Here is a term paper on the ‘Determinants of Organizational Design’ for class 11 and 12. Find paragraphs, long and short term papers on the ‘Determinants of Organizational Design’ especially written for college and management students.

Term Paper # 1. Environment as a Determinant of Organizational Design:

One of the most obvious determinants of organizational design is, of course environment in which the organization operates. The external environment subject the organization to a complex set of forces. The environmental influences organization are diverse in nature and include the competitors/suppliers consumers, trade unions, technological breakthroughs, governmental regulation etc. These affect the organization both directly and indirectly.

The entry competitor in the market would directly affect the organization, while it may be indirectly influenced by the changes in the socio-political environment example, the reunification of Germany and the opening of the European in the 1990’s created new opportunities for exports for many Indian compare.

The open systems view of the organization in that the effectiveness of the organization would largely depend on its ability to develop mechanisms for coping with these environmental influence. Organisations sometimes deal with such environmental demands the non-structural means, such as advertising, public relations or changes organizational goals. Often, however, the coping strategies are structural in and result in changes in the organizational design. For example, in the 1980s, Eicher Good earth reorganised their operations and the manufacture setup, to cope with increasing competition.

The three plan the company, which were all making tractors earlier, were converted into specialised plants manufacturing tractors, gears, and engines, respectively. In general, the studies on organization environment interface suggest a relationship between the amount of environmental uncertainty and the extent of flexibility in the organizational design.

For example, industries dealing with products related to the fast changing areas of society (e.g., computers, fashion garments, advertising, etc.,) tend to develop more flexible structures to cope with the changing environmental demands. On the other hand, industries in the traditional core sector (e.g., steel, coal, fertilizers, etc.,) exist in a relatively stable environment, and, therefore, are more likely to have an inflexible (and often rigid) organisational design.

Term Paper # 2. Objective/Mission as a Determinant of Organizational Design:

The objective or mission of the organisation is a critical factor which influences its design. In a way, the organisation’s objectives determine which particular segment of the environment it is prepared to interact with. For example, a polyclinic housing specialist doctors may pursue the objective of providing highly personalised total health-care to its clientele.

This objective automatically implies greater amount of attention to the patient (and not just to his symptoms), more coordination and communication among specialists, and greater informality. On the other hand, a hospital following the objective of providing basic health-care to a large population at minimal cost would need to be designed so as to allow a high and quick turnover of patients.

To achieve this, the hospital may introduce formal routines to ensure the operating efficiency. It may also break up the total job into a number of smaller routine jobs (e.g., the specialist doctor may recommend an injection, but it would be administered by the nurse, so that the doctor’s time is saved). A clear statement and understanding of an organisation’s mission or objective has a critical influence on its functioning.

Term Paper # 3. Strategy as a Determinant of Organizational Design:

While the objective mission of the organisation defines what the organization wishes to do, the strategy focuses on the manner in which it will go about accomplishing it. Chandler (1973) defined strategy as the determination of the basic long term goals and objectives of an enterprise, and adoption of courses of action and the allocation of resources necessary for carrying out these goals. Decisions to expand the volume of activities, to set up different plants and offices, to move into new economic functions, or to become diversified along many lines of business involve the definition of new basic goals.

Based on his studies of different organisations, Chandler also concluded that structure follows strategy, that is, the structure or design of an organisation is determined by its choice of strategy. For instance, in 1993, the strategy adopted by Voltas to pull out of trading in favour of manufacturing, led to a restructuring of its thirteen divisions, and the formation of its three strategic business units. Many other studies have also supported Chandler’s contention.

One must note that strategy formulation involves an act of choice regarding how the organisation intends to deal with the environmental opportunities and threats. One obvious way it would adopt would be to develop appropriate structural mechanisms.

For example, in responding to increased competition in the business environment, an organisation has a choice between two strategic courses of action:

(1) It can diversify into different product markets, so as to spread out its risks, or

(2) It can concentrate and protect its market niche, and try to counter competition by decreasing its overall operating costs.

Clearly, the first strategic option will necessitate development of a complex and decentralised structure, while to implement the second option, the organisation will have to create a structure with tighter controls and greater accountability of roles.

Term Paper # 4. Technology as a Determinant of Organizational Design:

Another important influence on organisational design comes from the nature of technology used for transforming the environmental inputs into organisational outputs. Some theorists have defined technology as an intervening variable between the strategy and organisational design.

We cannot jump directly from strategy to management design because we have not yet classified the array of actions that will be necessary to execute the strategy. Thinking of technology helps us to elaborate the work implications of strategy. Sufficient research evidence exists to support the technological imperative hypothesis. The essential logic of these research findings is that since different technologies (mass-production, batch-processing, craft, etc.,) call for different kinds of control systems, they give rise to different structural mechanisms.

There is, however, considerable confusion regarding the definition of the term “technology”. Technology, as a term, is normally used to describe the manufacturing process. But then, what about service organisations (e.g., hospitals, advertising firms, banks, etc.)? Moreover, different researchers have defined technology in different ways, often making it difficult, if not impossible, to integrate the research findings.

One way of getting over this confusion is to understand technology as the process used by the organisation for transforming the inputs into outputs. The input can be raw materials, capital, labour or information, while the output can be a product or a service.

Defined in this manner, technology refers to, in Newman’s words, the “work to be done”. Thus, for example, if the organization is using a customised technology (e.g., as in an advertising agency, a construction firm, or a tailoring shop, etc.), there is a greater need for integration and coordination of the marketing, designing and manufacturing functions.

This would necessitate the development of a loose and flexible matrix structure. On the other hand, an organisation aiming to offer a standardised product or service in large quantity (whether railway transport or cigarettes) would need to standardize its operations, and so, is likely to evolve a formalised structure.

Term Paper # 5. People and Culture as a Determinant of Organizational Design:

It would be too naive to assume that any specific organisational structure (whether it is centralised or decentralised, formalised or flexible, tall or flat, etc.) is an automatic and inevitable consequence of its environment, objectives, strategy, and technology. A more realistic perspective would recognise that any organisational structure is an outcome of a managerial decision-making process.

After all, somebody (a person or a group) has to decide as to, what particular structure is most appropriate for the organisation in a given situation. It is, therefore, but natural that the personal preferences, needs, aspirations and anxieties of these people would play a dominant role in the development of the specific organisational design.

One person, who has a decisive influence on the choice of organisational design is, of course, the CEO (or the departmental/divisional head, in the case of the organisational subunit). Based on their study of a number of “troubled” companies, Kets de Vries and Miller (1987) concluded that the “strategy, organisational structure, and culture will often reflect the personality and fantasies of the top manager.” For example, if the top manager is autocratic by nature, he/she would prefer an organisational arrangement which would allow him/her to have closer control over people and operations.

On the after hand, CEOs predisposed to taking risks would favour the selection of opportunity-based diversification strategies, which may result in less centralised divisional structures.

Term Paper # 6. Age as a Determinant of Organizational Design:

The age of the organization is another factor which makes certain choices of organizational design more appropriate at one time as compared to others. Some organizational theorists have suggested that the criteria of organizational effectiveness changes during the course of its life-cycle.

This is so because as the organization grows and matures, it has to cope with different kinds of environmental demands. Correspondingly, each developmental stage of the organization will favour specific structural mechanisms for coping with these demands.

A young organization, for example, is more likely to be informally structured with lose control mechanisms, since it is still vulnerable to even minor fluctuations in its environment, and must deal with them swiftly. On the other hand, an old well established organization would need to maintain its successful levels of performance, and so, would need to streamline and formalise its structure and systems.

Term Paper # 7. Size as a Determinant of Organizational Design:

While the size of an organization is often related to its age, it is useful to consider it as an independent influence on organizational design. Many organisations, in fact, do not evolve from a small to large size, as is assumed by the life-cycle theorists.

Rather, with huge initial capital investments, they start with the advantage (or disadvantage) of being large. Many studies have identified recognisable relationships between the size and structure of the organization. Blau (1970), for example, found that organisations become more structurally differentiated with increase in size.

Similarly, Pugh et al. (1969) concluded that “an increased scale of operation increases the frequency of recurrent events and the repetition of decisions”.

Such a condition favours standardisation of activities. Another study supported these findings and concluded that “larger organisations are more specialised, have more rules, more- documentation, more extended hierarchies, and a greater decentralisation of decision making further down such hierarchies.” In comparison, the smaller organisations would be more amenable to centralised control, which is exerted through informal contacts.

Implications for Managers:

The preceding discussion highlights the complexities involved in the organizational design process. Designing an effective organization seems to be far from a straightforward linear activity. It appears more like an act of balancing the diverse influences and forces.

Let us briefly consider what implications this discussion holds for practising managers:

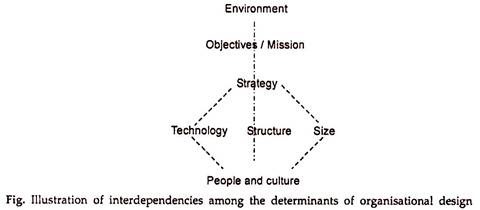

1. One must recognise that the specific design of an organization is not an arbitrary arrangement rather, it emerges out of the influences of many diverse factors. The relationship between the organizational design and its determinants is somewhat complicated by the fact that these various influences on the organizational structure are also interrelated with each other (see Fig.).

A change occurring in any one factor (say, the influencing coalition or the environment) is bound to create pressure for corresponding changes in the others. An effective organisational design (and the managers) must, therefore, be cognizant of such interdependencies and should evolve mechanisms for coping with the pressures arising from change.

2. One needs to appreciate that designing an organisation requires dealing with both the tangible and the intangible aspects. An effective organisation structure takes as much care of the formal business requirements as it focuses on the underlying human processes.

As Newman (1971) Pointed Out:

“Some managers make a change in their formal organisation and assume everything else will fall in place. To be effective …these changes must be incorporated into informal behaviour, and supporting adjustments must be made in other facets of management”.

Thus, for example, implementation of an organisational design incorporating decentralisation of decision-making is not merely a matter of formal documentation of delegation of powers across different hierarchical levels. To be successful it would also require upgradation of decision-making skills across different levels, as well as the development of an organisational climate supportive of such change. During the mid 1980s, due to the liberalisation of economy (and the consequent boom in the consumer durable market), many organisations floundered due to the inconsistencies in their efforts.

Various organisations changed their strategic posture and introduced structural changes to meet the strategic requirements. They failed because these changes were resisted by their own culture. On the other hand, organisations which could effectively deal with changes were those which adapted a more integrated view of these contingencies.

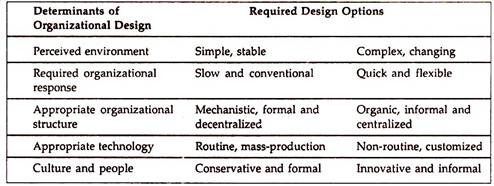

3. Lastly, while the various determinants of organisational design are interrelated, the designing process almost always has to cope with certain constraints. An ideal design would, of course, be one which is totally consistent with the different requirements of the various influences (see Table).

For instance, an ideal situation would be when the strategic requirements call for a flexible decentralised design, which matches with the cultural orientation of the employees, as well as with the influences arising from the nature of required technology. Such a happy situation, however, rarely exists in reality.

One may find oneself, for instance, saddled with a technology which cannot be changed without sacrificing the basic operating efficiencies (e.g., even if the strategy calls for greater autonomy and flexibility, the highly routinised assembly-line still remains the cheapest alternative for mass- producing automobiles). Such mismatches, while posing a major constraint on the logic of the designing process, are also a challenge to the ingenuity and creativity of the manager.