Here is a term paper on ‘Perception’ for class 9, 10, 11 and 12. Find paragraphs, long and short term papers on ‘Perception’ especially written for school and college students.

Term Paper on Perception

Term Paper Contents:

- Term Paper on the Meaning and Definition of Perception

- Term Paper on the Significance and Importance of Perception

- Term Paper on the Perceptual Process/Perceptual Mechanism/Elements of Perception

- Term Paper on the Factors Influencing Perceptual Mechanism

- Term Paper on the Attribution Theory of Perception

- Term Paper on Selective Perception

- Term Paper on Halo Effect and Perception

- Term Paper on Perceptual Constancy

- Term Paper on Perceptual Defence

- Term Paper on Perceptual Context

- Term Paper on Stereotyping and Perception

- Term Paper on Projection

- Term Paper on Perceptual Change

- Term Paper on Sensation

- Term Paper on the Perceptual Organisation

Term Paper # 1. Meaning and Definition of Perception:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Human beings are constantly attacked by numerous sensory stimulations including noise, sight, smell, taste etc. The critical question in the study of perception is why the same unit is viewed differently by different persons? The answer is the perception. Different people perceive the universe differently.

Perception is the process through which the information from outside environment is selected, received, organised and interpreted to make it meaningful to us. This input of meaningful information results in decisions and actions. It is a result of a complex interaction of various senses such as feeling, seeing, hearing, thinking and comparing with known aspects of life in order to make some sense of the world around us. The quality or accuracy of a person’s perception is an important factor in determining the quality of the decisions and action.

“Perception can be defined as a process by which individuals organise and interpret their sensory empressions in order to give meaning to their environments”. – Stephen P. Robbins

“Perception is the process of becoming aware of situations of adding meaningful associations to sensations”. – B. Von Haller Gilmer

ADVERTISEMENTS:

“Perception includes all those processes by which an individual receives information about his environment—seeing, hearing, feeling, tasting and smelling. The study of these perceptional processes shows that their functioning is affected by three classes of variables— the objects or events being perceived, the environment in which perception occurs and the individual doing the perceiving”. – H. Joseph Reitz

“Perception can be defined as the process of receiving, selecting, organising, interpreting, checking and reacting to sensory stimuli or data”. – Udai Pareek

Perception is defined as the process by which an individual selects, organizes, and interprets stimuli into a meaningful and coherent picture of the world. A stimulus is any unit of input of any of the senses. Sensory receptors are the human organs as the eyes, ears, noise, mouth and skin, they receive the sensory input. There sensory functions are to see, hear, smell, taste, and feel. The study of perception is largely the study of what we subconsciously add to or subtract from raw sensory inputs to produce our own private picture of the world.

According to Kolasa, the perception involves two basic elements:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

(a) Perception is the process of selection or screening which prevents us from processing irrelevant or disruptive information.

(b) There is organisation implying that the information which is processed has to be ordered and classified in some logical manner which permits us to assign meaning to the stimulus situations.

Term Paper # 2. Significance and Importance of Perception:

Every person perceives the world and approaches the life problems differently. This factor is very important in understanding human behaviour. The world as we see is not necessarily the same as it really is. It is because what we hear is not what is really said. We buy what we like best and not what is best. It is because of perception that a particular job may appear a good job to one and bad to another.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Due to perception only ‘facts’ as they are seen by one viewer, may be different from the facts as seen by another viewer. The tension or discomfort that one feels when he thinks he is missing something, others may not realise it. Everyone wears his own rose-coloured glasses, i.e., one does not always see that is actually happening. If people behave on the basis of their perceptions, then changing behaviour in a predetermined direction can be made easier by understanding their present perception of the world.

People act as they perceive and different people perceive things differently. People’s perception is determined by their needs. Like the mirrors at an amusement park, they distort the world in relation to their tensions. If people are asked to describe the people they work with, they talk more about their boss than their colleagues because of their continuous worry to please the boss.

Perception is important dynamite for the manager who wants to avoid making errors when dealing with people and events in the work setting. This problem is made even complicated by the fact that different people may perceive the same situation in different ways. A manager’s response to a situation, for example, may be misinterpreted by a subordinate who perceives the situation quite differently. In order to deal with the subordinates effectively, a manager must understand their perceptions properly.

Term Paper # 3. Perceptual Process/Perceptual Mechanism/Elements of Perception:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Perception is the process that operates constantly between us and reality.

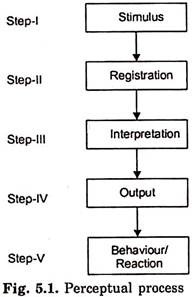

Perception process involves the following steps:

Step-I:

Stimulus:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Perception initiates with the presence of the stimulus situation.

Step-II:

Registration:

It involves the physiological mechanism both sensory and neutral. Obviously, an individual’s physiological ability to hear and see determines his perception.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Step-III:

Interpretation:

It is the highly crucial sub process. Without the interpretation of the perceived events, the perceived world would be meaningless. Interpretation is subjective and judgmental process. In organisations interpretation is influenced by many factors such as halo effect, stereotyping, attribution, impression and inference.

Step-IV:

Output:

As a result of, perceptual process, the outputs which the individual gets as changes in the attitudes, opinions, beliefs, feelings, etc.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Step-V:

Behaviour:

The perceiver’s behaviour is shaped by the perceived output i.e., changes in attitudes, opinions, beliefs etc. The perceiver’s behaviour generates responses depending upon the situation and these responses further give rise to a new set of inputs.

Term Paper # 4. Factors Influencing Perceptual Mechanism:

External Factors:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

These include:

(a) Intensity:

High intensity increases the chances of selection. If the message is bright, if sentences are underlined it get more attention than in normal case. The greater the intensity of stimulus, the more likely it will be noticed. An intense stimulus has more power to push itself our selection filters than does the weak stimulus.

(b) Size:

Size establishes dominance and overrides other things and thereby enhances perceptual selection. The bigger the size of perceived stimulus, higher is the probability that it is perceived.

(c) Frequency:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

A repeated external stimulus is more attention getting than a single one. A stimulus that is repeated has a better chance of catching us. Repetition increases our sensitivity and alertness to the stimulus. Thus, the greater the frequency with which a sensory stimulus is presented, the greater the chances we select it for attention. Repetition is one of the most frequently used techniques in advertising and is the most common way of getting our attention. Repetition aids in increasing the awareness of the stimulus.

(d) Status:

Perception is also influenced by the status of perceiver. High status people can exert influence on perception of employees than low status people.

(e) Contrast:

Stimuli that contrast with the surrounding environment are more likely to be selected for attention than the stimuli that blends in. A contrasting effect can cause by colour/size or any other factor that is unusual. The contrast principle states that external stimuli that stands out against the background or which are not what are expecting will receive their attention. The contrast effect also explains why a male person stands out in a crowd of females.

Internal Factors:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

These include:

(a) Needs and Desires:

The needs and motives of the people play a vital role in perception. Perception of a frustrated person would be entirely different than that of a happy going person. People at different level of needs and desires perceive the same thing differently. Power seekers are more likely to notice power related stimuli. Socially oriented people pay attention to interpersonal stimuli. People will likely to notice stimuli relevant to current active motives and compatible with major personality characteristics.

(b) Experience:

Experience and knowledge have a constant bearing on perception. Successful experiences enhance and boost the perceptive ability and lead to accuracy in perception of a person whereas failure erodes self-confidence.

(c) Personality:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Personality is another important factor that has a profound influence on perceived behaviour. Optimistic people perceive the things in favourable terms while pessimistic perceive in negative terms. According to Maslow, “that between these two extremes there exist a category that can see things more accurately and subjectively. Research on the effects of individual personality on perception reveals many truths.”

i. Thoughtful individuals do not expose by expressing extreme judgments of others.

ii. Persons who accept themselves and have faith in their individuality perceive things favourably.

iii. Secured individuals tend to perceive others as warm, not cold.

Term Paper # 5. Attribution Theory of Perception:

The perceptions of people differ from our perceptions because we make inferences about the actions of people that we don’t make about inanimate objects.

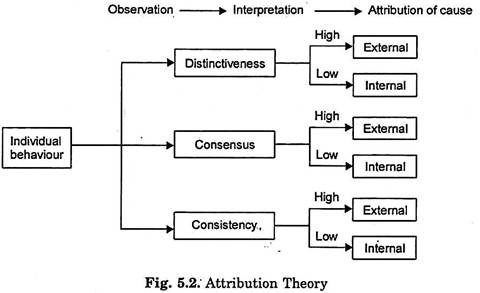

Attribution theory has been proposed to develop explanations of the ways in which we judge people differently, depending on what meaning we attribute to a given behaviour. Basically, the theory suggests that we observe an individual’s behaviour; we attempt to determine whether it was internally or externally caused.

That determination, however, depends largely on three factors:

1. Distinctiveness,

2. Consensus, and

3. Consistency.

First, let’s clarify the differences between internal and external causation and then we will elaborate on each of the three determining factors.

Internally caused behaviours are those that are believed to be under the personal control of the individual. Externally caused behaviour is seen as resulting from outside causes, that is, the person is seen as forced into the behaviour by the situation. If one of our employees is late for work, we might attribute his lateness to his partying into the hours of the morning and then over-sleeping. This would be an internal attribution. But if we attribute his arriving late to a major automobile accident that tied up traffic on the road that this employee regularly uses, then we would be making an external attribution.

Distinctiveness refers to whether an individual displays different behaviours in different situations. Is the employee who arrives late today also the source of complaints by coworkers? What we want to know is, if this behaviour is unusual or not. If it is, the observer is likely to give the behaviour an external attribution. If this action is not unusual, it will probably be judged as internal.

If everyone who is faced with a similar situation responds in the same way, we can say the behaviour shows consensus. Our late employee’s behaviour would meet this criterion if all employees who took the same route to work were also late. From an attribution perspective if consensus is high, we would be expected to give an external attribution to the employee’s tardiness, where as if other employees who took the same route made it into work on time, our conclusion as to causation would be internal.

Finally, an observer looks for consistency in a person’s actions. Does the person respond the same way over time? Coming in ten minutes late for work is not perceived in the same way for the employee for whom it is an usual case (he hasn’t been late for several months), as for the employee for whom it is part of routine pattern (he is regularly late two or three times a week). The more consistent the behaviour, the more the observer is inclined to attribute it to internal causes.

Fig. 5.2 summarizes the key elements in attribution theory. It would tell us, for instance, that if an employee performs at about the same level on other related tasks as he does on his current task (low distinctiveness), if other employees frequently perform differently better or worse than employee does on that current task (low consensus), and if employee’s performance on this current task is consistent over time (high consistency), their manager or anyone else who is judging employee’s work is likely to hold him primarily responsible for his task performance (internal attribution).

One of the more interesting findings from attribution theory is that there are errors or biases that distort attributions. For instance, there is substantial evidence that when we make judgements about the behaviour of other people, we have a tendency to underestimate the influence of external factors and overestimate the influence of internal or personal factors.

This is called the fundamental attribution error and can explain why a sales manager is prone to attribute the poor performance of his sales agents to laziness rather than the innovative product line introduced by a competitor. There is also a tendency in individuals to attribute their own successes to internal factors like ability or effort while putting the blame for failure on external factors like luck. This is called the self-serving bias and suggests that feedback provided to employees in performance reviews will be predictably distorted by recipients depending on whether it is positive or negative.

Term Paper # 6. Selective Perception:

We are confronted with stimuli all the times and the stimuli are innumerable. Since we cannot observe everything going on about us, we are engaged in selective perception.

The other important question arises how we use shortcut in judging other people? Simply, since we cannot assimilate all that we observe, we take in bits and pieces. But these bits and pieces are not chosen randomly rather they are selectively chosen depending upon the interest, background, experience and attitudes of the observer. Selective perception allow us to speedily read others, but not without the risk of drawing an inaccurate picture. Because we see what we want to see, can draw unwarranted conclusions from an ambiguous situation.

Term Paper # 7. Halo Effect and Perception:

When we draw a general impression about an individual based on single characteristics such as intelligence, sociability or appearance, a halo effect is operating. This phenomenon frequently occurs when students appraise their class room teacher. Students may isolate a simple trait such as enthusiasm and allow their entire evaluation to be trained by how they judge the instructor on this one trait. Thus, the instructor may be quiet, assured, knowledgeable and highly qualified, but if his style lacks zeal, he will be rated lower on a number of other characteristics.

The propensity for the halo effect to operate is not random. Research suggests that it is likely to be more extreme when the traits to be perceived are ambiguous or unclear in behavioural terms and when the perceiver is judging traits with which he has had limited experience.

In organisations, the halo effect is important in understanding an individual’s behaviour, particularly when judgement and evaluation must be made. It is not unusual for the halo effect to occur in selection interviews or at the performance appraisal time. A dirty dressed candidate may be treated as careless person with the unprofessional attitude, when in fact the candidate may be highly responsible, professional and highly competent. The halo effect can have a similarly distorting impact on performance evaluation, causing the full appraisal to be biased by a single trait.

Term Paper # 8. Perceptual Constancy:

It deals with the stability in changing environment or world. Moskowitz and Orgel observed that constancy permits the individual to interpret the kaleidoscopic variability of proximal stimuli in such a manner that these same stimuli more or less accurately reflects the constancies of the real world, the stability and un-changeability of objects and people, the consistency of three dimensionality of our everyday world.

If constancy principle is not at work the world become a chaotic and disorganized for the individual. Without perceptual constancy, the shape, sizes, colours of the objects would change as the person moves about and this makes his job uncomfortable and sometimes impossible.

According to Kendler, perceptual constancy does not result from ignoring any particular cue; it results from responding the patterns of cues. These cues are mostly learned by the individuals but with each situation the interaction between learned and inborn tendencies occur within the entire perceptual process. The sins of perceptual constancy are that the shape, size, colour, brightness and location of an object are reasonably and fairly constant regardless of the information received by senses.

Term Paper # 9. Perceptual Defence:

People often screen out perceptual stimuli that make them uncomfortable and dissatisfying. People have certain inherent tendencies to defend their reactions against new information which would be conflicting with their existing impressions.

Perceptual defence is performed by:

(a) Denying the existence or importance of conflicting information,

(b) Distorting the new information to match the old.

(c) Acknowledging the existence of new information but treating it as a non- representative exception.

People generally build defences against stimuli or events that are either personally or culturally unacceptable or threatening. From the view point of the organisation, perceptual defence plays an influential role in understanding superior-subordinate relationship.

Term Paper # 10. Perceptual Context:

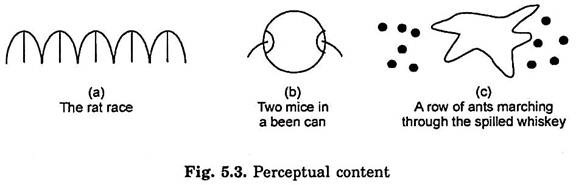

Context is very important in order to give meaning and value to stimuli, objects, events and situations. The principle of context can be demonstrated by the well-known doodles as shown in fig. 5.3.

The visual stimuli without context become completely meaningless. But when the doodles are placed in verbal context they take on meaning and some value to the person who perceives.

In the organisation, a pat on the back, a suggestive gesture, a raised eyebrow etc., will be meaningless without proper context. They will be made more meaningful if an employee receives a pat on the back for enhancement in his performance and like that.

Term Paper # 11. Stereotyping and Perception:

When we judge someone on the basis of our perception of the group to which he belongs, it is called as .stereotyping. It is some sort of generalization as we judge a person on the basis of the group to which members interact. Generalization has the advantage as it is very difficult to deal with unmanageable number of stimuli and if we use stereotypes then we can judge a person on the basis of a group. But it has a problem as two persons do not have the same characteristics. As, all sales people are not aggressive and talkative.

The other problem with the stereotyping is that if persons are so widely spread the estimate may become irrelevant. Here, the judge can form inaccurate perception based on the false premise about a group.

Term Paper # 12. Projection:

It is easy to judge others if they assume that they are similar to us. For instance, if we want challenge and responsibility in our job, we assume that others want the same. This tendency to attribute one’s own characteristics to other people is called as projection. When managers are engaged in projection, they compromise their ability to respond to individual differences. They tend to see people more homogeneous than they really are.

As defined by Freud, projection refers to a mechanism which people adopt for defending themselves against unacceptable feelings. Suppose a subordinate is actually angry with his boss but cannot entertain the thought of showing this anger. To escape from the resulting sense of guilt he may tell himself: “My boss is very unfair and cruel person.” The attribution of unfairness and cruelty to the boss relieves the subordinate of the feeling of guilt, this is how projection in its Freudean sense, works.

Later, however, the concept of projection was extended to include the ascription of any of one’s own characteristics to other people. An experiment showed that after a game of “murder” the subjects attributed much greater maliciousness to people than did the numbers of the control group who had not played the game. Frightened people have a tendency to see others as frightened and angry people tend to see others as angry. People also tend to see in others those undesirable personality characteristics which they see in themselves.

Similarly, people high on stringiness, obstinacy and disorderliness have been found to rate others much higher on these traits than those who possess these characteristics in a lesser measure. The degree of insight that a person has into his own personality significantly affects his tendency to project. The greater the insight, the less the projection, and vice- versa. The mechanism of projection has important implications for a manager.

Faced with organisational changes, a manager may feel threatened. He may then frame organisational policies according to that perception, which can be really counterproductive.

Term Paper # 13. Perceptual Change:

If perception, as described, is a transaction between the individual and the outside world in order that reality may become predictable, what are the conditions under which perceptual changes occur? Is a mere rational, logical or intellectual understanding of one’s own perceptual tendencies or situations enough to bring about perceptual change? The answer is, No. The prime condition for perceptual change is frustration.

When faced with frustration, a person is ready to change his perception. Research in the field of opinion and attitude change has demonstrated this fact beyond doubt. People working in a distorted room continued to believe that the room was square until it become impossible for them to achieve their objectives with the faulty perception. Only then were they able to see that the room was distorted.

Another condition for perceptual change is the desire, willingness and determination to bring about such a change. As John Powell says, perceptual change comes through awareness of one’s perceptions and perceptual frame work. This is possible only when there is willingness, desire, and determination.

Some other thinkers point out that, in some situations, determination may have negative effects. They advocate observation of self, processes as they occur, accompanied by purpose, analysis and interpretation. The very act of observation, they assert, breaks the influences of the past operating on perceptual processes, and frees it of all sources of possible distortions.

Term Paper # 14. Sensation:

Sensation is the immediate and direct response of the sensory organs to simple stimuli. Human sensitivity refers to the experience of sensation. Sensitivity to stimuli varies with the quality of an individual’s sensory receptors (e.g., eye sight or hearing) and the amount of intensity of the stimuli to which he is exposed. For example, a blind person may have a more highly developed sense of hearing than the average sighted person and may be able to hear sounds that the average person cannot.

Perception refers to interpretation of sensory data. In other words, sensation involves detecting the presence of a stimulus whereas perception involves understanding what the stimulus means. For example, when we see something, the visual stimulus is the light energy reflected from the external world and the eye becomes the sensor. The visual image of the external thing becomes perception when it is interpreted in the visual cortex of the brain. Thus, visual perception refers to interpreting the image of the external world projected on the retina of the eye and constructing a model of the three dimensional world.

Sensation itself depends on energy change or differentiation of input. A perfectly bland or unchanging environment regardless of the strength of the sensory input provides little or no sensation at all.

As sensory input decreases, however, our ability to detect changes in input or intensity increases, to the point that we attain maximum sensitivity under conditions of minimal stimulation. This accounts for the statement, “it was so quiet I could hear a pin drop.”

It also accounts for the increased attention given to a commercial that appears alone during a programme break, or to a black and white advertisement in a magazine full of four colour advertisements. This ability of the human organism to accommodate itself to varying levels of sensitivity when it is needed, but also serves to protect us from damaging, disruptive, or irrelevant bombardment when input level is high.

The Absolute Threshold:

The lowest level at which an individual can experience a sensation is called the absolute threshold. The point at which a person can detect a difference between something and nothing is that person’s absolute threshold for that stimulus.

Under the conditions of constant stimulation the absolute threshold increases (i.e., the senses tend to become increasingly dulled). Hence, we often speak of getting used to a hot bath, a cold shower, the bright sun. In the field of perception, the term adaptation refers specifically to getting used to certain sensations, becoming accommodated to a certain level of stimulation.

Sensory adaptation is a problem experienced by many TV advertisers during special programming events, such as the Olympic Games or cricket world cup. For example, with many brilliantly executed commercials all competing with one another as well as with the Olympic Games or world cup themselves for viewer attention, often no one commercial will stand out from all the rest.

It is because of adaptation that advertisers tend to change their advertising campaigns regularly. They are concerned that consumers will get so used to their current print advertisements and TV commercials that they will no longer see them, i.e., the ads will no longer provide sufficient sensory input to be noted.

The Differential Threshold:

The minimal difference that can be detected between two stimuli is called the differential threshold or the J.N.D. (for just noticeable difference). German Scientist Ernst Weber discovered that the just noticeable difference between two stimuli was not an absolute amount, but an amount relative to the intensity of the first stimulus. Weber law states that the stronger the initial stimulus, the greater the additional intensity needed for the second stimulus to be perceived as difference.

For example, if the price of an automobile is increased by one thousand rupees, it would fall below the J.N.D. It may take an increase of five thousand rupees or more before a differential in price would be noticed. However, a one rupee increase in the price of kerosene would be noticed very quickly by consumers because it is a significant percentage of the initial (i.e., base) cost of the kerosene.

According to Weber’s law, an additional level of stimulus equivalent to the J.N.D. must be added for the majority of people to perceive a difference between the resulting stimulus and the initial stimulus. Weber’s law holds for all the senses and for almost all intensities (e.g., for sight and sound).

Term Paper # 15. Perceptual Organisation:

People do not experience the numerous stimuli they select from the environment as separate and discrete sensations, rather they tend to organise them into groups and perceive them as unified wholes. Thus, the perceived characteristics of even the simplest stimulus are viewed as a function of the whole to which the stimulus appears to belong. The method of organisation simplifies life considerably of the individual.

The specific principles underlying perceptual organisation as often referred to by the name given by the school of psychology that first developed it Gestalt psychology. (Gestalt in German means pattern or configuration).

Three of the most basic principles of perceptual organisation are:

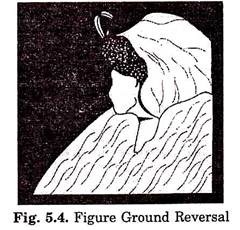

1. Figure and Ground:

Stimuli that contrast with their environment are more likely to be noticed. A sound must be louder or softer, a colour brighter or paler. The simplest visual illustration consists of a figure on a ground, it appears to be well defined, solid, and in the forefront. The ground however, is usually perceived as indefinite, lazy and continuous.

The common line that separates the figure and the ground is perceived as belonging to the figure rather than to the ground, which helps give the figure greater definition, consider the stimulus of music. People can either ‘bathe’ in music or listen to music. In the first case, music is simply ground to other activities, in the second, it is figure. Figure is more clearly perceived because it appears to be dominant; in contrast ground appears to be subordinate and, therefore less important.

People have a tendency to organise their perception into figure 5.4 and ground relationship. However, learning affects which stimuli are perceived as figure and which as ground. We are all familiar with reversible figure ground patterns, such as the picture of the woman in Fig. 5.4.

How old would you say she was? Look again, very carefully. Depending on how you perceive figure and how you perceive ground, she can be either in her early twenties or her late seventies.

Like perceptual selection, perceptual organisation is affected by motives and by exceptions based on experience. For example, how a reversible figure ground pattern is perceived can be influenced by prior pleasant or painful associations with one or the other element in isolation. The consumer’s physical state can also affect how he or she perceives reversible figure ground illustrations.

For example, after returning to work after an automobile accident and resultant brain concussion, the 35 years old secretary happened to note with surprise the picture of the old woman. It took a great deal of concentrated effort for her to recognise it as the reversal of the picture of the smartly dressed young woman that she had been accustomed to seeing on the author’s desk.

2. Grouping:

Individuals tend to group stimuli automatically so that they form a unified picture or impression. The perception of stimuli as groups or chunks of information, rather than as discrete bits of information, facilitates their memory and recall.

3. Closure:

Individual have a need for closure. They express this need by organising their perceptions so that they form a complete picture. If the pattern of stimuli to which they are exposed to is incomplete, they tend to perceive it nevertheless as complete; that is they consciously or subconsciously fill in the missing pieces.

Thus, a circle with a section of its periphery missing will invariably be perceived as a circle and not as an arc. The need for closure is also seen in the tension as individual experiences when a task is incomplete, and the satisfaction and relief that come with its completion.

In summary, it is clear that perceptions are not equivalent to the raw sensory input of discrete stimuli or to the sum total of discrete stimuli. Rather, people tend to add to or subtract from stimuli to which they are exposed according to their expectations and motives, using generalized principles of organisation based on Gestalt theory.