providing details on production schedules, vendors, parts, buyers, and transportation that offers the greatest reward.

Finally, it needs to be considered that a shift to a just-in-time system makes a company and its production processes much more vulnerable. For example, during the 1996 strike at a brake-pad plant of General Motors, most of the firm’s assembly plants around the nation had to be shut down very quickly due to a lack of product flow and the lack of any inventories. Thus a narrowly focused strike can have major corporate repercussions.

In consequence, a total commitment to just-in-time systems will be particularly successful if management and labor agree not to use this corporate vulnerability as a bargaining chip.

Inventory as a Strategic Tool:

Inventories can be used by the international corporation as a strategic tool in dealing with currency valuation changes or to hedge against inflation. By increasing inventories before an imminent devaluation of a currency instead of holding cash, the corporation may reduce its exposure to devaluation losses. Similarly, in the case of high inflation, large inventories can provide an important inflation hedge.

In such circumstances, the international inventory manager must balance the cost of maintaining high levels of inventories with the benefits accruing from hedging against inflation or devaluation. Many countries, for example, charge a property tax on stored goods. If the increase in tax payments outweighs the hedging benefits to the corporation, it would be unwise to increase inventories before a devaluation.

Decision Area # 5. Communications Decisions:

Logistics management is not concerned only with the flow of materials through the company and its distribution channels. It also deals with the flow of information, including order processing, invoicing, records of each customer’s past usage, forecasts of demand, and stockholding. The logistics system needs to handle the information effectively in order to provide satisfactory customer service at acceptable cost.

It also needs to offer effective communication and information systems so that management can make better day-to-day and long-term decisions. The flow of information has become as important to the success of a company as the flow of physical products. It is information that ensures that the right goods are in the right place at the right time to meet customer needs.

Supply Chain Management – Importance

As competition increases worldwide, an increasing number of firms are frantically combining domestic and international sourcing as a means of achieving a sustainable competitive advantage. Global competitiveness has led to supply chain functions becoming more geographically dispersed and increased the complexity of supply chain linkages. These changes have brought about a need for greater understanding of these linkages.

Managing the supply chain is an effective method to reduce the operational costs and increase customer satisfaction. Today SCM is rapidly becoming a useful method for reducing inventory costs and increasing customer responsiveness in changing market conditions.

In India, companies are linked to their suppliers and retailers through various sources. Application software is being used to do what was done manually earlier. Supply chain systems analyse information from different points on the supply chain. If one supplier fails to deliver, the SCM software helps managers to find another. For example, consider a customer walking into a Wal-Mart store to purchase detergent.

The supply chain begins with the customer and her need for detergent. The next stage of this supply chain is the Wal-Mart retail store that the customer visits. Wal-Mart stocks its shelves using the inventory that may have been supplied from a finished goods warehouse that it manages or from a distributor using trucks supplied by a third party.

The distribution in turn is stocked by the manufacturer such as, P&G. The P&G manufacturing plant receives raw material from a variety of suppliers who may themselves have been supplied by a lower-tier of suppliers.

For example, packaging material may come from Tenneco packaging while Tenneco, in turn, receives raw materials to manufacture the packaging from some other supplier. A supply chain, thus, is a business process that links suppliers, manufacturers, wholesalers, retailers, and customers.

Supply Chain Management – Problems: Distribution Network Configuration, Distribution Strategy, Information, Inventory Management and Supply Chain Execution

Supply chain management must address the following problems:

(i) Distribution network configuration – Number and location of suppliers, production facilities, distribution centres, warehouses and customers.

(ii) Distribution strategy – Centralized versus decentralized, direct shipment, Cross docking, pull or push strategies, third party logistics.

(iii) Information – Integrate systems and processes through the supply chain to share valuable information, including demand signals, forecasts, inventory and transportation etc.

(iv) Inventory management – Quantity and location of inventory including raw materials, work-in-process and finished goods.

(v) Supply chain execution is managing and coordinating the movement of materials, information and funds across the supply chain. The flow is bidirectional.

Supplier Relationship Management:

If you subscribe to the premise that an enterprise value chain is the real deal, you probably realise that the end client is not the only customer that exists. The suppliers are customers as much as the employees and the business partners in your channel. All of them collaborate to make your end client cry tears of joy while they do business with you. As this has evolved over the past two years to the au courant model we are engaged with now, we’ve also seen the interest in and growth of both ERM and SRM — employee relationship management and supplier relationship management.

The former is a construct from Siebel that Siebel swears will be a $20 billion market. ERM is making sure that your employees are fairly compensated for providing quality work. Treat them with respect and make them accountable, reward them for success. Remember that they’re human.

That should do it for ERM. SRM is another story altogether. This is an important component of the customer-centric universe.

Comparing SCM and SRM? C Vs. R?

SCM is the actual processes and practices that govern production and its delivery. SRM governs the relationships between suppliers and the producing company. It resembles CRM strategically, and certainly resembles partner relationship management or channel management down to its practical level. In fact, it is so close in nature to PRM that there is no reason not to include SRM as part of the CRM subset universe.

There is a difference between SCM and SRM besides the middle letter. While SCM supports internal processes to external customers of any variety, SRM supports collaborative networks that are integrating their mutual supply chains.

The components are very different. SRM deals with the human interactions between the suppliers and the company or companies that use them. It uses automation to make the relationships more effective, rather than making the processes more efficient per se. The most advanced SRM solutions, such as People- Soft’s SRM, are 100 percent Internet applications that use portals for supplier (and other) access.

So if you were to dissect the SRM machinery, you’d probably come up with a map that includes sourcing, contract management, procurement, presentment and payment, and perhaps spend analysis. Solutions that are more sophisticated throw in catalogue management, trading partner management, order management, product configurators, ports, and a host of analytics beyond spend analysis that can track supplier performance.

It pays to look briefly at the more common components of an SRM solution. Like any other solution of its ilk, it always should involve planning a strategy for how to execute an SRM initiative (if you are doing it separately). The only notable thought beyond the strategic planning norms outlined in this book is that SRM strategies require thinking about the vendors and suppliers as both customers and partners involved in making the ultimate revenue-producing customer happy. That means they are part of the collaborative chain and have to be happy themselves so the chain that leads to revenue creation doesn’t break.

Here are the major components:

(i) Procurement:

SRM solutions can lead to a number of important benefits in the procurement process. By bringing the processes under control, out- of-control spending is reduced. How often is it that you find some departmental budget monkey going wild and spending on the basis of departmental and not enterprise need, no matter what the damage? This can bring the spending under control and reduce the procurement cycle, increase contract compliance, and reduce the per transaction cost of procurement.

In the more advanced places, catalogue management is improved because of the improvement in the overall procurement processes. Solid workflow routing is introduced so that the orders can be more effectively managed and approvals assigned more quickly. Shipment notices can be issued automatically.

Imagine your weary desire to do some requisitions at 3:00 A.M. because you can’t sleep due to your inability to adjust to the time difference in Nepal. You go online, access a catalogue and the supplier sites that are tied to the items in the catalogue. Built-in business rules govern how the procurement requisition is created. You do all this-in Nepal-at 3:00 A.M. The requisition is created and entered into the system for action. It is secure. You can sleep now. The world is as one.

(ii) Sourcing:

While choosing the right suppliers for a quote or proposal seems to be a matter of both knowledge and the heart, SRM can make this process so much more satisfying and effective. This is not easy. You’ll see that when you see what SRM sourcing modules contain. For example, attribute weighing is a way of defining the important criteria that you set for seeing the value of a prospective bidder or an active one based on algorithms that I can’t begin to comprehend.

Another feature is event scoring and award. These are comparisons of multiple vendors and their responses to a proposal so you can evaluate and choose the winning bidder. Supplier performance is a set of provided or customised metrics that can measure how well a supplier is doing against plan. This can have a real effect on whether you award him a certain piece of business at a certain time. Some of the most commonly used metrics are quality, cost, responsiveness, and delivery speed.

Finally, collaborative negotiations have a direct impact on the deals that are going on with spot buys, reverse auctions, or just plain auctions. Negotiations are real time and have to be done that way. The rapid dissemination of the negotiations information has to be handled through multiple organisational levels for both bidder and buyer SRM sourcing provides the real-time workflow and knowledge management tools to do this.

(iii) Payment:

Who doesn’t know how touchy payment processes are? They are the most sensitive of subjects, the foundation for lawsuits. Those processes when flawed create bad communications and/or late payments and that leads to those lawsuits and highly irrational behaviours between the persons owed and the scofflaw company. All make this a thin-skinned and critical function within SRM.

Paying the suppliers isn’t just the use of your financial applications purchased from an ERP vendor we are talking about managing relationships. If you pay in a timely fashion through an ordinary and comfortably repeatable routine, you don’t have a lot of relationship worries. But what if there are conflicts? How does the settlement process, that which comes between procurement and check to your supplier, get handled? Never fear, SRM is here.

SRM uses workflow to enable alerts that are triggered when payment disputes are initiated. Perhaps it’s a mistake in invoicing or a payment discrepancy. It doesn’t matter If you are using SRM’s best practices, all the invoicing, dispute resolution, and payment issuance are done online via secure portals with unique IDs and passwords for each supplier.

Commonly, the most important analytics for SRM are analytics that help you control costs. For example, there may be a price increase in goods that you regularly order that is not apparent because the ordering process is automatic or automated. You don’t want to see this for the first time after it hits the books.

By doing what is often called spend analytics, you can carve the procurement process into tiny or big or diagonal pieces and see what’s going on with the costs of each part of the procurement. But SRM-related analytics don’t stop there. You can monitor employee spending patterns or analyse purchase data.