Making Organizations more Effective: A Definitive Guide!

Authority:

All managers in an organisation have some sort of authority. But the degree of authority differs depending on the levels of management they occupy in the organisation structure. Authority is one of the most important tools of a manager.

Authority is power that has been legitimised by the organisation — the right to command others to act or not to act in order to reach certain specific objectives. It can be described as the right to commit resources (that is, to make decisions that commit resources of an organisation) or the legal (legitimate right to give order — to instruct someone to do or not to do something).

For instance in 1938 Henry Ford, Chairman of Ford Motor Company, fired Lee Iacocca as its President. Ford’s authority was derived from the company’s board of directors, which acquirers its power from the shareholders.

Authority is the ‘glue’ that holds the organisation together. It provides the means of command. It results from the delegation or shifting of power from upper to lower positions in the organisation. How the question is: how does a manager acquire authority?

Sources of Authority:

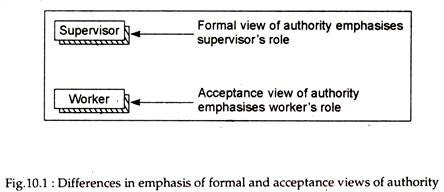

There are two contradictory views regarding the source of authority and on the basis of these two theories have been developed, viz., the formal theory and the acceptance theory.

Formal view of authority:

According to this theory authority is conferred; authority exists because it was granted to someone. This theory seeks to trace the origin of authority upward to its ultimate source, which for business organisations are the owners or stockholders.

As Plukett and Attner have rightly commented: “authority is rested in a manager because of the position he or she occupies in the organisation. Thus authority is defined in each manager’s job description or job charter. The person who occupies the position has its formal authority as long as he or she remains in the position. As the job changes in scope and complexity, so should the amount and kind of formal authority possessed.”

Acceptance view of authority:

Even though a manager has formal or legitimate authority, the key to effective management is the willingness of employees to accept the legitimate authority. The acceptance theory of authority focuses on the employee as the key to the manager’s use of authority. It disputes that authority can be conferred.

According to this theory, a manager’s authority originates only when it has been accepted by the group or individual over whom it is being exercised. As Chester Barmard put it: “If a directive communication is accepted by one to whom it is addressed, the authority for him is confirmed or established.” The implication of this definition is that acceptance of the directive becomes the basis of action.

In other words, disobedience of such a communication by an employee is a denial of its authority for him (or her). It, therefore, follows from Barnard’s definition that the decision about whether an order authority lies with the persons to whom it is addressed and does not reside in ‘persons of authority’ or those who issue those orders. This point is illustrated in Fig.10.1.

In short, the acceptance theory suggests that a manager’s authority does not exist until it is accepted and acted on. However, in practice it is the interaction of formal authority with employee acceptance that produces positive results.

According to the formal theory authority is a right that has been granted to a manager by the organisation. However, we will soon observe that the acceptance theorists often confuse authority with power or leadership, which involves the ability of a manager to influence subordinates to the point at which his (her) authority is accepted.

But these theories (known as behaviourists) make the important point that to be effective; managers are certainly very dependent on acceptance of their authority through the use of effective leadership.

Authority and Power:

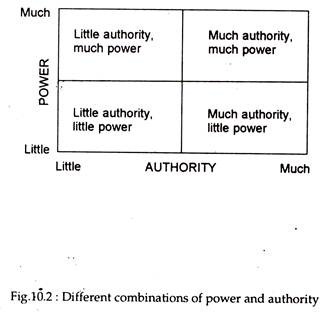

In actuality it is observed that two managers occupy identical positions of formal authority, with the same degree of acceptance of this authority by their employees. Yet they are not identical, i.e., equally effective, in the organisation. The reason is that one manager may not possess the power to be as effective as another manager.

In truth, the manager’s possession of authority is not sufficient in itself to assure that subordinates will respond to the manager’s desires and instruction (directives). In other words, having authority is not enough to assure compliance with the desires of a manager. To be effective, the manager must also exercise power.

Power is the ability to exert influence in the organisation, i.e., on individuals, groups, decisions or events. The possession of power can enhance the effectiveness of a manager by enabling the manager to influence people so that something beyond (more than) the scope of formal authority is achieved.

The difference between power and authority is that the former is personal (it exist because of the person) and the latter is positional (it will not be there when the incumbent leaves). Fig. 10.2 shows various combinations of power and authority that may exist in an organisation.

It is widely believed that there are various abuses of power. There is a famous saying that ‘power tends to corrupt, and absolute power corrupts absolutely. But in recent years there has been a growing awareness that power is not necessarily bad.

In fact, the use (exercise) of power is absolutely for the effective achievement and accomplishment of individual, and organisation goals. Davil Mc-Clelland’s research on motivation shows that a high need for power is an important characteristic of successful managers.

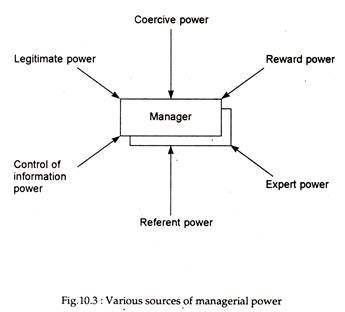

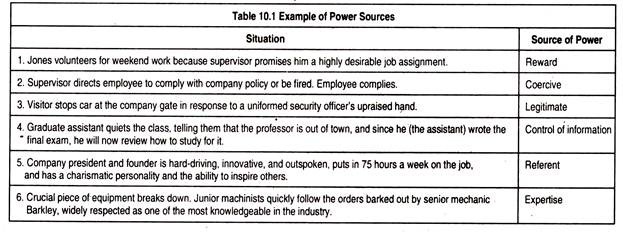

Sources of Power:

There are diverse sources of power. Fig. 10.3 shows that there are six different sources of managerial power.

These are summarized below:

1. Reward Power:

It stems from the number of positive rewards (money, job protection, and the like) that a potential leader is supposed to control. In fact, the ability to grant favours or cause discomfort to others can serve as a basis of power. Preferential treatment, overtime, and expediting service can provide the means to influence behaviour and results.

2. Coercive Power:

Such power originates from people’s perceived expectation that punishment (being fined, reprimanded, or the like) will follow if they do not comply with the aims of a potential leader. For example, slowing down service can provide the means to influence behaviour and results.

The private secretary to the boss normally possesses power well beyond the scope of the job. He (she) can control the boss’s calendar and ration out the time on the calendar. This is a prime example of reward or punishment.

3. Legitimate or Position Power:

It develops from internalized values that a leader has a legitimate right to influence subordinates. Under this view, an employee is under the obligation to accept that influence because a person is designated ‘boss’ or leader or because service implies subordination.

In fact, holding a managerial position with its accompanying authority provides a manager with a power base. The manager is in a position to use power because of the right of the position. The higher a manager is in the organisational hierarchy, the greater is the ‘perceived power’, that is, power that subordinates think exist (whether it really exists or not).

4. Control-of-information Power:

It derives from knowledge that others do not have. Some people use this method by either giving or withholding needed information.

5. Referent or Charismatic Power:

This power is based on people’s identification with a potential leader and what that leader stands for or symbolizes. It is based on the kind of personality an individual has and how that personality is perceived by others. The important factors in the exercise of such power are personal charisma, charm, courage, and other traits. The adoration by others and desire to identify with and imitate a person are the indicators of this person’s power.

6. Expert Power:

This power results from a potential leader’s having expertise or knowledge in an area in which the leader wants to exert influence on others. It is possessed by persons who have demonstrated their superior skills and knowledge. They know what to do and how to do it. Others expect to stay on this expert’s good side.

How Power Expands:

There is a feeling among some managers that if power (the wherewithal to influence others, such as knowledge of sources or access to authority) is shared with others (subordinates) it gets diluted. This is an unproved and probably false belief. Rather the converse is true: the best way to expand power is to share it, for power can grow, in part, by being shared. However, it is to be noted at the outset that sharing power is completely different from giving or throwing it away inasmuch as delegation does not necessarily mean abdication.

Manager’s need for power:

Effective managers have a high need for power but that need is oriented toward the benefit of the whole organisation. Furthermore, the need for power is stronger in these managers than the need to be liked by others.

Thus a manager must, of necessity, be willing to play the influence game in a controlled manner. However, this does not necessarily imply that the managers in general make their subordinates feel stronger rather than weaker. But a true authoritarian would make people feel weak or totally powerless.

Managerial style and need for power:

Another important element in the profile of a manager is his (her) style. A study made by David McClelland on managerial style reveals that those managers whose employees had a higher morale scored higher on the democratic or coaching styles of management. The fact that the managers were also higher in power motivation implies that they express their power motivation in a democratic manner -which is more likely to bear fruit.

Breadth of authority and power:

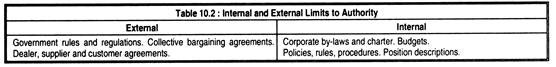

All people in an organisation have certain codes, restrictions, or limits placed on their authority. This point is shown in Fig. 10.4.

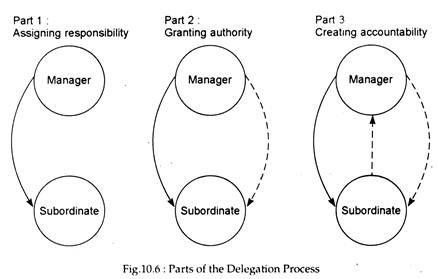

No doubt the executives of most big companies are very much powerful. But they often lack absolute authority. Some of the limits are imposed by certain factors which are external to and beyond the control of the firm or its managers.

Such factors include various state regulations and controls such as industrial licensing system, policy of reservation, environmental protection laws, occupational safety laws, contracts with dealers and suppliers, collective bargaining agreements and so on.

Managerial authority is also limited by certain internal factors such as the memorandum and articles of association of an organisation, its charters and bylaws, policies, rules, procedures, budgets, positions and powers of different people in the organisation and so on. For example, the vice-president (sales) may have the authority to spend Rs. 50,000 per annum without consulting the president, whereas a first-line supervisor may be permitted to spend only up to Rs. 100 for needed supplies without obtaining any permission from the department head.

Fig.10.4 shows the limits to authority. It is shown that the scope of authority is broader at the top of an organisation and narrower at the lower levels of the chain of command.

Responsibility and Accountability:

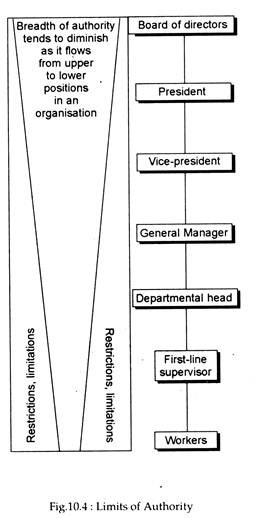

Two important concepts which are often used in organisation bahaviour used in organisation bahaviour are ‘responsibility’ and ‘accountability’. The former refers to the obligation that is created when an employee accepts a manager’s authority to delegate tasks or assignments.

The latter refers to the fact that employees will be judged by the extent to which they have fulfilled their responsibilities. One is accountable to his superior in the sense that one’s supervisor (immediate boss) can confer either punishment or reward, depending on how well one has exercised responsibility.

Responsibility and Accountability cannot be delegated:

A major organisational principle is that no person can escape his (her) responsibility or accountability by shifting it to another person. Or, to put it in a different language, no one can assume — or accept — another person’s responsibility for performing a duty. A manager should be able to appreciate that delegating his authority to another person does not relieve him of the original responsibility and accountability.

Fig. 10.5 : Flows of authority, responsibility and accountability

In fact, a whole network (spectrum) of responsibility-accountability transactions can occur when authority to carry out tasks is delegated to lower organisational levels, as Fig. 10.5 shows.

Equality of Authority and Responsibility:

A very well-known and important principle of management is that people in organisations should be assigned or delegated sufficient authority so as to enable them to carry out their responsibilities. If, for instance, the responsibility of a production manager is to maintain a certain rate of production (or production capacity) he (she) must be given sufficient liberty to make decisions that affect production capacity.

Difficulty of achieving equality:

In theory the equality of responsibility and authority makes good sense, but in practice it is very difficult to achieve. Even some leading management experts go to the extent of arguing that it is even unrealistic, in today’s management world, to attempt to achieve it.

Some proximate reasons for this seem to be government laws and regulations, the presence of trade unions and pressure groups (like chambers of commerce or trade associations) and the network of dependence that exists in organisations. In practice, it is observed that most managers—even efficient ones—are entrusted with more responsibility than authority.

Another major reason for the non-equalization of authority and responsibility seems to be the reluctance of higher-level managers to delegate to their subordinates. What is of paramount importance is that everybody should be considered in determining actions by which all are affected.

In other words, it is fundamental that individuals should have a range of authority to exercise judgement and latitude in making decisions about those major results for which they will ultimately be held accountable.

Effect of time on equality:

To sum up, there is equalisation of authority and responsibility in the long run, for if authority is delegated, it cannot be taken back. But in the short run, a manager’s responsibility invariable exceeds his (her) authority because of the nature of delegation. For example, whenever manager X delegates authority during the period of delegation.

Yet manager X’s accountability to his (her) supervisor remains unchanged. Therefore, manager X’s responsibility is greater than the authority available to be used at that time. At a later stage, manager X can take back the authority, but anything manager y does while exercising that authority is still the responsibility of both manager X and manager Y. In other words, responsibility is shared.

Delegation of Authority:

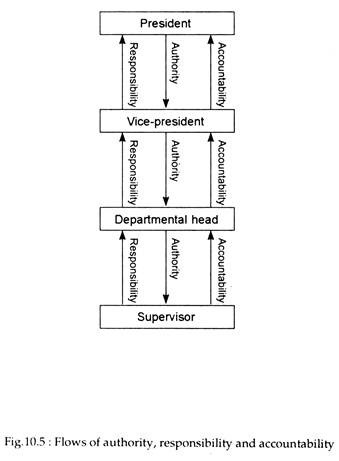

The word ‘delegation’ is a very important concept of management. It describes the way in which formal authority is passed to another person. To be more specific, delegation of authority is the process by which managers allocate authority downward to the people who report to them.

As Griffin has put it: “Delegation involves the establishment of a pattern of authority between a superior and one or more subordinates. Specifically, delegation is the process by which the manager assigns a portion of his (her) total work load to others”. Superiors delegate, or pass authority down, to subordinates so as to facilitate work being accomplished.

The following/our actions occur when delegation takes place:

Firstly, the delegator assigns objectives or duties to the lower-level employee.

Secondly, the delegator grants the authority necessary to accomplish the objectives or duties.

Thirdly, acceptance of delegation, whether implicit or explicit, creates an obligation or responsibility.

Fourthly, the delegator holds the employee accountable for results.

One of the proximate causes of the difference between successful managers and unsuccessful ones is ineffective delegation.

Reasons for Delegation:

Delegation may be necessary when managers are absent from their jobs or it just may be the philosophy of the manager in order to develop subordinates, but a deeper analysis reveals that there are four major reasons for delegating:

Prima facie, delegation enables managers to derive the advantages of division of labour and specialisation. In other words, it enables managers to accomplish more than if they attempted to handle every task personally.

Secondly, delegation permits managers to focus their energies on the most crucial, high-priority tasks.

Thirdly, delegation also enables subordinates to grow and develop, even if this implies learning from their own mistakes.

Fourthly, delegation is needed because managers do not always have the knowledge needed to make decisions. In most cases managers appreciate the nature of a problem but they may not know enough about the problem so as to take a rational decision.

Another reason — and according to some writers on management, the primary reason — for delegation is to enable the manager to get more work done. Subordinates help ease the manager’s burden by doing major portions of the organisation’s work.

In some situations too, a subordinate may have more expertise in addressing a particular problem than the manager does. The manager may have had special training in developing computer information systems or may be more familiar with a particular product line or geographic area.

Finally, delegation helps develop the subordinate for future promotion. By participating in decision-making and problem solving, subordinates come to learn about overall operations and improve their managerial skills.

Parts of the Delegation Process:

Fig. 10.6 shows the nature of the delegation process in an organisation. It shows that three things are delegated by a manager to a subordinate. First, the manager responsibility, or gives the person a job to do, such as preparing a report. Along with the assignment, the individual is also given the authority to do the job.

The manager may give the subordinate the power to acquire needed information from confidential files or to direct a group of other workers. Finally, the manager requires accountability from the subordinate. That is, the subordinate has an obligation to carry out the task assigned by the manager.

These three parts do not, of course, follow in rigid 1-2-3 order. Indeed, when a manager and a subordinate have developed a good working relationship, the major parts of the process may be implied rather than stated. The manager may simply mention that a particular job must be done.

A perceptive subordinate may realise that the manager is actually assigning the job to him. From past experience with the boss, he may also know, without being told, that she has the necessary authority to do the job and that he is accountable to the boss for finishing the job as ‘agreed’.

Application of the Concept:

Whatever may be the reason for delegation, its application creates the following sequence of events:

1. Assignment of tasks:

In the first stage, specific tasks or duties that are to be undertaken are identified by the manager for assignment to the subordinates.

The subordinate is then approached with the assignment.

2. Delegation of adequate authority:

To enable the subordinates to complete the duties or tasks, the manager should delegate sufficient authority to the subordinate so that the task is just completed.

3. Accountability or responsibility:

Responsibility has been defined as the obligation to carry out one’s assigned duties to the best of one’s ability. However, responsibility is not delegated by a manager to an employee. Instead the employee becomes obligated when the assignment is accepted.

Just as rights and duties go hand in hand, responsibility and accounting are often treated as the two sides of the same coin. As Plunkett and Attner put it: “the employee is the receiver of the assigned duties and the delegated authority; these confer responsibility as well.”

4. Creation of responsibility:

Accountability is having to answer to someone (the boss) for one’s actions. It implies accepting the consequences — either credit or blame. When the subordinate accepts the assignment, he (she) will be held accountable or answerable for actions taken.

A manager is almost always accountable for the use of his (her) authority and performance. Furthermore, the manager is also accountable for the performance of and actions of subordinates.

This four-step process makes one thing clear at least: the process of delegation produces clear understanding on the part of the manager and of the subordinate. In short, it is essential on the part of the manager to take time to think through what is being assigned and to confer the authority necessary to achieve results. The subordinate, in accepting the assignment, becomes obligated (responsible) to perform, knowing it clearly that he (she) is accountable (answerable) for the results.

Problem in Delegation:

It goes without saying that delegation is crucial to effective management but in practice, we observe that some managers do fail to delegate and others delegate weakly. In other words, problems often arise in the delegation process.

Some proximate reasons for these are the following:

1. The manager often develops a feeling that they are more powerful if they retain decision making privileges for themselves.

2. The manager does not want to expose himself to the risk that employees will exercise authority poorly.

3. The manager may be so dis-organised that he (she) is unable to plan work in advance and, as a result, be unable to delegate appropriately.

4. There is also a feeling among most managers that employees lack the ability to exercise good judgement. A manager often feels that he can perform a task better than his subordinate. Since he considers himself indispensable for a job he is reluctant to delegate.

5. The manager may not trust the subordinate to do the job well.

6. Finally, there is an apprehension among some weak-minded managers that employees may out perform — they will perform so effectively that the managers will be overshadowed and their own positions will be threatened. The manager may worry that the subordinate will do too well and pose a threat to his (her) own advancement.

However, the supervisors alone should not be blamed for their failure to delegate. In other words, all six barriers to effective delegation may not always be founded in managers and supervisors.

The problem may lie with the employees. In fact, employees themselves may resist accepting delegation of authority.

There are six reasons why some subordinates are reluctant to accept delegation:

Firstly, if authority is delegated the employees feel that they are entrusted with added responsibilities. They also feel that delegation adds to their accountabilities. An employee usually finds it easier to go to his (her) manager to resolve a problem than to make the decision himself (herself).

Secondly, there is always the danger that an employee will exercise his new authority poorly and invite criticism. This is what most employees attempt to protect themselves from.

Thirdly, subordinates are afraid that failure will result in a reprimand or disciplinary action.

Fourthly, they may perceive that there are no rewards for accepting additional responsibility.

Fifthly, they may simply prefer to avoid risk and, therefore, want their boss to take all responsibility.

Finally, most employees lack self-confidence and feel that if they are granted greater decision-making authority they are always under pressure.

How to solve these problems?

There are no easy solutions. Essentially it is a matter of organisation communication. It is not enough for subordinates to understand their own responsibility, authority and accountability. It is equally vital for the manager to recognise the value of effective delegation.

As R. W. Griffin has rightly commented: “With the passage of time, subordinates should develop to the point where they can make substantial contributions to the organisation. At the same time, the manager should recognise that a subordinate’s satisfactory performance is not a threat to his (or her) own career, but an accomplishment on the part of both the subordinate who did the job and the manager who trained the subordinate and was astute enough to entrust the subordinate with the project. Ultimate responsibility for the outcome, however, continues to reside with the manager, who is, in turn, accountable to a higher-level manager”.

Conclusion:

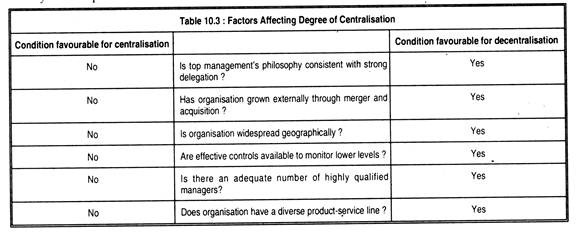

However, the conclusion is that delegation is of fundamental importance to effective management. Delegation is considered to be used effectively if an employee can answer affirmatively all the questions raised in Table 10.3.

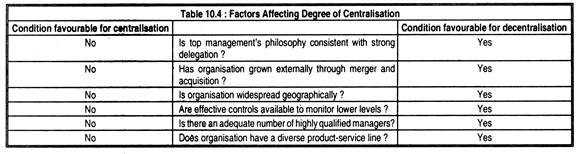

Factors Determining the Degree of Decentralisation:

What factors determine an organisation position on the decentralisation-centralisation continuum? The degree of centralisation or decentralisation within an organisation depends on a number of different but interrelated factors listed in table 10.4. These factors and some others may now be briefly reviewed.

1. The philosophy of management:

Those top managers who are highly autocratic in their approach usually desire strong centralised control. They prefer to be surrounded by a strong central staff and reserve the most important and major decisions for the highest organisational levels. On the contrary, some managers highly value the virtues of a decentralized organisation.

In a large reputed corporation like General Electric decentralisation is used as a way of preserving and enhancing its contribution, while, at the same time, achieving the flexibility and ‘human touch’ popularly associated with, but not always achieved by, smaller organisations.

Decentralisation may be achieved in terms of products, geographical locations and functional types of work. But a big company also decentralizes the responsibility and authority for making business decisions. In general, the greater the number of decisions made at the lower levels of management, the more decentralized a company is.

Likewise, the more important the decisions made at lower levels, the greater the decentralisation. Purchasing decisions are a good measure. If the limit at the first level is Rs. 100,000 compared to another business in the same industry where the limit may be Rs. 1,000 the first company is supposed to be more decentralized.

In a large enterprise the responsibility for making decisions is put not with a few top level executives but with individual managers and functional employees who have the best possible information necessary to arrive at sound decisions and take prompt action.

When such authority is delegated — along with the required responsibility and accountability — and according to carefully planned organisation of work, employees feel that they have challenging and dignified positions. They, in turn, bring out their full resources and enthusiastic co-operation for making organisations more effective.

2. History of organisational growth:

In general organisations that grow internally tend toward centralisation because this was their basic approach to start with. For example, Hindustan Motors grew internally and now tend to have higher degrees of centralisation than organisations that have grown externally through merger with and acquisition of other firms (such as the I.T.C Ltd.).

There are so many examples of moderately effective (or even unprofitable) firms that are loosely managed and are acquired by strong companies with the expectation that strong centralisation from the parent company will make it economically viable.

3. Geographical dispersion:

The more widely dispersed the operations of a company geographically, the greater the degree of decentralisation. For example. Nestles Corporation, which operates throughout the world, is the example of a highly decentralized corporation. In this context we may note that the more flexible the interpretation of company policy at the lower levels, the greater the degree of decentralisation. Decentralisation permits lower-level managers to have a greater degree of decision-making latitude and to adapt to local conditions affecting their units.

4. Availability of effective controls:

In general, organisations that lack effective measure of controlling lower-level units will tend toward higher centralisation since they find it very difficult to monitor the performance of lower-level units. This usually happens in case of maintenance departments.

In this context L. C. Megginson has commented that “information technology has enabled top management to move toward larger amounts of centralized decision making. But, on the other hand, the availability of more effective controls for top management has also made possible a greater degree of decentralized decision-making.”

5. Quality of managers:

Decentralisation requires greater number of more qualified managers, since managers will be permitted to enjoy greater latitude in making their own decisions at lower levels. Thus the less a subordinate has to refer to his (her) manager-prior to a decision, the greater the decentralisation.

On the contrary, in organisations in which there is a scarcity of highly qualified managers and specialists, the strategy usually followed is to centralise the decision-making process {i.e., to maintain decision-making authority at higher organisational levels.)

6. Diversity of products and services:

Finally, the diversity of products and services also exerts some influence on the degree of decentralisation achieved in an organisation. In short, the more diverse the range of products or services offered, the greater the tendency toward decentralisation. On the contrary, the narrower the product and service range, the more feasible centralisation is.

7. The external environment:

Usually, the greater the complexity and uncertainty of the environment, the greater the tendency to decentralise.

8: History of the organization:

Firms normally have a tendency to do what they have done in the past. So there is likely to be some relationship between what an organisation did in its earlier history and what it chooses to do now in terms of centralisation and decentralisation.

9. Nature of the decision:

The costlier and riskier the decisions, the greater the pressure there is to decentralise.

10. Abilities of lower-level managers:

In those organisations where lower-level managers do not have the ability to make high-quality decisions, there is likely to be a high level of centralisation. If lower-level managers are very well qualified, top management can take advantage of their talents by decentralising; in fact, if top management fails to do so, talented lower-level managers are likely to quit.

The Final Diagnosis:

Harold Koontz has pointed out that there is a set of clear-cut guidelines for a manager to use in determining whether to centralize or decentralise. Many successful organisations practice decentralisation. Equally successful firms have tended to remain centralised. Even within the same industry, different formulas for success have been applied. The truth is that the appropriate degree of decentralisation is that which fits the circumstances.

Wanted: A Contingency Approach:

In short, various factors affect the degree of centralisation and decentralisation in an organisation. Furthermore, the degree varies within different divisions or departments of the same organisation and must change according to the internal and external environment of the organisation. This is the approach which most organisations should follow.

Relationship of Centralisation to Span of Management (Control):

One may finally note that a company’s philosophy of centralisation or decentralisation in decision-making is likely to influence the span of control of subordinate managers. As a general rule a philosophy of decentralized decision making implies that the span of management has to be widened for each manager. The reason is easy to find.

If decision-making is forced down to subordinates, a manager can save a considerable amount of time which can be fruitfully utilized for more useful and serious purposes. Such a situation also generally implies that there are fewer levels of management in an organisation.

By contrast, if managers believe in a philosophy of centralized decision-making the result will be a narrower span of control and more levels of management.

If management philosophy is to have managers make the majority of decisions, the managers will closely supervise their subordinates and delegate little. This will lead to an increase in the number and length of contacts. Consequently, the span of control will be narrowed.

Although in theory we find a strong interrelationship of decision making and span of control, in practice, something else happens in most cases. Managers with wide spans of control may choose not to delegate authority; and on several occasions they are not as effective as they could be if they delegated.

Furthermore, the problem with this generalization is that various other factors can exert considerable influence in determining how many subordinates a manager has.

Defining Responsibility:

To make an organisation more effective there is need to co- ordinate the activities of different people and departments. The need for co-ordination in felt primarily because management does not define responsibilities effectively. People in organisations sub-systems have to face great difficulty in achieving the needed degree of co-ordination when they do not really know who is actually assuming responsibility and exercising authority.

Thus the issue of defining responsibilities is an important one. Management can use various techniques to define responsibilities so as to actively involve members of an organisation in its co-ordination effort. Three such techniques are:

(1) Responsibility Charting,

(2) Role Negotiation and

(3) MAPS.

Moreover, new organisational positions may be created and line and staff conflict resolved by enhancing the degree of co-ordination.

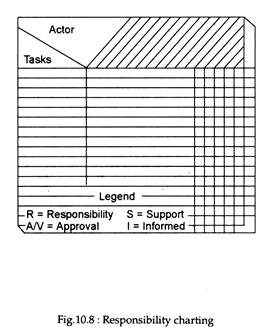

1. Responsibility Charting:

We may recall that responsibility refers to the obligation that is created when an employee accepts a manager’s authority to delegate tasks or assignments. We have already noted that there is a close relation between authority and responsibility.

A responsibility chart is a nice way of summarizing the relationship between tasks and actors (performers) See Fig. 10.8. The chart lists the activities that must be completed or the decisions that must be made and the individuals who are responsible for each of them. On the vertical axis we show the tasks and on the horizontal axis we show the actors. This chart thus describes the various roles that each individual plays in the activities or decisions.

The following four roles are important:

1. The individual is responsible for the activity (decision).

2. The individual must approve the activity or decision.

3. The individual must be consulted before completing the activity of making the decision.

4. The individual has to be informed about the activity or the decision.

The most important point about this chart is that it helps to eliminate jurisdictional disputes (conflicts) between (among) individual and departments. Moreover, it is very much useful in resolving ambiguities in the decision process. Sometimes, dual responsibilities are established so that more than one individual can be held responsible for making a major decision.

While evaluating the merit of such charting most managers have come to accept the belief that “co-ordination is typically enhanced when responsibility charting is employed. Organisational members can easily identify the relevant individuals in the decision process, and hence it is easier for them to co-ordinate their efforts and for management to follow up if the activities are not completed.”

2. Role Negotiation:

From our discussion of responsibility charting it appears that organisational members often experience great difficulty in coordinating activities, largely because they do not fully understand their respective responsibilities.

Such misunderstanding often leads to friction among the members of the organisation. Role negotiation is an important technique that can supplement the use of responsibility charting. If used properly, it can lead to clear definitions of tasks and the responsibilities associated with them.

The basic promise of the technique is that nobody gets anything without promising something in exchange (return). Organisational members meet at periodic intervals to list the kinds of decisions that they make and the individuals who contribute to them. They also criticize one another’s business behaviour, using the list of assets and liabilities developed previously.

3. MAPS:

A third approach to defining responsibilities is called Multivariate Analysis, Participation, and Structure (MAPS). Like the previous two techniques, it emphasizes the redefinition of tasks so that co-ordination can be maximized. The primary objective of this approach is to identify the independent clusters of tasks completed by the organisation. The second objective is to match the personal needs and work preferences of individuals with the tasks that must be completed.

Every modern organisation has to complete a number of tasks. The virtue of this technique is that by means of a complex statistical analysis, individuals are assigned to tasks according to their preferences for specific types of work and for working with other members in the organisation. If they dislike their new assignments, they are always permitted to change them.

The three techniques briefly reviewed above have one thing in common: they emphasize the redefinition of tasks and responsibilities so that co-ordination and co-operation are enhanced. Their basic theme is that tasks must be co-ordinated closely to achieve organisational effectiveness.

Establishing New Positions:

Another way of increasing co-ordination is by establishing new managerial positions.

The objective is twofold:

(1) More even distribution of work and

(2) More visible demarcation of responsibilities.

Two ways of establishing such positions are (a) creating a chief operating officer position, (b) setting up an office of the president.

Most private sector organisations are led by a company president, who is normally appointed by a board of directors representing the shareholders or owners of the company. Traditionally the president acts as the chief executive office (C.E.O.) and is responsible for both policy-making and strategic planning and for overseeing the daily operation of the corporation.

He usually acts independently, i.e., his decisions are not subject to approval by the Board unless they involve critical issues such as business ethics or the allocation of a significant amount of money. Thus the Board of Directors just serves as a oversight committee rather than as an operating unit of the company.

A preferable alternative is for the chairman of the board to serve as the C.E.O. of the company and ^e president to report directly to him. Under this arrangement the C.E.O. is involved in policy-making or strategic planning, but not in the day-to-day operations of the company, which are now overseen by the president in his new role as chief operating officer (C.O.O.).

This arrangement has an obvious advantage from the organisation’s point of view. It enables one to draw a clear distinction between policy-making and day-to-day operations. It also permits the board of directors to focus on strategic planning under the guidance of an experienced executive of the company who no longer has to worry excessively about the day-to-day operations of the company.

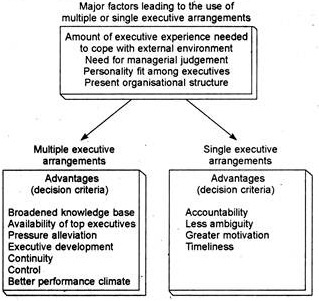

Most big companies become complex over the years. Consequently, one top executive or even two top executives (C.E.O. or C.O.O. find it difficult to be responsible for all the activities in which a company engages. To handle complex activities large organisations like the Texmaco (India) or Ford Motor Co. (U.S.A.) have periodically created a new office — the office of the president — to handle such complex activities.

Such an office consists of two or more chief executives with the same power, position and status. They divide the work among themselves and co-ordinate their efforts. Although in this office the chief executives are theoretically equal to one another, each of them primarily focuses on one major activity.

This arrangement often proves to be successful, especially in those situations where one chief executive cannot handle the huge volume of work alone. Fig. 10.9 summarizes and compares the major advantages of the traditional arrangement of a single top executive and those associated with the new arrangement of the office of the president.

Fig.10.9: Arrangement of office of the president

However, there are two inherent dangers in this approach. Firstly, the co-equal executives may fight among themselves when they apportion areas of responsibilities. Secondly, one chief executive may became dominant and may try to rule.

Line and Staff Positions:

Another way to improve co-ordination within the organisation is to distinguish clearly between line and staff rules or positions. This will enable organisational members to clearly recognise the degree of responsibility associated with each organisational position.

The concept of line and staff often confuses students and managers. To avoid this it is necessary to discuss the whole issue in detail. We may start with the distinction between the line and staff.

A line position is a position in the direct chain of command that is responsible for the achievement of an organisations goals. Line personnel are those whose work directly contributes to the accomplishment or organisational objectives. An example of this is the vice president of production or a worker who actually makes the product the firm sells.

On the other hand, a staff position is intended to provide expertise, advice and support for line position. Example of such personnel in large organisations are those in research, personnel, training, and industrial relation. The staff functions are usually under the jurisdiction of one individual (the vice-president) that is separate from that of the line organisation.

A staff executive can exercise a great amount of authority and responsibility within his own department. However, since the basic function of staff personnel is to advise and assist line personnel, staff work is normally treated as less important than line work. In most decision environments, line officers merely listen to the advice of staff officers and then make their own decisions. Staffs are usually subordinate to line personnel as in the publishing industry.

However, there are cases in which staff officers are more powerful and important than line personnel as in the railways or airways. In small and simple organisations, all or most of its members are line personnel. As the organisation grows over time, it usually begins to increase its staff personnel because of the complexity of the work; it is no longer possible to use line personnel alone.

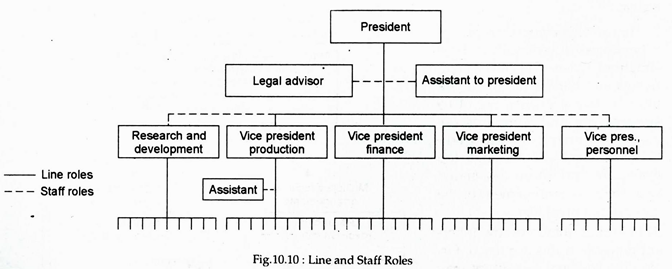

The distinction between a line position and a staff position is made clear in Fig. 10.10.

The president and the vice-presidents for production, finance and marketing are considered Line managers; they occupy a position in the direct chain of command and contribute directly to the firm’s goals. The assistant to the president and the assistant to the vice-president of production hold personal staff positions; they assist the individual manager in various activities.

The legal advisor and the vice-presidents of research and development (R&D) and human resources are also called professional staff, because they have special skills and because they work with many departments rather than just one individual. The vice-president of human resources, for example, would work with all of the other top managers to hire and train employees of their respective units.

We may make a detailed discussion of line and staff positions and start with the line organisation against this background.

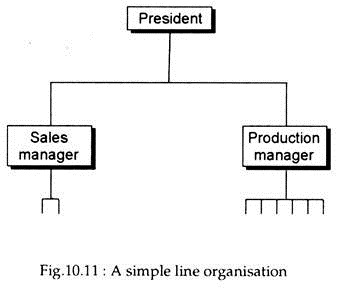

The Line Organisation:

The line organisation refers to those departments which are held directly responsible for accomplishing the major activities of the organisation. Suppose the objective of a hypothetical organisation is to produce and sell goods. Its line organisation will consist of the president, sales managers, and production manager, together with the employees who perform production and sales work in these departments.

Line departments are the departments set up to fulfill major organisational objectives. Such departments are headed by a line manager. Line departments normally include production (of goods and services for sales to a market), marketing (to include sales, buying, advertising, and physical distribution), and finance (acquiring capital resources). In functioning with the employees and departments under their control, line managers exercise line authority.

Fig.10.11 is illustrative of an organisation chart of a small manufacturing company that operates as a pure line organisation. It is observed that individuals in each department perform the major activities of production and sales.

Since each person in this type of organisation has to report to only one person, there is unity of command.

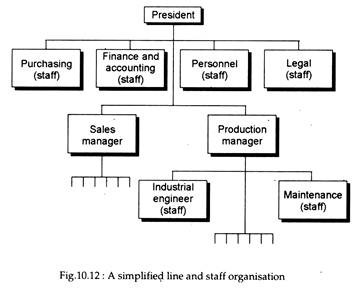

The Line-And-Staff Organisation:

When an organisation like the one shown in Fig. 10.12 continues to grow and becomes more and more complex, it becomes necessary to hire certain persons who do not directly perform the major activities of the organisation — production work and sales.

For instance, an accountant specialist may be recruited. He (she) will perform certain services for the line organisation such as keeping the books, preparing cost reports, billing customers, and so forth. Another position of a personnel manager may be created. He will be employed with a view to performing such functions as personnel recruiting/interviewing and screening of potential job candidates.

Another specialist might be an industrial engineer. His job is to aid the line organisation seeking to find improved work methods and practices. Still another might be purchase manager whose task is to help the line by handling all the orders for materials, equipment, and supplies. And another might be a maintenance specialist whose task is to help the line department by servicing and maintaining equipment. These new personnel, who do not perform line activities, are referred to as ‘staff.

It may be noted in this context that staff departments provide assistance to line departments and to each other. Through advice, service and assistance they indirectly assist the organisation in making money. On the basis of the special needs of the organisation traditional staff departments such as legal, personnel, computer services and public relations are created.

With organisational growth the need for expert, timely, ongoing advice becomes really critical. This need is fulfilled by creating a staff department if, of course, the organisation can afford it in terms of resources. In the success of a company staff departments play a vital role.

This new organisation structure will reflect the presence of both — line and staff as is illustrated in Fig.10.12. In this, an additional staff position — legal — is also shown. The result is the emergence of a line-and-staff organisation in which staff positions have added to the already existing line departments.The objective is to serve the basic line departments and help them accomplish the organisational objectives more effectively.

The basic point to note is that staff employees or staff departments refer to those that are not directly involved in the mainstream activity of the organisation or department. For example, maintenance specialists do not either produce a product or sell it in the market. The same statement is true of other staff specialists (members) such as accountants, purchasing agents, computer programmers, industrial engineers, or personnel specialists.

Importance of Line and Staff Roles:

The importance of line positions is that managers holding these roles are responsible for the ultimate performance of the organisation. In business firms, production, marketing and finance managers play the key roles in managing the enterprise.

The importance of staff positions may not be that obvious. But the expertise of staff managers is often just as important as that of line managers.

Types of Staff:

Staff employees are usually divided into two broad categories:

Personal staff and specialised staff:

It is the task of personal staff to give advice, render help and provide service to an individual manager. The ‘staff assistant’ usually works on a variety of tasks for the manager and is usually a generalist.

By contrast, specialised staff is created to advise, counsel, assist and serve the line and all elements of the organisation. The word ‘specialised’ carries the connotation that the function of a specialized staff is narrow, and such a staff is considered as an expert. His (her) expertise is made available throughout the organisation indiscriminately.

Some examples of such staff are personnel specialists, safety specialists, legal specialists, medical officers, and so on. Specialised staff may report to various levels of the organisation, such as the corporate level, the division level, or the decentralized facility level.

In their highly influential book, In Search of Excellence (1982), Thomas Peters and Robert Waterman identified 8 major attributes of an excellently managed company.

These two authors have discovered that those companies known for their excellence tend to have relatively few staff personnel at corporate headquarters. Consequently they are highly decentralized. Such high degree of decentralisation is based on the integrity of the various divisions or units.

In such companies product development, usually a corporate or group activity, is wholly decentralized at the division level and do not even involve corporate planners at the corporate level.

Line, Staff and Functional Authority:

At this stage we have to bring into focus an important issue — the distinction among different types of authority. In an organisation different types of authority are created by the relationships among individuals and among departments.

There are three types of authority:

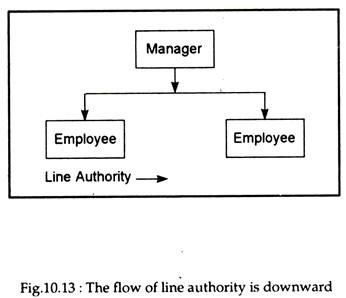

Line Authority:

Line authority defines the relationships between superior and subordinate, i.e., the authority that managers exercise over their immediate subordinates. It is a direct supervisory relationship. Managers who supervise operating employees or other managers have line authority.

It is command authority and corresponds directly to the chain of command. It flows downward through the organisational levels directly from a superior to his subordinates, as Fig. 10.13 shows.

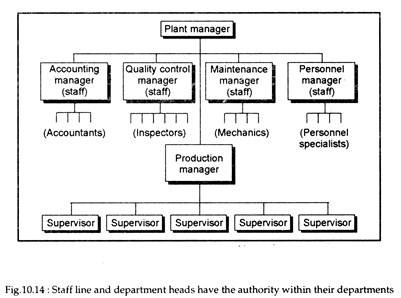

This type of authority is more clearly illustrated in Fig.10.14. It shows that both line and staff department managers exercise line authority over their immediate subordinates.

In truth, all practising managers exercise line authority over their employees.

Staff Authority:

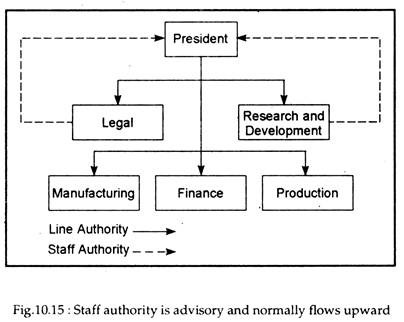

Staff authority is advisory in nature. The role of some managers is to provide advice or technical assistance. They are granted advisory authority. Such authority is the right possessed by staff units or specialists to advice, recommend, or counsel line personnel.

It does not provide any basis for direct control over the subordinates or activities of other departments with whom they consult, as Fig.10.15 shows. It is clear that within the staff manager’s own department, he (she) exercises line authority over the subordinates of the department.

In short, staff authority does not give the staff members the authority to dictate to the line or command them to take certain actions. It is, in fact, most frequently directed upward, toward those above the staff members.

It is important to note that this is the most common type of staff relationship with line departments and is dependent on the degree of influence of the staff.

Functional Authority:

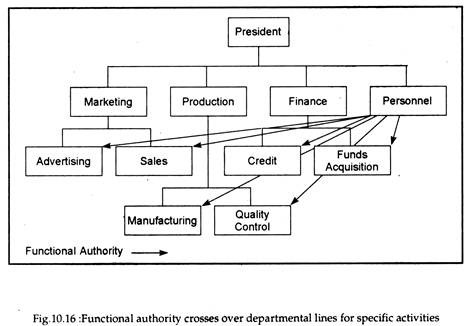

Perhaps the strongest relationship that staff can have with line units is functional authority. It is authority delegated to an individual or department over specific activities undertaken by personnel in other departments. Staff departments may be assigned such authority to control their systems’ procedures in other departments.

For example, the personnel department may give functional authority to monitor and receive compliance in operating departments for recruitment, selection and performance appraisal systems. See Fig.10.16.

When granted functional authority by top management, a staff specialist has the right to command line units in those matters regarding functional activity in which the staff specialies.

There are other examples of different staff specialists exercising functional authority. Cost accounting departments, for instance, usually can require certain reports at a certain time from line managers.

Likewise, the production scheduling department may be given the production to determine which jobs the departments are to do and the priorities of those jobs. Or, the quality control inspector may be given sufficient authority to require production departments to complete satisfactorily a production run that may not meet required standards.

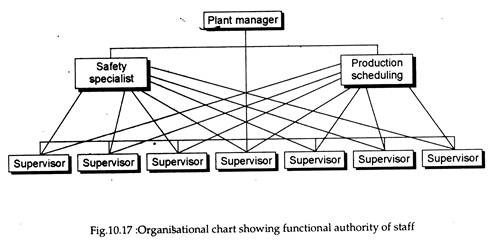

An important implication of functional authority is that when such authority is granted to staff units, the principle of unity of command is violated. As a result various organisational conflicts arise. This point is illustrated in Fig.10.17.

Furthermore, the excess use of functional authority may undermine the integrity of the line departments which are ultimately accountable for results. This explains why functional authority that is granted to staff is to be exercised only in crucial matters.

Line-Staff Conflict:

There is often conflict between and among line and staff departments and personnel. Management must be aware of some real dangers inherent in line-staff interaction.

The major causes of line-staff conflict are the following:

1. Demographic Factors:

Staff managers are usually younger than line managers, better educated, more ambitious, better dressed and more firmly allied with their profession than with their company. These demographic factors are a possible source of conflict.

2. Threats of Authority:

Line may also perceive staff managers as threats to their own authority, more so when staff managers are given functional authority. As a means of forestalling the possible erosion of their own authority, line managers may decide not to take advantage of staff expertise. Staff managers, in turn, complain that they are not being used effectively.

3. Dependence on Knowledge:

Line managers may become uncomfortable and frustrated when they become too much dependent on staff expertise and knowledge. The line managers may feel less important and deny the fact that they need the staff managers if they are to do their own jobs properly. When the knowledge (and vocabulary) group is so wide that distrust results, it is simply because the line manager does not really understand what is going on.

4. A generation gap:

A generation gap is often created in most progressive organisations inasmuch as most staff people are younger and more highly educated than line employees.

5. Staff personnel:

Staff personnel may exceed or overuse their authority and seek to give orders directly to line personnel.

6. Staff specialists:

There is often a feeling among line personnel that staff specialists do not fully understand line problems and hence this advice is not workable.

7. Credit:

There is a tendency among staff to take credit for ideas implemented by line. On the contrary, line may be reluctant to acknowledge the role staff has played in helping it resolve problems.

8. Using technical terms:

Since staff is highly specialised, it may deliberately use certain technical terms and a certain language which line cannot understand.

9. Relationship:

Top management often fails to clearly communicate the extent of authority staff has in its relationship with line.

10. Organisation hierarchy:

Finally, staff departments are usually placed in relatively high positions close to upper management in the organisational hierarchy. This is often resented by lower level line departments.

11. Other causes:

Other causes of line-staff conflict arise due to different perceptions. Line managers often see staff managers as over-stepping their authority, embracing too narrow or idealistic a perspective, or taking credit for the line managers’ accomplishments staff managers, in their turn, accuse line managers of not giving them enough authority and resisting change (in the form of new ideas).