After reading this article you will learn about:- 1. Meaning of Performance Appraisal 2. Factors in Successful Appraisals 3. Types of Appraisal Systems 4. Methods of Appraisal 5. Rating Methods 6. Reward Systems.

Contents:

- Meaning of Performance Appraisal

- Factors in Successful Appraisals

- Types of Appraisal Systems

- Methods of Performance Appraisal

- Methods to Rate Performance of Employees

- Reward Systems

1. Meaning of Performance Appraisal:

After receiving training and doing a job for quite some time, an organisation starts conducting a performance periodically; appraisal interviews are general held once or twice a year. It is preferable to separate performance appraisal interviews and career development interviews whenever possible.

As Griffin has commented:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

“When employees are trained and settled into their jobs there are many reasons to evaluate employee performance regularly. One reason is human resource research, such as validating selection devices or assessing the impact of training programmes. A second reason is administration- to aid in making decision about pay raises, promotions and training. And another reason is to provide feedback to employees to help them improve their present performance and plan future careers.”

Performance appraisal is a formal, structured system designed to measure the actual job performance of an employee compared to the following four clear-cut objectives:

1. Developing individual plans for improvement based on agreed upon goals, strengths and weaknesses.

2. Identifying growth opportunities.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

3. Documenting present job performance to provide superiors with information to make decisions on salary, promotion, demotion, transfer and termination.

4. Providing the opportunity for formal feedback.

Organisations normally require managers to conduct formal performance appraisal sessions annually or semi-annually. The basic purpose is documentation and planning.

A related point may also be noted in this context. Since performance evaluations often help determine wages and promotions, they must be fair and non-discriminatory — that is, valid.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

As Griffin has pointed out:

“In the case of appraisals, content validation is used to show that the appraisal system accurately measures performance on important job elements and does not measure traits or behaviour that are irrelevant to job performance”.

2. Factors in Successful Appraisals:

The success of performance appraisal largely depends on two factors — the parties involved and the system used.

The manager and the subordinates must be very clear about the purposes of a performance appraisal and they must have sufficient faith in the process and the instruments (vehicles) it uses. Each part must take necessary time to prepare for the session.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

It is necessary for the manager to gather the results of his (her) ongoing observations, specific performance records, ideas for improvement and plans for growth and development; in addition, the manager must allow sufficient time for reflection and summation. Similar responsibilities lie on the employee.

It is essential for each side in the game to understand the appraisal system to be used and the criterion used to measure an employee performance. If a manger behaves like a dictator and holds all the cards or is formulating rules during the session, the employee is unlikely to receive a realistic appraisal of his performance. Consequently the latter will be confused, resentful and disciplined to cooperate in the endeavour.

The system has to be quite appropriate for the employee’s current job. At times a system is designed primarily for one category of employees but is used extensively for all categories of personnel. Obviously it will fail to be reflective of the performance on the other jobs.

Furthermore, the criteria to measure the employee should not only be appropriate, but also specific. Finally the criteria should be such as to enable the manager to evaluate the employee against standards, not against another employee.

3. Types of Appraisal Systems:

Performance appraisal systems have two broad components: the first part is the criterion against which an employee’s performance is measured and evaluated (e.g., quality of work, knowledge, attitude); the other is the rating scale showing what the employee is capable of achieving or performing on each criterion (good, 6 out of 10,90% etc.).

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Two basic types of Performance appraisal systems are:

Objective performance appraisal system and subjective (or judgemental) performance appraisal system. Most systems used today are variations of these. Now each system may be examined separately.

(a) Objective Performance Appraisal System:

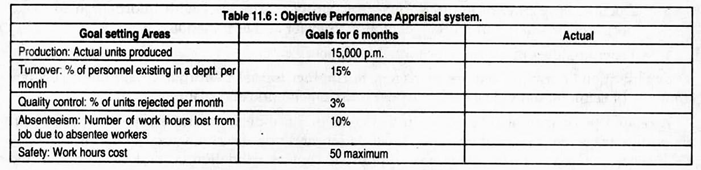

Objective methods include counts of output, scrap page rate, rupee value of sales, number of claims processed, and so on. In this system both the criteria for evaluation and the method of measurement are specific in nature, as illustrated in Table 11.6. Five specific criteria have been listed, viz., production, turnover, quality control, absenteeism and safety. There is no rating scale.

Rather it has been replaced by specific goals or objectives to be realised in performance. For instance, the production goal for 6 months is (15000 x 6) = 90,000 units.

The employee is supposed to know on what criteria the performance appraisal will be based and what the measures will be (how performance measures up to goals). In this system the goals are established bilaterally—by the employer and the manager together.

They also know what performance is based on and how it will be measured. Performance appraisal reports provide the necessary feedback. The employee is thus enabled to know his (her) position, i.e., where he (she) stands at all times.

The objective Performance appraisal system illustrated in Table 11.6 is derived from management by objectives (MBO) and appraisal by results. According to P.F. Drucker, MBO is a one-to-one approach to improving performance of both individuals and the organisation as a whole.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

It demands face-to-face meetings between managers and subordinates. Subordinates are asked to set special goals that are likely to lead to improved performance. Supervisors also set supplementary goals. Once consensus is reached about specific goals, mangers assign priorities to these and time limits are set by which they should be achieved.

Follow-up sessions are held on a periodic basis in order to review the progress achieved and the required adjustments to the goals are made.

These goals and their priorities are not rigid. Changing situations or circumstances often demand a reassignment of priorities and new goal setting. New resources have to be harnessed to accomplish the goals.

The performance of different individuals are evaluated on the basis of three rules or criteria:

(a) The number of goals they achieve,

(b) How they achieve them, and

ADVERTISEMENTS:

(c) On the basis of how their performance have improved.

The use of MBO as an appraisal system requires top management support and commitment. It usually starts in an organisation at the top and gradually filters down, on the basis of its success at the top level and a preconditioning at lower levels to gain support for it. One of the preconditions of success of the MBO system is that the people who are appraised with it must be allowed to participate in goal setting.

They require regular feedback and continuous help in measuring their progress. The manager and employee must reach agreement about standards for performance. If MBO is used appropriately it develops strong commitments to fulfill the goals. It also fosters an understanding of how one’s position and efforts are inseparably linked with those of others. Finally it gives a sense of equity to the entire appraisal process.

The whole process of application of MBO to Performance appraisal follows a clear-cut order or a logical sequence. It starts with clear and concise goal setting by top management. These strategic goals dictate various tactical goals required of departments, divisions and individual employees. Managers work together with their subordinates, in formulating these tactical goals.

Once consensus is reached about these goals, time limits are set on each to facilitate the monitoring of the individual’s progress. Throughout the appraisal period comparisons are made between ‘what is’ and ‘what ought to be’. Often revisions become necessary either in the goals or in their time limits. New goals, time limits, or tactics to achieve goals have to be fixed and mutually worked out.

(b) Subjective Performance Appraisal System:

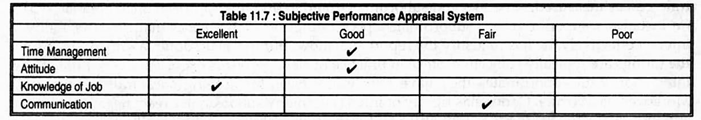

Subjective (judgemental) Performance appraisal System derives its name from the fact that under the system the appraisal makes his (her) observations from the subjective (personal) viewpoint. Table 11.7 illustrates such a system.

Here four criteria are used, viz.,

(a) Time management,

(b) Attitude,

(c) Knowledge of job and

(d) Communication.

Likewise there are four items in the rating scale—excellent, good, fair and poor.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

A common problem which is faced by the manager and the employee is that rather than leading to dialogue about performance, the system can result in each partly attempting to defend its own interpretation of performance.

As W.R. Plunkett and R.F. Attner have rightly commented:

“Because of the lack of specific criterion (described factors of performance) and of a specific rating scale (increasing or decreasing descriptors of performance), the subjective appraisal system can result in the citing of critical incidents, comparisons to other employees and judgments based on personality traits (positive and negative)”

Here both the performance criteria and the categories in the scale are described. This is no doubt better, but it is still open to interpretation.

Another type of objective measure is the special performance test, in which each employee is assessed under standardised conditions. Performance tests measure ability but do not measure the extent to which one is motivated to use that ability on a daily basis.

For example, a high ability performance may be a lazy performance except when put to test. Therefore, special performance tests must be supplemented by other appraisal methods to provide a complete picture of performance.

4. Methods of Performance Appraisal:

Thus there are two methods of performance appraisal —

ADVERTISEMENTS:

(1) Manager appraisal of the subordinate and

(2) Subordinate self-appraisal.

A third method is peer appraisal under which the employee’s peers are asked to evaluate him (her). In appraising the performance of the subordinate the manager makes use of this information.

However, this method does not find wide application. Another method is upward appraisal, i.e., the question of the effectiveness of the superior by the subordinate, using a subjective system. This method is also not used by most companies.

5. Methods to Rate Performance of Employees:

Management also makes use of various methods to rate performances.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Five such rating methods are discussed below:

(a) Traditional Trait Ratings:

The traditional method of rating employee performance is in terms of traits, such as perseverance and maturity that he (she) manifested.

The method is simple enough: the superior is just required to complete a questionnaire on which 30 or 40 items are listed and he would indicate the degree to which the subordinate manifested a particular trait in terms of a five-point or several-point scale extending from ‘not at ail’ to ‘a very significant amount’.

Defects:

Various problems are associated with the use of trait ratings. In practice it is very difficult, almost impossible, for a superior to measure such traits. Secondly, even in those situations where traits can be measured, superiors and subordinates tend to find this approach unacceptable.

When, for instance, a superior gives a subordinate a poor ratings on such traits as maturity and ability to interact effectively, he has to justify the report somehow. But this is no doubt a difficult task since the ratings are typically subjective. Since in practice most supervisors experience very little, if any, interaction with subordinates they have hardly any basis for judging such traits as maturity.

Moreover, as Martin J. Ganon has rightly pointed out:

“Many subordinates react negatively if their superior characterizes them as immature and lacking in ambition. Additionally, the relationship between performance and rewards becomes clouded; there is little classification of job duties and the atmosphere is not conducive to counselling that is focused on training and career development.”

For these and other reasons the actual Performance appraisal meeting does not become really meaningful. The superior completes the required forms as a matter of routine, so to say, and generally rates only a few subordinates as either outstanding or poor; most employees receive average ratings.

(b) Single Global Ratings:

A second but related way of evaluating an employee performance is to provide a single global rating of a subordinate. The superior does not specify aptitudes, traits, or other criteria. Instead he rates the subordinate in terms of only one item that is general in nature.

Typically the superior rates the subordinate on a five-point scale extending from excellent to poor or an item such as- “In terms of all of the subordinates that have worked for you in the past five years, how would you rate his employee.”

Defects:

Most of the problems associated with traditional trait ratings are also to be found in single global ratings. The employees whose ratings are below average often react defensively; the climate of the appraisal meeting fails to encourage the manager to provide counselling and development information or to clarify the nature of the job and the relationship between performance and rewards becomes quite unclear.

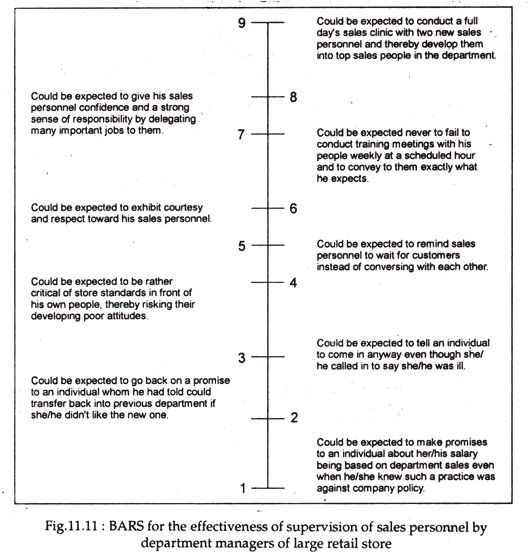

(c) Behaviourally Anchored Rating Scale (BARS):

One of the major defects of the previous two ratings systems is that they are not directly related to the job itself and thus fail to clarify its requirements so as to enable the employee to improve specific aspects of his (her) performance. To overcome this problem there is need to directly tie rating scales to the requirements of the job; that is, the scale has to reflect actual instances of ineffective and effective behaviour.

Such a scale is called a behaviourally anchored rating scale.

Such a nine-point scale for measuring the dimension of handling complaints of customers and making adjustments among sales people in a department store is given below. Such a scale was first developed in USA by Marvin Dunnette and his associates in 1968. See Fig.11.11.

This type of scale is undoubtedly superior to trait and global ratings. It is easy to make subordinates accept criticism more easily if it is tied to actual work behaviour or job performance; the performance appraisal session provides feedback that can be used for training and career development; the nature of the job is clarified and finally, a clear performance-reward relationship emerges.

Defects:

However, the major argument often put forward against using such a scale is that its construction is not that easy.

As Gannon has commented:

“The researcher typically observes workers performing the job and develops a series of descriptions characterizing effective and ineffective performances. He then meets with the workers and shows them an early version of the scale. Their criticisms and suggestions are subsequently used as the researcher ^attempts to refine the scale. This process may take several months and several meetings before it is finalized.”

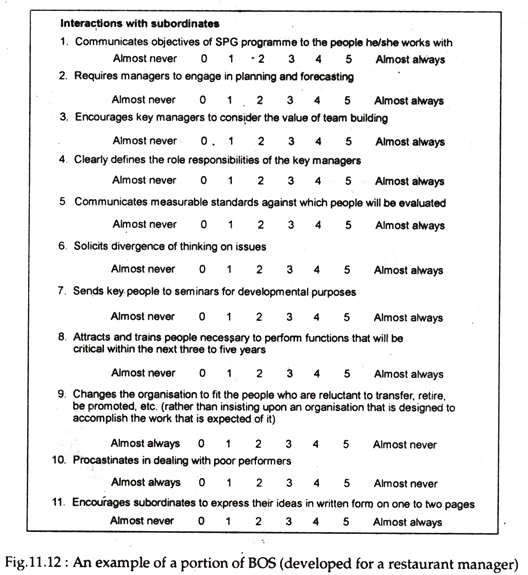

(d) Behavioural Observation Scales (BOS):

It attempts to combine trait rating (or check list) and BARS. Managers and employees are asked to develop an exhaustive list of factors and traits that are important if a job has to be successfully accomplished. Fig.11.12 shows the rater had to do only one thing.

He needs to indicate how frequently the rates of subordinates exhibited the trait or factor in terms of a five-point or several-point scale extending from ‘almost never’ to ‘almost always’.

Merit and Defect:

The only advantages of BOS is that they provide rich data for performance feedback and counselling. But their main defect is that the raterers perception of the frequency with which a subordinate exhibits a specific trait or factor is likely to be distorted and incorrect, especially if the rater is not continuously working with the subordinate.

(e) Goal-Oriented Appraisal:

So far we have treated the performance appraisal process as one way: the superior tells the employee how his traits or behaviour deviate from expectations, even in the highly motivated employee, since he is not allowed to participate in defining her own goals and job.

Management by objectives (MBO) is one organisation-wide planning technique that requires employee participation in setting organisational goals. Goal-setting theory also indicates that individuals will tend to reach hard but attainable goals if such goals are accepted. For both techniques, the setting of goals can be implemented in the performance appraisal session as a method for evaluating employees.

When this method is used, the performance of a subordinate is evaluated in terms of her accomplishment of specific objectives. The subordinate participates in setting these objectives and in developing a time frame in which they are to be accomplished, hence, the discussion between the superior and subordinates tends to be objective, unemotional and helpful.

This approach is frequently treated favourably both by superiors and subordinates, since it focuses only on the attainment of specific goals. Ideally, the employee sees a relationship between effort and performance and between appropriate performance and suitable rewards.

However, “this approach does not describe the specific behaviours that lead to success on the job. In this way it is inferior to behaviourally anchored rating scales or behavioural observation scales and goal setting should be used in appraising in most situations.”

6. Reward Systems:

Organisations and their leaders must have reward system or the ability to reward and punish organisational members if goals are to be achieved. But there are many situations in which managers are virtually powerless and do not have a sufficient number of rewards and sanctions that they can use to motivate subordinates.

In unionized firms, for instance, managers have only a limited ability to give merit salary increases.

Research has indicated that managers are less motivated by money than other rewards appealing to their higher-order needs such as the need for achievement, recognition and self-actualization. However, practices in industry suggest that money is a very important reward.

Large companies in the U.S.A. often introduce gain-sharing plans that allow the worker to participate in the profits derived from their labour input. There are several well-known plans such as the Scanion Plan and Improshare.

The concept underlying them all is defining a business unit — typically a plant or a major department and relating pay to the overall performance of the unit. Monthly bonuses are paid to all employees in a unit based on a predetermined formula, provided that productivity and profits increase.

Gain-sharing plans are a helpful antidote to many of the problems associated with individual incentive plans. Admittedly a considerable body of evidence suggests that individual piece-rate incentive systems in which each employee is paid on the basis of the number of units he manufactures are generally related to higher levels of productivity than a reward system offering only regular salaries.

However, such piece-rate systems also tend to result in increased conflict among workers and they tend to punish workers going above a predetermined level of performance, at least partly because they apprehend that management will decrease the financial incentive once it has established an average but high number of pieces of output the each worker can achieve.

Management also uses profit-sharing and employees’ stock ownership to motivate employees. However, it is difficult for employees to see a direct link between their own efforts and the rewards accruing from these incentives, especially in large organisation.

Still, these plans seek to promote a sense of identification between each individual employee and the organisation. Hence, it is desirable to combine gain-sharing with profit-sharing and employee stock ownership plans whenever it is feasible to do so.

Managers also need to invoke sanctions periodically to ensure that poor performing individuals increase their performance. These include verbal reprimands, formal and written warnings, short layoffs and termination. Some managers have become highly creative in this area.

Whatever sanctions are used, it is important for mangers to bear in mind that they should be a. last resort. Motivationally, rewards are much more strongly linked to effective performance than are sanctions, which tend to have only a short-nm effect on behaviour.

Still, sanctions are necessary in some instances and even the most extreme sanction or termination provides a warning to others that ineffective performance will not be tolerated.