After reading this article you will learn about:- 1. Introduction to Managing Groups and Group Processes 2. Model of Work Group Effectiveness 3. Types 4. Work Group Characteristics 5. Stages of Group Development 6. Basic Group Characteristics 7. Cost and Benefits Offered by Group 8. Organisational Application 9. Group Cohesiveness 10. Informal Leadership and Other Details.

Contents:

- Introduction to Managing Groups and Group Processes

- Model of Work Group Effectiveness

- Types of Group

- Work Group Characteristics

- Stages of Group Development

- Basic Group Characteristics

- Cost and Benefits Offered by Group

- Organisational Application of Group Concepts

- Group Cohesiveness

- Informal Leadership

- Informal Organisation

- Group Decision-Making

1. Introduction to Managing Groups and Group Processes:

A critical factor affecting the success of an organisation is effective interaction between individuals and groups. If there are misunderstandings or disagreements among members of the organisation the overall efforts of the organisation to achieve its goals partly lose their effectiveness.

The existence of groups in organisations is a simple fact of life. Indeed, an organisation itself could be approached as a group of groups. Therefore, is to establish what a group is and then determine what kinds of groups there are organisations. This will enable us to understand how actual interactions among organisational members enable an organisation to achieve its goals.

Specifically, we focus on only one behavioural process, that is, the context in which most of these interactions occur: group behaviour within one group or between two or more groups. We may well start with the definition of a group.

Definition of a Group:

A group may simply be defined as two or more individuals who interact regularly and influence each other to accomplish a common purpose or goal. Groups can be both large (comprising 100 people) and small (consisting of 2 to 3 people).

Why People Join Groups:

To gain some insight into groups and group processes, we may first examine why people join groups. In truth, people join groups for various reasons. They join functional groups simply by virtue of joining organisations. This means that people accept employment to earn money or to practice their chosen profession.

Once inside the organisation, they are assigned to jobs and roles and thus become members of functional groups. What is normally, though not always, found is that functional group membership precedes task group membership. People in existing functional groups are told, are asked, or volunteer to serve on ad hoc committees, task forces and teams.

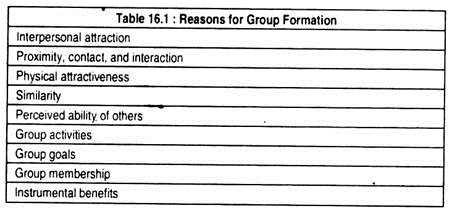

What is of considerably more importance is why people join informal or interest groups. Since organisational people themselves choose or decide whether or not to join such groups, their choices are related to motivation. In this context, Marvin E. Shaw has suggested various reasons, listed in Table 16.1 why people decide to join groups.

1. Interpersonal attraction:

The primary reason why people choose to form informal or interest groups is that they are attracted to each other. There are various reasons for interpersonal attraction such as physical features, similarity of attitudes, personality, economic spending or even the perceived abilities and the usefulness of others. All these factors lead in various degrees to the interpersonal attraction that can result in the formation of an informal or interest group.

2. Group activists:

The second important reason for people to get motivated to join groups is that the activities of the group appeal to them. Jogging, playing cards, gossiping in clubs’ discussing current political motivation are activities that some people enjoy. People enjoy these only when they are in a group and most such activities actually require more than one person.

3. Group goals:

The goals of a group may also be another motivator. They may also motivate people to join. For example, an individual may not like to collect subscription for a political party, but people may join a group to perform the same activity because they subscribe to its goal.

4. Group membership:

Another reason why people join groups is that the mere fact of being a member may be personally satisfying. Industrial psychologists have argued that the need for affiliation prompts people to seek the company of others.

Moreover, the fulfillment of this need seems to reduce their anxiety about being accepted and linked. Others may satisfy their need for esteem by joining groups (such as fraternal organisations) that they admire or feel that other people admire.

5. Infrastructural benefits:

Finally, people join groups because group membership is sometimes seen as instrumental in providing other benefits to the individual. For example, a manager might join a certain tennis club not because he is attracted to its members (although he might be) and not because of the opportunity to play tennis (although he may enjoy it).

The club’s goals are not quite relevant and his affiliation needs may be satisfied in other ways. However, he may feel that being a member of this club will enable him to develop important and useful business contacts. Thus, the tennis club membership is instrumental in establishing those contracts.

2. Model of Work Group Effectiveness:

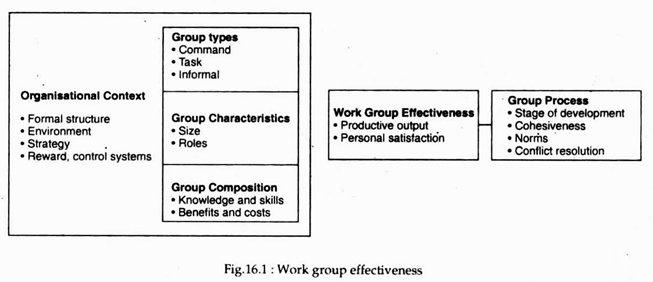

Work group effectiveness depends on a number of factors as shown in Fig.16.1. Group effectiveness basically depends on two things—productive output and personal satisfaction. The former pertains to the quality and quantity of task outputs as defined by group goals. The latter pertains to the group’s ability to meet the personal needs of its members and hence maintain their membership and commitment.

The factors influencing group effectiveness starts with the organisational context. It is a very broad term and encompasses such diverse factors as structure, strategy, environment and control systems. Managers define groups within that context.

Three important group characteristics are:

(i) The type of group,

(ii) The group structure and

(iii) Group composition.

It is of utmost importance to managers to decide when to use a temporary task group. Two other important aspects of group are: its size and its role. It is also necessary for managers to consider whether a group is the best way to do a task. If costs outweigh benefits so that net benefit is positive, managers may seek to assign an individual employee to the task.

It is important to note at the outset that these group characteristics “influence processes internal to the group, which in turn affect output and satisfaction. Group leaders must understand and manage stages of development, cohesiveness, norms and conflicts in order to establish an effective team. These processes are influenced by group and organisational characteristics and by the ability of group members and leaders to direct these processes in a positive manner.”

3. Types of Group:

There are various groups in an organisation. The best way to classify groups is in terms of those created as part of the organisation’s formal structure and those that arise informally within the organisation.

a. Formal Groups:

A formal group is one which is created by the organisation to perform a specific task.

Formal groups are of the following two broad categories:

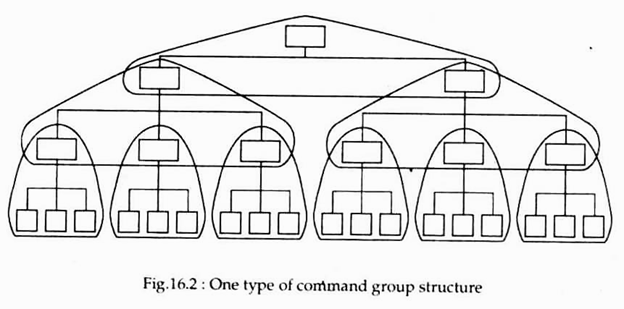

(i) Command Group:

It is composed of a manager and his (her) subordinates in the organisation’s formal chain of command. It is also called a functional group because it normally represents a specific department or work unit in the organisation. A functional group is group created by the organisation to accomplish a number of organisational purposes with an indefinite time horizon.

The accounting department, the personnel department or the quality control department or the production department of a manufacturing firm are examples of functional groups. Such a group is created by the organisation to reach specific goals through members’ joint activities and interactions.

Other examples of such groups are operating work groups, autonomous work groups, and standing committees, as also the marketing department and the human resource department. Each is created by the organisation to serve a number of purposes specified by the organisation.

For example, the production department in a manufacturing firm seeks to produce large number of products while allowing minimal waste and using human resources as effectively as possible. It is assumed that the functional group will remain in existence after it attains its current objectives.

Fig. 16.2 illustrates one type of functional group structure. It is observed that middle-level managers are a part of two command groups and hence serve as what Likert calls ‘linking pins’ between them. The functional structure defines a series of groups that serve as building blocks to create the organisation in its totality.

(ii) Task Group:

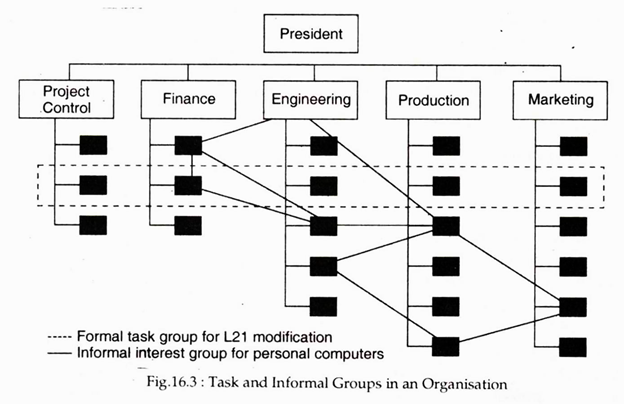

A task group is created to achieve a specific goal or a narrow range of purposes within a limited time period. Such a group does not reflect the organisation’s command or functional structure. Members of such groups may be drawn from several departments, given a specific task and disbanded after completing the task. Task groups also go by the names teams, task forces, project groups and committees.

The organisation specifies group membership and assigns a relatively narrow set of goals, such as developing a new product or evaluating a proposed grievance procedure. The time horizon for accomplishing these purposes is either specified or implied (the project team quits when the new product is developed).

b. Informal Groups:

Such groups are created by employees themselves (and not by the organisation) and are so designed as to meet their mutual interests.

They may be created on the basis of friendship or shared interests and thus are of the following two categories:

(i) Interest Group:

Interest group is formed on the basis of a common personal interest among members. It is created by its members for purpose that may or may not be relevant to those of the organisation and it has an unspecified time horizon. An example of this is a group set up to work on an invention that the company has authorised.

The members of these always choose to participate — rather being told to do so. An informal group is spontaneous with no continued existence; an interest group continues over time and the activities of the group may or may not match the goal of the organisation.

(ii) Friendship Group:

It is based on members’ enjoyment of personal interactions with one another and involves for ensuing social interaction such as shopping or lunching.

Fig.16.3 illustrates the important point that informal groups can include any employees in the organisation. It shows how formal task forces and informal groups both cut across the vertical command structure. It is interesting as also instructive to note that formal groups often have members at the same organisational level, but informal groups can have members from any level or department. And informal groups can be a powerful organisational force with which managers must contend.

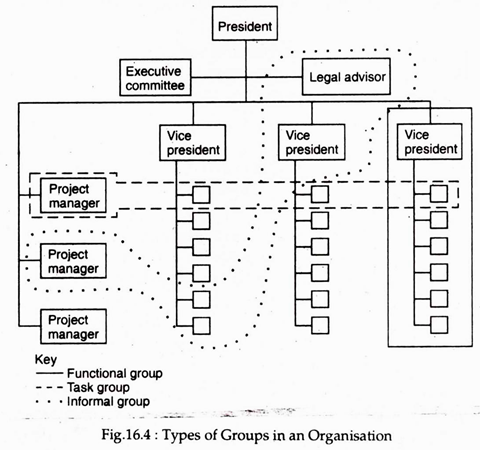

Fig. 16.4 reflects the pervasiveness of groups in organisations. The people inside the box covered by a solid line (as well as the other departments and the executive committee) make up a functional group. The people inside the box shown by a broken line constitute a task group within a matrix structure.

Finally, the area indicated by a broken line and dots represents an informal group composed of the legal adviser, a vice-president, a project manager, and two subordinates.

These people may meet in clubs or weekends, or play golf together, or simply chat around at lunch time. Various other types of informal groups may also exist.

4. Work Group Characteristics:

Two important characteristics of groups are of considerable importance to internal processes in organisations as also group performance. These are: group size and member roles.

Size:

The ideal size of a group varies between 7 and 12 and is consistent with satisfactory group performance. In one sense such groups are large inasmuch as they can take advantages of diverse skills, enable members to express good and bad feelings and aggressively solve problems. In another sense, they are small enough to permit members to feel that they are an intimate part of the group to serve everyone’s needs.

Research on group size suggests that, as a general rule, as group size increases it becomes increasingly difficult for each member to interact with and influence the others. This explains why large groups make need satisfaction for individuals more, difficult; thus, there is less reason for people to remain within the group or be committed to its goals.

Member Roles:

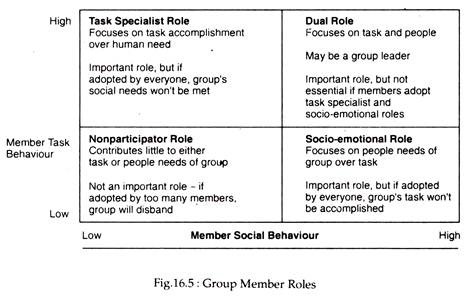

Members play various group roles. The most important such role is task specialist role, a role in which the individual devotes personal time and energy to help the group accomplish its task.

People who play such role spend time and energy helping the group reach its goal, by displaying the following behaviours:

(a) Initiation:

Propose new solutions to group problems.

(b) Giving opinions:

Offer opinions on task solutions; give frank and open feedback on others’ suggestions.

(c) Seeking information:

Ask for task-relevant facts.

(d) Summarising:

Relate various ideas to the problem at hand; pool ideas together into a summary perspective.

(e) Energising:

Stimulate the group into action when interest drops.

Another role played by members in a group is socio-emotional role, a role in which the individual provides support for group members’ emotional needs and social unity.

In playing this role members display the following behaviours:

(a) Encourage:

They are warm and receptive to others’ ideas; praise and encourage others to draw forth their contributions.

(b) Harmonise:

They reconcile group conflicts; help disagreeing parties reach agreement.

(c) Reduce tension:

They may tell jokes or in other ways draw off emotions when group atmosphere is tense.

(d) Follow:

They go along with the group; agree to other group members’ ideas.

(e) Compromise:

They will shift own opinions to maintain group harmony.

In order for a group to be successful over the long run, it must be structured so as to both maintain its members’ social well- being and accomplish the group’s task. Members must actively fill both task specialist and socio-emotional orders to ensure the group’s long term success. Fig.16.5 illustrates these two roles.

Fig.16.5 also shows that some members may play a dual role, a role in which the individual both contributes to the group’s tasks and supports the emotional needs of members.

Finally, members play non-participator role, a role in which the individual contributes little to either the task or members’ socio-emotional needs.

In this context Dafts has suggested that “effective groups must have people in both roles. Humour and social concern are as important to group effectiveness as are facts and problem solving.”

A related point has also been underscored by Drafts:

“Managers also should remember that some people perform better in one type of role; some are inclined toward social concerns and others toward task concerns. A well-balanced group will do best over the long term because it will be personally satisfying for group members and permit the accomplishment of group tasks.”

5. Stages of Group Development:

Groups tend to evolve over a fairly long period of time and are dynamic in that they probably never achieve a completely stable structure; the organisation is always changing, however slowly, as are the relations among the members of a group.

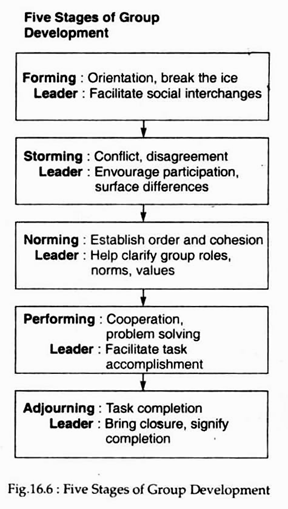

Research suggests that group development evolves over five clear stages, as illustrated in Fig. 16.6.

The five stages typically occur in sequence:

1. Forming (testing and dependence):

The first stage of group development is a period of testing and dependence, or forming. In this stage group members learn about each other and orient themselves to the situation.

In other words, the members of the group get acquainted and begin to test which interpersonal behaviours are acceptable and which are not acceptable to the other members of the group. The members are very dependent on others at this stage to provide clues about what is acceptable. The basic group rules for the group are established and a tentative group structure may emerge.

2. Storming (intra-group conflict and hostility):

Intra-group conflict and hostility, or storming, is the second stage of group development. During this stage individual personalities emerge and group members begin to engage in conflict and disagreement with one another, often over what the group is supposed to be doing.

New members of the group resist the structure that has begun to emerge. Each member wants to retain his individuality. There may be a general lack of unity, and patterns of interaction are uneven. At the same time, some members of the group may start exerting themselves so as to become recognized as the group leader, or at least to play a major role in shaping the group’s agenda.

3. Norming (development of group cohesion):

The third stage is the development of group cohesion, or norming. During this stage there is conflict resolution and emergence of group harmony and unity. The group agrees on certain norms or rules governing behaviour in the group.

During this stage each person begins to recognise and accept his role and to understand the roles of others. Members also start accepting one another and to develop a sense of unity. But, there may be temporary disturbances in the storming stage. For example, the norming group might begin to accept one particular member as the leader.

If this person later violated important norms and otherwise jeopardised his claim to leadership, conflict (storming) might re-emerge as the group rejected this leader and searched for another.

4. Performing (Functional role-relations):

Performing is the next stage of group development, wherein the group really begins to falls on the problem at hand. The group finally settles down to complete its assigned tasks during this stage. Members become committed to the group’s mission. Roles usually become more flexible in that group members are willing to take on responsibilities not specifically assigned to them to complete the work.

The members enact the roles they have accepted, interaction occurs, and the efforts of the group are directed towards goal attainment. The basic structure of the group is no longer an issue but has become a mechanism for accomplishing the purposes of the group. Thus, the group structure is now very supportive to task performance.

5. Adjusting:

It refers to the final stage of group development. This stage occurs in committees, task forces and teams that have a limited task to perform and are disbanded afterward. During this final stage, the stress is on wrapping up and gearing down associated with task completion.

Conclusion:

The above five steps do not occur as discrete steps with measurable starting and stopping points. However, they do reflect basic processes through which groups normally pass. Various models of group development have been proposed but the one outlined above gives a very clear picture of how a fully functioning group evolves from a loose collection of individuals.

6. Basic Group Characteristics:

As groups develop they begin to take on important characteristics.

Three such characteristics, are the following:

1. Role Dynamics:

Different people in an organisation play different roles and the same individual may even play more than one role. While some people assume the role of leaders, others do the work. Some others even interface with other groups, and so on.

Furthermore, each individual is not only a part of an organisation but a part of the broader society. This means that each belongs to many groups and, therefore, plays multiple roles — in work groups, classes, families and social organisations.

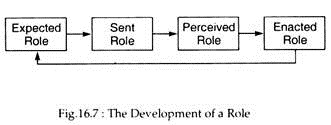

The term role dynamics is used because the different roles are to be played by a group with the passage of time. As described in Fig. 16.7, the process starts with the expected role which indicates what other members of the group expect the individual to do.

The expected role then gets translated into the sent role, which group members use to communicate the expected role to the individual. The perceived role is what the individual perceives the sent role to mean. Finally, the expected role is what the individual actually does in the role. And, the enacted role, in turn, influences future expectations of the group.

2. Role Ambiguity:

Role ambiguity arises when the sent role is under. In work settings, role ambiguity arises for various reasons such as poor job descriptions, vague instructions from a supervisor, or unclear cues from co-workers and colleagues. For any or all of these reasons the role of the subordinate becomes ambiguous.

He does not know what to do. It is quite obvious that role ambiguity can cause a significant problem for both the individual who must content with it and the organisation that expects the employee to perform.

3. Role Conflict:

This occurs when the manager and cues comprising the sent role are clear but contradictory or mutually exclusive.

Various types of role conflict can occur:

First, we find inter-role conflict, wherein a conflict arises between roles. In a matrix organisation, such conflict often arises between the role one plays in different task groups as well as between task group roles and one’s permanent role in a functional group.

Another form of role conflict is intra-role conflict. In this situation, the person gets conflicting demands from different sources within the context of the same role. When the cues are in conflict, the manager may be unsure about which course to follow.

Intrasender conflict occurs when a single source sends clear but contradictory messages.

Finally, personal role conflict results from a discrepancy between the role requirements and the individuals’ personal values, attitudes and needs.

Role conflict is of particular concern to managers. Conflict may also occur in various types of situations and lead to a variety of adverse consequents, including stress, poor performance and rapid turnover.

Role Overload:

A final consequence of poor role development is role overload, which occurs when expectations for the role exceed the individual’s capabilities. The employee often experiences load overload when a manager gives him (her) several major assignments at once while increasing the person’s regular workload. Role overload can be avoided simply by recognising the individual’s capabilities and limits.

Group Norms:

The second important characteristic of groups is their norms, which are simply standards of behaviour that the group accepts for its members. Most committees, for example, develop norms governing their discussions.

Norms define the boundaries between acceptable and unacceptable behaviour. Some groups develop norms that limit the upper bands of behaviour to “make life easier” for the group. As a general rule, these norms are counterproductive. Other groups may develop norms that limit the lower bounds of behaviour. These norms tend to reflect motivation, commitment and high performance.

Normal Generalisation. The important point to note here is that the norms of one group cannot be generalised to another group. People who are unable to observe this norm are ‘punished’ by sarcastic remarks or even formal reprimands.

In this context, Griffin has pointed out that, “even within the same work area, similar groups can develop different norms. One work group may strive always to produce above its assigned quota; another may maintain productivity just below its quota. The norm of the group may be to be friendly and cordial to its supervisor; that of another group may be to remain aloof and distant. Such differences are due primarily to the composition of the groups.”

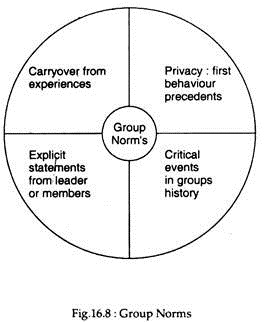

A norm is a rule — a standard of conduct which is shared by group members and guides their behaviour. There are four sources of group norms illustrated in Fig.16.8, which is self-explanatory.

Managing Conflict:

The final characteristic of group process is conflict. Whenever people work together there is scope for conflict.

This can be resolved by:

(1) Setting super-ordinate goal (or goal that cannot be reached by a single individual) and well-defined tasks in highly performing groups and

(2) Mediation (which refers to the process of using a third party to settle a dispute.)

The group finally settles down to complete its assigned tasks during this stage. Members become committed to the group’s mission. Roles usually become more flexible in that group members are willing to take on responsibilities not specifically assigned to them to complete the work.

The members enact the roles they have accepted, interaction occurs and the efforts of the group are directed toward goal attainment. The basic structure of the group is no longer an issue but has become a mechanism for accomplishing the purposes of the group.

Thus, the group structure is now very supportive to task performance.

7. Cost and Benefits Offered by Group:

The best benefits offered by group is social facilitation — the tendency for the presence of others to influence an individual’s motivation and influence. Social facilitation has its greatest positive effect on physical and routine tasks that require less concentration.

However, there are three potential costs of groups:

a. Free rider:

A person who benefits from group membership but does not make a proportionate contribution to the work of the group.

b. Co-ordination costs:

The time and energy needed to co-ordinate the activities of a group to enable it to perform its tasks are’ often on the high side.

c. Diffusion of responsibility:

There is lack of individual responsibility for group outcomes.

8. Organisational Application of Group Concepts:

Group concepts find application in many organisations through decisions to perform more activities through groups. These organisations establish task forces, committees and other work groups as the best way to accomplish organisational tasks.

Norm Variation:

Norms often dictate role dynamics in the sense that the norms prescribe different roles for different group members. A common norm is that the least senior member of a group is expected to perform unpleasant or trivial tasks for the rest of the group. These tasks might be to deal with complaining customers (in a textile showroom) or handle the low commission line of merchandise (in a sales department).

Other examples of norm variation may be cited. For instance, certain individuals, especially informal leaders, may violate the norms with impunity in certain situations. People with expert power may also be allowed to violate norms.

Norms conformity:

Norms have the power to force a certain degree of conformity among group members.

The following four sets of factors contribute to norm conformity:

1. Factors associated with the group itself affect conformity. For example, some groups are likely to create more pressure for conformity than others.

2. The initial stimulus that prompts behaviour can affect conformity. The more ambiguous the stimulus (for instance, the news that the group is going to be transferred to a newly created unit), the more pressure there is to conform.

3. Individual traits, such as intelligence determine the individual’s propensity (tendency) to conform. For example, more intelligent people are often less susceptible to pressure to conform.

4. Finally, situational factors such as group size and unanimity are likely to influence conformity.

Implications:

When a person fails to conform, various things may happen. At first, the group may increase its communication with the deviant individual to try to bring him(her) back in line. If this technique does not work, communication may decline. With the passage of time, the group may begin to exclude the individual from its activities and, in effect, ostracize the person.

If the norm is very powerful and fraught with emotional overtones, physical coercion may even be used. Thus, people who cross union picket lines are at times subjected to physical abuse.

9. Group Cohesiveness:

A third important group characteristics is group cohesiveness, which indicates the extent to which managers are attracted to each other as also to the group as a whole.

Another important and critical aspect of the group process is cohesiveness. It can be defined as the extent to which group members are attached to one another to feel close to one another and motivated to remain in it. Studies point out that “members of highly cohesive group are committed to group activities, attend meetings and are happy when the group succeeds. Members of less cohesive groups are less concerned about group’s welfare and success. High cohesiveness is normally considered as an attractive feature of groups.”

There are various determinants and consequences of group cohesiveness. One research work has pointed out that “frequent group interaction and shared goals increased group cohesiveness. Steelcase (USA) encourages full exchange of ideas among group members at all organisational levels. Employees participate in discussions and programmes on improving productivity, profitability and product quality. Because of the groups’ good relationship with management, their cohesiveness is associated with excellent performance.”

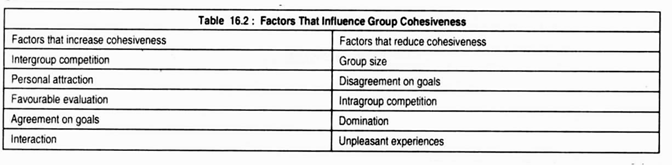

What is of particular importance to practising managers are- (1) the factors that increase and/or reduce cohesiveness and (3) the consequences of group cohesiveness. The factors that influence cohesiveness are enumerated in Table 16.2.

Factors that Increase Cohesiveness:

Five factors are likely to increase the level of cohesiveness in a group. The first, and perhaps the strongest one, is intergroup competition. When two or more groups are in direct competition (for example, three sales groups competing for top sales honours), each group is likely to become more cohesive.

The second is personal attraction which not only helps group formation but increases group cohesiveness. Thirdly, favourable evaluation of the entire group by outsiders can increase cohesiveness. Thus, a group’s winning a sales contest or receiving recognition and praise from a superior will tend to increase its cohesiveness.

In a like manner, if all the members of the group come to reach an agreement on their goals, cohesiveness is likely to increase. Furthermore, the more frequently members of the group interact with each other, the more likely the group is to become cohesive.

As Griffin has put it:

“A manager who wants to foster a high level of cohesiveness in a group might do well to establish some form of intergroup competition, assign members to the group who are likely to be attracted to one another, provide opportunities for success, establish goals that all members are likely to accept and allow ample opportunity for interaction”.

Factors that Reduce Cohesiveness:

There are five factors which are likely to reduce group cohesiveness. The first factor is size. Since size is an important element in groups once size reaches a certain point (perhaps around 20 members), subgroups tend to emerge. In a like manner, as group size increases beyond a certain point cohesiveness tends to decline.

Disagreement:

Secondly, if there is disagreement among the members of a group on what the goals of the group should be, cohesiveness may decrease. For instance, when some members believe that the group should maximise output and others think output should be curtailed, cohesiveness declines.

Intergroup competition:

Thirdly, cohesiveness is likely to be reduced due to intra-group competition. In fact, when members are competing among themselves they focus more on their own actions and behaviours than on those of the group.

Personal domination:

Fourthly, one or two persons dominate in the group — overall cohesiveness is likely to decline. Other members may feel that they are not being given an opportunity to interact and contribute. Consequently they are likely to become less attracted to the group.

Unpleasant experiences:

Finally, unpleasant experiences that result from group membership are likely to reduce cohesiveness. For example, a sales group that stands last in a sales contest, or a group reprimanded for poor-quality work may become less cohesive as a result of their unpleasant experience.

Consequences of Cohesiveness:

On the basis of his own empirical research, Marvin E. Shaw has discovered that, as a general rule, as groups become more cohesive their members tend to interact more frequently, conform more to group norms and become more satisfied with the group.

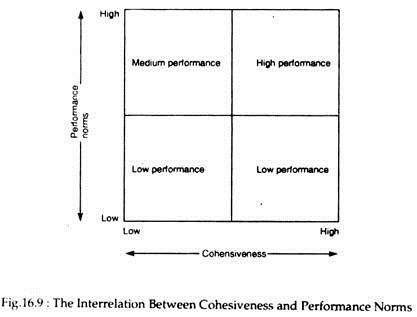

Moreover, cohesiveness is likely to influence group performance. However, performance is also influenced by the performance norms of the group. To be more specific, when a group seeks to maintain high levels of performance, its performance norms are high; when it wants to do just enough to avoid penalties, its performance norms are low. Fig.16.9 shows the manner in which a group’s level of cohesiveness and its performance norms interact.

When both cohesiveness and performance norms are high, high performance should result. This is because the group wants to perform at a high level (norms) and its members are committed to working together toward the end (cohesiveness). When performance norms are and cohesiveness is low, performance is likely to be moderate.

Although the group wants to perform at a high level, its members are not necessarily working together as a unit. When performance norms are low, performance will also be low, regardless of whether group cohesiveness is high or low.

10. Informal Leadership:

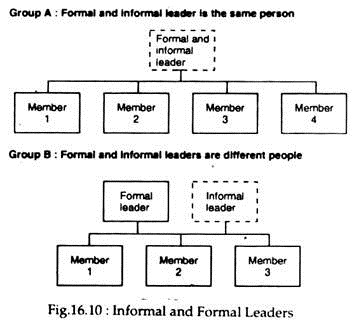

Most functional and task groups have a formal leader which is appointed by the organisation itself or chosen by the group itself. By contrast, an informal leader is one who engages in leadership activities but whose right to do so has not been fully recognised.

In fact, the formal and the informal leader in any group may be the same person, or they may be two different persons. Fig. 16.10 shows these two possibilities in five-person groups. Group X has one person filling both positions whereas. Group Y has both a formal leader and an informal one.

The two common roles relate to that of task specialist, who concentrates on getting the job done, and that of maintenance specialist, who concentrates on bolstering morale and building cohesiveness. The truth is that most groups require both functions even though it is difficult, in reality, for the same individual to fill both roles successfully.

If the former leader can do both, an informal leader is unlikely to emerge. If the formal leader can fulfill one role but not the other, an informal leader often emerges to supplement the formal leader’s functions. If the formal leader cannot fill either role, one or more informal leaders are likely to emerge to carry out both sets of functions.

The pertinent question here: Is informal leadership desirable? There is no denying the fact that in many cases informal leaders are quite powerful because they draw from referent or expert power. When they are working in the best interests of the organisation, they can be a tremendous asset.

11. Informal Organisation:

What is of even more importance than informal leadership is the informal organisation. In all organisations of more than a few individuals, a shadow organisation underlies the formal organisation structure. Managers who hope to deal successfully with groups should be aware of the many facets of informal organisations.

Recall that the informal organisation can be defined as the patterns of influence and behaviour arising from friendship and interest groups in organisations. No doubt, the informal organisation may follow the lines of the formal organisation structure. But, it is more likely to deviate from it.

Informal organisations develop in understandable ways. People who work together in the same physical area, even though they may be part of different formal organisation units, may become part of informal organisations. People who share the same attitudes may “find” those who must communicate frequently with one another also may become part of informal organisations.

These informal organisations may be separate from one another or they may be parts of one large informal organisation. Clearly, it is necessary for managers to analyse and understand such organisations.

Reasons for the Informal Organization:

1. Communication:

Prima facie, access to the informal communication network, or grapevine, is one reason why people join the informal organisation. Information passes very rapidly (though not always very accurately) through this network. Thus, people who are “plugged in” feel they get inside information on time.

2. Social satisfaction:

Interacting with others and being accepted in an informal group often provide social satisfaction to people in organisation. They know they are being accepted for reasons above and beyond and their formal organisational role. Moreover, they derive psychic satisfaction from belonging to the informal organisation.

3. Balance and security:

Finally, people participate in the informal organisation because it offers balance in the sense that it may serve to counter tedious and routine job by providing social interaction and security in the sense that an individual may derive comfort from knowing that he (she) is supported and backed up by others in the informal organisation.

Advantages and Disadvantages of the Informal Organization:

The informal organisation has several advantages and disadvantages. On the positive side, the informal organisation may provide social satisfaction for employees that is missing in their formal jobs, reinforce high performance norms, supplement the formal activity system by providing dedicated informal leaders, or increase group cohesiveness.

On the negative side, or in other situations, the informal organisation may reinforce low performance norms, transmit damaging or inaccurate information, unite one set of employees against another, or undermine the formal authority system through the presence of informal leaders.

The nub of the matter is that the manager must not ignore or try to eliminate the informal organisation. It is important to recognise the informal organisation and respect it for the power it has to achieve positive as well as negative results. The truly effective manager is one who manages both the formal organisation and the informal one.

12. Group Decision-Making:

In most progressive organisations today, important decisions are made by groups rather the individuals. Examples range from executive committees to design teams to marketing planning groups. All types of organisations — business and non-business — rely on group decision-making. And, in most cases, decisions are reached through some sort of consensus process rather than through the voting system.

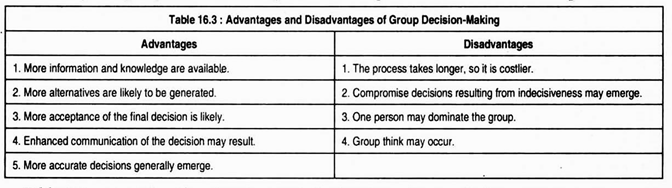

In this context, it will be of interest to discuss the advantages and disadvantages of group decision-making as also techniques for such decision making.

Table 16.3 summarises the advantage and disadvantage of group decision-making:

Advantages of Group Decision-Making:

1. Availability of information:

Perhaps the most important advantage of group decision-making over individual decision making is that there is much more information available in a group setting. Since two brains are usually if not always better than one when a group is assembled, a variety of education, experience and perspective is represented.

If one manager is very familiar with television and video and another is an export on personal selling, their combined knowledge and experience in deriving an overall advertising campaign is substantially greater than that possessed by either working alone. Largely due to the availability of this increased information, groups can usually identify and evaluate more alternatives than one individual can.

2. Greater commitment:

Secondly, as Griffin has argued, “People who are involved in making a decision are more likely to be genuinely committed to the final alternative selected than if someone else had made the decision and imposed it on them. The people involved in a group decision understand the logic and rationale behind it and are better equipped to communicate the decision to their work groups or departments”.

3. Better decisions:

Finally, groups are normally found to make better decisions than individuals. This point has been proved by empirical results.

Disadvantages of Group Decision-Making:

However, group decision making is not an unmixed blessing.

There are a few major disadvantages of group decision-making such as the following:

1. Delay:

Perhaps the most serious drawback of group decision making, compared with individual decision making, is the additional time and (hence) the greater expense entailed. Largely, due to interaction and discussion among group members group decision making is both a time-consuming and cost-raising process.

If group decision is somewhat better than individual decision, then the additional expense may be justified, but group decision making is more costly and should be used only when the results are likely to justify the expense in cost-benefit terms.

2. Undesirable compromises:

The second disadvantage of group decision making is that group decisions often represent undesirable compromises. For example, hiring a compromise top manager may be a bad decision in the long run because he may not be competent enough to respond adequately to any of the various special subunits in the organisation.

3. Dominance:

The third disadvantage of group decision making is that at times one individual dominates the group process to the point where others cannot make a full contribution. This dominance is the result of a desire for power or a naturally dominant personality. The basic problem here is that what appears to emerge as a group decision may actually be the decision of one person.

4. Groupthink:

Finally, a group may succumb to a problem, called group think, which occurs when the group’s desire for consensus and cohesiveness overwhelms its desire to reach the best possible decisions.

As Griffin has put it: “Under the insidious influence of groupthink, the group may arrive at decisions that are not in the best interest of either the group or the organisation, but rather avoid conflict among group members.”

How to avoid the problem? Irvin L. James, who developed the concept in 1982, suggested that a group can do a few things to avoid groupthink. First, each member of the group should critically evaluate all alternatives. Secondly, the leader should not make his(her) own position known too early so that divergent viewpoints can be presented. Thirdly, at least one member of the group should be assigned the role of devil’s advocate.

Finally, after reaching a preliminary decision, the group should hold a follow-up meeting wherein divergent viewpoints can be raised again, if any group members wish to do so.

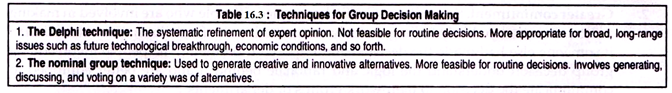

Techniques for Group Decision Making:

Various techniques have been developed to manage or structure the group decision making process. Two most widely used techniques are the Delphi technique and the nominal group technique. These are summarised in Table 16.3.

1. The Delphi Technique:

It is essentially a method for developing a consensus of expert opinion. The technique developed by the Rand Corporation. It solicits input front a panel of experts who contribute individually. Their optimums are pooled and, in effect, averaged.

However, this method has much less appeal to practising managers than it apparently seems. In truth, the time, expense and logistics of the Delphi technique rule out its use for routine, everyday decisions. Yet, it has been successfully used for forecasting technological breakthroughs, market potential for new products, research and development patterns and future economic conditions.

2. Nominal Group Technique:

The second method for managing group decision making is the nominal group technique, or NGT. Unlike the Delphi method, wherein the members of a group do not see each other, or interact with one another, group members in an NGT session are in the same room. However, the members represent a group in name only; they do not interact in a fashion typical of most groups.

The basic point to note is that nominal groups are used most often to generate creative and innovative alternatives or ideas. The highest-ranking alternative represents the decision of the group. However, the manager in charge may retain the authority to accept or reject the group decision.

Advantage:

The most important advantage to be secured from NGT is that it identifies a large number of alternatives while minimising individual inhibitions about expressing unusual ideas.

Disadvantage:

The main disadvantage of this technique is that if the manager ultimately rejects the group decision, enthusiasm for participating in the future is likely to be dampened.

Conclusion:

On balance, it appears that the NGT is a valuable tool for group decision making. It is likely to be used by more and more groups in future.

Managing Groups in Organisations:

A flow guideline for managing groups and group processes in organisations may be suggested.

Managing Task Groups:

The following basic guidelines may be suggested for designing task groups or teams for use especially in a matrix design.

These guidelines are as follows:

(1) Most of the group members should be line managers who will be ultimately responsible for implementing the group’s output.

(2) The group should have required access to all relevant information.

(3) Group members should have the power to command their departments to follow various courses of activities.

(4) The influence system in the group should be based on expert power.

(5) The task group should be integrated with relevant functional departments.

(6) Group members should be chosen for both their technical expertise and their interpersonal skills.

Managing Autonomous Work Groups:

The following five suggestions may be put forward for managing autonomous work groups:

(1) The group should probably have no more than fifteen members.

(2) Certain forms of organisation development should be avoided.

(3) The reward system should reward the entire group as opposed to individuals.

(4) The group supervisor should serve more as coordinator and liaison than as decision maker.

(5) The group should have the authority to plan, organise and control its work.

Managing Committees:

Several guidelines for managing committees have also been suggested. According to H. Koontz and C.O’Donnell, it is of paramount importance to clearly define the goals of the committee, specify the committee’s authority, start and stop meetings schedule, maintain an agenda, appoint a formal leader and hold the number of members to ten or fewer.

Other Guidelines:

In addition to those specific guidelines, some general guidelines have been suggested for managing various types of groups.

Four general guidelines are relevant in this context:

1. Clear definition of roles:

Firstly, the group should be designed in such a way as to minimise the potential for difficulties in role dynamics. Roles must be carefully defined unless there is a clear reason to the contrary (for example, one guidelines for autonomous work groups is to allow workers to create their own roles).

2. Setting high performance norms:

Secondly, the group should be so designed as to faster high performance norms. For example, there is need to reward high group performance or assign highly productive individuals to the group.

3. Enhancing group cohesiveness:

Thirdly, there is need to facilitate and enhance group cohesiveness. This can be accomplished by encouraging interaction and avoiding intra-group competition.

4. Understanding the role of informal leaders:

Finally, it is absolutely essential to identify the informal leaders and to understand their role.

As Griffin has put it:

“An informal leader who does a good job in the maintenance role might be assigned to a group with a formal leader who is more concerned with the task role. Of course, the members of the informal organisation must also be accounted for”.