Here is a term paper on ‘Learning’ for class 11 and 12. Find paragraphs, long and short term papers on ‘Learning’ especially written for college and management students.

Term Paper on Learning

Term Paper Contents:

- Term Paper on the Nature and Definition of Learning

- Term Paper on the Schools of Learning Theory

- Term Paper on the Transfer of Learning

- Term Paper on the Conditions for Learning

- Term Paper on How do we Learn?

- Term Paper on Learning is a Myth or Science

- Term Paper on Shaping Behaviour: A Managerial Tool for Learning

- Term Paper on Learning and Organizational Behaviour

Term Paper # 1. Nature and Definition of Learning:

To understand the processes of learning and development and use this understanding to good effect in developing people and their organizations, you have to be able to think clearly about the concepts you are using. The concepts ‘learning’ and ‘development’ are frequently used interchangeably. The following definitions will enable you to distinguish them and understand the relationship between them.

Learning:

A process within the organism which results in the capacity for changed performance which can be related to experience rather than maturation. It is an experience after which an individual qualitatively changed the way he or she conceived something’.

Learning is a Process:

Not just a cognitive process that involves the assimilation of information in symbolic form, but also an effective and physical process. Our emotions, nerves and muscles are involved in the process, too. It is a process that can be more or less effectively undertaken, and it leads to change, whether positive or negative, for the learner. It can be more effective when we pay it conscious attention.

Development, however, is the process of becoming increasingly complex, more elaborate and differentiated, by virtue of learning and maturation. In an organism, greater complexity, differentiation among the parts, leads to changes in the structure of the whole and to the way in which the whole functions.

In the individual, this greater complexity opens up the potential for new ways of acting and responding to the environment. This leads to the opportunity for even further learning, and so on. Learning, therefore, contributes to development. It is not synonymous with it but development cannot take place without learning.

The outcomes of a person’s learning and development are the way they think, feel and interpret their world (their cognition, affect, attitudes, overall philosophy of life);

The way they see themselves, their self-concept and self-esteem; and their ability to respond to and make their way in their particular environment (their perceptual- motor, intellectual, social, interpersonal skills).

He likens it to a journey that starts from the familiar world and moves through ‘confusion, adventure, great highs and lows, struggle, uncertainty… towards a new world’ in which ‘nothing is different, yet all transformed’; ‘its meaning has profoundly changed’. Learning and development, therefore are significant experiences for individuals and for organizations.

Learning about Learning from Your Own Experience:

All engage in the processes of learning and development, but mostly without paying conscious attention to them and, therefore, not fully understanding them. Will find that you have personal experience of some of the issues it deals with.

Definition of Learning:

What is learning? A psychologist’s definition is considerable broader than the layperson’s view that It’s what we did when we went to school. In actuality, each of us is continuously going to school. “Learning occurs all the time. Therefore, a generally accepted definition of learning is any relatively permanent change in behaviour that occurs as a result of experience. Ironically, we can say that changes in behaviour indicate that learning has taken place and that learning is a change in behaviour”. S. Rabbin

Obviously, the foregoing definition suggests that we shall never see someone “learning”. We can see changes taking place but not the learning itself. The concept is theoretical and, hence, not directly observable.

You have seen people in the process of learning, you have seen people who behave in a particular way as a result of learning and some of you (in fact, I guess the majority of you) have “learned” at some time in your life. In other words, we infer that learning has taken place if an individual behaves, reacts, responds as a result of experience in a manner different from the way he formerly behaved.

Our definition has several components that deserve clarification.

They are:

First, learning involves change. Change may be good or bad from an organizational point of view. People can learn unfavourable behaviours—to hold prejudices or to restrict their output, for example—as well as favourable behaviours.

Second the change must be relatively permanent. Temporary changes may be only reflexive and may not represent learning.

Thirdly our definition is concerned with behaviour. Learning takes place when there is a change in actions. A change in an individual’s thought process or attitudes, if not accompanied by a change in behaviour, would not be learning.

Finally, some form of experience is necessary for learning. Experience may be acquired directly through observation or practice, or it, may be acquired indirectly, as through reading. The crucial test still remains: Does this experience result in a relatively permanent change in behaviour? If the answer is yes, we can say that learning has taken place.

Greenburg and Baron state—“learning is involved in a broad spectrum of organisational behaviours, ranging from developing new vocational skills, to managing employees in ways that foster the greatest productivity”.

Killy defines learning “learning refers to the development and modification of behaviour to get somewhere or do something”.

Term Paper # 2. Schools of Learning Theory:

There are different schools of learning theory—generally learning theories seem to fall into six general schools.

They are:

1. Behaviourist School:

The 1st school is known as the Behaviourist School. Primarily, these theories hold that learning results from the rewards or a punishment that follows a response to a stimulus. These are the so-called S-R Theories.

E.L. Throndike was one of the early researchers into learning. Generally he held that learning was a trial-and-error process. When faced with the need to respond appropriately to a stimulus, the learner tries any and all of his response patterns.

If by chance one works, then that one tends to be repeated and the others neglected. From his research he developed certain laws to further explain the learning process—for example, the Law of Effect: if a connection between a stimulus and response is satisfying to the organism, its strength is increased—if unsatisfying, its strength is reduced.

E.R. Guthrie basically accepted Throndike’s theory, but did not accept the Law of Effect. He came us with an “S-R Contiguity Theory” of learning. His position was that the moment a stimulus was connected to a response—the stimulus would thereafter tend to elicit that response. Thus, if I am learning a poem and learn it sitting down, I can probably recall that poem best when sitting rather than standing. Generally he did not attach much significance to reward and punishment—responses will tend to be repeated simply because they were the last ones made to stimulus.

Clark Hull introduced a new concept—not only was a stimulus and response present in learning—but the organism itself could not be overlooked. The response to a stimulus must take into account the organism and what it is thinking, needing, and feeling at the moment. We now had the S-O-R concept.

B.F. Skinner is usually identified with the Behaviourist School. Rather than construct a theory of learning. He seems to believe that by observation and objective reporting we can discover how organisms learn without the need of a construct to explain the process. He depends heavily upon that is called operant conditioning. He makes a distinction between “Respondent” and “Operant” behaviour. Respondent behaviour is that behaviour caused by a known stimulus, operant behaviour is that behaviour for which we cannot see or identify a stimulus, though one may, and probably does, exist.

If we can anticipate an operant behaviour, and introduce a stimulus when it is evidenced, we can provide the occasion for the behaviour by introducing the stimulus—but the stimulus does not necessarily evoke the behaviour. Thus the emphasis in learning is on correlating a response with reinforcement. This is at the heart of programmed instruction—a correct response is reinforced.

Other researchers have developed variations of the theories described above. Some assume that the organism is relatively passive but the response is.in the repertoire of the learner. Other theorists pay particular attention to instrumental conditioning. They assume that the organism acts on his environment and that the response may not be in his repertoire.

Therefore, it makes sense to identify and reflect upon them so that you’ll then have the ‘hooks’ ready in your mind on to which to hang the information. In the language of a learning theory, you will be ready to decode these new signals.

Berelson and Steiner define learning as “Changes in behaviour that result from previous behaviour in similar situations. Mostly, but by no means always, behaviour also becomes demonstrably more effective and more adaptive after the exercise than it was before. In the broadest terms, then learning refers to the effects of experience, either direct or symbolic on subsequent behaviour.”

Learning would seem to imply these kind of things:

(a) Knowing something intellectually or conceptually one never knew before.

(b) Being able to do something one could not do before—behaviour or skill.

(c) Combining two known into a new understanding of a skill , piece of knowledge, concept, or behaviour.

(d) Being able to use or apply a new combination of skills, knowledge, concept, or behaviour.

(e) Being able to understand and/or apply that which one knows—either skill, knowledge, or behaviour.

Managers are confronted by many factors about which they must make decision:

(a) Desired Outcomes from the Learning Experience:

This can range from complex comprehension of organisational dynamics to simply manual skills. The managers who underwrite training programmes normally stipulate an entirely different set of training outcomes. These usually are identified as reduction of costs; increased productivity; improved morale; and a pool of promotional replacements. Sometimes these are confused by training directors as outcomes of training that are affected by learning theory. It seems to us that these may be results of training but that learning theory does not directly relate to these are outcomes.

(b) Site for Learning:

Training directors are concerned whether learning best occurs on the job; in a classroom; on organizational premises or off organizational premises, university or other formal site; cultural island; or at home.

(c) Learning Methods:

These are on a continuum from casual reading to intense personal involvement in personal-relationship laboratories.

Learning occurs when stimulus is associated with response. From this generalization about how learning occurs a number of specific learning laws, rules or statements are derived. For e.g., repetition of response strengthens its connection with a stimulus and elapse between the stimulus and the response—or the response may be a series of responses that stretch over a period of time. For example, a man may be desirous of marrying a girl but will work for ten years to save enough money to support her adequately before proposing.

2. Gestalt School:

The second grouping is the Gestalt School. These theorists believe that learning is not a simple matter of stimulus and response. They hold that learning is cognitive and involves the whole personality. To them, learning is infinitely more complex than the S-R Theories would indicate. For example, they note that learning may occur simply by thinking about a problem. Kurt Lewin, Wolfgang Kohler, E.C. Tolman and Max Wertheimer are typical theorists in this school. They reject the theory that learning occurs by the building up, bit by bit, of established S-R connections. To them, “the whole is more than the sum of the parts.”

Central in Gestalt theory is the law of ‘Pragnaz’ which indicates the direction of events. According to this law, the psychological organization of the individual tends to move always in one direction, always toward the good Gestalt, an organization of the whole which is regular, simple, and stable.

The law of ‘Pragnaz’ is further a law of equilibrium. According to it, the learning process might be presented as follows: The individual is in a state of equilibrium, of ‘good’ Gestalt. He is confronted by a learning situation. Tensions develop and disequilibrium results.

The individual thus moves away from equilibrium but at the same time he strives to move back to equilibrium. In order to assist this movement back to the regular, simple, stable state, the learning situation should be structured so as to possess a good organization (e.g., simple parts should be presented first; these should lead in an orderly fashion to more difficult parts). The diagram represents the movement towards equilibrium in the learning process.

A third school is the Freudian School. This is a difficult school to capsulize. “It is no simple task to extract a theory of learning from Freud’s writing, for while he was interested in individual development and the kind of re-education that goes on in psychotherapy, the problems whose answers he tried to formulate were not those with which theorists in the field of learning have been chiefly concerned”. Psychoanalytic theory is too complex and, at least at the present time, too little formalized for it to be’ presented as a set of propositions subject to experimental testing.

3. Figure of Equilibrium:

i. The learning situation is presented to the individual.

ii. He moves away from equilibrium.

iii. But attempts to move back to equilibrium.

iv. He organizes the new material in an effort to integrate and systematic it.

v. He moves to equilibrium.

4. Functionalists:

A fourth school is the Functionalists. These seem to take parts of all the theories and view’ learning as a very complex phenomenon that is not explained by either the Gestalt or the Behavioural Theories. Some of the leaders in this school are John Dewey, J.R. Angell, and R.S. Woodworm. These men borrow from all the other schools and are sometimes referred to as “middle of the roaders”.

5. Mathematical Models:

A fifth so-called school are those who subscribe to Mathematical models. To these researchers, learning theories must be stated in mathematical form. Some of these proponents come from different learning theory schools but tend to focus on mathematical models such as Feedback Model, Information—Theory Model, Gaming Model, Different Calculus Model, Stochastic Model, and the Statistical Association Model. As one tries to understand this school, it occurs to one that they seem to have to theory of their own but are expressing research findings of other theorists in mathematical terms.

6. Current Learning Theory Schools:

A sixth school is more general in nature and can best be characterized by calling it Current Learning Theory Schools. These are quite difficult to classify and seem to run the range of modifying Gestalt Theories, modifying Behavioural theories, accommodating two pieces of both theories, assuming that training involves the whole man— psychological, physiological, biological, and neurophysiological. Some of these are the Postulate System of MacCorquodale and Meehl and the Social Learning Theory of Rotter.

Current Research:

Some of the more exciting kinds of current research seem to be in the neurophysiological interpretations of learning. One example of this was shown on a national television program, “Way out Men.” February 13, 1965. In this research, flatworms are trained to stay within a white path.

If they deviate from the white path, they receive an electrical shock. After the flatworms learn to stay within the prescribed path, they are then chopped up and fed to a control group of worms. This control group learns to stay within the white path in about half the learning time. This has led come theorists to talk about the possibility of eventually feeding students “professor Burgers”.

Additional research is going on in this area and we have recently seen two or three other related pieces of research. It seems to indicate a key as to where memory and instincts are stored so that they can be transmitted to offering. One is intrigued by this research when one remembers popular beliefs such as “Eating of the Tree of Knowledge”, eating fish is good brain food, and the practice of cannibals eating the brain of an educated man to become smart or to eat the heart of a brave man to become courageous.

Term Paper # 3. Transfer of Learning:

One of the problems that often confront a training director is the transfer of learning.

Some of the major ways in which learning theories attempt to provide for the transfer of that which is learned to the work situation are the following:

1. Actually doing the “that” which is being learned. In this instance, we believe transfer is best when learning occurs on or in live situations. This is so because little or no transfer is needed—what is learned is directly applied. Instances employing this technique are on-the-job training, coaching, apprenticeship, and job experience.

2. Doing something that is similar to that which is to be learned. This transfer principle is applied when we use simulated experiences—the training experience and techniques are as similar to the job as, possible. Sometimes we let the trainee discover the principles and apply then to his job. In other instances, particularly in skill training, he works on mockups which closely resemble the actual equipment on which he will work. Other techniques would include role playing, sensitivity training and case studies.

3. Reading or hearing about that which is to be learned. The trainee must now figure out the ways in which he has heard or read applies to his job and how he can use it. Illustrative training techniques would be lecturers, reading, and most management and supervisory training programs featuring the “telling” method.

4. Doing or reading about anything on the assumption it will help anything to be learned. In this instance there is an assumption that a liberalized education makes the trainee more effective in whatever job he occupies or task he is to learn. This might be termed the liberal arts approach. It assumes that a well-rounded, educated person is ‘more effective, and more easily trained in specifies, if he understands himself, his society, his world, and other disciplines. Obviously, this would be a somewhat costly way of training. It would involve perceptual living and generalized education.

Most research has gone into the transfer of learning. Most of this occurs in the S-R Theories. It seems to be less of a problem in the other major theories. This is quite understandable as one compares the theories of learning. For example, the S-R Theories become quite concerned with questions like “Will the study of mathematics help a person learnings foreign language easier and more quickly?” This has led to much research regarding the conditions under which the transfer of learning best occurs. It is also applicable to conceptual learning. For example, will learning how to delegate responsibilities to children be useful in the delegation process in the work organization?

Term Paper # 4. Conditions for Learning:

The concerns about motivating individuals to learn, and the recognition that there is such a thing as learning process. Numerous lists of conditions for learning exist. They vary depending on the learning theory schools. However, there is a remarkable acceptance of some general conditions that should exist for learning regardless of the learning theory employed.

One of these composite lists follows:

1. Acceptance that all human beings can learn. The assumption, for example, that you “cannot teach an old dog new tricks” is wrong. Few normal people at any age are probably incapable of learning. The tremendous surge in adult education and second careers after retirement attest to people’s ability to learn at all ages.

2. The individual must be motivated to learn. This motivation should be related to the individual’s drives.

(a) The individual must be aware of the inadequacy of unsatisfactoriness of his present skill, behaviour, or knowledge.

(b) The individual must have a clear picture of the behaviour which he is required to adopt.

3. Learning is an active process, not passive. It takes action and involvement by and of the individual with resource persons and the training group.

4. Normally, the learner must have guidance. Trial and error are too time consuming. This is the process of feedback. The learner must have data on “how am I doing” if he is to correct improper performance before it becomes patronized.

5. Appropriate materials for sequential learning must be provided: cases; problems discussion, reading. The trainer must possess a vast repertoire of training tools and materials and recognize the limitations and capacities of each. It is in this area that so many training directors get trapped by utilizing the latest training fads or gimmicks for inappropriate learning.

6. Time must be provided to practice the learning; to internalize to give confidence. Too often trainers are under pressure to “pack the program”—to utilize every moment available to “tell them something”. This is inefficient use of learning time. Part of the learning process requires sizable pieces of time for assimilation, testing, and acceptance.

7. Learning Methods if possible should be varied to avoid boredom. It is assumed that the trainer will be sufficiently sophisticated to vary the methods according to their usefulness to the material being learned. Where several methods are about equally useful, variety should be introduced to offset factors of fatigue and boredom.

8. The learner must secure satisfaction from the learning. This is the old story of “you can lead a horse to water…” Learners are capable of excellent learning under the most trying conditions if the learning is satisfying to one or more of their needs. Conversely, the best appointed of learning facilities and trainee comfort can fail if the program is not seen as useful by the learner.

9. The learner must get reinforcement of the correct behaviour. B.F. Skinner and the Behaviourists have much to say on this score. Usually, learners need fairly immediate reinforcement. Few learners can wait for months for correct behaviour to be rewarded. However, there may well be long-range rewards and lesser-intermediate rewards. We would also emphasize that awarded job performance when the learner training returns from the program must be consistent with the learning program rewards.

10. Standards of performance should be set for the learner. Set goals for achievement. While learning is quite individual, and it is recognized that learners will advance at differing paces, most learners like to have bench marks by which to judge their progress.

11. Recognition that there are different levels of learning and that these take different times and methods. Learning to memorize a simple poem is entirely different from learning long-range planning. There are, at least four identifiable levels of learning; each requiring different timing, methods, involvement, techniques, and learning theory.

At the simplest level we have the skills of motor responses, memorization, and simple conditioning. Next, we have the adaptation level where we are gaining knowledge or adapting to a simple environment. Learning to operate an electric typewriter after using a manual typewriter is an example.

Third, is the complex level, utilized when we train in interpersonal understandings and skill, look for principles in complex practices and action, or try to find integrated meaning in the operation of seemingly isolated parts.

At the most complex level we deal with the values of individuals and group. This is a most subtle, time-consuming, and sophisticated training endeavor. Few work organizations have training programs with value change of long-standing, cultural or ethnic values as their specific goal. Many work organizations, however, do have training programs aimed at changing less entrenched values.

The reader will recognize that this listing of conditions under which people learn contains concepts and principles from most of the learning theory schools. Most training directors are generalists, and seldom do their training programs focus on a constant single-objective outcome.

It is perhaps inevitable that his own guiding training concepts and principles will be a meld from many theories. It is important however, that he understand the theories of learning so that he is using those concepts and principles which can best assure he will accomplish his organizations training objectives in specific training programs.

It is encouraging to note that some social scientists are aware of this breach between research and practice:

“…………….. Knowledge is not practice and practice is not knowledge. The improvement of one does not lead automatically to the improvement of the other. Each can work fruitfully for the advancement of the other, but also, unfortunately, each can develop separately from the other and hence stuntedly in relation to the other”?

“It should be clear that the linking of social theory to social practice, as well as the development of a practice-linked theory of the application of social science knowledge to practice, is an intellectual challenge of the first magnitude. But is one that many social scientists— particularly those who rarely leave the university system—have neglected.”

“Lewin is credited with remarking that one can bridge the gap between theory and reality only if one can tolerate “constant intense tension”. Roethlisberger and his colleagues described these tensions all too well for the person trying to improve the practice of administration.

In relating learning theory to learning goals, learning theory corollaries, and the designed learning experience or training program.

Two points are critical:

i. Learning goal and

ii. Designing the programme.

Term Paper # 5. How do we Learn?

Three theories have been offered to explain the process by which we acquire patterns of behaviour. These are classical conditioning, operant conditioning, and social learning. Classical conditioning grew out of experiments to teach dogs to salivate in response to the ringing of a bell, conducted at the turn of the century by Russian physiologist Ivan Pavlov a simple surgical procedure allowed Pavlov to measure accurately the amount of saliva secreted by a dog.

When Pavlov presented the dog with a piece of meat, the dog exhibited a noticeable increase in salivation. When Pavlov withheld the presentation of meat and merely rang a bell, the dog did not salivate.

Then Pavlov proceeded to link the meat and the ringing of the bell. After repeatedly hearing the bell before getting the food, the dog began to salivate as soon as the bell rang. After a while, the dog would salivate merely at the sound of the bell, even if no food was offered. In effect, the dog had learned to respond—that is, to salivate—to the bell. Let’s review this experiment to introduce the key concepts in classical conditioning.

The meat was an unconditioned stimulus; it invariably caused the dog to react in a specific way. The reaction that took place whenever the unconditioned stimulus occurred was called the unconditioned response (or the noticeable increase in salivation, in this case).

The bell was an artificial stimulus, or what we call the conditioned stimulus. Although it was originally neutral, after the bell was paired with the meat (an unconditioned stimulus), it eventually produced a response when presented alone. The last key concept is the conditioned response. This describes the behavior of the dog; it salivated in reaction to the bell alone.

Using these concepts, we can summarize classical conditioning. Essentially, learning a conditioned response involves building tip an association between a conditioned stimulus and an unconditioned stimulus. When the stimuli, one compelling and the other one neutral, are paired, the neutral one becomes a conditioned stimulus and, hence, takes on the properties of the unconditioned stimulus.

Classical conditioning can be used to explain why Christmas carols often bring back pleasant memories of childhood; the songs are associated with the festive Christmas spirit and evoke fond memories and feelings of euphoria. In an organizational setting, we can also see classical conditioning operating. For example, at one manufacturing plant, every time the top executives from the head office were scheduled to make a visit, the plant management would clean up the administrative offices and wash the windows.

This went on for years. Eventually, employees would turn on their best behaviour and look prim and proper whenever the windows were cleaned—even in those occasional instances when the cleaning was not paired with the visit from the top brass. People had learned to associate the cleaning of the windows with a visit from the head office.

Classical conditioning is passive. Something happens and we react in a specific way. It is elicited in response to a specific, identifiable event. As such, it can explain simple reflexive behaviours. But most behaviour—particularly the complex behaviour of individuals in organizations—is emitted rather than elicited.

It is voluntary rather than reflexive. For example, employees choose to arrive at work on time, ask their boss for help with problems, or “goof off” when no one is watching. The learning of those behaviours is better understood by looking at operant conditioning.

Operant Conditioning:

Argues that behaviour is a function of its consequences. People learn to behave to get something they want or to avoid something they don’t want. Operant behaviour means voluntary or learned behaviour in contrast to reflexive or unlearned behaviour.

The tendency to repeat such behaviour is influenced by the reinforcement or lack of reinforcement brought about by the consequences of the behaviour. Therefore, reinforcement strengthens a behaviour and increases the likelihood that it will be repeated.

What Pavlov did for classical conditioning, the Harvard psychologist B. F. Skinner did for operant conditioning. Building on earlier work in the field, Skinner’s research extensively expanded our knowledge of operant conditioning. Even his staunchest critics, who represent a sizeable group, admit that his operant concepts work.

Behaviour is assumed to be determined from without—that is, learned—rather than from within—reflexive, or unlearned. Skinner argued that creating pleasing consequences to follow specific forms of behaviour would increase the frequency of that behaviour. People will most likely engage in desired behaviours if they are positively reinforced for doing so. Rewards are most effective if they immediately follow the desired response. In addition, behaviour that is not rewarded, or is punished, is less likely to be repeated.

You see illustrations of operant conditioning everywhere. For example, any situation in which it is either explicitly stated or implicitly suggested that reinforcements are contingent on some action on your part involves the use of operant learning. Your instructor says that if you want a high grade in the course you must supply correct answers on the test.

A commissioned sales person wanting to earn a sizeable income finds that doing so is contingent on generating high sales in her territory. Of course, the linkage can also work to teach the individual to engage in behaviours that work against the best interests of the organization. Assume that your boss tells you that if you will work overtime during the next three-week busy season, you will be compensated for it at the next performance appraisal. However, when performance appraisal time comes, you find that you are given no positive reinforcement for your overtime work.

The next time your boss asks you to work overtime, what will you do? You’ 11 probably decline! Your behavior can be explained by operant conditioning. If a behaviour fails to be positively reinforced, the probability that the behavior will be repeated declines.

Social Learning:

Individuals can also learn by observing what happens to other people and just by being told about something, as well as by direct experiences. So, for example, much of what we have learned comes from watching models—parents, teachers, peers, motion picture and television performers, bosses, and so forth. This view that we can learn through both observation and direct experience has been called social-learning theory.’

Although social-learning theory is an extension of operant conditioning— that is, it assumes that behaviour is a function of consequences—it also acknowledges the existence of observational learning and the importance of perception in learning. People respond to how they perceive and define consequences, not to the objective consequences themselves.

The influence of models is central to the social-learning viewpoint. Four processes have been found to determine the influence that a model will have on an individual.

The inclusion of the following processes when management sets up employee-training programs will significantly improve the likelihood that the programs will be successful:

1. Attentional Processes:

People learn from a model only when they recognize and pay attention to its critical features. We tend to be most influenced by models that are attractive, repeatedly available, important to us, or similar to us in our estimation.

2. Retention Processes:

A model’s influence will depend on how well the individual remembers the model’s action after the model is no longer readily available. Part Two The Individual.

Term Paper # 6. Learning is a Myth or Science:

“You can’t teach an old dog new tricks”

This statement is false. It reflects the widely held stereotype that older workers, have difficulties in adapting to new methods and techniques. Studies consistently demonstrate that older employees are perceived as being relatively inflexible, resistant to change, and less trainable than their younger counterparts, particularly with respect to information technology skills. But these perceptions are wrong.

The evidence indicates that older workers (typically defined as people aged SO and Over) want to learn and are just as capable of learning as any other employee group. Older workers do seem to be somewhat less efficient in acquiring complex or demanding skills. That is, they may take longer to train. But once trained, they perform at levels comparable to those of younger workers.

The ability to acquire the skills, knowledge, or behavior necessary to perform a job at a given level—that is, trainability—has been the subject of much research. And the evidence indicates that there are differences between people in their trainability. A number of individual- difference factors (such as ability, motivational level, and personality) have been found to significantly influence learning and training outcomes. However, age has not been found to influence these outcomes.

3. Motor Reproduction Processes:

After a person has seen a new behaviour by observing the model, the watching must be converted to doing. This process then demonstrates that the individual can perform the modeled activities.

4. Reinforcement Processes:

Individuals will be motivated to exhibit the modeled behavior if positive incentives or rewards are provided. Behaviours that are positively reinforced will be given more attention, learned better, and performed more often.

Term Paper # 7. Shaping Behaviour: A Managerial Tool for Learning:

Because learning takes place on the job as well as prior to it, managers will be concerned with how they can teach employees to behave in ways that most benefit the organization. When we attempt to mould individuals by guiding their learning in graduated steps, we are shaping behaviour.

Consider the situation in which an employee’s behaviour is significantly different from that sought by management. If management rewarded the individual only when he or she showed desirable responses, there might be very little reinforcement taking place. In such a case, shaping offers a logical approach toward achieving the desired behaviour.

We shape behaviour by systematically reinforcing each successive step that moves the individual closer to the desired response. If an employee who has chronically been a half-hour late for work comes in only 20 minutes late, we can reinforce that improvement. Reinforcement would increase as responses more closely approximated the desired behaviour.

Methods of Shaping Behaviour:

There are four ways in which to shape behaviour:

i. Through positive reinforcement,

ii. Negative reinforcement,

iii. Punishment, and

iv. Extinction.

Following a response with something pleasant is called positive reinforcement. This would describe, for instance, the boss who praises an employee for a job well done. Following a response by the termination or withdrawal of something unpleasant is called negative reinforcement. If your college instructor asks a question and you do not know the answer, looking through your lecture notes is likely to preclude your being called on.

This is a negative reinforcement, because you have learned that looking busily through your notes prevents the instructor from calling on you. Punishment is causing an unpleasant condition in an attempt to eliminate an undesirable behaviour. Giving an employee a two-day suspension from work without pay for showing up drunk is an example of punishment.

Eliminating any reinforcement, it tends to be gradually extinguished. College instructors who wish to discourage students from asking questions in class can eliminate this behaviour in their students by ignoring those who raise their hands to ask questions. Hand-raising will become extinct when it is invariably meet with an absence of reinforcement.

Both positive and negative reinforcement result in learning. They strengthen a response and increase the probability of repetition. In the preceding illustrations, praise strengthens and increases the behaviour of doing a good job because praise is desired.

The behaviour of “looking busy” is similarly strengthened and increased by its terminating the undesirable consequence of being called on by the teacher. However, both punishment and extinction weaken behaviour and tend to decrease its subsequent frequency.

Reinforcement, whether it is positive or negative, has an impressive record as a shaping tool. Our interest, therefore, is in reinforcement rather than in punishment or extension.

A review of research findings on the impact of reinforcement upon behaviour in organizations concluded that:

1. Some type of reinforcement is necessary to produce a change in behaviour.

2. Some types of rewards are more effective than others for use in organizations.

3. The speed with which learning takes place and the permanence of its effects will be determined by the timing of reinforcement.

Point 3 is extremely important and deserves considerable elaboration.

Reinforcement Schedules and Behaviour:

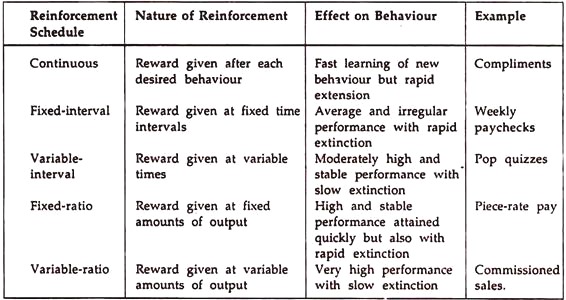

Continuous reinforcement schedules can lead to early satiation, and under this schedule behaviour tends to weaken rapidly when reinforcers are withheld. However, continuous reinforcers are appropriate for newly emitted, unstable, or low-frequency responses. In contrast, intermittent reinforcers preclude early satiation because they don’t follow every response. They are appropriate for stable or high-frequency responses.

In general, variable schedules tend to lead to higher performance than fixed schedules. For example, most employees in organizations are paid on fixed-interval schedules. But such a schedule does not clearly link performance and rewards.

The reward is given for time spent on the job rather than for a specific response (performance). In contrast, variable-interval schedules generate high rates of response and more stable and consistent behaviour because of a high correlation between performance and reward and because of the uncertainty involved—the employee tends to be more alert because there is a surprise factor.

Behaviour Modification:

There is a now-classic study that took place a number of years ago with freight packers at Emery Air Freight (now part of FedEx). Emery’s management wanted packers to use freight containers for shipments whenever possible because of specific economic savings.

When packers were asked about the percentage of shipments contained, the standard reply was 90 percent. An analysis by Emery found, however, that the actual container utilization rate was only 45 percent. In order to encourage employees to use containers, management established a program of feedback and positive reinforcements. Each packer was instructed to keep a checklist of his or her daily packing’s, both containerized and non-containerized.

At the end of each day, the packer computed his or her container utilization rate. Almost unbelievably, container utilization jumped to more than 90 percent on the first day of the program and held at that level. Emery reported that this simple program of feedback and positive reinforcements saved the company $2 million over a three-year period.

This program at Emery Air Freight illustrates the use of behaviour modification, or what has become more popularly called OB Mod. It represents the application of reinforcement concepts to individuals in the work setting.

The typical OB Mod program follows a five-step problem solving model:

(1) Identifying critical behaviours;

(2) Developing baseline data;

(3) Identifying behavioural consequences;

(4) Developing and implementing an intervention strategy; and

(5) Evaluating performance improvement.

Everything an employee does on his or her job is not equally important in terms of performance outcomes. The first step in OB Mod, therefore, is to identify the critical behaviours that make a significant impact on the employee’s job performance.

These are those 5 to 10 percent of behaviours that may account for up to 70 or 80 percent of each employee’s performance. Using containers whenever possible by freight packers at Emery Air Freight is an example of a critical behaviour.

The second step requires the manager to develop some baseline performance data. This is obtained by determining the number of times the identified behaviour is occurring under present conditions. In our freight packing example at Emery, this would have revealed that 45 percent of all shipments were containerized.

The third step is to perform a functional analysis to identify the behavioural contingencies or consequences of performance. This tells the manager the antecedent cues that emit the behaviour and the consequences that are currently maintaining it. At Emery Air Freight, social norms and the greater difficulty in packing containers were the antecedent cues.

This encouraged the practice of packing items separately. Moreover, the consequences for continuing the behaviour, prior to the OB Mod intervention, were social acceptance and escaping more demanding work. Once the functional analysis is complete, the manager is ready to develop and implement an intervention strategy to strengthen desirable performance behaviours and weaken undesirable behaviours.

The appropriate strategy will entail changing some elements of the performance- reward linkage—structure, processes, technology, groups, or the task—with the goal of making high-level performance more rewarding.

In the Emery example, the work technology was altered to require the keeping of a checklist. The checklist plus the computation, at the end of the day, of a container utilization rate acted to reinforce the desirable behaviour of using containers.

The final step in OB Mod is to evaluate performance improvement. In the Emery intervention, the immediate improvement in the container utilization rate demonstrated that behavioural change took place. That it rose to 90 percent and held at that level further indicates that learning took place. That is, the employees underwent a relatively permanent change in behaviour.

OB Mod has been used by a number of organizations to improve employee productivity, to reduce errors, absenteeism, tardiness, accident rates, and to improve friendliness toward customers. 45 For instance, a clothing manufacturer saved $60,000 in one year from fewer absences.

A packing firm improved productivity 16 percent, cut errors by 40 percent, and reduced accidents by more than 43 percent—resulting in savings of over $1 million. A bank successfully used OB Mod to increase the friendliness of its tellers, which led to a demonstrable improvement in customer satisfaction.

Term Paper # 8. Learning and Organizational Behaviour:

Some Specific Organizational Applications:

We have alluded to a number of situations in which learning theory could be helpful to managers.

We will briefly look at four specific applications:

1. Substituting skill based pay,

2. Employees Disciplining,

3. Developing effective employee training programs, and

4. Applying learning theory to self-management.

1. Skill-Based Pay—An Innovative Reward System:

Most organizations provide their salaried employees incentives based on good performance. But, ironically, organizations with paid sick leave programs experience almost twice the absenteeism of organizations without such programs.

The reality is that sick leave programs reinforce the wrong behaviour—absence from work. When employees receive 10 paid sick days a year, it’s the unusual employee who isn’t sure to use them all up, regardless of whether he or she is sick. Organizations should reward attendance not absence.

2. Employee Discipline:

The process of systematically administering punishment, learning encourages desirable behaviour and discourage undesirable behaviour. Managers will respond with disciplinary actions such as oral reprimands, written warnings, and temporary suspensions. But our knowledge about punishment’s effect on behaviour indicates that the use of discipline carries costs. It may provide only a short-term solution and result in serious side effects.

Disciplining employees for undesirable behaviours tells them only what not to do. It doesn’t tell them what alternative behaviours are preferred. The result is that this form of punishment frequently leads to only short-term suppression of the undesirable behaviour rather than its elimination. Continued use of punishment, rather than positive reinforcement, also tends to produce a fear of the manager.

As the punishing agent, the manager becomes associated in the employee’s mind with adverse consequences. Employees respond by “hiding” from their boss. Hence, the use of punishment can undermine manager-employee relations.

Discipline does have a place in organizations. In practice, it tends to be popular because of its ability to produce fast results in the short run. Moreover, managers are reinforced for using discipline because it produces an immediate change in the employee’s behaviour.

3. Developing Training Programs:

Most organizations have some type of systematic training program. More specifically, U.S. corporations with 100 or more employees spent in excess of $58 billion in one recent year on formal training for 47.3 million workers. Can these organizations draw from our discussion of learning in order to improve the effectiveness of their training programs? Certainly.

Social-learning theory offers such a guide. It tells us that training should offer a model to grab the trainee’s attention; provide motivational properties; help the trainee to file away what he or she has learned for later use; provide opportunities to practice new behaviours; offer positive rewards for accomplishments; and, if the training has taken place off the job, allow the trainee some opportunity to transfer what he or she?

4. Self-Management:

Organizational applications of learning concepts are not restricted to managing the behaviour of others. These concepts can also be used to allow individuals to manage their own behaviour and, in doing so, reduce the need for managerial control. This is called ‘self-management.’

Self-management requires an individual to deliberately manipulate stimuli, internal processes, and responses to achieve personal behavioral outcomes. The basic processes involve observing one’s own behaviour, comparing the behavior with a standard, and rewarding oneself if the behaviour meets the standard. Knowledge management—the process of gathering, organizing, and sharing a company’s information and knowledge assets. Knowledge management, programs involve using technology to establish data bases and retrieval systems.

So, how might self-management be applied? Here’s an illustration. A group of state government blue-collar employees received eight hours of training in which they were taught self-management skills. They were then shown how the skills could be used for improving job attendance? They were instructed on how to set specific goals for job attendance, in both the short and intermediate term.

They learned how to write a behavioural contract with themselves and to identify self-chosen reinforcers. Finally, they learned the importance of self-monitoring their attendance behaviour and administering incentives when they achieved their goals. The net result for these participants was a significant improvement in job attendance.

Attitude:

An attitude is an individual’s predisposition to think, feel, perceive and behave in certain ways toward a particular tangible or intangible phenomenon. (Pierce and Dardner). Organizational attitude reflects on the treatment towards employees, policies, objectives and culture. It would be a formidable task to review all of the work attitudes formed in the work place.

Laurie Mullius openies that there are no limits to the attitude people hold. Attitudes are learned throughout life and are embodied within our socialisation process.

Attitudes can be distinguished from beliefs and values:

Attitudes can be defined as providing a state of ‘readiness’ or tendency to respond in a particular way. Beliefs are concerned with what is known about the world, they centre on what is on reality as it is understood. Value are concerned with what ‘should’ be and what is desirable. Hofstede defines values as a broad tendency to prefer certain states of affairs over others.

Hellriegel of Slocum draws links between attitudes of behaviour. Attitudes are another type of individual difference that affects behaviour.Attitudes are relatively lasting feelings, beliefs, of behavioural tendencies aimed of specific people, groups, ideas, or objects.

Link to Behaviour:

To what extent do attitudes predict of cause behaviour is not simple to explain.

Pollsters and others often measure attitudes and attempt to predict subsequent behaviour.

Three principles can improve the accuracy of predicting behaviour from attitudes:

1. General attitudes best predict general behaviours.

2. Specific attitudes best predict specific behaviours.

3. The less time that elopsy between attitude measurement of behaviour, the move consistent will be the relationship between attitude and behaviour.

One of the things that has been found to affect the link between an attitude and behaviour is hope.

Hope involves a person’s mental will power (determination) and way power (road map) to achieve goals: Simply wishing for something is not enough, a person must have the means to make it happen. However, all the knowledge of skills needed to solve a problem won’t help if the person does not have the willpower to do so.

Katz has suggested that attitudes and motives are interlinked. Attitudes can serve four main functions:

1. Knowledge:

Provides a basis for the interpretation and classification of new information. Attitudes provide a knowledge base and framework within which new information can be placed.

2. Expressive:

Attitudes become a means of expression, instrumental—attitudes maximise rewards and minimise sanctions. Behaviour or knowledge which has resulted in the satisfaction of needs is thus move likely to resulted in a favourable attitudes.

3. Ego-Defensive:

Attitudes may be held in order to protect the ego from an undesirable truth or reality. It seems that we do not always behave in a way that is true to our beliefs; what we say and what we do may be very different. That is why attitudes can be revealed not only in behaviour but also by the individual’s thoughts and by feelings.

Following findings have important implication for the study of attitudes:

i. Attitudes cannot be seen; they can only be inferred.

ii. Attitudes are often saved within organizations and as such are embodied in the culture of organizations. Attitudes in inherent within wider society reinforced or reshaped by the organization.

4. Attitude Change:

Attitudes rarely change but may easily change with new information or experiences. Attitude change stress the importance of balance and consistency in our psyche. In conflicting attitudes, we try to change one of the attitudes to reach a balanced state. Cognitive dissonance is the term given to the discomfort felt when we act in a way that is inconsistent with our true beliefs.

Considerable research has demonstrated the importance of the following variables in a programme of attitude change:

The persuade’s characteristics

Presentation of issues

Audience characteristics

Group influences

Outcome of attitude change

(Reward and punishment).

Cognitive Component:

The cognitive component of an attitude is what we know, or think we know, about the attitude object. It consists of information, facts, statistics, data, and so on, that we believe to be true about the attitude object. We may in fact be, incorrect, but we think it is true. The cognitive component of the attitude “Bill Gates is very successful businessman” is “successful”; the attitude object is Bill Gates. The cognitive component (is successful) is associated with the attitude object (Bill Gates).

Affective Component:

The affective components of an attitude consist of the feelings we have toward an attitude objects. This involves evaluation and emotion and is often expressed as like or dislike. Affective components can range from disgust, to indifference, to adoration, and differ from cognitive component in that they involve intensity of feeling, and often a wide range of it. Cognitive components are neutral statements of the facts. One way to distinguish between the two is to remember the old saying “just tell me the facts”.

The affective component of an attitude is really our reaction to the cognitive component. As such, the particular pattern of beliefs we hold about a person or thing (the cognitive component) exerts a major influence on our feelings toward that object. However, we use different evaluative processes as we react to our beliefs, because of different values, motivations, perceptions, and so on.

Thus, people can have very different affective attitude components even though they possess similar cognitive component. Two students agree that their professor is knowledgeable. Yet, one likes the professor (eager to share her knowledge) while the other student dislikes the professor (hates “know -it-alls”).

Behavioural Tendency Component:

The final component of attitude is the behavioural tendency component. This is the way we’re inclined to behave toward an attitude object, that is, how the object “makes” us want to behave. Behavioural intentions strong predictors of future behaviour.

It is this component that draws researchers to study of attitudes. If attitudes didn’t eventually translate into behaviour, they would be of much less consequence to organizations. Researchers assess employee attitudes, and then attempt to predict how the employees will behave on the basis of that assessment.

Both cognitive and affective components of attitudes influence the way people behave towards an attitude object. However, many different behavioural tendencies are possible depending on the particular pattern of cognitive and affective attitude components. One may ultimately attend all regularly while the other the student shows up only on examination dates.

As we all know, the attitudes people hold are complex, contradictory and often counterintuitive, to name a few reasons why they are always not easy to sort out. If we try to sort out an attitude by its components, we must remember that attitudes have three components, each of which affects the others. Let’s take persons attitudes toward the company they work for.

The cognitive component might include information about the size of the organization, the age of his or her manager, and the amount of money the worker believes a coworker earns. The affective component could include the worker’s dislike of the organization’s small size, concern that the manager is too young. To exercise authority and unhappiness that a co-worker is paid more.

The behavioral tendency component could range from an intension to leave a small company. For a larger one to ask to be reassigned to an older manager, or to request a pay rise. These are quite a few items to ponder.

Attitude Formation:

We are born with our attitudes. Instead, our attitudes develop through the experiences that we have with attitude objects (for example, pay, supervision, work). There are four major sources of such experiences and thus of our attitudes: personal experiences, association, social learning and heredity.

Personal Experiences:

Personal experiences means that we have come in direct contact with the attitude objects. Through this encounter, we perceive certain characteristics of traits of the attitude objects.

Some of these perceptions are transformed into our attitude about the object. Persona experiences usually have their first impact on the cognitive component.

From their first experiences on the job, new employees might form these cognitive components of their attitude towards the company:

i. There are many employees at this company.

ii. My job is very difficult.

iii. My supervisor is not busy as I am.

iv. My co-workers complain a lot.

Remember that giving the same situation, two people may or may not form the same cognitive component. One may ignore certain factors that the other finds important. Even given the same cognitive components (the once just listed, for example), two people may use them to form entirely different affective components.

Thus, one new hire may conclude “I like having lots of people around, I like the challenges of my duties, I am grateful my supervisor has time to check my work, I don’t understand why my co-workers are not satisfied”.

Another new hire, giving the same cognitive components, might conclude “I feel paranoid around so many people, I did not expect to work so hard at my first job I think it’s disgusting that I have got more to do then my supervisor, I am going to take another job that moment something better turns up”.

Association:

When we “transfer” parts or all of our attitude about an old attitude object to a new one, association is forming the new attitude. Two attitude object can be associated in a variety of ways. Perhaps you notice that a new employee, rail, spending a lot of time with Jon, a coworker who is components and whom you like personally.

To the degree that you associate rail and Jon, your attitude towards rail will include competence and liking. Two attitude objects can be associated for a variety of reasons. Anything that causes you to associate two attitude objects creates the possibility that you will transfer your attitude from the first to the second.

These transfers may be accurate, frequently, they are not. If your attitude toward one supervisor is favourable, you may generalize that attitude to a future supervisor because of association. Personal experiences, however, may cause you to revise your attitude if you find that the new supervisor behaves quite differently from your previous supervisor.

Social Learning:

A very common and powerful source of attitude formation comes from social learning. Social learning of attitude occurs when people we work with influence our attitudes. We often form attitudes towards objects we have not personally experienced; instead, we take up the attitude of someone we trust that has experience with the object.

The attitudes of others can override our predisposition to form attitude by association. In short our beliefs are frequently molded by others. All too often, however, the cognitive components shared by others are not accurate since we have no direct experience with the attitude object, we can’t always evaluate the accuracy of the information.

Social learning affects not only beliefs but affective reaction and behavioural tendencies as well. Many people believe that Harvard student are rich, spoiled, pompous, self-centred individuals who are not they think they are, who take advantage of their employers, and who exploit co-worker but how many of us have ever met a Harvard student?

Heredity:

Heredity is the transmission from parents to offspring of certain defining characteristics. A genetic predisposition is an inherited propensity to behave or think in certain ways. Our intelligence is due in large part to the genes we inherit.

The environment were raised is also affecting our intelligence, although researchers disagree on the extend its influence. Heredity plays a part in our tendencies to develop certain type of attitudes.

Some people genetically programmed to have positive (or negative) attitude towards certain classes of objects recent research suggests that up to 30% of the attitude we possess, especially that affective component may have a genetic component. Still, the other determinants of attitude combine to have a far stronger influence.