In this article we will discuss about:- 1. Introduction to Disinvestment in CPSEs 2. Phases of Disinvestment in CPSEs 3. Classification 4. Department 5. Policies 6. Understanding the Strategic Sale Agreements 7. The Current Policy 8. Advantages of Listing 9. Future Strategy.

Contents:

- Introduction to Disinvestment in CPSEs

- Phases of Disinvestment in CPSEs

- Classification of Disinvestment in CPSEs

- Department for Disinvestment in CPSEs

- Policies for Disinvestment in CPSEs

- Understanding the Strategic Sale Agreements

- The Current Policy of Disinvestment in CPSEs

- Advantages of Listing

- Future Strategy for Disinvestment in CPSEs

1. Introduction to Disinvestment in CPSEs:

The Public Enterprises have played a vital role in the development of India’s economy. The nature and role of these enterprises was conceived at a time when the technological landscape and the national and international economic environment were very different. Today, the private sector in India has come of age and it substantially contributes to the nation-building process.

In the scenario, both the public sector and private sector are mutually complementary parts of the national sector. Hence, there arose a need to assess and change the role of public sector in a highly competitive market. The intense pressure on public finances also compelled the Centre as well as State Governments to embark on a programme of disinvestment.

The policy on ‘Disinvestment in CPSEs’, i.e. disinvestment of government equity in CPSEs began in 1991-92. The policy of the government on disinvestment gradually evolved since then can be divided into two phases. The period until 1997-98 is generally considered the initial phase while the period starting from 1998-99 is considered the second phase of disinvestment.

From 1991-92 to 1996-97, disinvestment in CPSEs was handled by the Department of Public Enterprises. Subsequently, the Department of Economic Affairs, Ministry of Finance took over the task of disinvestment in CPSEs.

2. Phases of Disinvestment in CPSEs:

The policy, as enunciated in the interim Budget 1991-92 presented by the Chandrasekhar Government, was to disinvest up to 20 per cent of the government equity in selected PSEs, in favour of mutual funds and financial or investment institutions in the public sector. The objective of the policy was stated to be to broad base the equity, improve management and enhance the availability of resources for the PSEs. The disinvestment was expected to yield Rs.2500 crores to the exchequer in 1991-92.

The Second Phase:

In its first budgetary pronouncement, the new National Democratic Alliance Government in 1998-99 decided to bring down government shareholding in the PSUs to 26 per cent in the generality of cases, thus facilitating ownership changes, as was recommended by the Disinvestment Commission. It however, stated that the government would retain majority holdings in PSEs involving strategic considerations and that the interests of the workers would be protected in all cases.

Subsequently, the government announced that its strategy for 1999-2000 towards public sector enterprises will continue to encompass a judicious mix of strengthening strategic PSUs, privatizing non-strategic PSUs through gradual disinvestment or strategic sale and devising viable rehabilitation strategies for weak units. A highlight of the policy was that the expression ‘privatisation’ was used for the first time.

3. Classification of Disinvestment in CPSEs:

Strategic and Non-Strategic Classification:

On 16 March 1999, the government classified the Public Sector Enterprises into strategic and non-strategic areas for the purpose of disinvestment.

It was decided that the Strategic Public Sector Enterprises would be those in the areas of:

1. Arms and ammunitions and the allied items of defence equipment, defence aircraft and warships;

2. Atomic energy (except in the areas related to the generation of nuclear power and applications of radiation and radio-isotopes to agriculture medicine and non- strategic industries); and

3. Railway transport.

All other Public Sector Enterprises were to be considered non-strategic. For the non-strategic Public Sector Enterprises, it was decided that the reduction of government stake to 26 per cent would not be automatic and the manner and pace of doing so would be worked out on a case-to-case basis.

Further, any decision in regard to the percentage of disinvestment, i.e. government stake going down to less than 51 per cent or to 26 per cent, would be taken on the basis of- (i) Whether the industrial sector requires the presence of the public sector as a countervailing force to prevent concentration of power in private hands, and (ii) Whether the industrial sector requires a proper regulatory mechanism to protect the consumer interests before Public Sector Enterprises are privatised.

4. Department for Disinvestment

in CPSEs:

The government also established a new Department for Disinvestment under the Ministry of finance on 10 December 1999 to introduce a systematic policy approach to disinvestment and privatisation and to give a fresh impetus to the strategic sales of identified PSUs.

The Department of Disinvestment was given the following functions:

(a) (i) All matters relating to disinvestment of Central Government equity in CPSEs; (ii) All matters relating to sale of Central Government equity through offer for sale or private placement, in the erstwhile CPSEs.

(b) Decisions on the recommendations of the Disinvestment Commission on the modalities of disinvestment, including restructuring.

(c) Implementation of disinvestment decisions, including appointment of advisers, pricing of shares, and other terms and conditions of disinvestment.

(d) Matters relating to Disinvestment Commission.

(e) Issues relating to CPSEs for purposes of disinvestment of government equity only.

(f) Financial policy in regard to the utilization of the proceeds of disinvestment, channelised into the National Investment Fund.

All other post-disinvestment matters, including those relating to and arising out of the exercise of ‘call-option’ by the Strategic Partner in the erstwhile CPSEs, were to be continued to be handled by the administrative Ministry (or Department concerned), where necessary, in consultation with the Department of Disinvestment. The Department was later elevated in 2001 and became the Ministry of Disinvestment. Subsequently from 2004, it has once again been turned into a Department of the Ministry of Finance.

5. Policies for Disinvestment in CPSEs:

i. Disinvestment Policy for 2000-01:

The highlights of the policy for the year 2000-01 as enunciated in Budget speech 2000-01 were that for the first time the government made the statement that it was prepared to reduce its stake in the non-strategic PSEs even below 26 per cent if necessary, that there would be increasing emphasis on strategic sales and that the entire proceeds from disinvestment/privatisation would be deployed in social sector, restructuring of PSEs and retirement of public debt.

The main elements of the government’s clear and unambiguous policy towards the public sector were:

1. To restructure and revive potentially viable PSEs;

2. To close down PSEs which cannot be revived;

3. To bring down government equity in all non-strategic PSEs to 26 per cent or lower, if necessary;

4. To fully protect the interests of workers;

5. To put in place mechanisms to raise resources from the market against the security of PSEs’ assets for providing an adequate safety-net to workers and employees;

6. To establish a systematic policy approach to disinvestment and privatisation and to give a fresh impetus to this programme, by setting up a new Department of Disinvestment;

7. To emphasize increasingly on strategic sales of identified PSEs;

8. To use the entire receipt from disinvestment and privatisation for meeting expenditure in social sectors, restructuring of PSEs and retiring public debt.

During 1998-2000, the government approved restructuring of 20 PSUs. As a result, many PSUs were able to restructure their operations, improve productivity and achieve a turn-around in performance. In 2000, the government also approved a comprehensive package for restructuring of SAIL, a Navaratna PSU.

However, in order to secure the presence of the public sector as a countervailing force, the government on 23 June 2000 took the decision of not going for disinvestment of GAIL, IOC and ONGC, and retaining them as flagship companies.

The government found that resources under the National Renewal Fund are not sufficient to meet the cost of Voluntary Separation Scheme (VSS) for PSUs which need to be closed down as they are sick and not capable of being revived. It was also realized that if the assets of those PSUs are unbundled and realized, then they can be used for funding VSS.

In view of the situation, the government decided to put in place mechanisms to raise resources from the market against the security of these assets and use these funds to provide an adequate safety-net to workers and employees.

The government, further, affirmed that equity in all non- strategic PSUs will be reduced to 26 per cent or less while fully protecting the interests of the workers. The government added that the entire receipt from disinvestment and privatisation will be used for meeting expenditure in social sectors, restructuring of PSUs and retiring public debt.

ii. Disinvestment Policy for 2001-02:

The government’s approach to PSEs was also outlined in the address by the President to Parliament during the Budget Session, February 2001. The threefold objective was: revival of potentially viable enterprises; closing down of those PSUs that cannot be revived; and bringing down government equity in non-strategic PSUs to 26 per cent or lower.

The President added “that the interests of workers will be fully protected through attractive VRS and other measures. The government has decided to disinvest a substantial part of its equity in enterprises such as Indian Airlines, Air India, ITDC, IPCL, VSNL, CMC, BALCO, Hindustan Zinc, and Maruti Udyog. Where necessary, strategic partners would be selected through a transparent process.”

In the Budget Speech 2001-02, it was announced that the process of disinvestment was in the advanced stage in many of the PSUs. A receipt of Rs.12,000 crore was expected from disinvestment during the financial year. Out of this amount, Rs.7,000 crore was to be used for providing restructuring assistance to PSUs, safety net to workers and reduction of debt burden.

The remaining sum of Rs.5000 crore was to be used to provide additional budgetary support for the Plan primarily in the social and infrastructure sectors. This additional allocation for the Plan was to be contingent upon realisation of the anticipated receipts.

The Public Sector Disinvestment Commission was reconstituted on 24 July 2001 with Dr. R.H. Patil as Chairman (part-time) along with four other Members (part-time) and a full time Member-Secretary. The then Ministry of Disinvestment had informed the Commission on 23 January 2002 that all non- strategic CPSUs, including subsidiaries, but excluding IOC, ONGC and GAIL, stood referred to the Commission for it to prioritize, examine and make recommendations in the light of the government policies articulated earlier on 16 March 1999 and the budget speeches of Finance Ministers from time to time.

The reconstituted Commission submitted its reports on 41 CPSEs, including review cases of earlier Commission’s recommendations on 4 CPSEs. The term of the Commission expired on 31 October 2004 and the Commission was wound up.

iii. Disinvestment Policy for 2002-03:

The government decided in September 2002 that CPSEs and Central Government owned cooperative societies, where government’s ownership is 51 per cent or more, should not be permitted to participate as bidders in the disinvestment of other CPSEs as bidder unless specifically approved by the Core Group of Secretaries on Disinvestment (CGD).

In December 2002, on the basis of a proposal of the Department of Fertilizers, it was decided that Multi State Cooperative Societies under the Department of Fertilizers be allowed to participate in the disinvestment of fertilizer CPSEs including National Fertilizers Limited.

In a suo motu statement made in both Houses of Parliament on 9th December, 2002, by the then Minister of Disinvestment, the government reiterated the policy as-

The main objective of disinvestment is to put national resources and assets to optimal use and in particular to unleash the productive potential inherent in our public sector enterprises.

The policy of disinvestment specifically aims at:

1. Modernization and upgradation of Public Sector Enterprises;

2. Creation of new assets;

3. Generating of employment; and

4. Retiring of public debt.

Government would continue to ensure that disinvestment does not result in alienation of national assets, which, through the process of disinvestment, remain where they are. It would also ensure that disinvestment does not result in private monopolies. In order to provide complete visibility to the Government’s continued commitment of utilisation of disinvestment proceeds for social and infrastructure sectors, the Government would set up a Disinvestment Proceeds Fund.

This Fund would be used for financing fresh employment opportunities and investment, and for retirement of public debt. For the disinvestment of natural asset companies, the Ministry of Finance and the Ministry of Disinvestment would work out guidelines.

The Ministry of Finance would also prepare for consideration of the Cabinet Committee on Disinvestment a paper on the feasibility and modalities of setting up an Asset Management Company to hold, manage and dispose the residual holding of the Government in the companies in which the Government’s equity has been disinvested to a strategic partner.

iv. Disinvestment Policy for 2003-04:

In the budget speech for 2003-04, the government announced that details regarding the already announced Disinvestment Fund and Asset Management Company, to hold residual shares post disinvestment, would be finalized early in 2003-04. Subsequently, on 25 April 2003, the then Ministry of Disinvestment issued guidelines regarding Management-Employee Bids in Strategic Sale to encourage and facilitate the participation of employee participation in strategic sales.

The National Common Minimum Programme (NCMP) adopted by the United Progressive Alliance (UPA) Government in May 2004 outlined the policy of the government with respect to the public sector as mentioned below-

The UPA Government is committed to a strong and effective public sector whose social objectives are met by its commercial functioning. But for this, there is need for selectivity and a strategic focus. The UPA is pledged to devolve full managerial and commercial autonomy to successful, profit-making companies operating in a competitive environment. Generally profit-making companies will not be privatized.

All privatizations will be considered on a transparent and consultative case-by-case basis. The UPA will retain existing ‘navratna’ companies in the public sector while these companies raise resources from the capital market. While every effort will be made to modernize and restructure sick public sector companies and revive sick industry, chronically loss-making companies will either be sold-off, or closed, after all workers have got their legitimate dues and compensation. The UPA will induct private industry to turn around companies that have potential for revival.

The UPA Government believes that privatization should increase competition, not decrease it. It will not support the emergence of any monopoly that only restrict competition. It also believes that there must be a direct link between privatization and social needs—like, for example, the use of privatization revenues for designated social sector schemes. Public sector companies and nationalized banks will be encouraged to enter the capital market to raise resources and offer new investment avenues to retail investors.

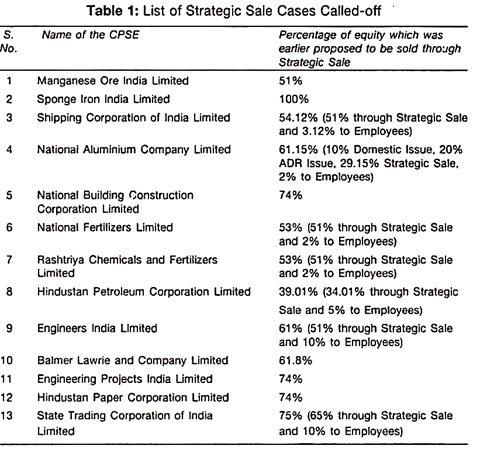

In conformity with the policy enunciated in NCMP, it was decided in February 2005 to formally call off the process of disinvestment through Strategic Sale of profit making Central Public Sector Enterprises (CPSEs), as enumerated below-

The Budget Speech 2004-05 (July 2004) said disinvestment and privatization are useful economic tools, which will be selectively employed by the government, consistent with the declared policy. Further, the government will establish a Board for Reconstruction of Public Sector Enterprises (BRPSE) to advise the government on the measures to be taken to restructure PSEs, including cases where disinvestment or closure or sale is justified. The disinvestment revenues will be part of the Consolidated Fund of India.

In January 2005, the government approved, in principle, the following:

1. Listing of currently unlisted profitable CPSEs, each with a net worth in excess of Rs.200 crore, through an Initial Public Offering (IPO) either in conjunction with a fresh equity issue by the CPSE concerned or independently by the Government on a case to case basis, subject to the residual equity of the government remaining at least 51 per cent and the government retaining management control of the CPSE;

2. Sale of minority shareholding of the government in listed and profitable CPSEs either in conjunction with a Public Issue of fresh equity by the CPSE concerned or independently by the government subject to the residual equity of the government remaining at least 51 per cent and the government retaining management control of the CPSE; and

3. Constitution of a National Investment Fund (NIF) into which the realisation from sale of minority shareholding of the government in profitable CPSUs would be channelised.

In November 2005, the government reiterated its decision, in principle, to list large, profitable CPSEs on domestic stock exchanges and to selectively sell small portions of equity in listed, profitable CPSEs other than the Navratnas.

The NIF is to be maintained outside the Consolidated Fund of India and the income from NIF would be used for two broad investment objectives:

(i) 75 per cent of annual income of NIF to be used as investment in social sector projects which promote education, health care and employment; and

(ii) The rest 25 per cent of annual income to be used to meet the capital investment in selected profitable and revivable Public Sector Enterprises that yield adequate returns in order to enlarge their capital base to finance expansion/diversification.

The corpus of the National Investment Fund is to be of a permanent nature. The Fund is to be professionally managed to provide sustainable returns to the government, without depleting the corpus. Select public sector Mutual Funds have been entrusted with the management of the corpus of the Fund.

Fund Managers:

The following Public Sector Mutual Funds have been appointed (initially) as Fund Managers to manage the funds of NIF under the ‘discretionary mode’ of Portfolio Management Scheme which is governed by SEBI guidelines, namely- (i) the UTI Assets Management Company Ltd. (ii) the SBI Funds Management Company (Pvt.) Ltd., and (iii) the Jeevan Bima Sahayog, Asset Management Company Ltd.

Corpus of NIF:

The corpus of the Fund through the proceeds from the disinvestment in Power Grid Corporation of India Limited and Rural Electrification Corporation stood at Rs.1814.45 crore. While the pay out on NIF, in the first year, stood at Rs.84.81 crores, it was Rs.206.21 crores in the second year. (Average income worked out to 8.47 per cent in the first year and 10.02 per cent in the second year). The average income for the two years, therefore, worked out to 9.245 per cent, against the hurdle rate of 9.25 per cent.

Notable Disinvestment in CPSEs under UPA Government:

Several notable disinvestments were made in CPSEs during the first term of Prime Minister Manmohan Singh. The government approved disinvestment of 5.25 per cent equity of National Thermal Power Corporation Limited (NTPC) on 12th July, 2004 out of government’s shareholding in conjunction with the IPO by the Company. The IPO that was completed in October 2004 fetched an amount of Rs.2684.07 crore.

Subsequently on 25th November, 2005, the government decided, in principle, to list large, profitable CPSUs on domestic stock exchanges and to selectively sell small portions of equity in listed, profitable CPSUs, other than the Navratna CPSEs. The government sold 8 per cent equity in Maruti Udyog Limited (MUL) in January 2006 out of its residual shareholding of 18.28 per cent to public sector financial institutions (FIs) and public sector banks through a differential pricing method.

The government realized, in the process, Rs.1567.60 crore from this sale. Subsequently in March 2006, 0.01 per cent equity of the Company was sold to the employees and the government realized an amount of Rs.2.08 crore. On 21 December 2006, the government decided to disinvest its entire residual shareholding of 10.27 per cent in Maruti Udyog Limited.

The shareholding of 10.27 per cent was finally disinvested in May 2007 through the differential pricing method to Indian public sector FIs, public sector banks and Indian Mutual Funds. The government realized in the process Rs.2277.62 crore from this disinvestment.

In February, 2007, the government decided to piggy-back with an ‘Offer-for-Sale’ of 10 per cent, 5 per cent and 5 per cent of the pre-issue paid-up capital of REC, PGCIL and NHPC respectively. The IPO of PGCIL was completed in October 2007 and the government realized an amount of Rs.994.82 crore. The IPO of REC was completed in March 2008 and the government realized an amount of Rs.819.63 crore. The IPO of NHPC was completed in August 2009 and the government realized an amount of Rs.2012.85 crore.

In August 2007, the government approved disinvestment of 10 per cent equity in Oil India Ltd, out of its shareholding along with fresh issue of equity of 11 per cent of the post-issue paid- up capital of Oil India Limited and simultaneous disinvestment of 10 per cent equity of government in favour of IOC, HPCL and BPCL in the ratio of 2:1:1, at the market discovered price. The IPO was completed in September 2009 and the government realized an amount of Rs.2247.046 crore.

Starting from 1991-92 when the government began disinvesting till 30 September 2009, the total receipts have been to the tune of Rs.57,682.93 crore. Out of this, the majority receipts of Rs.39,617.91 have been through sale of minority shareholding.

Receipts from sale of residual shareholding in disinvested CPSEs/companies has been Rs.6,398.27 crore while receipts through Strategic Sale has been Rs.6,344.35 crore. Other earnings have been through receipts from other related transactions (Rs.4005.17 crore) and receipts through sale of majority shareholding of one CPSE to another CPSE (Rs.1,317.23 crore).

6. Understanding the Strategic Sale Agreements

:

In the strategic sale of a company, the transaction has two elements- transfer of a block of shares to a Strategic Partner, and transfer of management control to the Strategic Partner. The transfer of shares by government may not necessarily be such that more than 51 per cent of the total equity goes to the Strategic Partner for the transfer of management to take place. In the case of PSEs, in order that the company no longer has the character of a government company, the transfer of shares involves bringing down governments shareholding below 51 per cent.

As per the Companies Act, 1956 a ‘Government Company’ is a company in which the government holds more that 51%. The Act does not define what a PSE is. Once the governments’ shareholding goes below 51 per cent, it ceases to be a government company and hence, it requires changes in the Articles of Association of the company especially in relation to the Presidential directives, etc.

The Strategic Partner, after the transaction, may hold less percentage of shares than the government but the control of management would be with him. For instance, if in a PSU the shareholding of government is 51 per cent and the balance is dispersed in public holdings, then government may go in for a 25 per cent strategic sale and pass on management control, though the government would post-transfer have a larger share holding (26%) than the Strategic Partner (25%).

In Company Law, the number 26 per cent has a special significance because at least three-fourths majority is required in a general meeting to get a special resolution passed, and the 26 per cent block acts as a check. Special resolutions are required under law in case of certain critical decisions by the company such as reduction of capital, alteration in Articles of Association and Memorandum of Association, winding up of the company, issue of share with variation of rights of special classes of shareholders, etc.

However, in case of strategic sale of PSEs, government typically has affirmative rights on several issues, which are much wider in scope than what is provided in Company Law for special resolutions. In fact, the Agreements can be structured such that these rights are exercisable even when government holding goes below 26 per cent. The other critical number in Company Law is 10 per cent shareholding because below it one loses voting rights unless specially provided.

The Strategic Sale agreements assume great significance in the case of strategic sale of PSEs since the shareholders mutually agree to certain rights and obligations which may by dint of the Agreement between the parties assign certain special rights and obligations on the shareholders to which they would normally not be bound through the provisions of the Company Law.

However, the government has to ensure that the Agreements signed with the Strategic Partner adequately safeguard the governments/nation’s interests, the interests of the company and finally those of the employees. Therefore, these documents have to be carefully structured.

In a strategic sale the various stakeholders involved in the transaction are the PSE itself, the Government of India, Strategic Partner, Employees, Other Shareholders, Company Law, SEBI, and Environment issue. While the government and the Strategic Partner are the obvious stakeholders, the transaction affects the other shareholders and the employees. The shareholders are directly affected as the value of the shared held by them depends on the success of the transaction.

Transfer of shares is generally governed by the provisions of the Companies Act, 1956. In case of listed companies, however, the interest of the small investors is taken care of by SEBI through its various regulations. The SEBI Takeover Code gets triggered when a person acquires more than 15 per cent of the voting equity shares of the company.

Then, the person taking over these shares is required to make a public offer to purchase shares not less than 20 per cent of the equity of the company. This provision has a great impact on the strategic sale transaction as the transaction size more than doubles, which in big PSEs may mean enormous sums of money.

When the deal size goes up, it reduces the number of players and hence competition. The other impact it can have is that it reduces the floating stock, which can at times go even below 10 per cent, resulting in de-listing of the company. Reduction in floating stock affects trading and hence impacts the value of the residual shareholding of the government.

Apart from the immediate effect the transaction would have on the share prices, the other shareholders also get affected depending upon whether the Strategic Partner enhances corporate value and hence their earnings or not.

The employees also equally as from the security of the public sector work environment they would find themselves in a new atmosphere of increased competition, demand for higher productivity and accountability. They would, therefore, logically try not to let go the protections presently enjoyed by them, government, in a welfare state, also would like to look after the employees’ interest.

There obviously has to be a trade-off, however, between the protection that the employees can be given and providing to the Strategic Partner a degree of freedom to run the company. These competing interests have to be carefully balanced in drafting the Agreements.

The PSU is an important player that gets affected by the transaction as when it is passed on to the hands of a serious Strategic Partner, its worth goes up. But the reverse could also happen.

The Strategic Partner, perhaps, has the highest stakes because in case the deal does not work out right he loses money and reputation in the market. On the other hand, in case the assessment made by the strategic partner about the potential of the company, its assets/liabilities position and his ability to implement a good business plan is right, he gains money, reputation and goodwill.

Typically, industries would have environmental issues, especially for manufacturing units. They may not be very relevant, however, in Consultancy Companies or Software Companies. Therefore, the Agreements have to, at times; address the environmental issues clearly, e.g. which party takes what part of the risk in regard to responsibilities for actions taken/not taken prior to disinvestment.

All these would govern the structure of the Agreements. These concerns of the various stakeholders are taken care of through the transaction documents such as Shareholders Agreement, Share Purchase Agreement, and Parent Guarantee Agreement, etc.

The shareholders agreement defines the relationship between the Strategic Partner and the government (the shareholders) once the company is transferred to the Strategic Partner.

Broadly, it addresses issues such as:

a. Exit Mechanism:

When a company is being taken over by a Strategic Partner, both the Strategic Partner and the government would like to know upfront about the exit mechanisms. Normally, there is a lock-in period for the Strategic Partner before which he cannot sell whole/part of purchased shares, typically three to five years.

This is because government would not like to encourage a fly-by-night operator take over a crucial government asset. Once the bidders know that government wants a stable and serious minded partner in the business, only serious parties would come. Similarly, in case of the bidder coming through an SPV, it is important to stipulate a lock-in period (matching with the lock-in period for the company shares) for the holding of the Strategic Partner in the SPV.

Otherwise the lock in period in case of the PSU shares becomes meaningless, as the bidder can exit out of the SPV and the government may be left with an undesirable partner.

Once a party has decided to exit, the other party should have the right of first refusal. This can act against government at times because, in future, when government wants to disinvest further, no serious offers may come as those parties would be aware of the right of first refusal provision in favour of the Strategic Partner.

Right of first refusal is normally reciprocal. Usually, the Agreement would also provide for tag-along rights to the parties in case they do not exercise their right of first refusal, i.e. in case the Strategic Partner is selling its shares to a third party, the government can require that the government’s shareholding be also sold along with the Strategic Partner’s share at the same price.

For the government, there could also be a lock-in period after which it can exit from the balance holding at any time. This may be desirable in some cases where the Strategic Partner may like to have government as a partner for some time at least, during which period, using the government’s presence, some issues (licenses, land issues, etc.) involving dealings with the government can be resolved quickly.

Government would then have a ‘put’ option exercisable after a certain period of time (say 1 year). The Strategic Partner may also look for a ‘call’ option to buy out the government but this should typically get triggered after some period of time (3-5 years depending upon the PSU). The general idea is that the Strategic Partner is there to stay and, depending upon the situation, government would exit.

After sometime, the Strategic Partner should have the freedom to go it alone and buy out government because, in any case, the policy is for government to ultimately quit from the commercial venture.

b. Raising of Capital:

On takeover, the Strategic Partner would in all likelihood have to immediately inject funds into the company for capital expenditure or to meet pending revenue expenditure. This would be required in the case of sick PSUs and may even be required in profit making PSUs as well. Therefore, the government may agree to the Strategic Partner bringing in funds at the time of takeover, itself, in which case provision in the Agreement has to be made for such ‘contribution’ shares.

In other cases, the Strategic Partner may like to first take over the management and then look to raising capital. The Agreement has to clearly provide for such situations. Capital raised can be either as equity or as a loan. Equity capital can be raised through the Rights issue, IPO, or Preferential Allotment.

However, there has to be some restrictions on the Strategic Partner raising capital in the form of equity or loan as government would not be in any position to contribute to the capital requirements, any equity subscription would mean that the percentage holding of the government would be going down.

If the post transfer holding of government were 26 per cent, then this would imply that government holding would go below 26 per cent and government would lose control as vested in the special resolution provisions of the Companies Act. The one safeguard is that even if the government holding goes below 26 per cent, if the affirmative rights survive, government’s interest vis-a-vis asset stripping, employee protection, etc. remain as the government can always block such a proposal being passed in the Board meeting/general meeting.

But a situation may arise that within the first few months government’s share-holding can go below the stipulated 15 per cent/10 per cent limit beyond which the Agreement itself does not survive. Therefore, it may be necessary that there would be a period of moratorium (say 1 year) on proposals for raising capital through equity.

Or, alternatively, the agreement may provide that for the lock-in period (3/5 years) even if agreement terminates government will have affirmative vote on select items (say asset stripping, employees) as long as government has one share.

c. Affirmative Rights:

The government cannot just handover the reigns of the company to the Strategic Partner and then take no interest in the running of the company. It has to ensure that the Strategic Partner is following the Agreement both in letter and spirit. It has to make sure that the assets of the company are not being misused or quietly disposed of or that the employees are not being adversely treated or that the Strategic Partner is not taking any action detrimental to the interest of the company.

One way of ensuring this is the section on Board Representation, i.e. through its nominees the government gets the progress report from the company in each Board meeting. Another way is for the Agreement to provide for veto rights to the government in certain important matters, called Affirmative Rights of government.

These rights are included to ensure that the Strategic Partner fulfills the desired intention of the strategic sale by the government and utilize the assets in enhancing the value of the existing business and ensure growth and not misutilise or harm the assets, including the employees.

The items on which affirmative vote of the government nominee on the board would be required, may inter alia, cover asset stripping, non-changeable line of business, guarantee exposures beyond a certain limit cannot be taken, change in service condition of employees or decision for retrenchment, opening new line of business, winding up of the company, reduction of share capital/share buy-back, etc.

It would, however, depend from case to case on what items government would like to reserve this right. It should not be so restrictive as to frustrate the efforts of the Strategic Partner or be so liberal as to give an absolute license to the Strategic Partner to do whatever he likes.

d. Deadlock:

Deadlock occurs when government holds back consent in a Board meeting on any affirmative right issue. Deadlock is first tried to be resolved through mutual discussion of senior representatives of parties. If discussion fails, then government could have a ‘put’ option at higher of FMV or unit sale price (at the time of deadlock the Strategic Partner can hold more than the shares transferred at the time of strategic sale) plus interest minus dividend paid.

The logic behind providing this option is that in case of minor issues, if government thinks fit, the government can let the Strategic Partner run the Company by quitting through the ‘put’ option at a premium as a deadlock would mean that the partners are not able to carry on together and their continuing would harm the Company. If it is major issues say asset stripping, then government would not utilize this ‘put’ option and the Strategic Partner would have to live with the situation.

e. Termination:

Termination would typically take place by mutual agreement, company becoming bankrupt, or when either party owns less than x per cent (e.g. 10%/15%/25%) of the outstanding and issued voting equity share, and/or either party owns more than x per cent (75% is relevant usually) of voting shares.

In some extremely sensitive cases government can insist that the Agreement does not terminate till government holds even one share. Covenants on confidentiality, indemnity, etc., however, have to survive termination. In case government wants protection to the employees not to terminate with the Agreement then this should be taken care of also and this should be included amongst items that would survive termination.

Similarly, the affirmative rights of the government would also seize once the Agreement terminates. On the termination of the Agreement, however, the parties are not released of the liabilities accrued prior to the termination.

f. Arbitration:

Arbitration clauses are incorporated in Agreements to take care of disputes concerning interpretation of the agreement or application or rights and obligations. Generally, Indian Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996, govern arbitration.

7. The Current Policy

of Disinvestment in CPSEs:

The current policy on disinvestment emanate from the President’s Address to the Joint Session of both the Houses of Parliament (4 June 2009) where it was stated- “Our fellow citizens have every right to own part of the shares of public sector companies while the Government retains majority shareholding and control. My Government will develop a roadmap for listing and people-ownership of public sector undertakings while ensuring that Government equity does not fall below 51 per cent”.

Furthermore, in the Budget Speech delivered on 6 July 2009, it was announced that the “Public Sector Undertakings (PSUs) are the wealth of the nation, and part of this wealth should rest in the hands of the people. While retaining at least 51 per cent Government equity in our enterprises, I propose to encourage people’s participation in our disinvestment programme. Here, I must state clearly that public sector enterprises, such as, banks and insurance companies will remain in the public sector and will be given all support, including capital infusion, to grow and remain competitive”.

The Minster added that “the Department of Disinvestment, Ministry of Finance, in consultation with Ministries/Departments will accordingly identify cases for disinvestment in select CPSEs. The focus will first be on profitable CPSEs that are listed with less than 10 per cent public shareholding (and make them compliant through Follow-on Public Offerings). Profitable unlisted companies will be also listed on stock exchanges through Offer-for-Sale or through Issue of Fresh Equity by the companies or both in conjunction.”

8. Advantages of Listing:

There are inherent advantages in the listing of shares of profitable CPSEs on the stock exchanges.

Besides enhancing shareholder’s value in such CPSEs, the process bestows the following benefits on these listed companies:

(a) Higher disclosure levels bring greater transparency, liquidity and credibility to their stocks;

(b) Enhance corporate governance through induction of ‘independent directors’ on the Boards of these CPSEs, which is mandatory for listed companies;

(c) Higher levels of public scrutiny enforce ethical conduct of business in these CPSEs and thus improve corporate culture;

(d) Expectations of investors/shareholders bring pressure upon the management to perform and to unlock the true value of these enterprises;

(e) Listing enables wider shareholding of CPSE stocks, and people-ownership of CPSEs.

9. Future Strategy for Disinvestment in CPSEs:

I. Engineers India Limited (EIL):

Engineers India Limited is a Public Sector Undertaking under the Ministry of Petroleum and Natural Gas is engaged in providing engineering and related technical services for petroleum refineries and other industrial projects. Government of India is holding 90.40 per cent paid up equity capital of the company and the balance is held by the general public. The shares of the company are listed on the stock exchanges with less than 10 per cent mandatory public shareholding.

The Cabinet Committee on Economic Affairs (CCEA) on 14 January 2010 decided to disinvest 10 per cent paid up equity capital of Engineers India Limited, out of government’s shareholding of 90.40 per cent, in the domestic market through Public Offering. After this disinvestment government shareholding in the company would come down to 80.40 per cent.

It has also been decided that before the Public Offering the company will take the following steps:

(a) Issue bonus two shares for every one share;

(b) Split one share of the face value of Rs.10 into two at the face value of Rs.5 each; and

(c) Declare special dividend of 1000 per cent of the paid up equity capital.

II. Steel Authority of India Ltd. (SAIL):

The CCEA on 8 April 2010 approved the proposal for raising additional equity by the Steel Authority of India Ltd. (SAIL) to the extent of 10 per cent of the paid up equity and disinvestment of a portion of Government of India’s shareholding in SAIL by an extent of 10 per cent through offer for sale, to be carried out in two separate tranches.

The further public offering (FPO) would comprise the first tranche of the fresh issue of 5 per cent pre-issue paid up equity of the company and offer for sale of 5 per cent of government equity in SAIL. The CCEA has accorded permission for affecting the first tranche and the second tranche, similar to the first, would be issued at an appropriate time depending on prevailing market conditions.

The further offerings along with disinvestment would be carried out as per SEBI regulations and procedure adopted by the Department of Disinvestment which is the nodal agency for handling of disinvestment of government public sector units.

As a result of the further public offer, there would be enhanced public holding in SAIL from the present level of 14.2 per cent to 31 per cent and it is expected that the enhanced holding would lead to greater public accountability leading to greater depth in the market. As a result of the secondary offering and equity dilution, there would thus be larger public ownership of the company, leading to greater public oversight and increased accountability.

The disinvestment of government’s equity in SAIL is in line with the overall policy of the government that ownership of CPSEs would be shared with the public. The proceeds from fresh issue of equity by SAIL would help in filling the resource gap in availability for funding SAIL’s capital expenditure emerging from the increased pressure on steel prices and diminished margins.

SAIL is presently amidst massive expansion plans for increasing its installed hot metal production capacity from existing 13.82 million tonnes per annum (MTPA) to 23.46 MTPA in the current phase.

III. Hindustan Copper Limited (HCL):

The paid up equity capital of Hindustan Copper Limited (HCL) is Rs.462.61 crore. Government of India is holding 99.59 per cent paid up equity capital of the Company at present. The face value of the share is Rs.5 each. The CCEA on 15 June 2010 approved the proposal for disinvestment of 10 per cent paid up equity capital of HCL out of Government of India’s shareholding along with issue of fresh equity of equal size by the Company in the domestic market.

The divestment will be done in the following manner:

(i) Issue of fresh equity by HCL to the extent of 10 per cent of the pre-issue paid up capital of the company equivalent to 9,25,21,800 shares of face value of Rs.5 each in the domestic market as per SEBI rules and regulation.

(ii) In conjunction with the issue of fresh equity as at (i) above; government to disinvest its 10 per cent of pre issue paid up capital of the company, equivalent to 9,25,21,800 shares of face value of Rs.5 each.

(iii) Reservation of shares for employees of HCL will be on a discount of 5 per cent, which will also be available to retail investors as per the guidelines of SEBI.

IV. Coal India Limited (CIL):

Coal India Ltd. (CIL), a Central Public Sector Enterprise, is a Navratna Company engaged in production and marketing of coal and coal products. At present, the paid up equity capital of the company is Rs.6316.36 crore and the Government of India holds 100 per cent of the equity in the company.

The CCEA on 15 June 2010 gave its approval to divest 10 per cent equity of the CIL out of its holding of 100 per cent through book building process in the domestic market. One per cent of the equity will be offered to the employees of CIL and its eight subsidiaries. The CCEA has also decided to allow 5 per cent price concession to the retail investors in order to encourage greater public ownership of the public sector companies.

The CCEA also approved a 5 per cent concession to the employees of the company and its subsidiaries to encourage their becoming stakeholders in the company. After this disinvestment, Government of India’s shareholding in the company would come down to 90 per cent.

V. Power Grid Corporation of India Limited (PGCIL):

Power Grid Corporation of India Limited (PGCIL) went for a maiden Initial Public Offering (IPO) of equity shares consisting of issue of fresh equity shares with 10 per cent of paid up capital and disinvestment of Government of India equity holding of 5 per cent of paid up capital in October 2007 through the book building process and the issue was subscribed 64.50 times.

The shares of the PGCIL got listed in the National Stock Exchange and Bombay Stock Exchange on 5.10.2007. PGCIL raised Rs.2984 crore at the issue price of Rs.52/- per share out of which Rs.995 crore was paid to the Government of India towards the disinvestment proceeds and the balance amount, after meeting the issue expenses, was utilized for capital expenditure of identified projects during the financial year 2007-08 and 2008-09.

The CCEA on 22 July 2010 approved the Follow-on Public Offer (FPO) of PGCIL of 84,17,68,246 Equity shares of each constituting 20 per cent of existing paid-up capital. This comprises fresh issue of 42,08,84,123 Equity Shares (10 % of existing paid-up capital) and offer for Sale (Disinvestment) of 42,08,84,123 Equity Shares (10% of existing paid-up capital).

Additional resources generated through the issue of an FPO will be utilized by PGCIL in its investment programmes. PGCIL will be required to approach the capital market for raising funds through issue of fresh equity for funding its investment programme commencing from Financial Year 2010-11.

The requirement of funds to be raised through issue of fresh equity for funding the capital expenditure for the balance Eleventh Plan period will be in the order of Rs.4200 crore. The fresh issue of FPO would result in the PGCIL meeting with the CERC allowed norms of 30 per cent equity contributions during the Eleventh Plan period.

VI. Manganese ORE (India) Ltd. (MOIL):

At present, the Central Government holds 81.57 per cent of the equity of Manganese Ore India Ltd. (MOIL), a Miniratna Central Public Sector Enterprise. The balance is held by the State Governments of Maharashtra and Madhya Pradesh to the extent of 9.62 per cent and 8.81 per cent respectively. MOIL is engaged in production of manganese ore, which is the raw material for manufacturing of alloys, an essential input for steel making and dioxide ore for manufacturing dry batteries.

The CCEA on 9 September 2010 approved the disinvestment of 10 per cent of total paid up equity of MOIL out of its holding through Initial Public Offering (IPO). The State Governments of Maharashtra and Madhya Pradesh have also decided to divest 5 per cent each of total paid up equity in MOIL out of their shareholding along with the Government of India.

This will lead to MOIL listing its shares in the Stock Exchanges. The CCEA has also approved to allow 5 per cent price discount to the employees of the company under employees reservation quota to encourage their becoming stakeholders in the company. The CCEA has further decided to allow this 5 per cent price discount to retail investors as well as to encourage the development of people-ownership.

India’s recent history of big public sector offers, both initial public offerings (IPOs) like CIL’s and follow-on public offerings (FPOs) like SAIL’s, has involved the significant participation of another government organization, the Life Insurance Corporation of India (LIC). Both in case of NMDC FPO and NTPC IPO, LIC saved the day, as high net-worth individuals (HNIs) and retail investors bid for only about a fifth of their allotments, while the interest of foreign institutional investors (FIIs) was nominal.

In such a scenario, the question arises whether such an exercise can be truly called disinvestment. No doubt, the government achieves its objective of getting the money, but it is doubtful whether there has been any price discovery or whether the ownership has become wider. In any case, it is not in anybody’s interest to have such a large holding in one entity.

The question also arises whether there was any need to have an FPO because the government can just place the shares with LIC, which can then gradually offload the shares into the market. If the response to disinvestment is poor and issues list below their offer price, investors will keep shying away.

Traditionally, some degree of underpricing has been the norm in many countries. The retail investor prefers to stay out unless convinced of a significant underpricing. On the other hand, for the government, underpricing and equity offer will be tantamount to transferring taxpayers’ wealth to investors who constitute less than 5 per cent of the population.

Since the proportion or retail investors vis-a-vis institutions is already quite high in India compared to the US, the government can afford to stop worrying about retail investors. Instead, it can be aggressive in pricing public offers. Also, there are vested interests in overpricing.

Promoters set a fund-raising target with an objective to dilute as little of the stake as possible. Merchant bankers set an unofficial price-per-share target with the promoters. The bankers too prefer a higher price as they often forgo fees. Also, reputation and size count while tallying public sector IPOs in end-of-year rankings. So, the bigger the issue, the better, which leads to a bias toward higher pricing.

In the meantime, the Securities and Exchange Board of India (SEBI) has tweaked the rules, confusing the situation. While it suggested the French auction system for the NTPC issue, it went back to the traditional book-building route for NMDC issue. SEBI has also mandated that qualified institutional buyers, which include foreign institutional investors, will have to put 100 per cent of the bid amount on application instead of the 10 per cent at present. While this is yet to take effect, it is feared that liquidity problems may temper the response to IPOs.

Disinvestment remains one of the trump cards for the government in managing fiscal deficit. However, the ambiguity over the pace of disinvestment and the absence of any visible progress in disinvestment has led to uncertainty over willingness of the government to play the disinvestment card.

However, the recent announcement that all profitable listed PSEs to have minimum 10 per cent public ownership gives the much needed traction to the disinvestment programme. The expected public offers for SAIL and CIL will determine the success of the Indian Government’s efforts to raise billions of dollars through disinvestment.

Unlike Brazil and China, where the government budget does not hang in the balance, in India, the Finance Minister is using disinvestment to balance his books. He has received a pat on the back from Standard &C Poor’s, which has raised its outlook for India to stable. But that outlook could easily be reversed if the disinvestment plans and the fiscal deficit do not meet targets.

As India is moving from a $1 trillion economy to a $2 trillion one, it has appetite to absorb these massive investments mainly due to the 38 per cent savings rate. PSE divestment has created value for investors in the long run. Taking this into consideration, several mutual funds have launched PSU Funds which would tend to benefit from the PSU divestments.