Introduction to Effective Communication:

Negotiation is essentially a process of coming to terms with the situation on hand and, in so doing, getting the best deal possible. It involves four steps: Determining objectives of negotiation; preparing for the negotiation; conducting the negotiation, and reviewing the negotiation.

All these four steps are in turn influenced by the situational as well as institutional views as applicable to the issue under negotiation. A manager should essentially get himself acquainted with at least the institutional views under these heads clearly before he goes to the negotiating table.

In any negotiation, each party can ultimately choose only one option from the available alternatives: Accepting the deal or staying put with the best no-deal option, i.e., the course of action it would have taken had there been no ‘deal’.

Despite this hard reality, every negotiator, psychologists say, tends to advance his or her full set of interests. Indeed, he/she would persuade the other party to say ‘yes’ to a proposal that best fits into his scheme of things.

Now the moot question is “why should the other party say yes?” It is often forgotten at the negotiating table that the ‘best’ one party wants to have has to come from the other party who, incidentally, besides controlling it, has different ‘wants’ of his own.

It is thus self-evident that every negotiating executive must not only review his own wants and expectations from the other side but also understand what the other side wants to have from the deal, for in it lies the key for creating and sustaining the ‘value outcome’ from a negotiation.

Negotiation is after all taking something from the other party on which he has the control. Does it therefore not make sense to know what the counterpart’s problem is and how it is viewed by them? The attitude of “let the other side solve its own problem” and we “will look after our own problem”, is bound to impact the outcome adversely.

Yet, as Social Psychologists say, manager-negotiators often find it difficult to understand the other side’s perspective. A shrewd negotiator should therefore cultivate the courage to first address the problem of the counter party for in it lies his own redemption.

Negotiation is thus that simple and yet, as James K Sebenius stated in his 2001 HBR article, even experienced negotiators are often found to make the following six common mistakes, viz.,

i. Neglecting the other side’s problem;

ii. Letting price bulldoze other interests;

iii. Letting positions drive out interests;

iv. Searching too hard for the common ground;

v. Neglecting BATNAs; and

vi. Failing to correct partisan view

That are found to keep the negotiators away from the solution they are seeking to the problem. Experts on negotiation observe that negotiating a deal involves 50% emotion and 50% economics. It is found that the parties to negotiation are not only concerned about economic returns but also care more for other interests such as relative results, perceived fairness, self-image, reputation, etc.

Hence, a shrewd negotiator should care for building up long-term relationships rather than mere immediate economic gains, more so when he has to do business with the same person for years to come. This philosophy makes more sense in handling employee-employer conflicts such as wage settlement, as managers cannot afford to put relationships at risk.

In such negotiations, managers have to go beyond the economic contracts and give more weight to social contracts or put more weight into the “spirit of a deal” in terms of the nature, extent, duration, and the process of relationship and its sustainability.

Elements of Effective Communication:

Issues:

On which agreement is explicitly being pursued;

Positions:

Negotiating party’s stand on the issues under negotiation; and

Interests:

The underlying concerns that would be affected by the outcome of negotiation. It is often found that negotiators have a built-in bias towards their own positions rather than focusing on reconciling the deeper interests. For instance, the management and union while negotiating for a wage settlement must appreciate the underlying interest of the management for maintaining an over all high profit level for the bank.

Once this dawns on the employees, they could easily reconcile their interests for higher wages with those of bank’s interest for higher profit by expanding the very “pie’ via increased output through diligent customer service, more per-employee business, etc., and divide the so increased profit amicably.

Every negotiating party should come to the negotiating table with a “Best Alternative To a Negotiated Agreement” (BATNA) so that they know with what to settle down ultimately, if the proposed deal is not realizable. BATNAs simply set the threshold that any acceptable agreement must exceed. They indeed define a zone of possible agreement and determine its location.

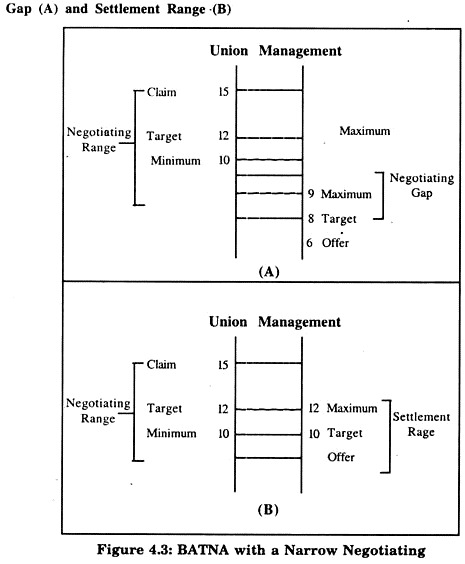

To easily appreciate their effectiveness, let us take the example of negotiation for base increase (Figure 2).

The better a BATNA appears both to the management and the union, the more the management can leverage out of it. For instance, the BATNA under figure ‘A’ has a wide negotiating gap since the maximum rise that the management is willing to give is 9% as against the minimum of 10% rise that union has set as a target.

In view of this the management cannot realize any leverage out of it. On the other hand, the BATNA under ‘B’ affords a wide settlement range and with such BATNA management by threatening to walk out of the negotiating table, they can quickly clinch the negotiation. In other words BATNA of ‘B’ type offers a better opportunity for successful negotiation.

Practice of Effective Negotiation:

Let us examine how these basic tenets of negotiation can be practiced by using a typical and a common compromise proposal emanating from an overdue borrower of a bank. A compromise is a simple mechanism of settling a dispute by the parties involved there under, being willing to grant concessions to each other.

However, the branch should always bear in mind that:

i. Repayment, which it wants, is controlled by the borrower;

ii. Borrower has different wants;

iii. Some approaches work fairly and regularly; and

iv. Forewarned is forearmed, and hence a negotiating manager must skillfully exploit the key elements of the negotiation.

Leverage:

i. The manager should identify as to what the borrower wants to have out of this negotiation and motivate him towards it by drawing borrower’s attention to the benefits/rewards/ punishments he is likely to get, should the negotiation succeed/fail.

ii. The manager should identify the ‘formal power’ that he can use as a negotiator to influence the borrower in the given situation. It could be his own hierarchical status/title or that of a senior from the administrative office by involving him in the negotiation.

iii. The very personality of the manager-negotiator, i.e., his character, his approach to the problem, his orientation towards the customer, his expertise in rightly diagnosing the pros and cons of the issues involved and the choice of words greatly enhances the scope for success.

Information:

i. Knowledge about one’s own position, the position of the other party, the statistics related to both, the common interest of both the parties, the conflict prone areas between the banker and the borrower, the factors that are likely to influence the behavior of the other party, the process through which such information could be elicited and usage of such information for resolving the emerging conflicts greatly influences the outcome.

Timing:

i. Timing of the negotiation has tremendous scope for building up pressure on the borrower to accept a compromise proposition, the rate of success being as high as 80:20.

ii. As the negotiation progresses, the manager should have the knack of readjusting his timing for imparting pressure anew.

iii. Negotiation tends to give results when both the parties are hurt enough and want a way out and the manager should constantly be on the lookout for such ‘weaknesses’ to strike the deal.

Approach:

i. The manager should set himself a high positive goal to harness the self-fulfilling prophecy.

ii. His objectives must be made visible to the borrower.

iii. Open attitude that depicts confidence of mutual success and active listening is likely to enhance the scope for success through healthy dialog.

iv. He should use positive vocabulary and phraseology that sounds encouraging, and yet authoritative and confident which is likely to yield favorable results.

v. Manager’s patience and perseverance should be infinite for they alone can wear out the obstinacy of the other party.

In any dispute, a partisan becomes emotionally involved. He is more likely to get angry. No one in that stage wants to be vindicated, nor wishes to be ‘taken’. Such partisan factors operating consciously or unconsciously at the borrower’s level is likely to distort his judgment. A negotiating banker too is prone to this syndrome.

Secondly, in the organizational context, the negotiator is often forced to avoid taking responsibility under the plea of getting the necessary approval from the higher- ups. Such passing the buck is likely to protract the negotiations besides dampening the spirit of the borrower.

Such prolonged negotiations may result in disillusionment to the borrower and may send wrong signals across the system. It is, therefore, always preferable to get the boundaries for negotiations defined well in advance, of course in consultation with the competent authorities and keep the log positively rolling on, till an acceptable proposition emerges.

Now, the moot question is, what is the acceptable proposition? It is difficult to define, for each loan account is unique by itself. The appropriateness is, therefore, contextual.

Managers have to examine the appropriateness or otherwise of going for a compromise settlement by dispassionately analyzing the customer against the backdrop of:

i. The realizable value of assets charged to the account;

ii. Likely time taken for enforcement of securities through court’s intervention;

iii. Enforceability of securities;

iv. Scope for disposing the assets;

v. Deterioration in the inventory value due to prolonged litigation;

vi. The social status of the borrowers/guarantors;

vii. Their concern for self-esteem;

viii. Whether default is a resultant phenomenon of external or internal factors; and

ix. Whether the borrowers have other sources of income besides the unit financed.

They must undertake such analysis and construct alternatives with economic gains there under well before undertaking the negotiation. As the negotiation progresses, the manager must watch out for any scope to realize the full dues in one stroke with least passage of time for such a possibility helps the bank minimize further loss of earning opportunities.