Here is an term paper on the ‘Models of Organisational Behaviour’ for class 11 and 12. Find paragraphs, long and short term papers on the ‘Models of Organisational Behaviour’ especially written for college and management students.

The model of organizational behaviour which predominates among the management of an organization will affect the success of that whole organization. And at a national level the model which prevails within a country will influence the productivity and economic development of that nation. Models of organizational behaviour are a significant variable in the life of all groups.

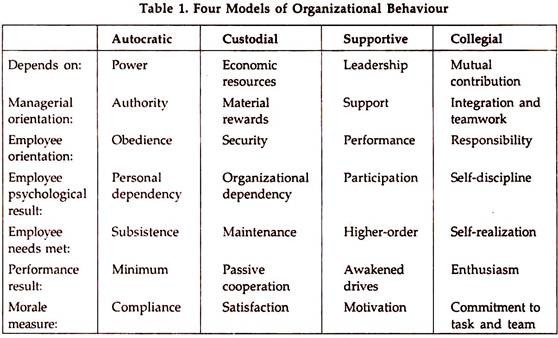

Many models of organizational behaviour have appeared during the last 100 years, and four of them are significant and different enough to merit further discussion. These are the autocratic, custodial, supportive, and collegial models. In the order mentioned, the four models represent a historical evolution of management thought.

The four models are not distinct in the sense that a manager or a firm uses one and only one of them. In a week—or even a day—a manager probably applies some of all four models. On the other hand one model tends to predominate as his habitual way of working with his people, in such a way that it leads to a particular type of teamwork and behavioural climate among his group.

Term Paper # 1. The Autocratic Model of Organizational Behaviour:

The autocratic model has its roots deep in history, and certainly it became the prevailing model early in the industrial revolution. As shown in Table 1, this model depends on power. Those who are in command must have the power to demand, “You do this—or else,” meaning that an employee will be penalized if he does not follow orders. This model takes a threatening approach, depending on negative motivation backed by power.

In an autocratic environment the managerial orientation is formal, official authority. Authority is the tool with which management works and the context in which “it thinks, because it is the organizational means by which power is applied”. This authority is delegated by right of command over the people to whom it applies.

In this model, management implicitly assumes that it knows what is best and that it is the employee’s obligation to follow orders, without question or interpretation. Management assumes that employees are passive and even resistant to organizational needs. They have to be persuaded and pushed into performance, and this is management’s task. Management does the thinking; the employees obey the orders.

This is the “Theory X” popularized by Douglas McGregor as the conventional view of management. It has its roots in history and was made explicit by Frederick W. Taylor’s concepts of scientific management. Though Taylor’s writings show that he had worker interests at heart, he saw those interests served best by a manager who scientifically determined what a worker should do and then saw that he did it. The worker’s role was to perform as he was ordered.

Under autocratic conditions an employee’s orientation is obedience. He bends to the authority of a boss—not a manager. This role causes a psychological result which in this case is employee personal dependency on his boss whose power to hire, fire, and “perspire” him is almost absolute.

The boss pays relatively low wages because he gets relatively less performance from the employee. Each employee must provide subsistence needs for himself and his family; so he reluctantly gives minimum performance, but he is not motivated to give much more than that. A few men give higher performance because of internal achievement drives, because they personally like their boss, because the boss is a “natural-born leader,” or because of some other fortuitous reason; but most men give only minimum performance.

When an autocratic model of organizational behaviour exists, the measure of an employee’s morale is usually his compliance with rules and orders. Compliance is un-protesting assent without enthusiasm. The compliant employee takes his orders and does not talk back.

Although modern observers have an inherent tendency to condemn the autocratic model of organizational behaviour, it is a useful way to accomplish work. It has been successfully applied by the empire builders of the 1800s, efficiency engineers, scientific managers, factory foremen, and others. It helped to build great railroad systems, operate giant steel mills, and produce a dynamic industrial civilization in the early 1900s.

Actually the autocratic model exists in all shades of gray, rather than the extreme black usually presented. It has been a reasonably effective way of management when there is a “benevolent autocrat” who has a genuine interest in his employees and when the role expectation of employees is autocratic leadership.

Term Paper # 2. The Custodial Model of Organizational Behaviour:

Managers soon recognized that although a compliant employee did not talk back to his boss, he certainly “thought back!” There were many things he wanted to say to his boss, and sometimes he did say them when he quit or lost his temper. The employee inside was a seething mass of insecurity, frustrations, and aggressions toward his boss. Since he could not vent these feelings directly, sometimes he went home and vented them on his wife, family, and neighbours; so the community did not gain much out of his relationship either.

It seemed rather obvious to progressive employers that there ought to be some way to develop employee satisfactions and adjustment during production—and in fact this approach just might cause more productivity! If the employee’s insecurities, frustrations, and aggressions could be dispelled, he might feel more like working. At any rate the employer could sleep better, because his conscience would be clearer.

Development of the custodial model was aided by psychologists, industrial relations specialists, and economists. Psychologists were interested in employee satisfaction and adjustment. They felt that a satisfied employee would be a better employee, and the feeling was so strong that “a happy employee” became a mild obsession in some personnel offices.

The industrial relations specialists and economists favoured the custodial model as a means of building employee security and stability in employment. They gave strong support to a variety of fringe benefits and group plans for security.

The custodial model originally developed in the form of employee welfare programs offered by a few progressive employers, and in its worst form it became known as employer paternalism.

During the depression of the 1930s emphasis changed to economic and social security and then shortly moved toward various labor plans for security and control. During and after World War II, the main focus was on specific fringe benefits. Employers, labour unions, and government developed elaborate programs for overseeing the needs of workers.

A successful custodial approach depends on economic resources, as shown in Table 1. An organization must have economic wealth to provide economic security, pensions, and other fringe benefits. The resulting managerial orientation is toward economic or material rewards, which are designed to make employees respond as economic men. A reciprocal employee orientation tends to develop, emphasizing security.

The custodial approach gradually leads to an organizational dependency by the employee. Rather than being dependent on his boss for his weekly bread, he now depends on large organizations for his security and welfare. Perhaps more accurately stated, an organizational dependency is added atop a reduced personal dependency on his boss.

This approach effectively serves an employee’s maintenance needs, as presented in Herzberg’s motivation maintenance model, but it does not strongly motivate an employee. The result is a passive cooperation by the employee. He is pleased to have his security; but as he grows psychologically, he also seeks more challenge and autonomy.

The natural measure of morale which developed from a custodial model was employee, satisfaction. If the employee was happy, contented, and adjusted to the group, then all was well. The happiness-oriented morale survey became a popular measure of success in many organizations.

Limitations of the Custodial Model:

Since the custodial model is the one which most employers are currently moving away from, its limitations will be further examined. As with the autocratic model, the custodial model exists in various shades of gray, which means that some practices are more successful than others.

In most cases, however, it becomes obvious to all concerned that most employees under custodial conditions do not produce anywhere near their capacities, nor are they motivated to grow to the greater capacities of which they are capable. Though employees may be happy, most of them really do not feel fulfilled or self-actualized.

The custodial model emphasizes economic resources and the security those resources will buy, rather than emphasizing employee performance. The employee becomes psychologically preoccupied with maintaining his security and benefits, rather than with production. As a result, he does not produce much more vigorously than under the old autocratic approach. Security and contentment are necessary for a person, but they are not themselves very strong motivators.

As viewed by William H. Whyte, the employee working under custodialism becomes an “organization man” who belongs to the organization and who has “left home, spiritually as well as physically, to take the vows of organizational life.”

As knowledge of human behaviour advanced, deficiencies in the custodial model became quite evident, and people again started to ask, “Is there a better way?” The search for a better way is not a condemnation of the custodial model as a whole; however, it is a condemnation of the assumption that custodialism is “the final answer”—the one best way to work with people in organizations. An error in reasoning occurs when a person perceives that the custodial model is so desirable that there is no need to move beyond it to something better.

Term Paper # 3. The Supportive Model of Organizational Behaviour:

The supportive model of organizational behaviour has gained currency during recent years as a result of a great deal of behavioural science research as well as favourable employer experience with it.

The supportive model establishes a manager in the primary role of psychological support of his employees at work, rather than in a primary role of economic support (as in the custodial model) or “power over” (as in the autocratic model). A supportive approach was first suggested in the classical experiments of Mayo and Roethlisberger at Western. Electric Company in the 1930s and 1940s.

They showed that a small work group is more productive and satisfied when its members perceive that they are working in a supportive environment. This interpretation was expanded by the work of Edwin A. Fleishman with supervisory “consideration” in the 1940s and that “of Rensis Likert and his associates with the “employee-oriented supervisor” in the 1940s and 1950s.” In fact, the coup de grace to the custodial model’s dominance was administered by Likert’s research which showed that the happy employee is not necessarily the most productive employee.

Likert has expressed the supportive model as the “principle of supportive relationships” in the following words:

“The leadership and other processes of the organization must be such as to ensure a maximum probability that in all interactions and all relationships with the organization each member will, in the light of his background, values, and expectations, view the experience as supportive and one which builds and maintains his sense of personal worth and importance.”

The supportive model, shown in Table 1, depends on leadership instead of power or economic resources. Through leadership, management provides a behavioural climate to help each employee grow and accomplish in the interests of the organization the things of which he is capable (The leader assumes that workers are not by nature passive and resistant to organizational needs, but that they are made so by an inadequate supportive climate at work) They will take responsibility, develop a drive to contribute, and improve themselves, if management will give them half a chance. Management’s orientation, therefore, is to support the employee’s performance.

Since performance is supported, the employee’s orientation is toward it instead of mere obedience and security. He is responding to intrinsic motivations in his job situation. His psychological result is a feeling of participation and task involvement in the organization. When referring to his organization, he may occasionally say “we,” instead of always saying, “they”. Since his higher-order needs are better challenged, he works with more awakened drives than he did under earlier models.

The difference between custodial and supportive models is illustrated by the fact that the morale measure of supportive management is the employee’s level of motivation. This measure is significantly different from the satisfaction and happiness emphasized by the custodial model. An employee who has a supportive leader is motivated to work toward organizational objectives as a means of achieving his own goals. This approach is similar to McGregor’s popular “Theory Y”.

The supportive model is just as applicable to the climate for managers as for operating employees. One study reports that supportive managers usually led to high motivation among their subordinate managers. Among those managers who were low in motivation, only 8 per cent had supportive managers. Their managers were mostly autocratic.

It is not essential for managers to accept every assumption of the supportive model in order to move toward it, because as more is learned about it, views will change. What is essential is that modern managers in business, unions, and government do not become locked into the custodial model. They need to abandon any view that the custodial model is the final answer, so that they will be free to look ahead to improvements which are fitting to their organization in their environment.

The supportive model is only one step upward on the ladder of progress. Though it is just now coming into dominance, some firms which have the proper conditions and managerial competence are already using a collegial model of organizational behaviour, which offers further opportunities for improvement.

Term Paper # 4. The Collegial Model of Organizational Behaviour:

The collegial model is still evolving, but it is beginning to take shape. It has developed from recent behavioural science research, particularly that of Likert, Katz, Kahn, and others at the University of Michigan, Herzberg with regard to maintenance and motivational factors, and the work of a number of people in project management and matrix organization.

(The collegial model readily adapts to the flexible, intellectual environment of scientific and professional organizations). Working in substantially un-programmed activities which require effective teamwork, scientific and professional employees desire the autonomy which a collegial model permits, and they respond to it well.

The collegial model depends on management’s building a feeling of mutual contribution among participants in the organization, as shown in Table 1. Each employee feels that he is contributing something worthwhile and is needed and wanted. He feels that management and others are similarly contributing, so he accepts and respects their roles in the organization. Managers are seen as joint contributors rather than bosses.

The managerial orientation is toward teamwork which will provide an integration of all contributions. Management is more of an integrating power than a commanding power. The employee response to this situation is responsibility. He produces quality work not primarily because management tells him to do so or because the inspector will catch him if he does not, but because he feels inside himself the desire to do so for many reasons.

The employee psychological result, therefore, is self-discipline. Feeling responsible, the employee disciplines himself for team performance in the same way that a football team member disciplines himself in training and in game performance.

In this kind of environment an employee normally should feel some degree of fulfillment and self-realization, although the amount will be modest in some situations. The result is job enthusiasm, because he finds in the job such Herzberg motivators as achievement, growth, intrinsic work fulfillment, and recognition. His morale will be measured by his commitment to his task and his team, because he will see these as instruments for his self-actualization.

Term Paper # 5. Some Conclusions about Models of Organizational Behaviour:

1. The evolving nature of models of organizational behaviour makes it evident that change is the normal condition of these models. As our understanding of human behaviour increases or as new social conditions develop, our organizational behaviour models are also likely to change. It is a grave mistake to assume that one particular model is a “best” model which will endure for the long run.

This mistake was made by some old-time managers about the autocratic model and by some humanists about the custodial model, with the result that they became psychologically locked into these models and had difficulty altering their practices when conditions demanded it.

Eventually the supportive model may also fall to limited use; and as further progress is made, even the collegial model is likely to be surpassed. (There is no permanently “one best model” of organizational behaviour, because what is best depends upon what is known about human behaviour in whatever environment and priority of objectives exist at a particular time.)

2. A second conclusion is that the models of organizational behaviour which have developed seem to be sequentially related to man’s psychological hierarchy of needs. As society has climbed higher on the need hierarchy, new models of organizational behaviour have been developed to serve the higher-order needs that became paramount at the time.

If Maslow’s need hierarchy is used for comparison, the custodial model of organizational behaviour is seen as an effort to serve man’s second-level security needs. It moved one step above the autocratic model which was reasonably serving man’s subsistence needs, but was not effectively meeting his needs for security. Similarly the supportive model is an effort to meet employees’ higher-level needs, such as affiliation and esteem, which the custodial model was unable to serve. The collegial model moves even higher toward service of man’s need for self-actualization.

A number of persons have assumed that emphasis on one model of organizational behaviour was an automatic rejection of other modes (but the comparison with man’s need hierarchy suggests that each model is built upon the accomplishments of the other) For example, adoption of a supportive approach does not mean abandonment of custodial practices which serve necessary employee security needs. What it does mean is that custodial practices are relegated to secondary emphasis, because employees have progressed up their need structure to a condition in which higher needs predominate.

In other words, the supportive model is the appropriate model to use because subsistence and security needs are already reasonably met by a suitable power structure and security system. If a misdirected modern manager should abandon these basic organizational needs, the system would quickly revert to a quest for a workable power structure and security system in order to provide subsistence-maintenance needs for its people.

Each model of organizational behaviour in sense out-modes its predominance by gradually satisfying certain needs, thus opening up other needs which can be better served by a more advanced model. Thus, each new model is built upon the success of its predecessor. The new model simply represents a more sophisticated way of maintaining earlier need satisfactions, while opening up the probability of satisfying still higher needs.

A third conclusion suggests that the present tendency toward more democratic models of organizational behaviour will continue for the longer run. This tendency seems to be required by both the nature of technology and the nature of the need structure. Harbison and Myers, in a classical study of management throughout the industrial world, conclude that advancing industrialization leads to more advanced models of organizational behaviour. Specifically, authoritarian management gives way to more constitutional and democratic-participative models of management.

These developments are inherent in the system; that is, the more democratic models tend to be necessary in order to manage productively an advanced industrial system. Slater and Bennis also conclude that more participative and democratic models of organizational behaviour inherently develop with advancing industrialization. They believe that “democracy is inevitable,” because it is the only system which can successfully cope with changing demands of contemporary civilization in both business and government.

Both sets of authors accurately point out that in modern, complex organizations a top manager cannot be authoritarian in the traditional sense and remain efficient, because he cannot know all that is happening in his organization. He must depend on other centres of power nearer to operating problems.

In addition, educated workers are not readily motivated toward creative and intellectual duties by traditional authoritarian orders. They require high- order need satisfactions which newer models of organizational behaviour provide. Thus, there does appear to be some inherent necessity for more democratic forms of organization in advanced industrial systems.

A fourth and final conclusion is that, though one model may predominate as most appropriate for general use at any point in industrial history, some appropriate uses will remain for other models. Knowledge of human behaviour and skills in applying that knowledge will vary among managers. Role expectations of employees will differ depending upon cultural history. Policies on ways of life will vary among organizations.

Perhaps more important, task conditions will vary. Some jobs may require routine, low-skilled, highly programmed work which will be mostly determined by higher authority and provide mostly material rewards and security (autocratic and custodial conditions). Other jobs will be un-programmed and intellectual, requiring teamwork and self-motivation, and responding best to supportive and collegial conditions. This use of different management practices with people according to the task they are performing is called “management according to task” by Leavitt.

In the final analysis, each manager’s behaviour will be determined by his underlying theory of organizational behaviour, so it is essential for him to understand the different results achieved by different models of organizational behaviour. The model used will vary with the total human and task conditions surrounding the work. The long-run tendency will be toward more supportive and collegial models because they better serve the higher-level needs of employees.

Knowledge management is any structured activity that improves an organization’s capacity to acquire, share and use knowledge in ways that improve its survival and success. The stock of knowledge that resides in an organization is called its intellectual capital, which is the sum of everything that an organization known that given it competitive advantage including its human capital, structural capital, and relationship capital.

Human Capital:

This is the knowledge that employees possess and generate including their skills, experience and creativity.

Structural Capital:

This is the knowledge captured and retained in an organization’s systems and structures. It is the knowledge that remain after all the human capital has gone home.

Relationship Capital:

This is the value derived from an organization’s relationships with customers, suppliers and other external stake holders who provide added value for the organization. For example this includes customer loyalty as well as mutual trust between the organization and its suppliers.

Knowledge Management Processes:

To maintain a valuable stock of knowledge, organizations depend on their capacity to acquire, share and use knowledge more effectively. This process is often called organizational learning because companies must continuously learn about their various environments in order to survive and succeed through adaption. The capacity to acquire, share and use knowledge means that companies have established systems, structures and organizational values that support the knowledge management process.

Knowledge Acquisition:

This includes the process of extracting information and ideas from its environment as well as through insight. One of the fastest and most powerful ways to acquire knowledge is by hiring individuals or acquiring entire companies. Knowledge also enters the organization when employees learn from external sources, such as discovering new resources from suppliers or becoming aware of new trends from clients. A third knowledge acquisition strategy is through experimentation. Companies receive knowledge through insight as a result of search and other creative processes.

Knowledge Sharing:

This process refers to how well knowledge is distributed throughout the organization to those who would benefit from that knowledge. Computer intranets are often marketed as complete “knowledge management” systems.

While somewhat useful in cataloging where knowledge in located, these electronic storage systems can be expensive to maintain, they also overlook the fact that a lot of knowledge is difficult to document. Thus any technological solution needs to be supplemented by giving employees more opportunities for informal online or face to face interaction.

Knowledge Use:

Acquiring and sharing knowledge are wasted exercises unless knowledge is effectively put to use. To do this employees must realize that the knowledge is available and that they have enough freedom to apply it. This requires a culture that supports learning and change.