After reading this article you will learn about:- 1. Basic Concept and Definition of Organisation 2. Importance of the Organising Process 3. Organisation Design Process 4. Internal Contingency Factors: Technology 5. External Contingency Factor: Environment and Information Processing 6. Environment.

Contents:

- Basic Concept and Definition of Organisation

- Importance of the Organising Process

- Organisation Design Process

- Internal Contingency Factors: Technology

- External Contingency Factor: Environment and Information Processing

1. Basic Concept and Definition of Organisation:

There is need for an organisation whenever groups of people work together to reach common goals. Thus, in essence, organisation is a group of individuals with a common goal, bound together by a set of authority-responsibility relationships. One of the functions of management is to co-ordinate available resources of an organisation for effective operations.

Thus organising is the management function that establishes relationships between activity and authority.

It refers to the following four distinct activities:

1. It determines work activities that are to be done to achieve organisational goals.

2. It classifies the type of work needed in various categories and then groups the work into several managerial work units.

3. It assigns the works to individuals and delegates the appropriate authority.

4. It designs a hierarchy of decision-making roles and relationships. An organisation is the end result of the organising process. Thus an organisation is a whole consisting of unified parts (a system) acting in harmony to execute tasks to achieve goals both effectively and efficiently.

The term ‘organising’ is interpreted in four different ways. It may refer to any or all of the following:

1. The way management designs a formal structure to most effectively use the financial, physical, material and human resources of the organisation.

2. How the organisation groups its work into activities, with each group being placed under a manager having the authority to supervise group members.

3. Establishing proper relationships among functions, jobs, tasks and employees.

4. The way managers subdivide the tasks to be accomplished in their respective departments and delegate the necessary authority to perform the tasks.

‘Organisation’ is a broad term.

Therefore a study of the organising process is based on a number of important concepts such as:

(1) division of labour, or specialization,

(2) use of formal organisation charts,

(3) chain of command,

(4) unity of command,

(5) communication channels,

(6) departmentation,

(7) levels of hierarchy,

(8) span of management,

(9) use of committees,

(10) bureaucracy, and

(11) the inevitability of informal groupings.

Above all, there is an important organising process know as the exercise of organisational authority. Before we develop these concepts it is necessary to make a brief review of the relationship between planning and organising, importance of the organising process and the nature of the organising process.

2. Importance of the Organising Process:

The successful completion of the organising process enables management to attain the purpose of the organisation. Moreover, managers are also concerned with the subsequent development, or modification, of an organisation structure.

The organising process is supposed to provide the following real benefits:

a. A Co-Ordinated Work Environment:

In a modern organisation every member must know what to do. So it is necessary to clarify at the outset the tasks and responsibilities of all individuals, departments and major organisational divisions. The time and limits of authority are to be determined. All these are made possible by the organising process.

b. A Co-Ordinated Environment:

The organising process has to be carried out properly to minimize confusion and remove obstacle to performance. For this prior development of interrelationship of various work units is necessary. It is also necessary to define and specify the guidelines for interaction among personnel.

Moreover, it is of utmost importance to achieve the principle of unity of direction — “this principle calls for the establishment of one authority figure for each designated task of the organisation; this person has the authority to co-ordinate all plans concerning that task.”

This principle is absent in various government agencies: Since different agencies develop separate plans on the same topic, no single agency or person is in control of the task nor can it co-ordinate plans.

c. A Formal Decision-Making Structure:

The organising process helps develop a formal relation between the superior and the subordinate. This is done through the use of formal organisation charts. This allows the orderly progression up through the hierarchy for decision making and decision-making communications. So there will be no confusion as to the responsibility of an organisation member (i.e., what he is in charge of).

d. A Wider Scope for Achievement:

The goal of an organisation is to accomplish some purpose that individuals cannot by themselves, acting alone. It has been observed that groups of two or more persons working together in a co-operative, co-ordinated way, can achieve more than what one is capable of achieving independently. This concept is known as synergy.

A Megginson has puts: “The cornerstone of organising is the principle of division of labour that allows synergy to occur.” In management it goes by the name specialisation, whereby employees (and managers) carry out the activities they are more qualified for and adept at performing.

The modern age is the age of division of labour and its corollary — specialisation — and in a modern corporation there is specialization between employees and managers. This leads to greater efficiency of human and material resources and conduces to increased productivity.

Excessive division of labour may have some undesirable consequences such as fatigue, monotony, boredom, and loss of motivation. All these may result in inefficiency.

By applying the organisation process, management is able to increase the possibilities of achieving a functioning work environment. So the next question is: What does this organising process consist of? We may now examine its components.

3. Organisation Design Process:

Organisation design is concerned with the unique interrelationships among the components of an organisation. Organisation are seldom, if ever, designed and then left intact. Instead, most organisations change constantly or are under a constant and gradual process of evolution as situations, people, and other factors vary.

The Bureaucratic Model of Organisation Process:

At the core of Max Weber’s writings was the bureaucratic model of organisation design. Weber suggested that a bureaucracy is an organisation structure based on a legitimate and informal system of authority.

Weber viewed a bureaucratic form of organisation as logical, rational and efficient. He offered the bureaucratic model as the normative framework to which all organisations should aspire, the ‘one best way’ of doing things.

Six Characteristics:

An ideal bureaucracy has the following six characteristics:

1. Tasks are divided into several highly specialised jobs and each position should be filled by an expert.

2. A rigorous set of rules has to be followed to insure predictability, eliminate uncertainty in task performance and ensure that task performance is uniform.

3. There are clear authority-responsibility relationships that have to be maintained. The organisation should establish a hierarchy of positions or offices such that a chain of command from the top of the organisation to the bottom is created.

4. Superiors take an impersonal attitude in dealing with subordinates. Especially, they should maintain appropriate social distance between themselves and their subordinates.

5. Employment and promotions in the organisation should be based on technical expertise. As a corollary, employees should be protected from arbitrary dismissal. A high level of loyalty should, therefore, develop.

6. Lifelong employment is taken as an accepted fact.

The concept of bureaucracy was first applied in the context of public administration. But it can now be applied in private organisations as well.

There are various examples of bureaucracy. But the best examples of contemporary bureaucracies are government agencies and universities. Both deal with large numbers of people who must be treated equally and fairly. Hence rules, regulations and standard operating procedures are necessary.

Strengths and Weaknesses:

The bureaucratic model of organisation has two primary strengths:

1. Prima facie, several of the elements of the bureaucratic model (such as division of labour, reliance on rules, a hierarchy of authority, and employment based on expertise) may improve efficiency.

2. Secondly, the bureaucratic model is the starting point for most later research and writings about organisation design.

Unfortunately, the pursuit of an ideal bureaucracy also has three major disadvantages:

1. The bureaucracy tends to be inflexible and rigid.

2. Human and social processes within the bureaucracy are neglected.

3. The assumptions Weber made about loyalty and impersonal relations are unrealistic.

No doubt, the bureaucratic model of organisation design was an important milestone in the development of management theory. As environments became more complex, our understanding of behavioural processes more complete, and employees and managers more sophisticated, the bureaucratic model gave way to other perspectives, which may now be discussed.

Behavioural Perspective: Strengths:

Just as the classical approach to organisation design paralleled the development of scientific management, the human relations movement encouraged a behavioural approach to organisation design. The best known and most important behavioural approach is Likert’s System 4.

Likerts’ System 4 Organisation:

Rensis Likert found on the basis of his own empirical studies conducted at the University of Michigan that organisations that hewed to the bureaucratic model tended to be less effective, whereas effective organisations paid more attention to developing work groups and were more concerned about behavioural and social processes.

Likert ventured to describe organisations in terms of eight key dimensions or processes: leadership processes, motivational processes, communication processes, interaction processes, decision processes, goal-setting processes, control processes, and performance goals.

At one extreme, Likert identified a form of organisation he called System 1. In various ways a System 1 organisation is similar to an ideal bureaucracy. In such an organisation, motivational processes are assumed to be based on economic factors, and interaction processes are closed and restricted.

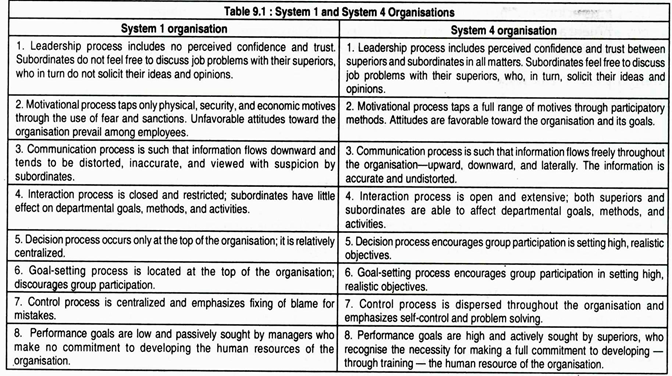

This means that communication is relatively formal and primarily job-related. The main characteristics of the System 1 organisation are summarised in Table 9.1.

Table 9.1 also summarises the characteristics of Likert’s other extreme form of organisation design, called System 4. The two most notable features of a System 4 organisation are that: (1) it uses a wide variety (range) of motivational processes and that (2) interaction processes are open and extensive. People communicate with one another freely (without any reservation), everyone talks to everyone else, and so on.

Other distinctions between the two types of organisations are shown in Table 9.1. In between these two extremes lie the System 2 and System 3 organisations, each of which is some combination of System 1 and System 4 characteristics.

Suggestion:

Likert suggested the adoption of System 4 by all organisations. To be more specific, he suggested that managers should emphasise supportive relationships, establish high performance goals and practise group decision-making to achieve the System 4 state.

By adopting the System 4 design many organisations succeeded in improving direct and indirect labour efficiency and product quality, while at the same time reducing tool rates and scrap costs.

The Linking Pin Role:

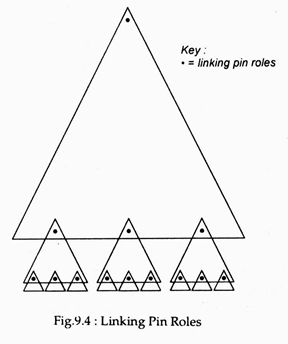

Likert made another important contribution. He identified, in the context of behavioural perspective on organisational design. Linking pin roles. According to Likert, every management position is linked to two groups of positions: a higher- level group or lower-level group of which the manager is the head. Thus, the manager can be viewed as a linking pin between levels of the organisation (See Fig.9.4).

This new and novel concept focuses attention on the role that managers at the middle levels of an organisation play in coordinating and communicating the activities of higher-level and lower- level managers.

Strengths and Weaknesses:

The behavioural approach to organisation design has one major strength and one major weakness. On the positive side, it lays stress on behavioural processes in organisations.

As Griffin has put it:

“whereas the classical perspective treated people like components of a large machine and minimised the importance of any one person, the behavioural model recognised the individual value of an organisation’s employees.” In truth, Likert and his associates paved the way to a more humanistic perspective.

On the negative side, the behavioural approach to organisation design, like the classical approach, was based on the premise that there is only one best way to design organisations. This ‘one best way’ view is now called a universal approach. This means that the ideas are assumed to be universally true. Thus, the bureaucratic world is also universal in nature.

Recent studies have indicates that numerous situational factors or contingencies affect a particular type of organisation design. This means that what works for one organisation may not work for another. This is why universal models like bureaucracy and System 4 have been largely supplemented by newer models that give due consideration to these contingency factors.

The contingency view of organisation design refers to the belief that the design that is appropriate for an organisation depends on a variety of situational factors.

Three such factors are:

(1) key variables inside the organisation,

(2) key variables outside the organisation, and

(3) the organisation’s strategy.

4. Internal Contingency Factors: Technology:

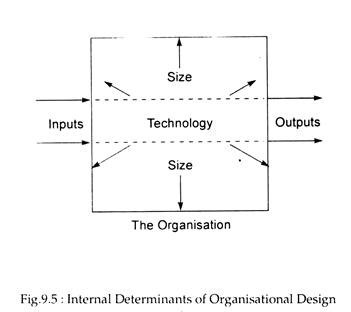

Factors internal to the organisation — those within its own boundaries — have a decisive effect on various structural components. See Fig. 9.5. Two important internal factors that may influence the design of an organisation are the technology of the organisation and its size.

Technology:

Technology is defined here as the common process used by an organisation in transforming inputs (such as materials or information) into outputs (such as products or services). Most people visualise assembly lies and machinery when they think of technology. But the term can also be applied to processing information.

Technology often — if not always — plays an important role in determining organisation design. As future technologies become more and more diverse and complex, managers should pay closer attention to the relationship between technology and organisation structure. However, the size of an organisation is also affected by another factor, viz., organisation size, to which we may turn now.

Size:

Organisations often change as they become larger. For example, they tend to departmentalise by product rather than function. Organisation size is normally defined in terms of the total number of full-time or equivalent employees.

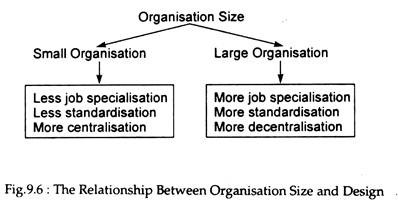

From various empirical studies made in recent past, the following generalisations about organisation size and design may be made:

1. The larger an organisation becomes, the more job specialisation is likely to be practiced.

2. The larger an organisation becomes, the more standard operating procedures, rules, and regulations are likely to be imposed.

3. The larger an organisation becomes, the more decentralised it is likely to become.

These key relationships are illustrated in Fig. 9.6.

5. External Contingency Factor: Environment and Information Processing:

The external environment of business affects organisation design in more ways than one. Organisation design is also affected by information-processing needs. These relationships are illustrated in Fig.9.7.

Environment of an Organisation:

The relationship between environment and organisation has been of considerable concern to management theorists and practising managers. Contemporary research has identified two types of environment: stable and unstable. While a stable environment is one that remains relatively constant over time, an unstable environment is subject to uncertainty and rapid change.

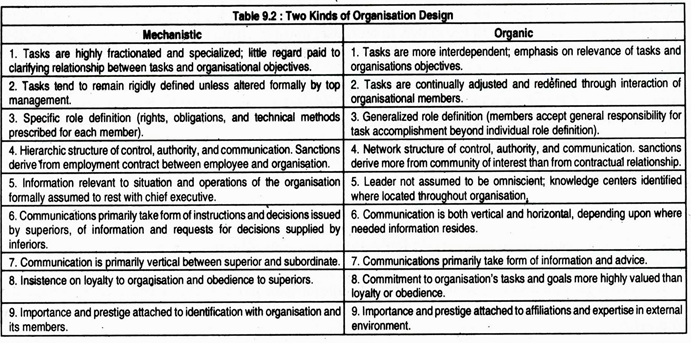

Furthermore, as a general rule, organisations operating in stable environments tend to have a different kind of design from organisations operating in unstable environments. The two kinds of organisation design that have emerged, summarised in Table 9.2, are called mechanistic and organic.

A mechanistic design, which resembles the bureaucratic world, is generally associated with stable environments. Being free from uncertainty organisations could structure their activities in rather predictable ways via rules, specialised jobs and centralised authority.

An organic design, on the other hand, is useful in unstable and unpredictable environments. The constant change and uncertainty of such environments usually dictate a much higher level of fluidity and flexibility.