After reading this article you will learn about the kinds of risks and measures for handling of risks.

Kinds of Risk:

There are four broad categories, however many trading risks may belong to more than one of these categories;

(a) Natural risk.

(b) Human risk.

(c) Market risk.

(d) Country risk.

The Natural Risk created by natural phenomenon is usually beyond our control. Damage caused by rain, snow, floods, storms, earthquakes, lightning, pests and extreme heat or cold are some of the natural risks which are basically beyond our control but given the present technology some of these risks can be controlled or their impact lessened.

The Human Risk springs from human frailty and unpredictability.

Such Risks includes:

i. Personal risks such as high employee turnover, dishonesty, incompetence, carelessness, sickness, accidents, deaths, strikes etc.

ii. Customer risks such as non-payment of accounts and disproportionately high return or adjustment on items sold.

iii. Government risks such risks arise from the govt., taxation, regulations, price controls, wars, antidumping duties and customs tariffs etc.

The Market Risk:

Such risks are caused basically by price fluctuation in relation to time and place;

Time Risks:

The changes in prices with the passage of time, such fluctuations are related to the supply and demand equilibrium which in turn reflects such conditions as;

a. Saturation of the market,

b. Change in consumer demand,

c. New inventions and developments,

d. Actions of the competitors,

e. General business conditions, and

f. Seasonal fluctuations.

Place Risk:

The demand for and price of a commodity or a service do not remain constant at a given location, they vary from place to place. This variation is basically attributed to geographic conditions and differing demand at each business location.

Country Risk:

The purpose of this factor is to decide whether to trade or not with that country and/ or party. If the country risk factor is high (meaning risky business) and still business has to be done then the trader has to make sure for the recovery of the payment well in advance of actual shipment. On the other hand if the country risk factor is low (meaning stable country) in that case the trader can operate on normal trade terms.

This risk is mainly associated with the economic and political condition and policies of the country. Most of the global trading organizations get confidential reports on this factor from their bankers or there are specialized organizations that provide this information.

Generally there is no problem when dealing with developed countries or the developing countries, but problem arises when dealing with least developed countries or with countries having history of political unrest, economic instability, military regime etc.

The information on this factor is vital if an organization is planning for direct investment, but if the question is of normal trade then information on this factor helps the trader to decide the shipping and payment terms that the he can offer or receive from/to the country specific.

The checklist of various factors considered for evaluating the country risk is:

i. Foreign exchange reserves,

ii. Debt reservicing,

iii. Exchange rates and fluctuation against major hard currencies,

iv. History and current situation on political stability and/or instability,

v. Ethnic conflicts,

vi. Civil wars or situation conducive for such situations,

vii. Foreign Trade policies,

viii. Investment policies,

ix. Disputes with other trading countries,

x. Non-tariff barriers,

xi. Position at the WTO dispute settlement centre (including and dumping cases),

xii. Border disputes leading to armed conflicts in a low intensity war like situations,

xiii. Ratio of GDP and Defence expenditure,

xiv. Population with reference to middle income and poverty line,

xv. Infrastructure (land, air, ocean and telecommunication),

xvi. Power and water supply and consumption,

xvii. Industrial policies, and

xviii. Tax structures especially that segment affecting investment and repatriation.

Measures for the Handling of Risks:

There are three ways, by which the business risks are tackled by the organizations:

1. Absorption of risk.

2. Reduction of risk.

3. Shifting of risk.

1. Absorption of Risk:

When a business organization speculates on inventory for small profits, the attendant hazard of loss arising from risks peculiar to the business may make a policy of full risk absorption advisable. This practice requires capital over and above that needed for carrying on the business, and an extensive knowledge of many fields of trade.

For example in global trading business the trader always keeps enough reserves for any contingency resulting out of the business transactions. The extent of the reserves is proportionate to the net risk anticipated.

2. Reduction of Risk:

Several techniques may be utilized to reduce risks.

A business may;

(i) Change its organizational pattern;

(ii) Improve its management methods;

(iii) Increase the efficiency of its physical equipment; and

(iv) Make use of the R&D facilities.

(i) Alteration of Organizational Pattern:

A business firm may reorganize extensively to reduce risk. Reorganization may involve

a. Vertical integration.

b. Horizontal integration.

c. Associations and Combinations.

A vertically integrated organization is one, which controls several or all the steps necessary to the production of a commodity. It may also, if the integration is complete enough, control wholesale and retail distribution.

Thus some large oil companies own the production wells, the refineries, the pipeline or other transportation equipment needed to handle finished products and by-products, and the wholesale distribution facilities.

They may also own and operate retail establishments and international business. This vertical integration permits control of all processing steps from original collection of raw material to sale of the finished products to the ultimate consumers.

A horizontally integrated organization is one, which processes or fabricates several closely allied identical or competing products. These processes may take place in several different plants.

The word “horizontal” means that the process involved are in the same stage or level in the progressive refinement of the raw material into the finished product. Horizontal integration increases capacity; rising demand can be met without building new plants and going through all the exploratory steps in capital expansion.

Formation of associations and combinations. In many cases the competitors may combine to standardize trade practices. The individual company might benefit from such formations and standardization but in many cases it results in the formation of cartels or monopoly supply conditions. Such activities are illegal in general and consumers especially for the industrial products may resist such moves.

(ii) Improvement of Managerial Methods:

A business may reduce risk in the following way:

(a) Producing only on order. This practice keeps investment inventory at the minimum.

(b) Following just in time delivery system.

(c) Concentrating the suppliers of components and sub-assemblies in and around the main factory or the assembly line as is done by the automobile companies especially the Toyota car company.

(d) Diversification. For example a company which formerly produced only industrial products eventually found it necessary to produce consumer goods as well.

(e) Branding the product. The symbol or brand represents a definite quality or price. Branding reduces competition by marginal producers and in some cases increases a manufacturer’s control over the market.

(f) Careful grading, sorting, and standardizing of commodities.

(g) Budgetary planning and control accompanied by strict supervision of inventory.

(h) Effective use of the sales promotional channels.

(iii) Improvement of Physical Equipment:

Much business risk is inherent in the physical plant. Such safeguards as fireproof building, adequate vaults and protection from thefts will reduce not only risk but also the rates paid to insurance companies for assuming these risks. Take the case of large chain stores, they suffer badly from the thefts. Installing CTV and plain cloth security men has helped these stores globally.

On the other hand there could be instances when the question of scrapping the whole plant is involved for increasing the overall productivity and efficiency in production. Such cases are very frequent in steel making plants and chemical units. Even in the case of automobile production, which is heavily based on mass production techniques, the introduction of robot arm to do the repetitive jobs is another example.

At home, take the case of the casting industry which is chronically suffering from the use of aging machinery. No doubt such decisions are very expensive and crucial for the survival of the organization, if the survival is at stake then there is no alternative but to go for the new route.

(iv) Use of R&D:

R&D plays a vital role in the corporate survival in the present context of global presence and market share. The companies which spend time and money to have the best R&D system are able to take timely corrective measures to stay in the market by either innovation in the product or manipulation of the market forces including the changing demography and consumer tastes and preferences.

This is the most potent tool of risk neutralization but unfortunately in India not much emphasis is given to this aspect of the business. R&D has to be productive, effective and quality conscious.

3. Shifting of Risk:

A trader faced with substantial risks that cannot be reduced may shift the risk to some other person or institution.

Five of the most common devices for shifting risk are as follows:

(a) Averaging of risk,

(b) Risk shifting though sates,

(c) Contractual shifting of risk,

(d) Governmental assumption of risk, and

(e) Derivatives, Futures and Hedging.

(a) Averaging of Risk:

Insurance companies carefully study the risks to which the business is subjected and determine the probable incidence of losses. Insurance rates are based upon this statistical analysis of the probability. The payment of premium reimburses the insurance company for assuming the risk of the insured.

Insurance companies may, for a premium, assume risk of fire, theft, life, or credit loss, to name only a few of the most common risks. The statistical analysis made by the insurance company enables it to predict rather accurately how many fires will occur in a given year and what financial losses will result.

Knowing how much money will be required to pay claims, the insurance companies can then fix premiums for its insurance policies. The income from the premiums is used to settle claims and to meet the company’s operating expenses and profit margins.

(b) Risk Shifting through Sales:

A merchant with an extensive inventory may suddenly realize that his investment is in jeopardy because of unpredictable price fluctuations, errors in buying, changing tastes or styles, or a downward swing of the business cycle. To meet these unexpected risks, he can sell his goods at a reduced price. The risk is then borne by the purchaser who accepts it because of the price reduction.

(c) Contractual Shifting of Risk:

This type of risk shifting is very common in cases where the delivery period is long and commodity is affected by the price and/or currency fluctuations. The contracts in such cases contain clause permitting the seller to claim escalation of price in accordance with specified escalation formulae or as per some standard reference source. In the case of metal trade the LME price is taken as the standard reference price.

(d) Governmental Assumption of Risk:

Government often attempts to reduce risks for producers especially for the agricultural products. The parity price for certain crops like wheat and rice is an example. This means if the prices fall the government will purchase at the declared price so that the farmers can generate income and sustain their activities in normal fashion rather to be ruined.

(e) Derivatives, Futures and Hedging:

These are used for reducing trading (primary commodities) and financial risks (tradable financial instruments).

In the following part these three are explained:

J. Derivatives. A derivative is a financial instrument that does not constitute ownership, but a promise to convey ownership. Examples are options and futures. All derivatives are based on some underlying cash product.

These “Cash” Products are:

i. Spot Foreign Exchange.

This is the buying and selling of foreign currency at the exchange rates that you see quoted on the news. As these rates change relative to “home currency”, so one makes or loses money depending on the future movement.

ii. Commodities:

These include grain, pepper, raw cashew nuts, soya meal extract, coffee beans, rubber, etc.

iii. Equities.

iv. Bonds of Various Different varieties:

Bonds are medium to long-term negotiable debt securities issued by governments, government agencies, federal bodies (states), international financial organizations such as the World Bank, and companies.

Negotiable means that they may be freely traded without reference to the issuer of the security. That they are debt securities means that in the event the company goes bankrupt, bondholders will be repaid their debt in full before the holders of un-securitised debt get any of their principal back.

v. Short term (“money market”) negotiable debt securities such as T-Bills (issued by governments), Commercial Paper (issued by companies) or Bankers Acceptances. These are much like bonds, differing mainly in their maturity “Short term” is usually defined as being up to 1 year in maturity. “Medium term” is commonly taken to mean form 1 to 5 years in maturity and “long term” anything above that.

vi. Over the Counter (“OTC”) money market products such as loans/deposits. These products are based upon borrowing Or lending. They are known as “over the counter” because each trade is an individual contract between the 2 counterparties making the trade.

They are neither negotiable nor securitized. Hence if I lend your company money, I cannot trade that loan contract to someone else without your prior consent. Additionally if you default, I will not get paid until holders of your company’s debt securities are repaid in full. I will however, be paid in full before the equity holders get any money.

Derivative products are contracts, which have been constructed based on one of the “cash” products described above. Examples of these products include futures and options.

2. Futures:

Futures are commonly available in the following forms (defined by the underlying “cash” product):

i. Commodity futures.

ii. Stock index futures.

iii. Interest rate futures (including deposit futures, bill futures and government bond futures).

In the early 1990s, derivatives and their use by various large institutions became quite a hot topic, especially to regulatory agencies. What really concerns regulators is the fact that big banks swap all kinds of promises all the time, like interest rate swaps, forward currency swaps, options on futures, etc.

They try to balance all these promises (hedging), but there is the big danger that one big player will go bankrupt and leave lots of people holding worthless promises. Such a collapse could cascade, as more and more speculators (banks) cannot meet their obligations because they were counting on the defaulted contract to protect them from losses.

All of this is done off the books, so there is no total on how much exposure each bank has under a specific scenario. Some of the more complicated derivatives try to simulate a specific event by tracking it with other events (that will usually go in the same or the opposite direction). Examples are buying Japan stocks to protect against a loss in the US. However, if the usual correlation changes, big losses can be the result.

The big danger with the big banks is that while they can use derivatives to hedge risk, they can also use them as a way of taking ON risk. Not that risk is bad. Risk is how a bank makes money; for example, issuing loans is a risk.

However, banks are forbidden from taking on risk with derivatives. It’s just too easy for a bank to hedge bonds with derivatives that don’t have the same maturity, same underlying security, etc. so the correlation between the hedge and the risky position is weak.

Commodity markets are the markets for the primary products. Each such market gets its name from the product that it handles. Like the London Metal Exchange, Aluminum Exchange, Pepper Exchange etc.

There are four main factors that contributed in the establishment of commodity exchanges:

(i) Inelasticity of the price levels of the primary products.

(ii) Limited numbers of the primary products.

(iii) Large volumes involved.

(iv) Comparatively small producers and consumers and the long distances of their locations.

Take the case of the agriculture products. Small cultivators scattered over a large area produce these. The final purchasers are also scattered and centers of consumption are also scattered and mostly far away from the regions of production. An exchange is thus a convenient place where the collective produce of a large numbers of the farmers can be traded giving the farmers the advantages of a global open economy.

The dealers or the traders at the exchange facilitate the actual transactions. They are indispensable parts of the exchange operations. They facilitate the exchange of larger quantity of the products in physical terms.

The individual farmers generally lack the knowledge and the financial strength to handle the trading operations in isolation but the trader has both. This trader is known by different names in the actual operations of the commodity exchanges, as we will see later on in this paper.

There are two limiting factors that resulted in the creation of the traders or the middlemen:

1. Each producer is but a tiny fraction of the total output, his market is but a tiny fraction of the total market. Thus he cannot make any influence to the price level in the market place.

2. Each consumer is but a tiny consumer as compared to the total market consumption, as such he cannot make any influence on the market price.

The operational needs at the exchange are such that the trader while interacting with the buyers and sellers tends to take enormous risk on his account. This risk factor is related to the profitability expectations. The nature of the primary products is such that excessive margins are unthinkable. They normally rally on the continued movement of bulk cargo in the least operational time cycle.

In the primary commodities both the demand and supply in a short run are said to be inelastic. This means a fall in price does not have much effect in increasing the purchases and a rise in prices cannot quickly increase the supply. Supplies are subject to the natural variations and weather conditions.

Demands are subject to the variation in the activities in the centres of the industry and with the changes in the taste and the technical requirements. Under unregulated competition such markets are tormented with continual fluctuations in prices and. the volume of business.

Though dealers may mitigate this to some extent by building up stocks when prices are low and releasing them when demands are high. These types of buying and selling often turns into speculation, which tends to exacerbate the fluctuation.

The behaviour of primary commodity markets is a serious matter when whole of the communities depend upon a single commodity for income or for employment. The agricultural commodities that form part of an industrial economy are therefore generally protected from the operations of demand and supply by government regulations.

For example Australia have been able to make enough profits from the regulated export of primary commodities and make huge profits which are then used for other developmental activities. But in the case of the developing, they find their export earning insecure and insufficient. They generally perceive that the global market systems operate only for the industrialized nations.

It was this situation which resulted in the enactment of a legislation in USA in 1922 called the Grain Trading Act which prohibited any one from securing control over a single commodity in order to manipulate its prices. In 1936 the Commodity Exchange Act was enforced to further strengthen the Grain Trading Act.

This law also outlawed other types of speculation as well as fraudulent practices and excessively high brokerage fee charged by the traders. Finally the Commodity Exchange Authority was formed to enforce the law and to regulate the functioning of the commodity exchanges.

The future markets. From very early times and in many lines of trade, buyers and sellers have found it advantageous to enter into contracts- termed future contracts- calling for delivery of a commodity at a later date. Dutch whalers in the 16th century entered into forward sales contract before sailing. This they did partly to finance voyage and partly to get a better price for their product.

Another example could be that of the potato growers in Maine in USA. The growers used to make forward sales of potatoes at the planting time. The European future markets arose out of the import trade. Cotton importers in Liverpool for example entered into forward contracts with the US exporters from around 1840.

With the introduction of the Fast Transatlantic Cunard Mail services, it became possible for the cotton exporters in the US to send samples to Liverpool in advance of the slow cargo ships which carried bulk of the cotton. Future trading with in the United States in the form of “to arrive” contracts appears to have commenced before the railroad days (1850s) in Chicago.

Merchants in Chicago who bought wheat from the outlying territories were not sure when they would obtain delivery or what their quality would be. Under these conditions the introduction of the “to arrive” contracts enabled the sellers to get a better price for their products and the buyers to avoid serious price risks.

Further trading of this sort in grains, coffee, cotton, and oilseeds also arose in other countries such as Antwerp, Amsterdam, Bremen, Alexandria and Osaka between 17lh and the middle of the 19′h century. In the process of evolution, “to arrive” contracts became standardized with respect to grade and delivery period, with allowances for grade adjustment when the delivered grades happened to be different.

These developments helped to enlarge the volume of trade, encouraging more trading by merchants who dealt in the physical commodity and also entry of speculators. These speculators were interested not in the commodity itself but in the favourable movement of the price in order to make profits.

The larger volume of trading lowered the transaction costs, and by stages the trading became impersonal. The rise of the clearinghouses depersonalized the buyer-seller relations completely, giving rise to the present form of futures trading.

The commodity futures markets provided the insurance opportunity to the merchants and processors against the risk of price fluctuation. In the case of a trader an adverse price change brought either by supply or demand change affects the total value of his commitments, and the larger the value of his inventory, the larger the risk which he is exposed.

The future markets provides a mechanism for the trader to lower the per unit inventory risk on his commitments in the cash market, where actual physical delivery of the commodity must eventually be made, through what is known as hedging.

A trader is termed as hedger if his commitments in the cash market are offset by opposite commitments in the future markets. An example would be that of the grain elevator operator who buys wheat in the country and at the same time sells a future contract for the same quantity of wheat.

When his wheat is delivered later to the terminal market or to the processor in a normal market, he buys back his future contract. Any change in the price that occurred during the interval should have been cancelled out by mutually compensatory movements in his cash and future holdings.

The hedger thus hopes to protect himself against loss resulting from price changes by transferring the risk to a speculator who rallies upon his skill in forecasting price movements.

Cash Markets & Future Markets:

The cash market may either be a spot market concerned with immediate physical delivery of the specified commodity or a forward market where the delivery of the specified commodity is made at some later date.

Future markets generally permit trading in a number of grades of the commodity to protect the hedger seller from being cornered by speculator buyers who might otherwise insist on delivery of a particular grade whose stocks are small. Since a number of alternative grades can be tendered the future market is not suitable for the acquisition of the physical commodity.

For this reason physical delivery of the commodities in fulfillment of the future contracts generally does not take place and the contract is usually settled between buyers and sellers by paying the difference between the buying and selling prices.

Many future contracts in a commodity are traded during a year.

For Instance in USA:

Wheat contracts: Five; July, Sep, Dec, Mar and May.

Soybean contracts: Six; Sep, Nov, Jan, Mar, May and Jul.

These contracts are traded on the Board of Trade of the City of Chicago. The length of these contracts is for a period of about 10 months and a contract for “Sep wheat” or “Sep Soybean” indicates the month in which the contract will mature.

Though hedging is a form of insurance, it seldom provides perfect protection. The insurance is based on the fact that the cash and future prices move together and are well correlated.

The price spread between the cash and the futures is however not invariant. The hedger thus runs the risk that the price spread known as the “basis” could move against them. The possibility of such an unfavourable movement in the basis is known as the “basis risk”.

Thus the hedgers through their commitments in the future markets, substitute basis risk for the price risk they would have taken in carrying un-hedged stocks. It must be noted that the risk reduction is not the final objective with the merchants, traders and processors, what they all try to seek is to maximize the profits.

Banker’s Support:

The availability of the capital for financing the holding of the inventories depend on whether the goods are hedged or not. The banker’s willingness to finance them increases with the proportion of the inventory that is hedged. For example the bankers may advance loans to the extent of only say 50 % on the value of the un-hedged inventories and say about as much as 90% on the hedged inventories.

The reason is simple. Hedging reduces the risk on which the amount of the loan and the interest rate depend. Merchants and processors can derive two fold advantage from the future trading; they can insure against price decline and they insure larger and cheaper loans from the banks.

3. Hedging:

Hedging is a way of reducing some of the risk involved in holding an investment. There are many different risks against which one can hedge and many different methods of hedging. When someone mentions hedging, think of insurance. The trader buys or sells in accordance with his predictions concerning the direction or the extent of price fluctuations.

In hedging, he endeavours to eliminate potential losses. Hedging consists of the simultaneous purchase and sale of the same amount of one commodity in the cash and future markets on a specified date. At some future date these transactions are usually reversed in the two markets to complete the hedge.

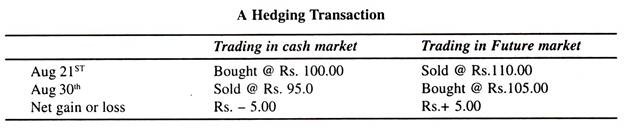

For example let us assume that a trader enters the market on 21st August, he buys in the cash market and sells in the future market. On 30lh August he sells in the cash market and buys in the future market.

Note that if the trader had operated only in the cash market he would have lost Rs. 5. To reduce the possibility of loss, he entered the futures market in the reverse direction. In this case, the spread between cash and futures prices amounting to Rs. 10 remained constant.

It is clear that hedging:

a. Provides considerable protection against losses from price changes,

b. Decreases marketing costs because operators require less margin,

c. Increases the effectiveness of competition since one needs less capital in order to enter the field,

d. Encourages loans because more stable prices reduce the risk of credit extension, and

e. Raises prices paid to producers since hedgers need not absorb all the risk.

A hedge is just a way of insuring an investment against risk:

Much of the risk in holding any particular stock is market risk: i.e. if the market falls sharply, chances are that any particular stock will fall too. So if you own a stock with good prospects but you think the stock market in general is overpriced, you may be well advised to hedge your position.

There are many ways of hedging against market risk. The simplest, but most expensive method is to buy a put option for the stock you own. (It’s most expensive because you’re buying insurance not only against market risk but against the risk of the specific security as well.) You can buy a put option on the market that will cover general market declines.

You can hedge by selling financial futures. The best hedge is to sell short the stock of a competitor to the company whose stock you hold. No matter which way the market as a whole goes, the offsetting positions hedge away the market risk.

Risk Reduction is the Prime Motive for Hedging:

The hedgers pay a risk premium to the speculators for assuming the risk. Under normal conditions in the commodity markets, when the demand, supply and spot prices are expected to remain unchanged for some months to come and there is uncertainty in the trader’s minds regarding these expectations, the future prices, say, for one month’s delivery is bound to be below the spot price that the traders expect to prevail one month later.

This condition exists because inventory holders would be ready to hedge themselves from the risk of price fluctuations by selling futures to speculators below the expected spot price. The inventory holders who hedge pay a risk premium to the speculators.

The hedging is done with the expectation of a profit from a favourable change in the spot-futures price relation, to simplify business decisions, and to cut costs, and not for the sake of reducing the risk alone. The hedgers take advantage of a temporary price difference between the two markets to buy in one and to sell in the other.

They thus speculate on the basis and assume risks. The need for hedging and the scope for hedging activities is that hedging is motivated by the desire to reduce risks. The level of inventory held by merchants and processors are determined by expected hedging profits.

Short and Long Hedgers:

There are two categories of the hedgers in the futures markets. They are called short and long hedgers.

The short hedgers are merchants and processors who acquire inventories of the commodity in the spot markets and who simultaneously sell an equivalent amount or less in the futures market. The hedgers in this case are said to be long on their spot transactions and short on their futures transactions.

Example:

Wheat merchants or the wheat flour mills who either have 100,000 MTS of wheat as inventory or have bought it for later delivery are said to short hedge if they sell 100,000 MTS of wheat in the futures contracts. By holding inventories both merchants and processors can make their purchases when it is most opportune and lower their transaction costs through fewer transactions.

Another advantage to the processing firm in holding inventory is that it makes it possible to avoid interruption in production. Short hedgers do not normally deliver the physical commodity in fulfillment of the futures contract. They “lift the hedge” by repurchasing the futures contracts at the prevailing futures price when they sell the raw material or the processed goods in the spot market.

The merchants and the processors do not generally hedge all their inventories for the sake of reduced risk. The decision on what part of the inventories to hedge is based on their expectations relating to return from holding hedged and un hedged inventories in storage, given the cost incurred in both forms of inventory holding.

The return per unit to merchants and processors on their hedged inventories, when liquidated, is the change in the spot price less the change in the futures price and the storage cost. Their return on per unit un-hedged inventory is the change in the spot price less the storage costs.

The long hedgers are the merchants and the processors who have made formal commitments to deliver a specified quantity of the raw material or the processed goods at a later date at a price currently agreed upon and who do not now have the stock of the raw material necessary to fulfill their forward commitment.

The parties who have made the commitment generally seek to hedge against the risk of price rise in the raw material between the time of making the forward contract and the time of acquiring the raw material stock for fulfilling the contract. The hedging is done by buying future contracts of the raw material equal in quantity to what is needed to fulfill the forward commitment.

There are many situations which prompt the hedger to make decisions whether to buy now or in futures, how much to buy and how much to postpone for later consideration etc. For instance under what circumstances the long hedger might prefer the purchase of futures to the alternative of immediately buying the raw material through spot or forward purchase to meet the obligation of his forward sale.

The answer to this situation might vary from hedger to hedger but in general the hedger might prefer buying futures to buying in the cash market (spot or forward) if current cash prices are high because of scarcity. Generally there is an increase in the amount of long hedging when, as the season advances, spot prices rise, inventory holding fall and the new crop is not yet available.

The long hedging is not as risk-reducing as it may appear at the first sight. The long hedger processor who buys raw material futures to satisfy his forward commitment of the processed goods may find that the raw material delivered to him in futures is not of suitable grade and quality to meet the obligations of the forward sale.

Quite often he may sell his futures contract and may purchase raw material of the grade needed. If the spot price of the raw material moves unfavourably relative to the price of the processed goods sold forward by him, the long hedger actually increases the risk by buying the futures instead of buying the raw material in the cash market.

Long hedging, unlike short hedging, may serve to increase risk, and the total risk on long hedging increases with the size of the commitment.

The volume of the short hedging tends to be large when stocks in commercial hands are large and when the cash price is below the futures price; a reversal in this situation brings decline. Conversely, the volume of long hedging is large when the stocks are small and the cash price is above the future price.

Short hedging has marked seasonal pattern, reaching the peak when the commercial stocks are largest and the basis is favourable and then declining as the season advances. The seasonal pattern is less marked in long hedging. Generally there is an excess of short over long hedging during the bulk of the crop year.

Speculators:

In addition to hedgers, the futures markets also include speculators. The speculators are of two categories. The long speculators and the short speculators. The long speculators are those who expect the price to rise above the current level and assume risks by purchasing the futures contracts. Short speculators are those who expect the price to fall. They sell futures contracts.

In a futures market the total short selling position, made up of short hedgers and short speculators, and the total long buying position, made up of long hedgers and long speculators, must always be equal. An equal excess of long over short speculation must balance any excess of short over long hedging.

Since short hedging exceed long hedging for most of the crop year, hedgers are generally short and speculators are generally long.

Futures markets have flourished and became important in commodities where sizable inventories have to be stored and carried forward for meeting the consumption needs of the entire season. Successful futures trading requires a large volume with low transaction costs and that spot and futures prices be well correlated in order to make hedging effective.

Important Futures Markets:

Based on the number and volume of commodities, in which active futures trading exists, the USA occupies first position. The Chicago Board of Trade, the largest of the world’s futures markets in terms of volume and value of business, is the center of trading in Wheat, Corn, Oats, Rye, Soybean, Soybean oil, and Soybean meal.

About 30 commodities in all are traded on organized exchanges in the USA. The wheat market in Minneapolis, the cotton and wool market in New York city, and the markets in frozen pork bellies and live hogs in the Midwestern United States are among them. The number of commodities in which futures trading takes place are fewer outside the USA.

The future markets outside the USA are:

Wool: London, Paris and Bombay

Sugar: London and Paris

Jute goods: Calcutta, India

Pepper: Cochin, India

Turmeric: Sangali, India

Soyameal: Indore, India

As a result of governmental controls on futures markets and also of international commodity agreements, the volume of futures trading in several countries is adversely affected. The commodity markets in Europe, with few exceptions, have been dormant since World War II.

Many of the Indian commodity markets such as those in Gur, Jute and Oil seeds, which were once active, have met the same fate. The recurrent arguments in the USA, India, and elsewhere against the futures markets are that they encourage speculation and that the participation of the speculators causes price instability.

These arguments have led to the demand that markets be controlled or prohibited from functioning. To refute such allegations requires a comparison between price variation in the presence and absence of speculators which is impossible for commodities that have futures markets, since it is not meaningful to say for these markets what the price would have been in the absence of speculators.

The Case for the Manufactured Goods:

The manufactured goods are not suitable for the commodity exchange operations because of their nature and related demand and supply norms. These are manufactured by individual companies, having own style, reputation, location, distribution channels, advertisement or in brief each company has its own marketing system for putting the products in the market place.

The distribution channels play an important role in fixing the net price to the ultimate consumer. Even some times the same product is differentiated to target at different market segments, like cigarettes for men and women, soaps for men, women and children etc.

In such type of market supply is normally responsive to demand in the short run. Stocks or inventories are held at some point in the chain of distribution; while the stocks are running down or building up there is time to change the level of production, and once a price has been set, it is rarely altered in response to moderate changes in demand.

Even in a deep slump, defensive rings may often be formed to prevent price-cutting. In the long run as well short, supply is responsive to demand in the market for manufacturers. It is easier to change the composition of a firm’s output than it is to change the production of a mine or plantation.

These attributes of the finished goods and their markets do not make them a perfect item to be traded on the commodity type exchange.